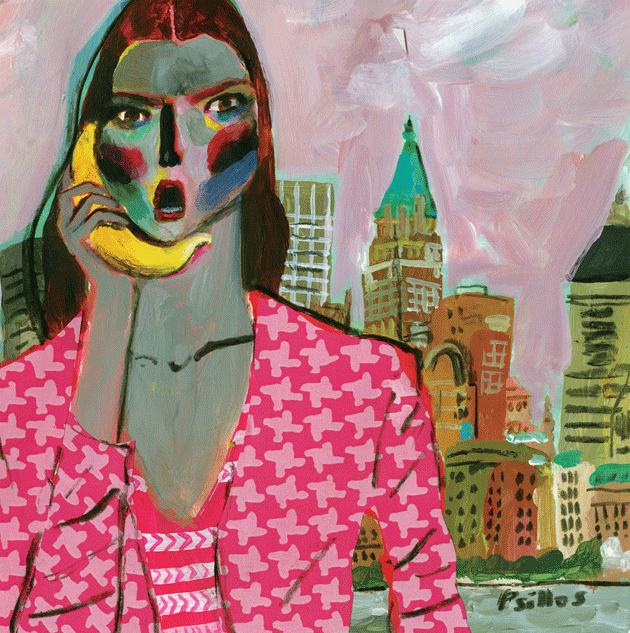

With the arrival of Tina Fey and Robert Carlock’s Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (Netflix), we finally have a major sitcom heroine whom we definitely don’t want to dress like. Kimmy Schmidt wears bright pinks, purples, and yellows. She looks, one character observes, like the wrapping of a Wendy’s old-fashioned hamburger. Albeit in a cute way. Sort of. She is a thirty-year-old woman who wears the clothes of a fifteen-year-old girl, and not a fifteen-year-old girl on television — there is a teenage character on Unbreakable, a Manhattan kid who wears black and flannel — but a fifteen-year-old girl from a small town in the Midwest. She looks like something out of the mail-order children’s-clothing catalogues of my Oklahoma childhood.

Kimmy is one of four Indiana women who have recently been freed after spending fifteen years imprisoned in an underground bunker by the Reverend Richard Wayne Gary Wayne. (The show’s ingenious opening-credit sequence — made to resemble a viral video — underlines the allusion to the Castro brothers in Ohio.) Kimmy, alone among the former captives, decides to leave Indiana, moving to New York to escape her notoriety as one of the “mole women.” (One of the other mole women, a Mexican immigrant, ends up making a living selling mole sauce.) The bunker concept usefully exaggerates the classic naïf-comes-to-the-big-city story line, but more importantly, and more unusually, it draws attention to Kimmy’s arrested development: she doesn’t just dress like a teenager; she is, emotionally and intellectually, still fifteen years old.

We are accustomed to seeing adult men act like boys — in an early episode, Kimmy’s love interest is shown in the middle of a video-game marathon, and this does not seem eccentrically juvenile. Meanwhile, one of the teenage girls on the show is having an affair with a married ophthalmologist, which seems maybe lamentable, but not remarkable. Kimmy, however, an adult with glitter sneakers and a backpack; Kimmy, an adult with the walls of her room painted lavender; Kimmy, an adult asking her boyfriend, “But what would the Care Bears say?” — this is straightforwardly repellent, funny, and disturbing. Comedy’s convex mirror makes visible the way that modern American teenage boys’ progress toward adulthood resembles Zeno’s paradox, while teenage girls are brought to adulthood abruptly, as if by jump cut; television, among its other powers, teaches them to want that.

The actress Ellie Kemper, who plays Kimmy, can pout like Mary Tyler Moore and wrinkle her nose like Elizabeth Montgomery in Bewitched. At moments she calls to mind Molly Ringwald in Sixteen Candles, and she briefly dates (and dumps) a man who resembles Mr. Big from Sex and the City. She also channels the hyperbolic cheerfulness of Barbara Eden in I Dream of Jeannie, and is that Kemper in a dinner-party scene, dressed up like a smoky-voiced dream of Ginger from Gilligan’s Island? I doubt I am the only possessor of a television-drenched childhood who sees these resonances.

Kemper is a fantastic physical comedian. Even a casual lean against a door that proves just a shade too far away — a move nearly as classic as a slip on a banana peel — is freshly hilarious, and surprisingly poignant, as Kimmy is the least at ease when trying to appear at ease in our world. (“Stop calling this the future,” her roommate says.) Still, with very little help, she quickly manages to find an apartment in New York, land and keep a job, study for the G.E.D., and make friends. She invites admiration, yet it will be a rare viewer who would want to trade places with her, even setting the matter of her wardrobe aside. That’s what makes her a more radical invention than most earlier female comic leads.

One possible exception is Roseanne Barr, though Barr’s show was concerned with family life, while Unbreakable is about women whose families are mostly absent. In the first episode, Kimmy meets Jacqueline, an Upper East Side housewife (played by Jane Krakowski) who hires her to be a nanny. Kimmy sees a painting of Jacqueline’s husband on the wall and asks, “Is that your reverend? Do you need help? Answer me honestly: Do you need help?” Jacqueline starts to cry. Later we see her holding an ice pack to her crotch after returning from the “gynodermatologist,” but she’s cheerful — she is expecting her husband to return after months away. At the opposite extreme of keptness is Kimmy’s loopy landlady, played by Carol Kane. She tells Titus, Kimmy’s roommate (played by Tituss Burgess), that she’s worried for his safety; she once knew a black man who was shot just for being black. It was her husband, and she was the one who shot him, maybe by accident, when he was coming back to bed, because, she says, New York in the Seventies was scary. There is a surprisingly glittering quality to dark moments like these, which appear unexpectedly and then don’t quite vanish.

The jokes that stayed with me the longest were the uncategorizable ones, even though they weren’t the ones that made me laugh at first. Kimmy keeps her history as a mole woman secret from most people, and at one point she lies about why she has no cell phone: she claims that a monkey at the zoo stole it. “Yeah, Xan,” she says to Jacqueline’s stepdaughter, and “the monkey was a woman: women can be anything these days.” At another moment, when Xan calls her a bitch, Kimmy says, “You mean a female dog? The thing that makes puppies?” It’s a weak comeback, and straight out of middle school — that’s part of the joke — but it’s also just weird.

Alongside the impossible-to-categorize category, there are jokes that are little more than transcriptions of our familiar, deranged world. Consider the scene in which Titus googles “mole women” and has to scroll past several women-held-captive stories before landing on Kimmy’s. Or the one in which Titus gets a job at a theme restaurant and discovers that he can hail a cab when he’s dressed as a werewolf but not when he’s out of costume. At Kimmy’s birthday party, Titus plays a song with the lyrics “I beat that bitch with a bat.” Kimmy gives him a querying look. He shrugs and says, “I can’t fix America.”

The longest-running of these jokes is the trial of the Reverend Richard Wayne Gary Wayne, which takes up much of the last three episodes of the season. The reverend represents himself at trial. He is good-looking, and holds the courtroom in thrall as he daisy-chains the nonsensical and the nonresponsive and the fear-inducing and the American flag. After Kimmy takes the witness stand and tells the reverend that she moved to New York, he addresses the jury: “The Big Apple . . . just like the one Eve gave to Adam. . . . If she had stayed in [Indiana] like a real American, I know for a fact all of you would be rich right now.” Everyone claps. The reverend’s confidence, savvy stupidity, and bold indifference to reality outshine logic and justice. “Oh my, he is wonderful,” Titus says, as he follows a livestream of the trial. “I mean, he’s a bad person, but he sure is watchable.”

And, of course, the media at the trial ask the mole women about what they are wearing: “Kathy Ireland for Family Dollar,” Kimmy’s best friend says. The women are losing.

Toward the end of the season, Kimmy meets her stepdad, who married her mother while Kimmy was in the bunker. He had been the detective in charge of finding the mole women, but as Kimmy puts it, “While I was missing, my mom married the guy who didn’t find me and then took off again.” In the final episode, we see him up in a tree with a cat that he has failed to rescue. “There’s another thing I’ve been meaning to ask you,” he says to the cat. “If a cat had a white stripe painted down its back, would a skunk really fall in love with it? No, right? I mean, I get why it’s funny; it just doesn’t sound real.”

Unbreakable is silly. It is absurd. It is, in so many places, implausible. For the first few episodes, I felt like I was watching a show aimed at, yes, fifteen-year-olds. But now I think that the cartoonishness is deliberate, a way to make vivid the bizarre ordinariness of girls and women who are somehow always the wrong age at the wrong time. It was Pepé Le Pew, after all, who made the tangle of wanted and unwanted amorous attention into a gag that even children could understand.

Le Pew was a contemporary of the fabulously funny women who starred in the screwball comedies of the 1940s. Things haven’t been quite as good for funny women onscreen since. Maybe there is a parallel golden moment developing now — though it’s hard to say, as there are so many more screens these days, and for every movie or show that’s better there’s one that’s Apatowly worse. But as a child, every afternoon I watched reruns of I Love Lucy, and mornings I woke up early to watch the 7:05 syndicated run of I Dream of Jeannie, followed by Bewitched at 7:35. It felt like a trance, but surely it was a training. My friends watched these shows, too; unintentionally we were educated by a procession of some of the best female comic leads in history.

For all their domestic submissiveness, the gorgeous blondes of my syndicated reruns were women of tremendous, and sometimes literally supernatural, power. The joke of Lucy trying to get into Ricky Ricardo’s show was a joke on real life: Desi Arnaz, who was discriminated against and whom no one wanted to hire, relied on Lucille Ball to get him onto her show. Does Tina Fey have the same powers? She wasn’t able to keep Unbreakable at NBC, even though the network had the rights. Liz Lemon, her character on 30 Rock, was more wholly lovable and admirable than Kimmy, and overall 30 Rock was a better show — both of which likely contributed to its seven-year run on NBC. Will Unbreakable have a similar run at Netflix? Kimmy is a darker invention than Liz, and the show, already virtuosically witty, may yet evolve into something stronger if it’s given time to grow up.