It was in 1988 that I moved to the bedraggled neighborhood of Hyde Park in order to study American history at the University of Chicago. I left the city ten years ago. And though I was raised in the suburbs of Kansas City and live today in the suburbs of Washington, it is Chicago that made me who I am.

During my time as a graduate student, a mildly famous memorandum, written by a classics professor in the 1960s, was passed from hand to hand. It bemoaned the sheer awfulness of life at the university, “located in an unpleasant city, in a nasty climate, a thousand miles from anywhere.” I remember being surprised to read this, and being similarly surprised every time somebody referred to Chicago’s brute ugliness. Looking back all these years later, however, I see that it was true.

Once you got away from the neighborhoods near Lake Michigan, the city was ugly. It was “unpleasant.” I’ll go further than that: it was a menacing landscape of litter and rust and concrete and dereliction and vacancy and apartment complexes that looked like they had been designed to crush their inhabitants’ souls. On the South Side, where I lived, the air often stank of whatever industrial operation was taking place down in Indiana. And after a day or so on the ground in Chicago, the snow would turn gray.

I loved the place. I loved the decay, the vacant lots, the dirty snow and the tawdry taverns and the wooden stairs, covered with peeling paint, that were attached to the back of virtually every three-flat in the city. Maybe love is always what happens when you take up residence in your first real metropolis. Kansas City, where I grew up, didn’t count; its urban character had been done in by decades of white flight and enervating sprawl. Chicago had bars, bands, bookstores. A great university. A real organic downtown, not a Potemkin business district propped up by a desperate chamber of commerce.

What Chicago didn’t have back then was any real presence in the nation’s visual media, aside from glimpses in gangster movies. The only parts of the city that penetrated the collective imagination were the prosperous and all-white North Shore suburbs, the setting for countless teen-angst movies of the 1980s. The rest of it was essentially terra incognita. I was aware, of course, that Chicago had once been a celebrated place. In the late nineteenth century, it had stacked wheat and butchered hogs and gone from hamlet to Midwestern colossus almost overnight. The residue of that mighty past persisted in the neighborhood where I lived: rotting monuments, formerly grand buildings, overgrown parks that had been laid out by illustrious names.

But in 1988, Chicago had yet to enter the postmodern world; hell, it hadn’t even gotten finished with de-industrialization yet. Here and there, steel mills still dotted the South Side. Freight trains clattered slowly over crumbling viaducts, the walkways underneath decorated with disintegrating social-realist murals. Enlightened New Economy sociologists of the future would have no difficulty diagnosing this condition: Chicago in those days had no brand.

Actually, there was one area in which Chicago had established a brand: that unauthorized form of advertising known as literature. I duly armed myself with a shelf of the classics, including Sister Carrie, The Pit, Studs Lonigan, Native Son, The Man with the Golden Arm, and Division Street: America.

Most of these books, as Thomas Geoghegan pointed out in an influential 1985 essay, were concerned with working-class people. And this was important for understanding the exact form of obsolescence that hovered over the city. The ruins that surrounded you on the South Side were the relics of a civilization that had built great things, that had made the world go. “Even the sublime in Chicago has a 1935-proletarian taint,” Geoghegan noted — and for me, this nailed it. Chicago was my Art Deco Rome, and as I rode the creaking Green Line trains or dropped off bags of heavy literary magazines in the dark caverns of the old main post office, I would imagine myself wandering around the Baths of Caracalla.

Geoghegan also argued that Chicago was “the last great American city not ruined by yuppies.” This sounds pretty outrageous, given Chicago’s current status as home to the largest concentration of hipsters outside Brooklyn. But it certainly felt true in the late Eighties.

What the city taught you then, and to some extent will teach you now, was a certain sort of harsh empiricism. It was a place that set your bullshit detector on hair trigger, permanently; it allowed you to see right through the fatuity of the moment. The healthiness of this is, I think, impossible to deny, especially when you look back over the long parade of delusions that have in the intervening years gripped the nation’s leadership class, eroding our politics, journalism, economy, and institutions of higher ed.

That class and their foolish ideas could all go straight to hell. That was my attitude in those days, and as I picked up my pencil and went off to the culture wars, I believed it was an attitude that Chicago itself, the last great beacon of bullshit-resistant probity, had encouraged in me.

Or so I told myself. In truth, the city of Chicago has been as big a sucker for bad, trendy ideas as any other place, privatizing highways and parking meters, encouraging gentrification, badgering the local teachers’ union, and so on. But let us put all that aside for the time being, and return to my romantic fog of more than two decades ago.

My friends and I moved into those stately, decrepit old buildings in which so many university students live — none of us could afford the modern, windowless pillboxes from the urban-renewal days. We built up a wall of punk-rock noise around ourselves, taking to the airwaves on the university’s radio station to play the obscure and abrasive and massively alienated “independent” music of that period, which we believed to be part of an important artistic awakening. (On certain days, I still feel that way.)

In 1992, a bunch of us moved into new quarters: half of a battered Queen Anne mansion in Kenwood, a neighborhood filled with battered mansions. Some considered it a risky location, and indeed on one occasion a burglar swiped my VCR, but the place also had the advantage of standing just a block away from the peculiar old storefront where we bought dreadful cheap beer by the gallon. With our thrift-shop furniture and our clothes purchased at the rummage sales of Winnetka and Lake Forest, we settled into that Schloss like the impoverished heirs to some once great fortune, and got busy.

We had already launched The Baffler, conceived as a campaign of mockery and derision against the modern corporate world. In its pages and elsewhere, we wrote about music, about politics, about strikes — particularly the big ones then unfolding at several industrial concerns in central Illinois. But the subject of almost obsessive interest for us in those days was the relationship between adversarial art movements and the broader commercial culture. It was, of course, a debate with a lot of history to it, but as we watched the national media circle hungrily around the subculture that we ourselves inhabited, it all seemed sharp and new and full of treachery.

It occurred to me, living in that great old house in Kenwood, that all the hostilities of the culture wars were a kind of fraud. Behind the endless TV battle of hip and square, the conflict between strict parent and pleasure-loving teen, the back-and-forth of slut-shaming and prude-shocking, lay the prerogatives of capitalism. Our many uprisings against Victorian moralism hadn’t challenged the money power in the least. These insurgencies not only missed the point — that the problem was capitalism, not conformity — but actually stoked the engines of fashion. To put it another way: my own generation’s dissent was being commodified right before my eyes, and all I could do was look on with distaste and desperation.

Well, we know how all that worked out. A few years after the discovery of “alternative” culture, Chicago became a kind of second Seattle. All the bands got major-label record deals, and a whirlwind of gentrification swept through certain neighborhoods on the North Side. And somewhere along the way, I lost interest in the whole phenomenon. Deriding the yuppies who colonized the trendy neighborhoods was just another way of missing the larger point. There were big forces at work in Chicago: the steel mills were almost gone, and soon the public-housing projects would come down as well. The entire city — the entire nation — was being reconceived along new lines. The poor were to be expelled, and room was to be made for swanky new corporate headquarters and an enlarged financial sector and a green zone wherein cosmopolitan citizens with cash and taste could safely play.

Walking the streets of Hyde Park on a cloudless day in late September, ten years after leaving for good, I am impressed by how serene and grown-up and even beautiful it appears, this place that was once the scene of such fiery intellectual argument. I notice, probably for the first time ever, the clinging ivy and gracious details of the Tudor-style town houses across the street from the apartment where I watched the Gulf War on CNN.

The university itself, which appeared so shabby when I walked its halls as a nervous graduate student, looks pretty good. In the old days, my friends and I used to dismiss its Gothic architecture as so much pretentious fantasy — the thing was built at the turn of the twentieth century, after all, not under the Plantagenets. But today, thanks to what appears to be an assiduous landscaping and power-washing campaign, the U of C fantasy looks healthy, even authentic.

The school is on a construction spree, financed largely by bond issues that have ballooned the institution’s debt load like that of any world-class corporation. They’ve built an enormous new Center for Biomedical Discovery and an arts facility in an eleven-story tower. They’re working on a new home for the economics department fashioned (appropriately enough) from an old theological seminary. And in the surrounding neighborhood, the bulldozers have been just as busy: there’s a new Hyatt, a brace of improbably upmarket stores, and signage announcing a new office-and-apartment complex, whose design suggests an homage to the UPC bar code.

It is tempting to lay at least some of this at the feet of the President of the United States. Ten years ago, Barack Obama was a state senator whom you could easily meet at Hyde Park house parties; today, the chair where he used to get his hair cut is preserved in a vitrine in the neighborhood barbershop. On 53rd Street, there is a monument marking the spot of his first kiss with Michelle, in 1989. And there’s no tonic for a neighborhood quite as potent as having a chunk of it patrolled by the Secret Service — as it happens, a chunk of South Greenwood Avenue a mere three blocks from where I once lived.

The vacant lot next door to President Obama’s house, a notorious bit of real estate once owned by the Illinois corruptionist Tony Rezko, is lined with concrete barriers and those fast-growing evergreens people use to screen out undesirable views. In fact, steel security fences seem to have gone up all over the neighborhood, and now surround the Queen Anne pile where my friends and I worked on The Baffler. Through the fencing and a row of those privacy trees, you can see that the house has been nicely restored. And although I keep expecting to hear the throbbing minor chords of Silkworm or the Laughing Hyenas issuing from within, everything is still.

Maybe that’s because, in the years since then, the world has been turned right side up: the house has been recalled to the life and the purpose for which it was created. It seems the present owner of the Schloss where my friends and I pantomimed the rich and plotted our adventures in criticism is a prominent figure in the wealth-management industry. He has taken up this vocation out of personal experience, having inherited a sizable share of the Carnation Company (evaporated milk, pet food, nondairy creamers) before it was sold to Nestlé in 1985. “We wealth owners owe it to ourselves to learn, to protect our own interests, and to hold our advisers accountable,” he has declared. He has also written a book called Wealth: Grow It, Protect It, Spend It, and Share It, which informs us that the author “teaches the Private Wealth Management program, exclusively for wealth owners, at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.”

Reading over the foregoing, I feel certain that my former, Chicago-minded self would have chided the sentimentality of that penultimate paragraph. What if I had heard some familiar notes coming from within the mansion? How shocking would it be to discover that some wealth-management guru was also a fan of punk rock? Or that some indie rocker had gone into the wealth-management biz, building a career on that transition, constantly alluding to his or her bold, iconoclastic past? Nothing all that odd in either case, the old me would have insisted.

And he would have been right. “Rock ’n’ roll is the health of the state,” I wrote in one of my darker moods back then, riffing on a famous quote from my hero Randolph Bourne; what I meant was that the machinery of consumerism depended on the allure of nonconformity. Today, obviously, it’s gone much further than that. The Internet itself is one great tribute to the countercultural idea. And the logic extends into the world of luxury goods. Consider the matter of experimental gastronomy, a field in which Chicago is today more advanced than nearly all other American cities.

The city already had plenty of tony eateries back in the 1990s. There was Charlie Trotter’s, for example, and Chez Paul, a French restaurant that inspired some hilarious bits of nose-tweaking in both The Blues Brothers and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. But the real gastronomic explosion took place after I moved away. The city’s perennially escalating restaurant war turned into a battle of foam and fried residue and gently farting bags of lavender vapor and a veritable Sanitary Canal of infusions and extrusions and emulsions and reductions.

By now, this has gone far beyond the familiar and played-out snobbery of regionalism. It is a competition between chemists constantly pushing their advanced knowledge, their esoteric tools, their pointless specialization. How did we ever get by without hibiscus spheres filled with tomato water, or crab in vinegar gel garnished with micro lemongrass, saffron threads, and eight grains of black lava salt? No less important is the doctrine of physical inaccessibility, which makes certain restaurants as selective as Ivy League colleges. There is a vogue for underground eateries, for pop-up meals prepared by a chef in a private apartment or an art space. Other establishments reportedly screen potential diners and invite only a chosen few to darken their epicurean doorsteps.

The one that really captured my imagination was a bar called The Aviary. You must email your request for a reservation and then be selected. I wasn’t, during the course of my last trip to Chicago, and so it was not my privilege to experience the bar’s ten-course cocktail tasting or appreciate the technical expertise of its ice chef. In an online video about The Aviary’s “ice program,” however, we learn what we need to know: that the ice itself may be made from distilled sorrel juice, molded in different ways, whittled by hand, or carved by chain saw. Ice-chipping is “a new art form,” we are told, and aspiring masters “will apprentice for years before they will ever make a cocktail, simply hand-carving ice.”

Needless to say, the gastrosphere exists to flatter and service the rich. It is also unremittingly hip. Avant-garde theater groups perform plays about microbrews. There is Baconfest, an annual event guided by a semi-ironic manifesto. And consider Lollapalooza, the legendary alt-rock festival that gave up touring and is now held every year in (of course) Chicago. Not too long ago, festival organizers recruited the celebrated Chicago restaurateur Graham Elliot Bowles to serve as “culinary director.” To feed the moshing masses, he put together offerings such as lobster corn dogs and truffle-Parmesan popcorn.

But it was my meal last month at Longman & Eagle, a take on the old Chicago neighborhood tavern, that finally made me want to scream. I was sitting there, making my way through a winking parody of the Chicago-style hot dog: an assembly of sliced-up steak, “hot dog bun puree,” “housemade pickles,” a mustard-flavored wafer, and so on.* (Later I would have Old Style ice cream, Old Style being the quintessential blue-collar Chicago beer.) At some point, I noticed that the speakers were playing one of the favorite songs of my youth, “Brickfield Nights,” by the Boys, a fairly obscure punk band from the late 1970s. Next came a song by Wire, from their Pink Flag album. Then “Sonic Reducer,” by the Dead Boys, and “Remote Control,” by the Clash.

Every one of these songs hit home — this was the music I once thought would change the world. Now it was a sound track for the fussy morass of late capitalism. It was a signifier that assured you the neighborhood was safe, that you were in the green zone, among correctly educated people, enjoying real culinary luxury and not some cheap knockoff. That’s what the Clash was good for, in this corner of the U.S.A. circa 2013. The world was burning, but here we were having a happy riot of our own.

There is a microdebate in cyberland about whether the gastronomy thing is the heir to the indie-rock thing I once conceived to be so meaningful. Just about everyone who takes the time to comment on the idea (like the people at the Food Is the New Rock blog) agrees that it is. But it would be more accurate to say that it has inherited everything that was irritating about indie rock — the preciousness, the hero worship, the fruitless pursuit of the authentic. Worse: what were subdued notes of privilege and snobbery in the music are these days out in the open, the power chords that carry the whole thing along. We are talking, after all, about food for the rich — the only people who can afford those $200 VIP tickets to Baconfest.

We have come a long way from the city whose marginal humans were chronicled by Nelson Algren and Richard Wright. The new Chicago, this dynamic commercial hub, may ironically deconstruct the coarse food those authors’ beloved fuckups used to eat — but it moves further away from them every day. And beyond the perimeter of the nicer neighborhoods, things are not so dainty or digestible. Chicago now leads the nation in homicides; just before my last visit, the crime wave crested in a South Side park, where a gunman unloaded his semiautomatic rifle into a group of kids playing basketball, hitting thirteen of them. Similar acts were occurring almost daily.

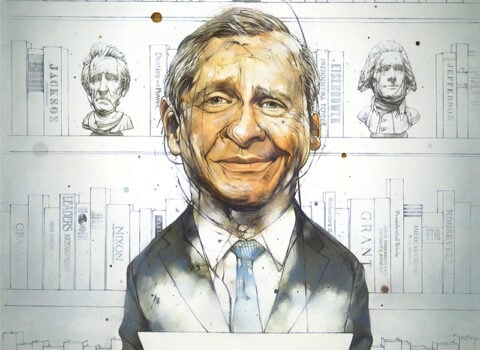

And presiding over it all is Mayor Rahm Emanuel, the legendary political tough guy who makes his iron-willed, six-term predecessor, Richard M. Daley, resemble a cowering child. I want to like Emanuel. After all, he is possessed of “as much determination, will, and chutzpah as anyone alive,” writes the Chicago journalist Ben Joravsky, yet “he uses it all on wimpy policies that largely preserve the status quo.”

This is an understatement. Emanuel has had a hand in every betrayal of the Democratic Party’s working-class base since the Clinton years, from NAFTA to the Wall Street bailout to Obamacare. The goal of his brawling is never to preserve the status quo: it is to hustle the nation into a market-based, big-bank Arcadia that differs from the Republican utopia only in that it has bike lanes and gay marriage. Chicago, then, must be turned into what its mayor endlessly calls a “global city.” In pursuit of this fanciful designation, he has privatized and outsourced, closed traditional public schools and celebrated dubious charter undertakings, warred on unions, and subsidized private business. In Chicago’s strangely tidy streets, the rest of the nation can get a glimpse of the future: a city that works — for a few.