Last fall, the Man Booker Prize, the premier award for fiction in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth, announced that it was coming to America. Presumably Edward St. Aubyn had already finished his fictional send-up of the Booker, lost for words (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26), or else he would have included a ten-gallon tale in full Texas drawl on his short list for the made-up Elysian Prize. Get it? Elysian? Literature is dead.

The Elysian is funded by a “highly innovative but controversial agricultural company” of the same name, whose mandates go beyond genetically modified crops into “weaponized” agents that cause “any vegetation on the ground to burst immediately into flame, forcing enemy soldiers into open country where they could be destroyed by more conventional means.” A prize is good P.R. in real life too, where the Man Group manages $52 billion a year and bestows $80,000 on the Booker. Of course, as the Austrian irritant Thomas Bernhard knew, starving artists can’t be choosy. As he wrote in My Prizes, still the best take on renown shamefully accepted, “No one reproaches a beggar on the street for taking money from people without asking where they got the money they’re giving him.”

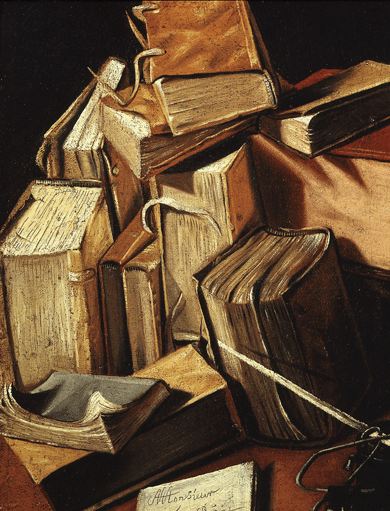

Still Life of Books (detail), by Charles Emmanuel Bizet d’Annonay © Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York City.

St. Aubyn’s committee is dysfunctional when it isn’t outright corrupt. The chair is a cheat of an MP, and the other members aren’t any prizes (ahem): a “media personality” obsessed with “relevance”; an English professor whom nobody, especially her own daughter, can stand; somebody’s ex-lover; and that same somebody’s godson, an actor too busy with rehearsals to get himself to the meetings. They’re fighting over an Irvine Welsh rip-off (wot u starin at), a “literary” bildungsroman (The Frozen Torrent), some nonsense about Scotland (The Greasy Pole), historical fiction about the life of Shakespeare (All the World’s a Stage), and a collection of Indian recipes that’s been mistakenly labeled an experimental novel (The Palace Cookbook). That last one should raise an eyebrow or two. Yes, he went there.

St. Aubyn is known for going there, though thus far the target has been closer to home. In his Patrick Melrose quintet, victim became executioner as St. Aubyn fictionalized his upbringing at the hands of a sadistic, child-raping father and an emotionally absent mother, his years of drink and drug, and his own marriage, divorce, and turn at fatherhood. If you can bear the abuse, his skewering of the vanity and habits of his parents’ milieu is sheer nasty pleasure. Lost for Words abandons the comedy of manners (and sophistication, both subject and style) in favor of another British tradition, the broad satire. Character here is shorthand and stock-type. The Frenchman is the semiotics-obsessed author of Qu’est-ce la Banalité? The Indian prince — the cookbook was written by his aunt — is a madman and a clown. The female writer is a lonely nymphomaniac whose brilliant novel never made it to the judges because her publisher, whom she was bedding (he thought it was love!), asked his assistant to send it, and the assistant sent the cookbook by mistake. When the MP takes the podium to announce the winner, he has no idea what’s in the envelope — the committee was trading votes backstage until the very last minute.

Occasionally a surprise issues from an unexpected corner, as when Mr. Wo, the cheerful chairman of Shanghai Global Assets, Elysian’s parent company, opens his mouth. “If an artist is good, nobody else can do what he or she does and therefore all comparisons are incoherent,” the avant-garde Wo says.

Only the mediocre, pushing forward a commonplace view of life in a commonplace language, can really be compared, but my wife thinks that “least mediocre of the mediocre” is a discouraging title for a prize.

Finding this funny requires holding a certain view of the kind of people who run companies with names like Shanghai Global Assets, but satire does usually depend, somewhat, on stereotype.

Lost for Words has special ire for “personal taste,” that sacred cow of entertainment’s consumer-driven content farms. But its one argument for what might pass as a standard (or at least expectation) for literature is undeniably personal. Vanessa, the much-maligned English professor, catches herself thinking about King Lear in reference to some ongoing family strife.

And then she found herself wondering why any book should win this fucking prize she had become involved with unless it had a chance of doing what had just happened: coming back to a person when she wanted to cry but couldn’t, or wanted to think but couldn’t think clearly, or wanted to laugh but saw no reason to.

Not that she’ll have her way in the end. The MP puts it like this:

Vanessa had taken on the role of a doomed backbencher, making speeches to an empty chamber about values that simply had no place in the modern world. Frankly, he felt rather sorry for her.

The waning power of the novel is surely less related to “multiculturalism” and cultural studies, St. Aubyn’s too-easy targets, than to technological change and television. But there is no need for pity. The happy few will muddle on, same as it ever was. Literature is one arena in which history is not written by the prizewinners.

Evie Wyld’s second novel, all the birds, singing (Pantheon, $24.95), is the kind of prize bait Vanessa would love, with poetic sentences of sharp, precise descriptions, alternating chapters moving forward and backward in time, and a damaged narrator who finds something resembling emotional rescue. Wyld comes with a pedigree. Her first novel, After the Fire, a Still Small Voice, won two awards, and Granta named her one of their Best of Young British Novelists 2013. For better and worse this kind of ranking and credentialing is how (the few) readers of contemporary fiction choose what to buy, and Wyld, at least, is deserving of recognition. All the Birds, Singing is a serious book, and it takes itself seriously. It is self-consciously wrought and, like much prize fiction, has a curiously out-of-time quality that betrays no worries about the purpose or utility of novel-writing in the twenty-first century. Its backwoods setting complements its style of literary survivalism.

The story opens on Jake, a young Australian woman living as a sheep farmer on a rainy, lonely island far from home, stalked by birds and men. She’s not doing any slaughtering, but members of her flock keep turning up dead.

The story opens on Jake, a young Australian woman living as a sheep farmer on a rainy, lonely island far from home, stalked by birds and men. She’s not doing any slaughtering, but members of her flock keep turning up dead.

Another sheep, mangled and bled out, her innards not yet crusting and the vapors rising from her like a steamed pudding. Crows, their beaks shining, strutting and rasping, and when I waved my stick they flew to the trees and watched, flaring out their wings, singing, if you could call it that.

Jake has a hard time communicating with people, but she’s intuitive with animals. She doesn’t wear a back strap when she shears sheep, because she’s learned how to hold them close and keep them calm so it’s like “taking the skin off an orange.”

The present-day plot is quiet and holds violence at arm’s length while the flashbacks are increasingly gruesome, delivering compounding traumas: prostitution, kidnapping, rape, arson. Someone loses his hand in a horrible shearing accident; many references are made to the scars on Jake’s back, which aren’t explained until the last dozen pages. It turns out Jake isn’t quite the victim she’s seemed, or at least she’s a different kind of victim; the narrative aims for suspense, but the reveal, when it comes, feels overdue. The real pleasure in All the Birds, Singing is its brutal descriptions of the body (a swollen hand is likened to a “meat fist”) and its gorgeously vivid landscapes — ripe material for a Jane Campion movie or miniseries.

At first Jake blames local teens for her sheep’s deaths, though as time passes she comes to believe that there is an unknown animal on the land. Wyld never resolves the identity of the creature, nor does she give any indication what will happen to Jake, or to Lloyd, a stranger who has shown up with an offer of friendship. (The novel prefers evocation to explanation, and never even makes plain where Jake is living.) The last note is pretty but falsely profound, with the two holding hands — maybe predators or maybe prey — as “something crunched in the undergrowth.”

Prizewinners like Evie Wyld can get book deals because publishing is kept afloat with celebrity memoirs, political biographies, and powerhouses like James Patterson, who employ armies of assistants to churn out formulaic bestsellers. Why is factory-foreman writing disparaged by cultural elites while factory art — by Damien Hirst, Maurizio Cattelan, or Takashi Murakami — is deemed worth paying millions for? Perhaps rich people would like James Patterson books if they cost more.

According to the economist Don Thompson’s the supermodel and the brillo box (Palgrave Macmillan, $27), the global art market in 2012 generated $42 billion in sales. (That’s about the GDP of Ethiopia or Yemen.) Harder to wrap your head around is the “value” of the individual works. One of the members of the Mugrabi family, which owns at least 800 Warhols (the largest collection outside the Warhol Museum), put it this way: “$8,000 a work is not that interesting. At $80,000 it becomes more interesting. At $800,000 it is the talk of the town.”

The Supermodel and the Brillo Box is a reworking of Thompson’s first book, The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, and one ought to read one or the other but not both. Caveat emptor: Thompson is no writer’s writer. Too long by a third and needlessly repetitive, The Supermodel lacks clarity about its target audience. (It’s best to skip around rather than to read straight through.) But being that Thompson is an economist, he is excellent at explaining the financial transactions that generated that $42 billion, like commissions, guarantees, and irrevocable bids. The art world is more than a confidence game — it’s an unregulated money market in which galleries and auction houses provide loans to consignors and collectors. The “free” market operates here much as it does elsewhere, by being propped up and framed. Auction prices are routinely bid up by interested collectors like the Mugrabis and dealers like Larry Gagosian, who don’t want the value of their holdings to decline. So much is concentrated in so few hands that the threat of a dump must be, and is, continually warded off.

But who really cares how bankers spend their money? Except this: when someone locks up a Warhol in a warehouse in New Jersey, no one else can then see that Warhol. The real problem with the art market — and Thompson addresses this only passingly and dispassionately — is what it does to public access. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, patrons hoarded paintings but also founded museums; now the only person doing that is Alice Walton. Institutions outside the United Arab Emirates can’t afford to compete with the ultrawealthy to build collections, and the art they can show is selected, at least in part, because a dealer or collector will underwrite it. When The Scream was sold at Sotheby’s in May 2012, the only public institutions considered potential buyers were the Getty in Los Angeles and museums in Qatar and Abu Dhabi; the painting ultimately sold for $119.9 million to Leon Black of Apollo Global Management, number eighty-five on the Forbes 400. The ever-rising cost of museum admission is also an indirect result of this need to compete with private collectors’ extraordinary purchasing power. Cultural treasures have become luxury goods.

There is justice, I suppose, in knowing that the captains of industry who sustain this house of cards deserve at least some of the work they get: Hirst, Cattelan, Murakami, and Jeff Koons, all of whom are featured in The Supermodel and whose work routinely sells for stupid amounts of money, are adolescent pranksters responsible for some of the least interesting art ever made. This is an aesthetic judgment, which Thompson can’t make, because he holds the economist’s belief that works of art are fundamentally about their price. He’s right insofar as it is impossible to make a statement about contemporary art that doesn’t take some account of the price tag. But he’s wrong that this is inevitable, and that any kind of neutral mechanism assigns such value: his list of the “top” twenty contemporary artists, achieved by “consensus” rankings of dealers, auction specialists, and art advisers, consists of Caucasian and Chinese men vying for dominance, and entirely excludes women. Thompson analyzes artwork in relation to its “backstory,” a needless term that amounts to cocktail-party chatter — anecdotes surrounding the work’s history or provenance that travel easily, in the manner of reputation. “Backstory” is ultimately the logic of the market itself, which will do anything to avoid a discussion of “meaning.” But there I go again, making speeches from the back bench.