Discussed in this essay:

The Long Voyage: Selected Letters of Malcolm Cowley, 1915–1987, edited by Hans Bak. Harvard University Press. 848 pages. $39.95.

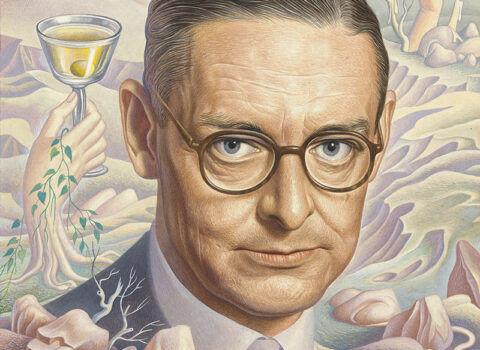

Malcolm Cowley made his name as an ancillary member of the Lost Generation in Montparnasse and Greenwich Village, but for much of a long career — he was actively publishing, in one way or another, from the First World War till the Eighties — he liked to give the impression of being more comfortable tending his garden in Sherman, Connecticut, than in the company of big-city intellectuals. On top of helping shape the story of the interwar avant-garde with his memoirs, starting with Exile’s Return (1934), he functioned as a critic, editor, teacher, minor poet, committee chair, and all-around literary middleman without ceasing to speak of himself as an interloper in “academic or bow-tie” settings. He’s remembered mostly as a rescuer of sinking reputations — his Portable Faulkner (1946) still gets credited with turning the novelist’s fortunes around — and in the postwar years he was inclined to leave the hurtful side of reviewing to younger practitioners. Slow of speech, hard of hearing, and — it was said — given to turning off his hearing aid at the first sign of unpleasantness, he had little trouble projecting an air of being above the fray.

Cowley’s father and grandfather were homeopathic physicians, and to his detractors, of whom there were quite a few, his literary dealings were similarly colored by well-meaning fraudulence, or worse. There were routine swipes from some of the people he wrote about: Ernest Hemingway, the beneficiary, in 1944, of his own Cowley portable, later observed in a letter to the young critic Charles Fenton that its editor knew “practically fuck-all” about his life. (Cowley, in turn, was fond of saying that Hemingway, though a fine writer, “could be mean as cat piss.”) Worse, younger critics had a way of implying that, far from being a high-minded old coot, Cowley was — and always had been — a slyly dedicated follower of literary fashion. Dwight Macdonald poked fun at the equivocations Cowley threw out when “confronted with a conflict between his taste and his sense of the Zeitgeist,” and Alfred Kazin, in Starting Out in the Thirties (1965), offered an acidulous portrait of Cowley in his pomp as literary editor of The New Republic during the Great Depression:

He was unable to lift his pipe to his mouth, or to make a crack, without making one feel that he recognised the literary situation involved. . . . I had an image of Malcolm Cowley as a passenger in the great polished coach that was forever taking young Harvard poets to war, to the Left Bank, to the Village, to Connecticut. Wherever Cowley moved or ate, wherever he lived, he heard the bell of literary history sounding the moment and his own voice calling possibly another change in the literary weather.

Kazin, a product of Brownsville, Brooklyn, and the City College of New York, made no secret of being rubbed the wrong way by Cowley’s Harvard-trained “ease and sophistication.” (In 1997, he wrote angrily of the peremptory manner with which Cowley had once addressed Bernard Malamud as “Bernie,” thereby making Malamud feel treated “as just another commonplace Jew.”) He also had a more directly political quarrel. Like Macdonald, Kazin had been affiliated with the anti-Stalinist left in the later Thirties. Cowley, by contrast, had let his Popular Front enthusiasms bounce him into the fellow-traveling camp, where he’d stayed put while much of the New York intelligentsia was heading noisily for the exit. This had made him, in Kazin’s summary, push The New Republic’s back half “in the direction of a sophisticated literary Stalinism,” with a widely noted editorial coolness toward Trotskyists, social democrats, and other alleged friends of fascism. During the Moscow show trials, Kazin recalled,

when his lead review of the official testimony condemned the helpless defendants accused of collaboration with Hitler and sabotage against the Soviet state, I felt that Cowley had made up his mind to attack these now helpless figures from the Soviet past, had suppressed his natural doubts, because he could not separate himself from the Stalinists with whom he identified the future. To Cowley everything came down to the trend, to the forces that seemed to be in the know and in control of the time-spirit.

According to this reading, the length of Cowley’s Stalinist period was a rare failure of his opportunist instinct. Though the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 made nonsense of his doctrine of antifascist solidarity, he didn’t publicize his doubts until the following summer, after Hitler had taken Paris. His change of heart came too late for The New Republic’s British owners, who relieved him of his position in 1940.

Still, just as he’d added some proletarian grit to his rather dandyish persona in the early Thirties, so in the early Forties he swapped Marx and cocktail parties for Emerson and trout fishing. Many matters had stronger claims on the world’s attention than did the shifting state of Cowley’s political consciousness, and his literary colleagues were, by and large, unfazed. Yet his activities in the Thirties proved to be a black mark against him in Washington, where in 1942 he was hounded out of a job at Roosevelt’s Office of Facts and Figures by the red-baiting congressman Martin Dies. (An article in Time portrayed a dutifully Audenesque poem he’d written about the Spanish Civil War as evidence of traitorous intent.) Cowley’s appointment to a temporary lectureship in Seattle attracted right-wing protests in 1949, and a similar campaign prevented him from teaching at the University of Minnesota two years later. On occasion, he was reduced to declaring himself “an old-fashioned Unpolitical Man” who believed “that Christ’s teachings are more profound than Lenin’s.”

By the time of the Minnesota episode, however, his rehabilitation was well under way. Cushioned by a grant from the Mellon Foundation, he’d reinvented himself as an Americanist with interventions in the cases of Nathaniel Hawthorne and F. Scott Fitzgerald as well as Hemingway and Faulkner. A revised edition of Exile’s Return, stripped of starry-eyed Marxist rhetoric, reasserted his credentials as a veteran of the now much-mythologized Twenties. By the end of the Sixties he more or less embodied the East Coast literary establishment — on the board of Yaddo, an editorial scout for Viking Press, a two-time president of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and so on — and in old age he piled up a sizable corpus of essays and reminiscences. All the same, there were jeers from aging Partisan Reviewers and, in the Eighties, neoconservatives. Myth-busting scholars also began to speak of his “incurably superficial” presentation of Faulkner and “amazing credulousness” toward Hemingway. After his death, in 1989, it was clear that the niche reserved in American memory for freelance men of letters of his vintage had been pretty much filled by his elder contemporary Edmund Wilson.

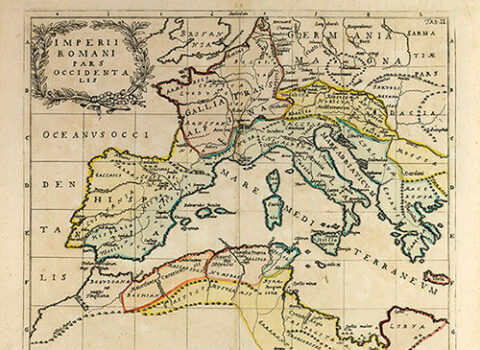

The Long Voyage, a selection of Cowley’s letters put together by Hans Bak, a professor at Radboud University in the Netherlands, aims to bring about a sympathetic reappraisal. Bak became friendly with his subject as a young researcher after contacting him in the Seventies: Cowley — unlike Wilson, “who gruffly declined such requests,” Bak writes — generally made himself available to fledgling literary historians. The resulting thesis, published in 1993 as Malcolm Cowley: The Formative Years, is an imposingly detailed study of its hero’s life before 1930, and the new book’s linking commentary and notes do much of the work you’d expect of a full biography. Bak — who chose from “an estimated 25,000” letters at Chicago’s Newberry Library alone — might not fully have kept his sense of proportion when it comes to Cowley’s place in the wider scheme of things. (He quotes, without apparent irony, a passage likening the destruction of The New Republic’s correspondence files from the Thirties to “the burning of the great library at Alexandria.”) Yet he’s a fair-minded and microscopically well-informed guide to the material.

On the evidence Bak presents, Cowley was a bit of an operator — he couldn’t have had the career he did without a feel for literary politics — but wasn’t the calculating, weather-vane-like figure his enemies enjoyed mocking. As even they acknowledged, his aw-shucks style was in place long before there was an urgent need for him to burnish his Americanism, and he was a stubborn booster of old friends, such as Conrad Aiken, after they’d fallen hopelessly out of fashion. In his writerly role, though, he seems to have been a man — as the Canadian novelist Morley Callaghan said of Ford Madox Ford — “of many models.” Some critics illuminate, or animate, the works they deal with by bringing their own personalities and preoccupations to bear on them. With Cowley, you often get the impression that the process worked the other way around. Equipped with wonderful self-belief and, in his friend Allen Tate’s words, a mind that was “basically concrete and unspeculative,” he tended to absorb the impress of whatever his nose for talent brought him up against.

Born in 1898, he grew up in East Liberty, a well-to-do Pittsburgh neighborhood. In spite of a history of thrift and industriousness — a granduncle had been an early partner of Andrew Carnegie’s before dying of prison fever during the Civil War — Cowley’s family had only a tenuous hold on middle-class respectability: they were regarded, he later wrote, “as being quite strange, if harmless, and too poor to clothe themselves properly.” His father, William, had been brought up a follower both of Emanuel Swedenborg and of Samuel Hahnemann, the inventor of homeopathy, and Cowley’s childhood relationship with this “impractical, wholly loveable man” mostly took the form of listening to nightly readings from Swedenborgian texts. Cowley’s main avenues of escape were the family’s farm near Belsano, Pennsylvania, where he worked in the summer, acquiring an unfeigned love of Nick Adams–style pursuits, and the local Carnegie Library. He set his sights on becoming a writer while in high school, and a scholarship took him to Harvard in 1915.

The earliest letters in Bak’s selection show Cowley soaking up the attitudes and mannerisms of the young bluebloods he encountered there. “I am a snob — hurrah, a true snob,” he wrote in 1916 to his hometown friend Kenneth Burke, himself a burgeoning, more abstract-minded critic. “Could anything be farther from the boy who used to associate with the social outcasts of a socially outcast highschool?” Along with teasing of this sort came a fair bit of boasting about Boston’s “disgustingly sensual night life.” He also learned, less endearingly, to sneer at “damned Jews,” and for several years his missives occasionally carried lines that Kazin would have viewed as confirmation of his darkest suspicions. They seem willed and pseudo-worldly rather than passionately hostile — a letter of 1922, for instance, makes fun of Harold Loeb, former “captain of the Princeton wrestling team,” in tones milder than those Hemingway would use of Robert Cohn, a stand-in for Loeb, in The Sun Also Rises (1926) — and in the course of the Twenties such passages stopped appearing. Cowley was ashamed of them later, monitoring himself for “latent anti-semitism” and writing his youthful nonlatency off as “the worst part of Harvard snobbery.”

As an undergraduate, he made contact with Aiken and the poet Amy Lowell, who advised him to smoke Dunhill pipes. (“She had found, she said, that the vulcanized bits didn’t bite through.”) He was conscious of a need to develop a “modern” sensibility but wasn’t initially sure how. The First World War — in which he served as a truck driver in northern France for six months in 1917 — showed him the way, partly by removing him from Harvard’s affectedly 1890s-ish literary scene, partly by providing a durable generational identity. In contrast to the conflict’s French, British, and German participants, young Americans serving overseas had had, he argued, a “spectatorial attitude,” a “monumental indifference” to the war’s official aims. Immunized against public cant, and given a taste of French culture (plus a favorable exchange rate), they returned to a United States that, thanks to Prohibition, was doubly unrecognizable. One couldn’t go home again, Cowley explained in Exile’s Return, so one washed up in New York, where no one seemed to have a future “beyond the swell party this evening and the disillusioned book he would write tomorrow.”

Being disillusioned about disillusionment turned out to be a useful stance for a young writer on the make. It helped, too, that Cowley knew how to hit a deadline. And he learned fast. “I have turned vers librist,” he announced to Burke in 1917, “just to show that I can write the nasty stuff.” By 1920, he was able to write knowingly about the life of an abstract painter — “you make queer marks on canvas that don’t represent anything except an emotion, and live on an allowance from your wife, who is in Paris” — and knew whom to call on to back up his musings about the “Youngest Generation.” Moving between the United States and France, where he spent two years on an American Field Service fellowship, Cowley got his name into many little magazines — The Dial, Broom, Secession — and had the requisite encounters with Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford, and James Joyce. He also apprenticed himself to Louis Aragon and Tristan Tzara, in whose company, in 1923, he punched the proprietor of a famous Left Bank café — a Dadaist gesture that only added to his mystique back home.

For much of the Twenties, Cowley had creative ambitions. Essays, though they paid the bills, didn’t count: only poems, novels, or plays were “to be considered as final ends.” “Lack of talent isn’t one of our chief problems,” he wrote to Tate in 1926. “Almost any of our friends has as much talent as Andre Gidé [sic] or Joseph Conrad.” Hart Crane was enthusiastic about Blue Juniata (1929), Cowley’s first book of poetry. But it was obvious to everyone, the author included, that Cowley did the modern movement more favors as a chronicler than he did when trying to embody it on the page. As with the early Pound — whose influence seeped into Cowley’s letters in the form of “fonetty kinglish” on “Amurricn” themes — his poems often look surprisingly hokey next to the work he championed in his prose.

Cowley was shrewd about his own shortcomings, though his mentions of them tend to bring in names commensurate with a more exalted sense of himself. “My mind is ordered, exact, and limited,” he wrote in 1922. He had, he felt, “the brain of Boileau and Pope and Congreve.” Paul Valéry, some of whose essays he translated, was another exemplar of the “instrumental mind” — a mind that “rusts like an unused tool” without external objects to work on — that Cowley believed himself to possess. “I was accurate, but not profound,” he wrote in the Sixties, looking back on his earlier critical efforts, and from time to time he brooded on “the need for depth.” Suggestions that he was shallow, however, annoyed him. His style, he told an impertinent researcher, was aimed at “the audience that Diderot had in mind for the Encyclopédie.” Burke was cleverer, he conceded, but lacked Cowley’s “special talents” for “writing a sentence or constructing an essay or editing a manuscript or (as happened yesterday at Yaddo) chairing a difficult meeting.” In old age he took to reading Samuel Johnson, “on whom I now find that I modeled myself.”

The journalistic clarity he came to prize in the Twenties was one of the attractions of communism in the Thirties. “I’ve noticed that even unintelligent reviewers can write firm reviews, hard, organised, effective, reviews, if they have a Marxian slant,” he wrote in 1931. “There must be something to it, I conclude.” The suffering caused by the Depression, and shock at the violence directed toward organized labor at home and abroad, made him far from alone in deceiving himself about Stalin. Yet his letters from the time make dispiriting reading, thanks chiefly to the speed with which he mastered the dialectical debaters’ tricks of the Third International. By 1936, “the Trotskyites” were as much the enemy as William Randolph Hearst; they used the word “Stalinists,” he complained, “in the same fashion as Hitler uses the word ‘Jews.’ ” “I’d never sacrifice a literary admiration to a political opinion,” he said, but he was soon admiring things along party lines, then writing lengthy, sophistic defenses of himself in response to reproofs from Edmund Wilson and others.

The cause of bringing him to his senses wasn’t helped by the fact that quite a few former Stalinists — though not, as he maintained, all of them — really were signing up with the forces of reaction. It was one thing to be branded “the literary cop who patrols the New Republic beat for Stalin” in a Trotskyist journal, another to see the charge repeated and amplified by professional ex-communists in the right-wing press. Learning the difference was a bruising experience. As a result, from the Forties onward, Cowley cultivated a tepid liberalism in public while wringing his hands over HUAC-type phenomena in his letters and occasionally dusting off his Harvard snobbery to characterize McCarthyites as an Irish-Catholic mob. Quizzed on the matter of “engagement” in 1968, he replied: “Look for me in the garden.” Given the payback he’d suffered in the early Forties, when he found himself hunting squirrels to feed his family after losing his job in Washington, it’s hard, in the end, to blame him.

It’s also hard to close his story on a minatory note. Bumptious, insiderish, and absurd as he sometimes was, he became an effective behind-the-scenes string puller in the cause of indigent writers. Though the big projects he dreamed of — among them a short history of American literature — were endlessly deferred, he’d learned enough from Marxism to wage a useful campaign against the New Critics’ pedagogically convenient insistence on bracketing great books off from history. Always more likely to be lambasted in an amusing takedown of something he’d overpraised than to write such a piece himself, he worked hard to preserve the memory of Hart Crane — with whom his first wife, Peggy Baird, improbably shacked up — and helped John Cheever, Jack Kerouac, and Ken Kesey along the road to publication. It’s true that he took Hemingway’s big talk too seriously and underplayed the guilt-drenched aspects of Faulkner’s South. Yet his introduction to Hemingway is more subtle than hostile critics such as Kenneth S. Lynn have made out, and in Faulkner’s case it’s possible that few people would know enough about Yoknapatawpha County to care about its politics if Cowley hadn’t put it on the map at a decisive moment.

Cowley’s correspondence also makes it possible to get a sense of him as a fairly stylish performer in his day, a sense that’s harder to get from the stuff he wrote for publication. Kazin — admiringly for once — described his reviewing in the Thirties as “shrewd, positive, plain, in the Hemingway style of artful plainness that united simplicity of manner with a certain slyness.” Thanks to the informal tone of the letters, you can just about see what he meant. “If I were a lady poetess, I should know how to reward you concretely,” Cowley wrote in reply to a kind review from the famously pontifical — and just as famously horny — Allen Tate. There are plenty of off-the-cuff character sketches (Sartre is identified to Faulkner as “a little man with bad teeth, absolutely the best talker I ever met”), and there are neat, if studied, snapshots of Twenties New York. Now and then Cowley hits exactly the right balance between hard-boiled bluster and insight — in a letter to Fitzgerald, for instance, comparing This Side of Paradise (1920) with Not to Eat, Not for Love (1933), a now forgotten Harvard novel by George Weller:

Weller is immensely more slick and sophisticated than you were then. His book is more complex than yours was, and better, too. Except there is this remark to make: Weller had his literary models (Dos Passos and Thomas Wolfe); all he had to do was copy them, fill out the appropriate blank to Parnassus with which they furnished him. He filled it out damned well. You didn’t have a blank. You were trying to say something that hadn’t been said. Weller is good, but isn’t making history.

It takes one to know one, Weller’s ghost might reply, adding that it’s Edmund Wilson, not Cowley, who’s remembered as the savior of Fitzgerald’s reputation. Even so, Hans Bak’s efforts have breathed a bit of life into — without making completely persuasive — Cowley’s late-life claim: “Look, I’m not a diplomat or ambassador of letters and bringing together the divergent interests of the literary community isn’t my ‘chief virtue.’ My chief virtue is to have written well.”