You never step in the same river twice, but a rival you step on constantly. “Everything flows” — including anger and resentment. According to Socrates, according to Plato, the original Greek of Heraclitus’ fragment was Panta rhei, the verb of which streamed into the Latin rivus, meaning “rivulet” or “brook.” A derived term (derivare: “to draw off water”) was rivalis, meaning “a person with whom you share a river.” And so we have “rival”: a person who fishes the same waters as you — a person who, if wishes were fishes, would drown.

Richard Bradford’s Literary Rivals: Feuds and Antagonisms in the World of Books (The Robson Press, $24.95) is the perfect volume to pack, if not for an embankment picnic, then for a visit to the water closet, sectioned as it is into discrete, short-sitting chapters, each concerning a pair of adversaries fighting over, and in, paper scraps. The backbiting and cant collected here tend toward the shallow, though deeper significance can be found in the fact that this annals of argument skips Greece (Epicureans vs. Stoics), Rome (the libelli vs. the Gospels), and most of continental Europe (poison-pen stabbings and pistols at dawn) in favor of the paltrier grudges of the Anglo-American novel — between Samuel Richardson (who was also a printer) and Henry Fielding (who was also a journalist), Dickens and Thackeray (both of whom were journalists), and Twain and Bret Harte (both of whom were both printers and journalists). Modern literary rivalry appears to be about who is, and is not, getting published, paid, and famous.

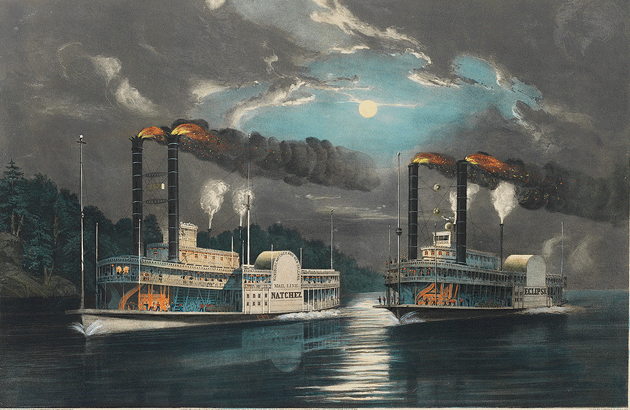

A Midnight Race on the Mississippi, based on a sketch by H. D. Manning © The Museum of the City of New York/ Art Resource, New York City.

The matter of Twain vs. Harte might seem trivial now, but in the 1860s it was a dispute over who held title to the Mississippi and all the territory to its west. California was full of gold, silver, and bullshit back then, and Twain and Harte both staked claims with mining tales — “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and “The Luck of Roaring Camp” — that brought them national attention. Once they’d established their reputations, Twain left to prospect Europe and Palestine for The Innocents Abroad, while Harte stayed home on the range and repeated himself into regionalism.

Still, no amount of Roughing It or Gilded Age success could erase Twain’s memory of the threat Harte had once posed. Nor could Twain forget their disastrous 1876 collaboration on a racist play, Ah Sin — not an exclamation of vice but the name of a Chinese railroad worker — for whose failure Harte sought damages. Broke, abandoned by publishers, and desperate to duplicate Twain’s achievement by escaping overseas, Harte applied for an ambassadorship to China, but Samuel Clemens showed no clemency, asking William Dean Howells to alert President Hayes: “Wherever [Harte] goes his wake is tumultuous with swindled grocers, and with defrauded innocents who have loaned him money. . . . He can lie faster than he can drivel pathos.” Harte was denied the post but appeased with a lesser ministerial position in Prussia, which Twain, writing to Howells again, also tried to undermine: “Tell me which German town he is to filthify with his presence; then I will write to the authorities there.”

Literary Rivals is its own sort of betrayal, in that it alerts readers to what writers have always feared: that their fiction might not be as entertaining as their fights. Edmund Wilson trashed Nabokov’s translation of Pushkin, publicly because of its prosody but privately because Nabokov had based Humbert Humbert on the protagonist of a Wilson story (whom Wilson had based on himself). Sinclair Lewis accused Theodore Dreiser of plagiarizing his wife; Dreiser responded that he’d done more than plagiarize her — though cuckolding Lewis was no compensation for missing out on the Nobel. The lesser chapters of Bradford’s book ask readers to choose between novelists who often did their best work, and made their worst decisions, as critics: Capote or Vidal? Vidal or Mailer? Mailer or Wolfe? Rushdie or Khomeini? Opposition may be true friendship, as Blake once proclaimed, but it’s a meaningless way of forming a canon. Canons form themselves, in an unconscious natural flux, like

a majestic river, the sound or sight of whose course you caught at intervals, which sometimes was concealed by forests, sometimes lost in sand, then came flashing out broad and distinct, then took a turn which your eye could not follow.

That’s how Wordsworth described a lecture by Coleridge. There was, he said, “always a connection between its parts and his own mind, though one not always perceptible to the minds of others.” He wasn’t being nice.

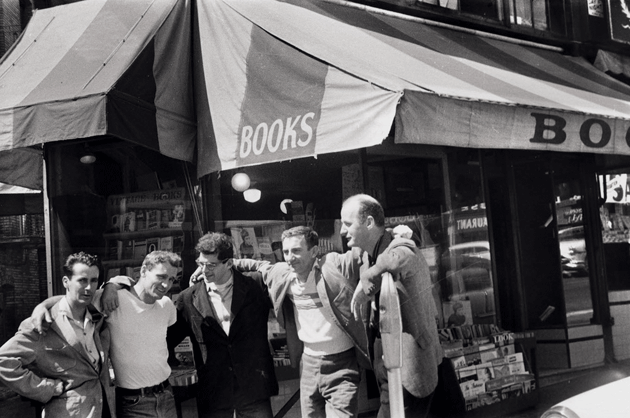

In 1855 Emerson read Leaves of Grass and wrote to Whitman: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.” A century later, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the poet-founder of City Lights Books, quoted that line in a telegram to Allen Ginsberg, appending a query: “WHEN DO I GET MANUSCRIPT OF ‘HOWL’?” Whitman blurbified Emerson’s line by slapping it on the spine of future editions, without Emerson’s consent; Ginsberg sent Ferlinghetti his poem, and City Lights published it, following it with dozens of titles by both correspondents and, now, with their four-decade correspondence itself.

I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career (City Lights, $26.95) collects the back and forth of a patient editor and his house’s bright star, who, when he wasn’t trying to be the next Whitman (the beard, the bulk, the breathless lists) or Coleridge (the metaphysics of debauchery), fancied himself a literary agent, P.R. rep, and distributor — a one-man Amazon.com, fueled by cigarettes, amphetamines, and ayahuasca. Ginsberg’s every missive was an emetic brew of the selfish and the selfless: pages of text ordering Ferlinghetti to contact the ACLU (and UPI, Time-Life, the Village Voice, the Library of Congress, and the UC Berkeley English department) to handle Howl’s obscenity trial, supplemented with postscripts advising him to acquire manuscripts by Philip Whalen and Gary Snyder, whose faux-Eastern poems “speak Jappy,” which Ginsberg meant as a compliment. Ginsberg’s own deal with City Lights was a handshake, with a middle finger raised to the three-martini-lunch crowd at Knopf. As Ferlinghetti put it in a 1957 dispatch to Tangiers, where Ginsberg was cavorting with Burroughs:

The hell with contracts — we will just tell [other publishers] that you have a standing agreement with me and you can give me anything you feel like giving me on reprints whenever you get back to the States and sit in Poetry Chairs in hinterland CCNYs and are rich and famous and fat and fucking your admirers.

The anxiety of influence soon gave way to the anxiety of affluence: Ginsberg wrote that “San Francisco stuff” was in wild demand in Paris, where he was holed up on the Rue Gît-Le-Coeur in a hovel later rechristened the Beat Hotel (now €280/night). From Amsterdam, he predicted that if Ferlinghetti published Kerouac and Gregory Corso, “we could all together crash over America in a great wave of beauty. And cash.”

Left to right: Bob Donlin, Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, Robert LaVigne, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1956 outside City Lights Bookstore, in San Francisco © Allen Ginsberg/CORBIS

Ferlinghetti, for his part, remained caustic, cautious, and discerning: he said yes to Kerouac and Corso, and no to Whalen, Snyder, and Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg’s lover: “You’re a movement in yerself,” he wrote, “but you carry this little band of cohorts around with you in portfolio like a prospectus for the Revolution . . . and I’m not out to run a press of Poets That Write Like Allen Ginsberg.” Instead, he was out to write, like and for himself (about Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind, Ginsberg confessed: “I hardly had [a] chance to glance at it”), producing a corpus of sturdy, politicized verse whose casual gruffness rhymed with the editorial guidance he had to offer:

Here [in Section II of Kaddish] I find still some repetition or what seems like repetition to the outside reader, tho not to you — to you, every detail counts whether repeated or not, etc. And I think you can improve the dramatic effect of the whole by some slight cutting . . . (I know there are dear phrases which are like pulling teeth to take out) but since this section has to sustain itself in the midst of other sections of pure poetry, if it were just a very little shorter, the effect of the whole would be more potent.

But if you want it just as-is: OK.

The Ferlinghetti–Ginsberg letters took weeks or, if accompanied by books, months to travel between San Francisco and whichever American Express branch or sublet was receiving Ginsberg’s mail. The Inklings, by contrast, delivered their criticisms in person. For more than two decades, this club of Oxford dons and the aspiringly donnish — including J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, and Charles Williams — met weekly to read their works in progress: Thursday evenings were at Lewis’s rooms at Magdalen College, Tuesday mornings at the Eagle and Child, a pub known to regulars as the Bird and Baby.

The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30), by Philip and Carol Zaleski, is a gutsy, glorious adoration of the English fantasy and faerie traditions, which celebrates what sometimes seems like a fantastical time when religion didn’t destroy art but created it. Tolkien, a philologist and professor of Anglo-Saxon, was Catholic; Lewis, a philosopher and tutor in English, was Anglican; Barfield, an Oxford alum, novelist, poet, dramatist, and solicitor, was a disciple of anthroposophy — a cult of self-cultivation that promised access to spiritual realms through meditation and eurhythmy; and Charles Williams, a novelist, poet, dramatist, and editor at Oxford University Press, worshipped women, through the rite of S&M. The Zaleskis are superb on the latter two. Barfield scandalized etymology by applying to language development the principles of evolutionary theory; changes in meaning, he argued, were indicative of changes in consciousness. Williams adapted the patristic doctrine of co-inherence — which defined the Trinity as simultaneously three and one, and reconciled Jesus’ divine and mortal selves — into a theology of love: men and women were condemned to suffer their individual freedoms until they ascended into couplehood and were redeemed.

Tolkien and Lewis need no introduction, only reintroduction. In the Zaleskis’ telling, both men lamented the lack of mythopoeic continuity between Britain’s pagan lore — much of it Irish, Scottish, and Welsh, most of it lost in the Norman conquest — and Christian scripture. The Lord of the Rings and the Chronicles of Narnia were attempts to establish foundational sagas for the Anglosphere, legends in which readers could reclaim both their own youths and the youth of their culture.

Other members of the Inklings included Lewis’s older brother Warren, the author of a massive social history of France under Louis XIV; the Chaucer scholar Nevill Coghill; the Victorianist David Cecil; and the Shakespeare authority Henry “Hugo” Dyson. The group’s founder was Edward Tangye Lean, who went on to serve as director of external broadcasting for the BBC during WWII. It was the previous war that united the club’s more senior members, however: Tolkien had barely crawled away from the Battle of the Somme, Lewis was wounded by his own troops in the Battle of Arras. The Zaleskis mention that of the 14,561 Oxford students who served in WWI, nearly 20 percent perished. Germany, whose aggressions bookended the Inklings’ heyday, was a formidable nemesis, even aesthetically: Tolkien’s interest in Norse gods and pilfered precious rings was decidedly not an interest in Aryan racial supremacy, and it became his lifework to ensure that the Anglo-Saxon spirit survived the perversions of the Nazi Mordor.

For the Inklings, this was the fundamental war: the heroic sagas and legends — whose heterodox strangeness was the mark of their antiquity, and whose antiquity compelled a belief in their symbolic truths — against the faithless forces of cynicism, literalism, and technology. The Inklings understood that victory depended on their readers resisting doubt and retaining the imaginative capacity for magic. Meanwhile, it would be their duty, as authors, not just to engage this childlike credulity but to sacralize it, by associating it with the happiest of endings — the soul’s salvation through Christ. For this, we turn to The Hobbit, chapter 19, verse 93:

And all the valley had become tilled again and rich, and the desolation was now filled with birds and blossoms in spring and fruit and feasting in autumn. And Lake-town was refounded and was more prosperous than ever, and much wealth went up and down the Running River; and there was friendship in those parts between elves and dwarves and men.