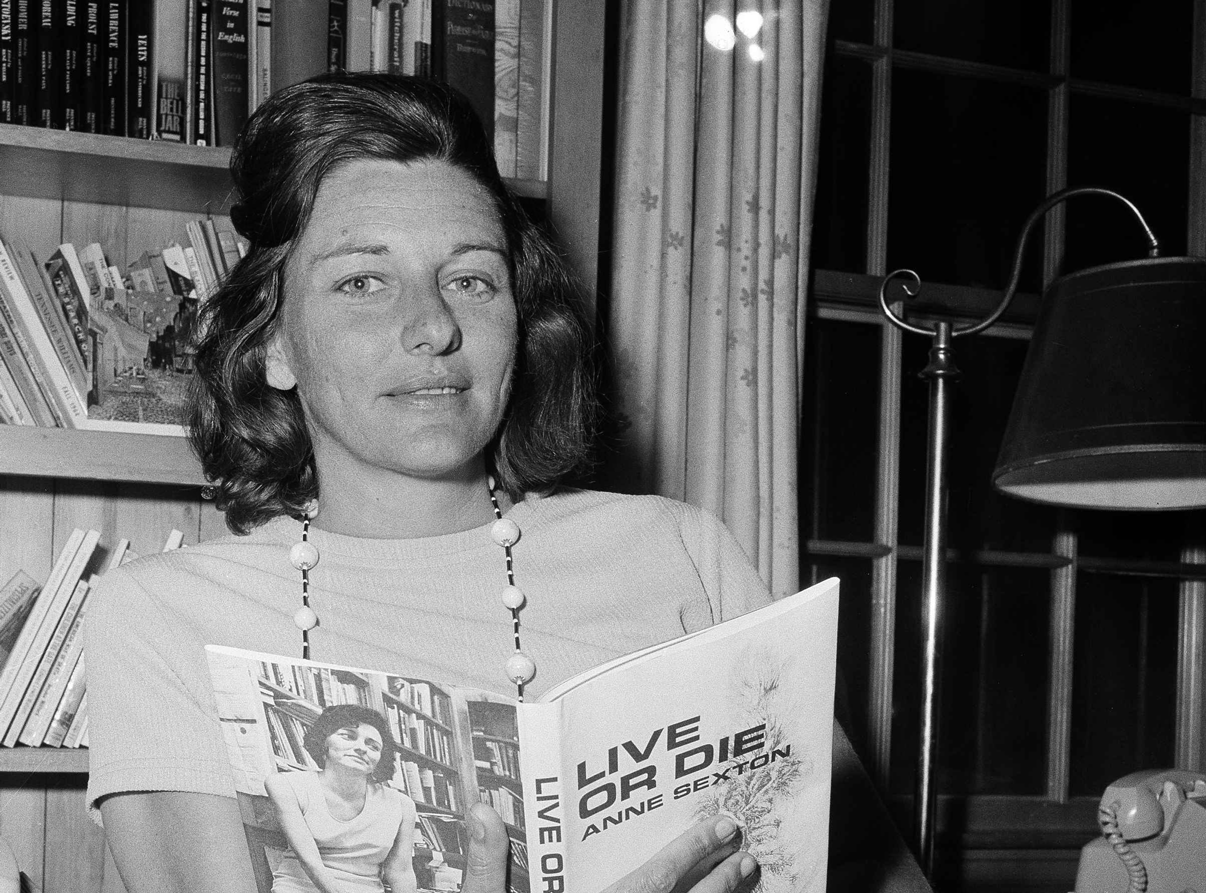

Anne Sexton reading her book of poems “Live or Die,” which won the 1967 Pulitzer Prize for poetry. AP Photo/Bill Chaplis

In early March 1966, poet and public-television presidium Richard O. Moore traveled to the buttoned-up Boston suburb of Weston, Massachusetts, to interview the poet Anne Sexton at the home she shared with her husband, Kayo, and young daughters Linda and Joy. The interview was to be a cinéma vérité–type glimpse into the life of the increasingly famous poète maudite, who just a year later would be awarded the Pulitzer for her second collection, Live or Die. Sexton’s star had been on the rise since the 1960 publication of her first book, To Bedlam and Partway Back, which focused on her psychiatric hospitalization and subsequent return to a degree of normalcy (hence “partway”). Throughout the interview, later aired on San Francisco television station KQED, Sexton presents her home life to the viewer: she reads her work, comforts her daughter, cajoles her camera-shy husband to join her on film, and contemplates death. At one point, she puts on a Chopin record, Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Opus 23. Sexton melts at the opening notes; her demeanor, hitherto coquettish, becomes euphoric. She closes her eyes, arches her neck, and bites her lip as if she’s seducing someone or being seduced. The camera travels down her long, pale arm, which swings just slightly to the beat.

“I’ll tell you what poem I wrote to this,” she says to Moore, smirking. “‘Your Face on the Dog’s Neck.’ Makes no sense, does it? A love poem.” As the music crescendos, the frenetic camera homes in on Sexton’s eyes, which she closes as she exclaims, “Oh, it’s beautiful!” Her joy is overwhelming and carnal and more than a little disturbing. “It’s better than a poem!” she says. “Music beats us.”

A year after she gave that interview to KQED, Sexton tried to bring the forces of music and poetry together with a “chamber rock” outfit dubbed Anne Sexton and Her Kind, named for her ode to deviant women. A single picture included in Diane Middlebrook’s polarizing biography of Sexton shows the group rehearsing in her Weston living room: Anne’s model-long legs are crossed in front of her, flautist Teddy Casher holds his instrument with one hand and conducts with the other, and a few children are facing away from the camera, listening intently.

Internet searches turn up just one recording of the band playing: a boogaloo melody, happy but languidly paced, lightly accompanying “Woman With Girdle,” a poem about the grotesquerie of old age:

over thighs, thick as young pigs,

over knees like saucers,

over calves, polished as leather

What in the poem is an unappealing display becomes, with the addition of the soul-influenced, flute-inflected background, funny, almost self-consciously so. The tone changes from disgusted to celebratory; it’s easy to imagine the fleshy old woman unclipping her garters and rolling down her stockings for a whooping audience, genuinely relishing the attention. The humor was a revelation to someone like me. I had always felt irrepressibly drawn to Sexton’s poetry, but her reputation as an oversharer disturbed me. Was my admiration for her work just a wanton attraction to the bare disclosure of pathologies? I loved the salacious, sure, but was there something more there?

Sexton is a well-known member of a group in poetry commonly known as the “confessional” school, which emerged in the late fifties and early sixties. She was something of an anomaly in poetry, still the arena of scholarly white men, in that she was a housewife with little education. Sylvia Plath, her friend and easiest parallel, was far better positioned for poetic success, as she had attended Smith College and Cambridge; Sexton, by contrast, dropped out of Garland Junior College to get married. “Confessional” is generally considered an irritating and dismissive label. But it articulates what these disparate artists did that was, at the time, so revolutionary. They revealed, more nakedly and honestly than any poets had before them, the intimate and often painful details of their personal lives. For some, like Boston Brahmin Robert Lowell, this expository effort was met with critical acclaim. For others, like Sexton, who wrote—just as Lowell did in some poems—of female sexual desire, mental illness, abortion, and illicit love, the impulse to divulge was often seen as exhibitionistic and dramatic, even campy. This appraisal is less valid when one examines her early work, particularly the pieces collected in Bedlam, All My Pretty Ones, and Live or Die, which are marked by a command of formalism extraordinary in someone who didn’t start writing poetry until she was in her late twenties, after the birth of her two children and her first nervous breakdown. As her career progressed, however, Sexton experimented increasingly with free verse, which yielded mixed results. Over time, the voices of praise quieted, and those who claimed she painted a perverted picture of womanhood grew more vocal. Of all her experimental forays, none is as ignored as her endeavors with music. “Music,” Linda Sexton told me, “was my mother’s muse.”

Listen to Anne Sexton & Her Kind

Seven live performances recorded by Bob Clawson between 1967 and 1971.

- Music Swims Back to Me

- The Addict

- Eighteen Days Without You

- For Johnny Pole on the Forgotten Beach

- The Sun

- From the Garden

- Cripples and Other Stories

The former booking agent, talent wrangler, and erstwhile visionary of Anne Sexton & Her Kind is a tall, deep-voiced man now on the cusp of eighty named Bob Clawson. Clawson’s duties to Her Kind in its heyday were more managerial than musical, though he sometimes moonlighted as a kazoo player when needed. In the decades since the group split up, Clawson has been the sole caretaker of its musical catalogue, live recordings of the twelve performances Her Kind staged during the band’s four years together. Six months prior to our meeting, Clawson sent me a demo CD with six wildly different songs by the band combined into one long track. The rest of the material, he says, is somewhere in his cabinlike abode. Where exactly, he isn’t sure. When a sound engineer who owed him a favor transferred the material from tapes to compact discs, he neglected to label them, and Clawson lost track of the CDs many years ago. They are somewhere in his cluttered basement, he says. “Unless someone stole them.”

A former English teacher and published poet in his own right, Clawson is “wary of being the Anne Sexton guy,” which is exactly what I’m asking him to be, but unfortunately for him, his memory is nearly impeccable. We’re sitting in the small solarium in his Massachusetts home, a shelf of books above his head revealing his eclectic yet sophisticated tastes. Clawson met Sexton when he was a high school English teacher in Weston. One of his colleagues, a friend of Anne and Kayo’s, had glanced over his shoulder one lunch period to see him reading “Menstruation At Forty,” a poem in which Sexton connects her monthly bleeding to the loss of an unformed child and, characteristically, her urge to die (“All this without you— / two days gone in blood.”) He offered to introduce the two, but Clawson wanted Anne to see the papers his students had written about her work first. She was thrilled with the products of such young, vibrant minds, and eventually Clawson paid an evening visit to Sexton’s home to meet the poet whose work he had come to admire greatly. “We met in the bedroom,” Clawson recalled. “Kayo had pneumonia. Anne was getting ready to go to a function—it might have been a reading. She had on a fuchsia satin dress. She has the black hair and she’s all made up and she really looked super sophisticated. She didn’t look to me like the poet I was reading. She looked like she was worldly.”

Soon the young English teacher was stopping by the poet’s house in the evenings on his way home from school. Sexton shared with gusto the pieces that were eventually to be collected in Live or Die and Love Poems. She encouraged Clawson to establish a poet-in-residence at the high school, and together they attended a weeklong seminar in June 1966 hosted by the Teachers and Writers Collaborative, a new nonprofit organization in East Hampton that arranged for professional writers to teach seminars in public schools. Through the collaborative, Sexton and Clawson secured funding to start an experimental English class at a high school just down the road from Weston. In a letter to Herbert Kohl, education advocate and founder of the TWC, Sexton described the duo’s loose, idealistic vision for their classroom: “The teacher (Bob) and the poet (me) will … encourage all student writing as a valuable communication and never give it a mark or hold it up to evaluation that would tend to kill, or block, or ‘clog.’” In September 1967, Clawson and Sexton faced a classroom of teenage students. They had no lesson plan, just an aspiration for a certain ambience. Throughout that academic year, the students wrote poetry and explored experimental forms of writing like graffiti and prayer.

The class standout was Steve Rizzo, a football player whose good looks and dexterity on the field belied a sensitive, artistic personality. He was fascinated by the creative life, personified by these two dashing figures so unlike the rest of the faculty at Wayland High School. “I still remember them strolling across campus,” Rizzo, now in his mid-sixties and a special education teacher at Wayland, tells me. One day, after the class discussed Simon and Garfunkel’s musical adaptation of Edwin Arlington Robinson’s poem “Richard Cory,” Rizzo, a self-taught guitar player, asked to borrow a copy of Sexton’s To Bedlam and Part Way Back. He then set three of Anne’s poems to music, including the poem “Music Swims Back to Me.” (“Music pours over the sense / and in a funny way / music sees more than I. / I mean it remembers better.”)

Rizzo played the pieces for his teachers one day in class, and that afternoon Clawson and Sexton skipped their usual post-work drinks at the Red Coat Grill (Anne favored Wild Turkey bourbon) to assess Rizzo’s performance at the Sexton home. “The airs struck us right off as right on,” Clawson says. Innovation junkies, they were both giddy with excitement. Though neither admitted dreams of music glory, there was an inkling that something unique could grow from Rizzo’s compositions. One thing was for sure: If they put Anne’s poetry to music, they could make her work known to people who wouldn’t ordinarily read poetry. For his part, Clawson says he knew right away that these songs could be the foundation for an official enterprise, so he suggested they play the melodies for a musician friend of his, a classically trained pianist named Bill Davies. He was impressed. Rizzo, Davies, and Clawson reached a consensus without so much as a discussion: they would form a band, with Anne as their front-woman. Sexton, always game for a challenge, was gung ho. Rizzo was excited to be a part of the venture. “It was an education in a different kind of way,” he told me, “even unrelated to just the poetry and the music itself—being a part of creative people’s lives.”

Rounded out by flautist Teddy Casher, a working musician today, even in his mid-seventies, and a rotating cast of drummers and bass players, the band riffed on Sexton’s poems with bebop and post-bop jazz and spiritual hymns, along with styles from the aural landscape of the late Sixties—psychedelia, protest folk music, Eastern strings. The end of “The Addict” incorporated a lullaby-esque tune; for “The Sun,” they went with what Rizzo calls a “spacey” tune. They were rigorous about the music being as well realized as the poems, not just improvisational “noodling,” as Clawson puts it. Anne didn’t sing but read the selected poem over the music. Because of the accompaniment, she couldn’t fall back on the routine cadence she used in her readings; instead, she learned to time her throaty utterances to the beat of the music, aided by Clawson’s helpful coaching.

With each new composition, the group actively sought to incorporate genres of music they hadn’t used before. “We didn’t have country music,” Clawson recalled. “It occurred to me that the poem ‘Cripples and Other Stories’ had the right beat for country, and we started doing it, and we were rolling on the floor laughing. We knew we were going to knock an audience sideways.” They rejigged the poem to make an early quatrain into a refrain: “Each time I give lectures / or gather in the grants / you send me off to boarding school / in training pants.” The honky-tonk song pleased the guys to no end, but they were unsure that Sexton would like it—the poem, after all, was a rather serious meditation on deformity, both physical and emotional. (“The surgeons shook their heads. / They really didn’t know — / Would the cripple inside of me / be a cripple that would show?”) There was a fine line between lighthearted jesting and mean-spirited mockery.

“We brought it out at a Sunday rehearsal and said we wanted to try something,” Clawson remembers, “and Anne said, ‘Over my dead body! No. No way.’” Clawson convinced Sexton by playing her “Alabama Song” from Brecht and Weill’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. “It’s got these dark, dark lyrics but the melody is so schmaltzy. And she said, ‘Alright, we’ll give it a try.’ She was still very cautious. We did it at the close of the first half at the next concert we had, and Anne began the reading, just the reading, with nothing, no music. And as she read, the music begins to pick up behind it just a piece at a time. And then it starts to become slightly integrated, and then a little more integrated. And then you start to think, ‘She might burst into song or something!’ But she calls me out of the audience, and says, ‘Bobby!’ and I rush up on the stage, and there’s Teddy coming over to the microphone, and I’ve got a kazoo and Teddy’s got a saxophone and we take off singing it and doing the bridges with the saxophone and the kazoo. And the audience went bananas.”

From 1967 until their disbanding in 1971, the group wrote and performed. They played at a fundraiser for Eugene McCarthy, at bars where the air was thick with marijuana smoke, in college quads, on radio shows, and at the New England Conservatory of Music’s Jordan Hall, in front of a thousand rapt listeners. The men wore turtlenecks and jackets. (“We weren’t Kiss,” Clawson says.) Anne wore long dresses: she had two favorites, a red one and a black-and-white one. “She moved discreetly,” Clawson says. “She had those long arms and long fingers. Her movement was lovely . . . it wasn’t frenzied . . . she might wink at the audience. She was really engaging.”

Anne Sexton the performer stands in some contrast to Anne Sexton the poet. Though both Linda Sexton and Bob Clawson claim she had no sense of rhythm and often fell into a kind predetermined modulation better suited for readings than musical performances, her voice on the recordings is lilting and measured, rising and softening in accordance with the band. Listening to a performance of “Protestant Easter,” a hilarious poem that digs at New England Calvinism from the point of view of a child (“After that they pounded nails into his hands / After that, well, after that / everyone wore hats”), I begin to envision her covered in sweat, down on her knees in front of a congregation, shouting “Praise Jesus!” as the organ trills away behind her. It becomes clear to me that I cannot separate the less comfortable aspects of Sexton and her work from the parts that are more easily accessible and more widely lauded. It was her unusual daring—can you imagine Plath doing a doo-wop version of “Ariel?”—that fueled Sexton’s work. I couldn’t take only the fine formal verse and discard the later, sloppier, more desperate writings. I couldn’t discard her failed experiments with prose and cling to only what was deemed Pulitzer-worthy.

Sexton’s flair for performance wasn’t universally appreciated, another reason why music was in some ways a friendlier environment for her than the stuffy world of academia. In the poetry world, in fact, many found her style off-putting—gauche, sloppy, unrefined. She famously drew ire when she blew the crowd a kiss following her time at the Poetry International Festival in London in 1967. Those close to her attribute her theatrical overcompensation to her intense stage fright and the drinking she did to calm her nerves.

“She did drink before performances. I could not force her not to,” said Clawson. “I think it’s really detrimental. In performance, you really have to have all your antennae attuned. But she said she couldn’t do it without it. I’d be furious after a concert because it was so good live, and then you’d listen to the tapes and you’d think, ‘Ah, she blew that one.’” The recording equipment would pick up things like slurred speech and missteps in timing, which were easy to ignore amidst the heady atmosphere of the show. The products, therefore, were useless. Casher and Clawson both single out recording as the hurdle that ultimately couldn’t be jumped. It started to feel like making an effort might not be worth it if Anne was always going to be sloshed. Clawson didn’t even bother to record what would be their last show, at Emmanuel and Wheaton Colleges outside Boston, because he assumed she’d stumble through it. As it turned out, she vomited up her cocktails and whiskey, and as a result gave a more sober, seamless performance than she had in months.

After that things further deteriorated, both for Sexton personally and the group. The band was offered a slot at the Newport Jazz Festival, which would have certainly put them on the map, but Sexton refused because they couldn’t pay enough. Then she reneged on a gig at Holy Cross, saying there was a priest affiliated with the school who had disparaged her work. Perhaps, as many critics have suggested, her hunger for validation—in the form of applause, accolades, and other hallmarks of fame—began to grow deeper the more she tried to satiate it, and, dispirited, she unconsciously turned her back on poetry and performance, the only things that had ever made her happy.

“The gift that she had,” Clawson muses, “I think it sustained her as long as she lived. The performance she knew was necessary to achieve what she wanted, stardom in poetry … I think if there had been records of Anne Sexton & Her Kind playing at the time she was alive, she would have lived longer.” But it wasn’t to be—Sexton committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning at 45. “She needed again and again, stuff like that,” said Clawson. “She needed it for self-affirmation, so she put herself through that. She didn’t lead a life that any of us would envy. I mean, you might envy it from the point of view of her profession, and say, ‘Wow, she was quite a poet,’ but it was not an enviable life.”

But then Clawson brightens for a moment, remembering one particularly joyful moment during a performance. “Anne always said, ‘I cannot sing. I can only sing one song, “Cigarettes and Whisky and Wild, Wild Women.”’ Except—” Clawson hesitates, looking for the right word. “A little epiphany or a miracle, whatever you want to call it. About the third or the fourth time we’re doing this in concert, I realize Anne has come up right behind me and she’s singing! She’s singing. And you can hear that in the tape. If you listen carefully, you can hear Anne singing, and she’s having such a good time.”