Most nights during the early summer of 2011, Chukwuemeka Ene would slip out the back door of a bungalow in Jackson, Mississippi, and make his way to a nearby convenience store. He didn’t mind the Deep South’s steamy heat; it reminded him of the climate in his hometown of Enugu, Nigeria. Ene was seventeen years old, but at six feet three inches tall, he might easily have been mistaken for a man in his twenties. This was particularly true when his broad features took on a brooding expression — and in Jackson, he wasn’t smiling much. Back at the house, two younger Nigerian boys were waiting for him to return with the three loaves of white bread he ritually procured during these expeditions. The boys slept together on the floor of the living room, with one pillow shared among them. Formal meals were limited mostly to sporadic drive-throughs at fast-food restaurants.

That left Ene and his companions — lanky teenagers whom I’ll refer to by their nicknames, Ben and Dixon — perpetually hungry. They had arrived in the United States just a few weeks earlier, hoping to be groomed for college athletic scholarships, and their days were spent on intensive basketball drills and pickup games at the Jackson YMCA.

Ene had discovered the sport at the age of fifteen, when he stumbled across a game in a local park on his way to visit a cousin. He was mesmerized by the boys hustling back and forth, yelling for the ball. After the game wound down, he took a few tentative shots of his own — and the next day, he returned and joined in the play, shredding a pair of flip-flops in the process. Basketball quickly became an obsession. When Ene wasn’t in class, he was playing with a local high school team or at the park. Sometimes he even slept there, near the court. Passions ran high: once, after an argument over a call, an opponent jumped Ene on his walk home and stabbed him in the hand, just below his thumb. After a trip to the hospital for stitches, Ene returned the following day and worked on dribbling with his nondominant hand.

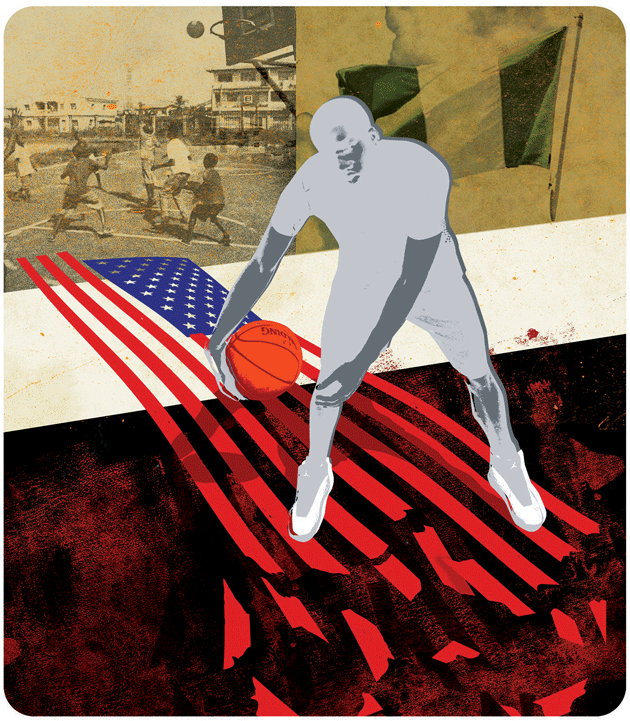

His prowess at alley-oop passes soon earned him a nickname: Alley. He also won a spot in Nigeria’s national basketball program, beginning with its under-sixteen team. According to Ene, his slavish devotion to the sport infuriated his father, particularly when the tournament schedule required him to miss school. The more Ene learned about the economics of the sport, however, the more convinced he became that it could serve as a social conveyor belt. His family wasn’t well off; they lived in a village on the outskirts of Enugu and operated a poultry farm. But a satellite dish beamed ESPN into their living room, and during marathon viewing sessions Ene learned how transformative basketball had been for a figure like Michael Jordan, catapulting a kid from small-town North Carolina to global stardom.

Ene’s dreams of life in the United States were further burnished by the ongoing migration of his teammates. In one season alone, half a dozen boys on the roster left for the United States, scooped up by scouts and coaches on the hunt for tall, talented players. Ene’s former teammates posted photographs of themselves on Facebook, decked out in Nike high-tops and jerseys, dunking with one hand. Their departures and glamorous reappearances on the Web nagged at him. So when a teammate told Ene about Sam Greer, a man who reportedly brought Africans to the United States to play high school and college basketball, Ene sent an email. He received a terse reply: “Send me a clip so I can see if you can play.”

Greer must have liked the video Ene passed along, because he told the teenager he would take him on. He also asked him to identify other, taller, younger kids who were good players. Ene sent clips of Ben (six feet eight inches) and Dixon (six feet nine inches), both of whom he had met at the park. Greer scooped them up as well. He sent all three boys the paperwork they would need for their visas, and coached them in advance of their consular interviews. “By GODS grace,” Ene wrote Greer, “everything will go well.”

It didn’t. Instead, Ene was to learn that in the unsparing economy of youth basketball, he was little more than a commodity. Players destined for a professional career, or even a spot on a powerhouse college team, are lavished with attention and often slipped cash and gifts. The others are generally cast aside. This rejection would be devastating for any young person — but when foreign players are deemed poor bets, as Ene ultimately was, they’re often left to fend for themselves, halfway across the world from their families, in a country with no formal safety net for undocumented foreigners.

It was in the 1980s, with the rise of the seven-foot Nigerian center Hakeem Olajuwon, that U.S. basketball mandarins began looking to Africa for talent. Olajuwon starred at the University of Houston before going on to a Hall of Fame career with the Houston Rockets and the Toronto Raptors. Like many Africans, Olajuwon was originally a soccer aficionado; he didn’t convert to basketball until his teens, when a fellow student pressed him to play for the school’s team. His ball-handling skills eventually brought him renown, and Guy Lewis, then the coach at the University of Houston, offered Olajuwon a scholarship. Yet the Nigerian center wasn’t initially treated as a prized recruit: when he first landed in Houston, in 1980, no one even bothered to pick him up at the airport.

The other African star of the era was Dikembe Mutombo, who was born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, starred at Georgetown during the 1980s, and went on to play for several NBA teams, becoming one of the best defenders in the history of the league.

The second wave of players from the continent didn’t replicate these successes. In fact, Africans accounted for two of the most notorious draft busts in recent NBA history: Michael Olowokandi, from Nigeria, and Hasheem Thabeet, from Tanzania, both of whom went on to disappointing (and, in Olowokandi’s case, prematurely truncated) careers.

One reason Africans haven’t made a bigger mark on U.S. basketball is that soccer is still the dominant sport on the continent. Africans tend to take up hoops as teenagers, by which time their elite American counterparts will have dedicated hundreds or even thousands of hours to the sport. An infinitesimal number of people have the innate gifts, as Olajuwon did, to compensate for a late start. The NBA has attempted to raise the sport’s visibility in Africa through its Basketball Without Borders camps, which have been held for the past dozen years in Johannesburg, and more recently in Dakar. A handful of NBA players and scouts also sponsor their own camps. For example, Luc Mbah a Moute, a forward for the Philadelphia 76ers, holds an annual showcase in Cameroon, his home country, where he spotted the latest star African import, a seven-foot center named Joel Embiid, who now plays for the same team.

Still, despite these institutionalized paths to the United States, most Africans are recruited through informal channels. Teenagers do a lot of importuning: American coaches often find their email inboxes clogged with missives from African players seeking opportunities abroad. But enterprising coaches have also developed their own recruiting networks. Eric Jaklitsch, for instance, is an assistant coach at Our Savior New American, a private Lutheran school in Centereach, Long Island. He has assembled one of the country’s finest high school basketball teams in part by plucking players from Africa — where he has yet to set foot. Instead, he relies on scouts like Tidiane Dramé, the self-anointed “King of Mali,” who helped to identify Cheick Diallo, a towering Malian power forward. Diallo was one of six African players on the school’s 2014–15 roster — a number that has prodded some observers to dub the team “Our Savior Few Americans.”

Sam Greer appears to have assembled his own web of contacts in Africa. In a phone conversation, he told me that he first visited the continent decades ago, as part of a Christian ministry raising awareness about AIDS. According to a longtime coach in Memphis, Greer was then a local “runner” — a street scout who identified players in and around the city. It seems that Greer upgraded from regional scouting to international recruitment by amassing an insider’s knowledge of African basketball. Indeed, Ene had marveled that the American recruiter was as conversant as any local fan with the Nigerian team’s junior roster.

Greer says that he has brought approximately 250 foreign players to the United States. He also claims that recruiting isn’t his day job: he told me that he works for the federal government, though he gave no indication of his duties or whether they had helped him to target African players. (Officials at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and the Department of Homeland Security say he isn’t on their payrolls.)

In any case, Greer’s emails to Ene convey an insider’s savvy about both the technical process of obtaining a visa and the image the boys would need to project to U.S. Embassy staff. He explained to Ene that the key bit of documentation the boys would need for their applications was a letter from a school superintendent in Corinth, Mississippi, confirming that they would be attending high school and would stay with a host family who was covering their fees. These letters arrived in Nigeria in March 2011. They made the boys eligible for I-20s: certificates they could use to apply in turn for F-1 visas, which would allow them to live and study in the United States until they graduated from high school.

There are no official records of how many Africans come to the United States to play sports, since recruits aren’t required to identify themselves as such. (Greer instructed his charges not to breathe a word about basketball when they visited the U.S. Embassy in Abuja.) But athletes are much more likely to apply for the F-1 than for the J-1, a cultural-exchange visa with stricter requirements. In 2013, 4,132 F-1 visas were granted to Nigerians, compared with 640 J-1s.

Ene was elated when he received word that his F-1 application had been successful. “Life is going to start,” he remembers thinking. “I’m going to be good.” Ene’s father, however, was appalled by his son’s plan to leave Nigeria, especially because it was facilitated by a sport he reviled. When it became clear that Ene was leaving, his father renounced his parental rights and refused to pay a penny for the airline ticket, forcing his son to solicit donations from friends and relatives.

Despite this showdown, Ene didn’t dwell on the fact that his sole contact in the United States was a complete stranger. “It was America,” he later recalled. “What could go wrong?” He might have seen warning signals in Greer’s emails, which were laced with admonishments that can be read either as concern for the boys’ safety or as preemptive assertions of control. “Remember I will be the person to handle everything for you, and no one will control you I promise that,” he wrote in one email, “so when in America you must tell me everything that goes [on].”

Greer’s insistence on being the boys’ primary custodian, even as he was sending them to live and train with other people, spoke to his knowledge of elite youth basketball. The payoff for identifying talent and securing a young player’s loyalty can be enormous, especially if that player blossoms into an NBA star. Sometimes the payoff is direct: successful pros may share part of their windfall with the people who guided them. Other times it is indirect, but no less lucrative: coaches and agents have been known to provide gifts, cash, and jobs to recruiters who deliver top players to their rosters or client lists.

Reaping such rewards, however, depends on a tight personal connection with the player. Serving as a father figure, or even just a buddy with a bulging wallet, may be enough. But with foreign players, marooned in a strange land with little in the way of cash or connections, this sense of indebtedness can be established in more formal ways. Which may be why Greer wrote Ene before he arrived: “I want to make sure for no reason any one get guardianship but me because I really don’t trust to [sic] many people in America.” Ene, too, would soon come to share that sense of wariness about other people’s motives.

The YMCA in Jackson has a spartan quality. The windows don’t admit much light, and the floor could use a coat of polish. What impressed me, during my visit one April afternoon, was the players. For a quarter of an hour, I watched members of Omhar Carter’s MBA Hoops team run a layup drill, and no one missed a single basket. The standout was a fifth grader named Mason Manning, whose hands moved so swiftly they resembled a blur of butterfly wings. (I later found a YouTube clip in which he calmly dribbles two balls between his legs; it had more than 40,000 views.)

MBA Hoops is considered by many the best Amateur Athletic Union team in Mississippi. The AAU, founded in 1888, is nonprofit, mostly volunteer, and — well, amateur. Yet the word is something of a misnomer, because the organization has a noticeable patina of professionalism. Teams operate year-round, flying across the country to play in tournaments and showcasing children as young as six. The exposure the AAU circuit provides makes participation de rigueur for any player with hopes of landing a college scholarship or embarking on a professional career. Virtually every U.S.-born NBA star — including the past two M.V.P.’s, Kevin Durant and LeBron James — played for AAU teams. And companies like Adidas, Nike, and Under Armour are eager to donate shoes, uniforms, tournament entry fees, and cash for expenses.

This puts extra pressure on AAU coaches to constantly enlist new talent. And that pressure helps explain why Omhar Carter was receptive to a pitch he received in early 2011 from Greer, whom he hadn’t previously encountered, to house and coach three Nigerian players, two of whom were over six and a half feet tall. According to Carter, Greer described himself as the middleman for any African player coming to the Deep South. “Now that I look back on it,” Carter told me, “with him being in Memphis, I should’ve looked into it a bit more.”

That June, Carter and Greer picked up the boys when they arrived at Memphis International Airport. Carter drove the boys directly to Mississippi and left them at a female friend’s house in Jackson. Once they had dropped their bags, their host said that they would be sleeping on the floor of the living room. Ben and Dixon asked Ene in their native Ibo whether they should protest, but Ene shook his head. Carter, he figured, must still be setting up a separate bedroom in his own home. Give it time, he counseled.

The next morning, according to Ene, Carter picked up the boys and drove them to the gym without providing breakfast. Apparently there had been some confusion about who would feed them. Over the next few days, Carter treated the boys to an occasional fast-food meal, but not surprisingly, given their long hours at the gym, they were always hungry. And so Ene began his nocturnal shopping expeditions, buying bread and occasionally cookies and Gatorade with funds left over from the collection he’d taken up to pay for his plane ticket. While this was going on, the boys were settling into a routine of high-tempo drills in the morning and games against college athletes at night. They practiced for other coaches too, in sessions that felt like unacknowledged tryouts.

To Ene, the situation began to resemble a form of servitude. It wasn’t just the dearth of food or proper beds, but the lack of autonomy. The boys had no access to a computer, so they couldn’t communicate with their parents or with Greer. And Ene was increasingly desperate to make contact, because Carter had taken possession of their passports. (Carter told me that he held the documents to keep them from being stolen, but his charges saw it as a way of exerting control.)

When Carter brushed away Ene’s complaints about the passports, Ene bought a SIM card for his Nigerian phone at the convenience store. He called Sam Greer. “Get us out,” he said, “or I’ll go to the police.” The scout counseled against involving outside authorities and said that he would settle things with Carter. Soon enough, Carter returned the passports and drove the boys to Corinth High School — which they were supposed to be attending in the first place. There they toured the facilities and played for the coach but were never formally enrolled.

Before the summer was over, Greer said he would remove the boys from Carter’s care. Chris Threatt, the varsity head coach at McClellan Magnet High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, would host them instead. Greer bought the boys train tickets from Jackson to Memphis. When they arrived, he treated them to burgers and apologized for what he later described to me as “the buzz saw” they had encountered in Mississippi.

While his team finished practicing, Omhar Carter and I sat down at a wooden table in the lobby of the Jackson Y. Grunts emanated from the weight room nearby. Although Carter looked like he, too, had put in his time there, he didn’t come across as intimidating. Rather, he was gracious and good-humored. During drills with the team, he had mixed flashes of toughness with playfulness, teasing one of his players when the boy took off his shirt. “Really, Marie?” he asked. “Is that necessary?” Marie, it turned out, was from Nigeria, as was another player, whom Carter identified as Emmanuel. The two boys had been easy to spot during practice; they towered over the others.

Emmanuel and Marie were the first African players Carter had taken on since Ene, Ben, and Dixon had left. He had sworn off coaching foreign players for a while after the mess with Greer’s recruits, and signed up Emmanuel and Marie only after meeting them through an African student at a local college. The two were still enrolled at a high school in Florida but were in Jackson to train during spring break.

Carter disputed Ene’s claim that the three boys weren’t cared for during their time in Mississippi. He said that he had provided breakfasts for his players in hotel-buffet quantities, with pancakes, bacon, and sausage, and that the boys had stayed in his house for a time, where they had their own room and their own beds. In his account, the homestay at his friend’s house was comfortable, too: Carter described a living space with a “huge bed, a big, huge couch,” bookshelves, and a television.

He attributed Ene’s disgruntlement to the role the boy had been forced to assume. It was Greer, Carter told me, who had presented Ene as a kind of uncle — the caretaker of the two younger, taller, more desirable recruits. “No one wanted him,” Carter said. “It was a package deal.” He also felt that the boys had made little effort to integrate themselves into his team. “They would always go off into a circle and they would talk in their language,” he recalled. Their insular behavior frustrated him, since he was providing them with clothing, coaching, housing, food, and transportation. But their ultimate allegiance seemed to be to Greer. “At the end of the day,” he told me, “whatever Sam said, went.”

Carter and Greer haven’t spoken since. After one of Carter’s current Nigerian players distinguished himself at a local tournament, however, Greer apparently contacted the boy’s father. Carter pulled out his cell phone and read me some of Greer’s messages, which had been forwarded to him by the family: “I got a call about the two boys who were in Florida. But they are hiding out in Mississippi. Those boys can go to jail if they get caught.” Greer meaningfully noted that he had a friend who worked at the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System, the government program that supervises I-20s. “It’s no problem with me,” he continued. “But there seems to be some funny business.” The players had been freaked out by the implication. “If you are from Africa and you hear that Homeland Security is going to pick you up,” said Carter, “that’s scary.”

Greer’s veiled warning to the Nigerian boy’s father was likely an effort to poach the players. According to Carter, Greer recoups the money he spends bringing kids over to the United States by sending them to college teams that pay him a fee. “It’s like an auction,” Carter told me. “Each kid is an item to sell.”

Such poaching isn’t unusual, especially at the AAU level, because landing a superstar player can be extraordinarily lucrative. (After recruiting and grooming the future NBA star Tyson Chandler, an AAU coach named Pat Barrett was rewarded with a reported $200,000 when his protégé signed with the Chicago Bulls.) Nor is it uncommon for a player to compensate members of the network that embraced him as a teenager. In 1997, as an eighteen-year-old rookie with the Toronto Raptors, Tracy McGrady signed a $12 million endorsement deal with Adidas — which stipulated payments of $900,000 apiece to his high school coach and the scout who had discovered him.

Generally, however, the payoff for AAU coaches comes from agents, colleges, or pro scouts seeking to curry favor with a recruit. Sometimes these bribes are cash transactions; other times, they take the form of career advancement. Though the NCAA made efforts to curb the practice in 2010, colleges have long recognized that they can reel in top freshman prospects by hiring their AAU coaches. In 2006, for example, Kansas State lured a coach named Dalonte Hill away from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, in what appeared to be a blatant attempt to land Michael Beasley, whom Hill had coached during his AAU days. The strategy worked. Beasley ditched an offer from U.N.C. Charlotte and signed with Kansas State. By 2008, the university was paying Hill a reported $420,000 per year.

“America is not the place I thought it was.”

Three years after receiving that text message from Ene, Chris Threatt still remembered it word for word. Greer had put Ene in touch with the McClellan High coach, presumably to bolster the case for taking in the three Nigerians. Threatt had two teenage daughters and years of experience at McClellan, whose varsity team won the Arkansas state championship in 2010. “I get satisfaction from helping,” Threatt told me. If the Nigerian teenagers were in distress — and showed the promise Greer had touted — taking them in seemed like the natural thing to do.

For two months, the three boys lived with Threatt in Little Rock. According to Ene, it was a decided upgrade from Mississippi. They were fed, had their own beds, and attended church with the coach’s family on Sundays. A collection taken up from the congregation paid for clothes and school supplies.

The boys were soon joined by a fourth Nigerian player and Greer recruit, whom I’ll call Kelvin. To relieve the crowding, they were divided among three households: Kelvin was placed in the home of an acquaintance of Threatt’s, while Ene was sent to live with one of Threatt’s assistant basketball coaches. Kelvin, Ben, and Dixon landed spots on Team Penny, one of the best AAU programs in the South. Threatt took an assistant-coaching position with the team and began driving the boys to and from Memphis on weekends for practice and tournaments.

Soon, though, the boys received stunning news: because they had neither been registered at Corinth High School nor had their I-20 forms transferred to their new school, they were in the United States illegally. The three host families proposed to set things right by adopting their guests. Threatt told me the offer sprang principally from altruism, and noted that adoption would have shielded the boys from deportation and allowed them to receive health insurance. This was particularly important for the three Team Penny players, who would be at greater risk of injury.

There were, however, legal barriers to the adoptions. And for Ene in particular, returning to Nigeria was no longer a possibility, given the fallout with his father. He hoped to attend college, and had maintained a 3.86 G.P.A. at McClellan, but as a foreign student, he found it difficult to apply for financial aid. His visa status barred him from playing on the high school basketball team, which meant that he had no way to attract attention from college coaches. Greer arranged a tryout for Ene, at LeMoyne-Owen College, in Memphis, but nothing came of it. Ene remembers the days after graduation as agonizing. “I was just sitting around, doing nothing,” he said. When an aunt offered to let him live with her in New York City, he quickly boarded a Greyhound bus from Little Rock to Queens.

Back in Arkansas, the other boys’ relationships with their host families deteriorated, then became openly hostile. An anonymous tip to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center led agents from the Department of Homeland Security to visit the home where Kelvin was staying, on January 1, 2013. The agents determined that he had not in fact been trafficked, but they confirmed that he wanted to leave. The following day, they interviewed Ben and Dixon, who also said they wanted out. All three were transported to a juvenile-immigration shelter in Chicago, and are now in foster care in Michigan.*

Threatt was shaken by this denouement. “The police came to my house,” he said. He added that one of the younger boys had consistently defied his host parents’ rules. Notes made by the DHS agents buttress his argument, describing the coach and another host parent as disciplinarians but finding no evidence of abuse.

At least one DHS agent speculated that the homestays blew up because the players weren’t racking up impressive stats on the court. It’s not an easy proposition to land a spot on Team Penny’s roster, but the boys were regarded as aspirational prospects at best, unlikely to attract attention from major college programs, let alone the NBA. “They weren’t getting the result they wanted,” Ene said. “Maybe that’s why things changed a little at the end.”

People who bring athletes over from Africa tend to cast themselves as Father Flanagans. Greer, for example, told me he’s in it “to help kids.” But given the rewards of landing a tall, talented player, there is obviously potential for exploitation. George Dohrmann, the author of Play Their Hearts Out (2010), argues that the NBA should acknowledge that the AAU is a cesspool and impose more rigorous supervision. European soccer, in which professional teams run their own academies to identify and train the rising generation of talent, could serve as a model. If this system were transferred to the United States, a young star in New York would play for the Knicks’ academy team, under the oversight of high school athletics regulations, and be given the chance to work his way up to the team’s roster. If he turned out not to be NBA caliber, he could still pursue college or play abroad.

Ohio has taken the step of barring foreign students on F-1 visas from playing high school sports. “We believe the F-1 is ripe for abuse,” Deborah Moore, an associate commissioner for eligibility at the Ohio High School Athletic Association, told me. The prohibition followed in part from a 2001 incident in which a scout from the Central African Republic recruited at least nine athletes to play soccer and basketball for Dayton Christian High School, in Miamisburg, then filled out the prospective students’ F-1 visa applications with the names and addresses of host families who were unaware that they were being listed. Foreign students who move to Ohio without their parents and want to play sports must now have a J-1 visa unless they’ve been adopted by an American citizen.

Nevertheless, Moore said, people keep trying to skirt the regulation. In fall 2013, the athletic director at Talawanda High School, in Oxford, Ohio, received a visit from a towering Nigerian student and his purported guardian, who wanted to enroll the teenager and have him play basketball there. When the guardian was informed that the boy was ineligible, he soon found a willing school in a different state.

Farther south, Sam Greer’s African scouting has continued unabated, and he reportedly landed a big score from Ene’s hometown of Enugu: Moses Kingsley, a six-foot-ten-inch forward who entered the University of Arkansas in 2013 as a top-fifty recruit. Kingsley had the smooth ride of a truly elite player. He attended Huntington Prep, a basketball powerhouse in West Virginia, and apparently forged a close relationship with his host family in Proctorville, Ohio. “Miss my Host Family!” he tweeted in July 2013. “Miss the good laughs.”

Things got even worse for Ene a few months later, when his aunt’s landlord pointed out that the young man wasn’t listed on the lease, and he was forced to move out. Now he had nowhere to go. Through a search on the Web, he found a Harlem nonprofit called African Services Committee (ASC) and showed up there hauling two bags. “It was like he was going to board a flight,” said Jessica Greenberg, an attorney with the organization, who immediately suspected that Ene was homeless. She phoned around but was unable to find him a bed — the nineteen-year-old would have to spend the night at a men’s shelter.

He returned to the ASC office the next morning with a shell-shocked look on his face. The staff had warned Ene to keep his belongings close at hand, so he had clung to his baggage all night long. Another attorney, Kate Webster, called Covenant House, a center for homeless youth, and insisted that they provide a bed for him. “We are talking about a trafficking victim,” she said.

Meanwhile, Ben and Dixon were being assisted by the Polaris Project, an antitrafficking nonprofit. Ene called the organization so frequently to check up on his former companions that the receptionist came to recognize the sound of his voice. He displayed similar initiative in fixing his visa status. After one of his initial consultations at ASC, Webster left him at a computer while she went to make some photocopies. “I figured he would download a video game,” she said. Instead, when she returned a few minutes later, she found him researching the U visa, which is reserved for immigrants who have been the victims of a crime. “Maybe,” he asked her, “I would be eligible for this?”

In the end, Webster counseled Ene to put in a petition for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. Originally created in 1990 for undocumented children in foster care, it was later expanded to include kids who could prove they had been the victims of abuse, abandonment, or neglect at the hand of a parent or guardian. In 2013, one of the most traumatic experiences of Ene’s life — his father’s official renunciation of his parental rights — resulted in his receiving a green card.

The moment you see Ene’s wingspan, it becomes clear why Sam Greer wanted to bring him to the United States. Its breadth was on ample display one afternoon in late March of last year, when he was asked to keep early arrivals out of the main foyer of Covenant House, where recruiters like Modell’s Sporting Goods and the U.S. Army had set up booths as part of a job fair. He executed the assignment zealously, arms wide. “It’s not time yet,” he told a group of teenagers jostling to get by. “Just trying to get hired, man,” a boy said. Ene was implacable: “That’s why we are all here.”

While Covenant House doesn’t generally hire interns for its Career Development department, an exception was made for Ene. He spent his mornings helping residents prepare résumés and conduct job searches, then went to work as a security guard at a Queens library in the evenings.

In June, he arranged for another Nigerian basketball player whom he knew from pickup games in Enugu to live at Covenant House. Through the boy’s Facebook posts, Ene learned that he had been brought over by a scout to compete in an AAU tournament in Georgia. On arrival, the player had discovered he would not be placed with a host family. Instead, he spent months sleeping in a poorly ventilated gym.

That yet another Nigerian had been coaxed to the United States with false assurances deeply riled Ene. “It’s like modern slavery,” he said. “It’s not slavery where they put a chain on your hand or your neck. But it’s people trying to use you.” He didn’t attribute this behavior to racism per se — after all, everyone who had been involved in his transplantation to the American South, including Greer, Carter, and Threatt, was black. Nor did he hold Greer or Threatt responsible for his ill treatment. “You can’t put them all in the same shoe,” he insisted, while rejecting the implicit argument that any experience in the United States was a step up from what awaited Nigerians back home. “What kind of good life are they giving us, telling us to sleep on the floor?” he asked me. “I didn’t take it like a good life.”

By late summer, Ene still hadn’t had the chance to talk at length with the new Nigerian at Covenant House. He was working twelve-hour days and saving money for college. He no longer harbored dreams of a basketball scholarship. “I still like the game,” he said. “But it’s a dirty business. I don’t want to get involved in it again.”