Julia Ward Howe published her first book of poetry on December 23, 1853, when she was thirty-four years old. It must have made a rather nice Christmas present for her husband, Samuel Gridley Howe, a distinguished doctor who had recently been rejected by the same press and who had no clue that his wife was shopping a manuscript of her own. And not just any manuscript: Passion-Flowers was an intensely personal airing of desires and grievances, the catalogue of a mutually unsatisfying union. The one that got everyone in Boston talking was “Mind Versus Mill-Stream,” in which a miller looking for a “mild, efficient brook” finds himself confronting an ungovernable and “perverse” river:

For men will woo the tempest,

And wed it, to their cost,

Then swear they took it for summer dew,

And ah! their peace is lost!

Subtle, no?

As Elaine Showalter’s excellent new biography, THE CIVIL WARS OF JULIA WARD HOWE (Simon & Schuster, $28), makes plain, the “apparent autobiographical nature and intellectual range” of Julia’s poetry was unusual for a time when most verses authored by women ran the gamut from simpering to sentimental. Passion-Flowers got some positive reviews — okay, Nathaniel Hawthorne did say that Julia “ought to have been soundly whipt for publishing” it — and sold out its first edition in a matter of weeks. Unsurprisingly, it proved less popular at home. Samuel — who went by Chev in homage to the Chevalier of the Order of St. Saviour that he was awarded for serving in the Greek war of independence, and who owned the plumed helmet Byron had taken to Missolonghi — was a handsome, domineering man eighteen years Julia’s senior. He issued two demands: that Julia revise the book for its second edition, and that she resume the marital relations that had been dormant for the previous eighteen months. Julia anticipated the birth of the resulting child, her fifth, in a letter to her sister: “My mental suffering during these nine months nearly past has been so great that I cannot be afraid of bodily torture. . . . I dread to see the face of my child, for I know I cannot love it.” This was not the only time that Julia conceived of motherhood as a punishment. She had referred to an earlier blessed event as “the unwelcome little unborn.”

On November 18, 1861, a parade that Julia was watching in northern Virginia was interrupted by a Confederate attack; that night, she wrote the poem that made her a celebrity, “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which put new words to the popular army song “John Brown’s Body.” (Chev had been a member of the Secret Six who funded Brown, though he later testified before the Senate that he had no knowledge of the plan to raid Harper’s Ferry.) Showalter argues that the “Battle Hymn” fused Julia’s feeling of domination by Chev with the Union cause: “During the Civil War, Julia understood that she was also fighting a domestic and personal civil war.” It’s a persuasive reading, but the phrase is icky, as if slavery and the oppression of women were fungible. What’s certain is that women made gains during the war because, as Julia herself wrote, they “found a new scope for their activities, and developed abilities hitherto unsuspected by themselves.” Her particular scope broadened to include the suffrage movement. In the 1880s, she campaigned for a bill that would guarantee widows half of their husband’s estate. She knew whereof she spoke: Chev, who died in 1876, had disinherited her.

Julia continued to write poetry, but none of it reached the heights of the “Battle Hymn,” or even “Mind Versus Mill-Stream.” She never got around to finishing the most interesting thing she started, a sensational novel about a hermaphrodite named Laurence that she drafted between 1846 and 1848. Showalter reads these fragments as an allegory of “the woman artist,” who is “not only a divided soul, but also a monster doomed to solitude and sorrow.” Solitude, however, was not Julia’s way. She wasn’t the kind of writer who scratched away in an attic room, holding out for posthumous glory; she was too busy organizing clubs and arranging speaking engagements. She wanted something more threatening to male power than mere artistic greatness — a public life. “I do not desire ecstatic, disembodied sainthood,” she wrote. “I would be human, and American, and a woman.”

In 1857, Julia read a bestseller that treated its subject in terms close to sainthood: Elizabeth Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë. “Charlotte Brontë is deeply interesting,” Julia wrote, “but I think she and I should not have liked each other, while still I see points of resemblance, many indeed, between us.” It’s a fair assessment: Brontë was not known to be especially likable. Intense, needy, morbidly shy, sensitive, awkward, sermonizing, and averse to dancing or games, she was dreadful at small talk and very ugly, with thinning hair and missing teeth, though she did have bright, intelligent eyes. What points of resemblance Julia saw are not entirely clear, but they probably had to do with feelings of thwartedness and confinement. She did not bother to read Jane Eyre, but if she had, the great Brontëan drama — the longing for a spirited male equal — would doubtless have resonated.

Mrs. Gaskell’s biography laid out the fundamentals of the Brontë myth that persists to our day — those feral children of the moors, dying one after the other under a brooding, distant father who paced the parsonage with a loaded gun. Claire Harman’s CHARLOTTE BRONTË: A FIERY HEART (Knopf, $30) is a fascinating, deeply researched study that resists the impulse to romanticize while still grappling with how strange and afflicted the Brontës really were. Charlotte was born in 1816 and lost her mother in 1821; three years later, she was sent to the grim Cowan Bridge school, the model for Jane Eyre’s Lowood and the place where her elder sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, caught tuberculosis and died.

From childhood well into their twenties, the four surviving Brontë siblings amused themselves by making up stories about imaginary worlds. Emily and Anne, the youngest, dreamed up Gondal, while Charlotte and her younger brother, Branwell, had Angria, whose denizens included the Duke of Wellington (Charlotte’s number-one crush) and the fictitious villain Northangerland. They bound these stories into booklets and magazines that were tiny in size but exceptional in word count, far surpassing their collective published output. Whatever was playful about the project turned dark and chaotic while Charlotte was teaching at Roe Head, a school eighteen miles from home, in the mid-1830s. In her journals she documented her panting visions of Angria, and her students described her writing in a trancelike state during class periods, covering the pages in cramped handwriting, her eyes closed all the while. Harman makes the interesting suggestion that such reveries might have been induced by opium. Charlotte denied ever trying laudanum drops when Mrs. Gaskell asked about it in 1853 — an odd claim, given their popularity and availability — but by that point Branwell had succumbed to addiction, and she may not have wanted to endorse the drug. At any rate, the strain of negotiating what Harman calls her “double life” led to a breakdown, and in 1838 Charlotte returned to the Haworth parsonage.

At times, A Fiery Heart reads like a warped bildungsroman in which the Brontë siblings, instead of moving from the country to the city, set out time and again to make their fortune — as governesses, teachers, or, in Branwell’s case, poet, painter, and railway booking clerk — only to wind up back home. In most families, daughters would have been expected to marry their way out of what was a serious economic dilemma. But no matter how desperate the situation became,

marriage seems to have been almost literally the last thing on the Brontë sisters’ minds. Spiritual communion, yes; love, sex, the sublime, yes; but the conventional female fate of marriage and motherhood does not appear either to have troubled or allured them much.

In her twenties, Charlotte turned down two proposals.

Eventually, a scheme was hatched for the girls to open a school of their own, and Charlotte and Emily went to Brussels to acquire the “finishing” necessary to attract pupils. The pensionnat in which they enrolled was run by the formidable Zoë Heger and her husband, Constantin, a French master who also taught at the boys academy next door and quickly became the love of Charlotte’s life. Heger was the model for Paul Emanuel in Villette, although “model” is too coy by half; he is the tempestuous, brilliant Paul, down to his manner and turns of phrase, and he’s also visible in the outlines of Rochester in Jane Eyre, and the Moore brothers in Shirley, and William Crimsworth in The Professor. It’s not what you’re thinking: “The union she craved with Heger was one of souls,” Harman writes. “Anything so paltry as a conventional friendship, anything as quotidian as adultery even, was clearly not in her mind.”

Emily, by many accounts the most gifted member of the Brontë family, required only the company of her dog, but it was Charlotte’s burden that she sought emotional companionship, intellectual exchange — in a word, recognition. (She was also the savviest about navigating the publishing world.) Heger was a dynamic, romantic figure, but even if he wasn’t her equal — who could have been? — she made him into a figure she could love.

My own theory about Charlotte is that the school essays she wrote for Heger in Brussels are the key to her oeuvre. She smuggled elements of the Angrian world into these compositions, which he taught her to revise, and then she imported the compositions into her novels. More at home in the “burning clime” of Angrian fantasy, she always struggled with realism, and the aggression and hatred that scholars typically point out in her work is, I think, the residue of this tussle with genre.

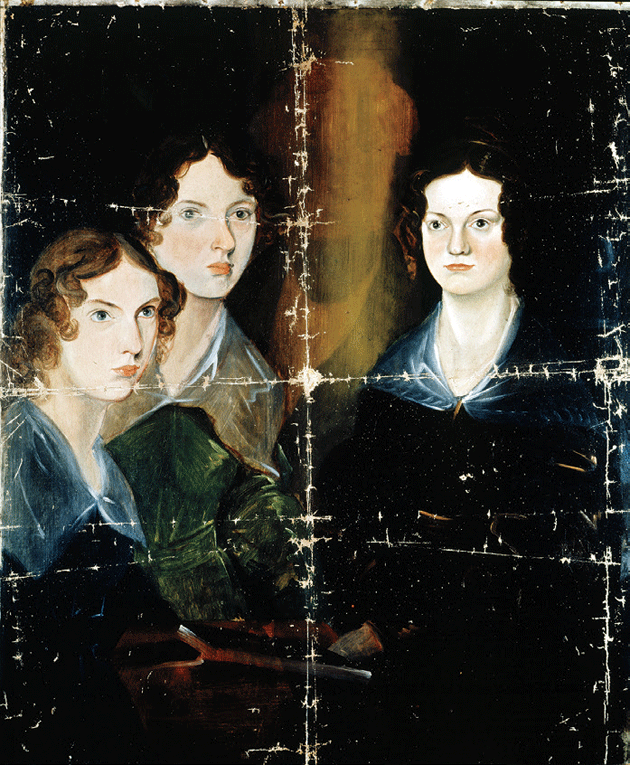

A portrait of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Bronte, by Branwell Bronte © Album/Art Resource, New York City

What Heger felt for Charlotte is hard to say; he certainly relished having such an eager student, and he gave her gifts, including a piece of wood from the crate that held Napoleon’s coffin — a fetish object for a Wellington partisan such as her. But there’s no denying that the attachment was lopsided. No letters from Heger to Charlotte survive. Four of what was presumably a barrage of hers were preserved by Zoë Heger, who planned to use them as evidence of Charlotte’s unhinged obsession, should any accusation of impropriety surface. One of these lingered on Heger’s desk long enough to serve as scratch paper. “Next to Charlotte’s pleas — ‘I am in a fever — I lose my appetite and my sleep — I pine away’ — he has noted the address of a cobbler.”

The sisters began publishing under the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell in 1846. It’s worth noting that Charlotte wrote Jane Eyre only after reading Emily’s Gothic Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, a roman à clef about being a governess. (It is cruelly ironic that the critics called Agnes Grey a weak imitation of Jane Eyre — Anne always was the most overlooked.) Contemporary readers may not immediately grasp how bold and strange Charlotte’s novels were. In everyday travesties — disgusting boarding-school food, corporal punishment, women frittering their lives away waiting to be married off — she saw matters of thundering, soul-destroying injustice. This led to accusations of rabble-rousing. The Christian Remembrancer charged Jane Eyre with “moral Jacobinism” and The Quarterly Review called it dangerously Chartist, but Charlotte’s rebellion was spiritual; her desire was for submission to a worthy hand, not class warfare. (Like her father, she was both sympathetic to and alarmed by local labor uprisings.) Although her themes always involve the disciplining of raging passion, she took almost no edits from her publishers. Her novels are, technically, disasters. They open on scenes that have little or no bearing on the main plot; they are hectoring and digressive, pausing often to prophesy or address the reader directly; they indulge in impossible disguises, double identities, and absurd reveals. They are out of control in a way comparable only to Melville or Dostoevsky. But while their action is alternately bizarre and plodding, they are subjectively acute; Villette, Harman writes, reached “psychological depths never attempted in fiction before.”

A Fiery Heart concludes with — what else? — a marriage, and the triumph of the long-suffering local curate Arthur Bell Nicholls, who waited seven years to declare himself. He had a second-rate mind — “I cannot conceal from myself that he is not intellectual,” Charlotte said — but she grew to love him, albeit briefly. She died nine months after they married, at the age of thirty-eight. It has long been thought that consumption killed her, but Harman blames a severe reaction to pregnancy hormones. There is the tantalizing possibility that if Mrs. Gaskell had known of Charlotte’s troubles she might have helped: “I do fancy that if I had come, I could have induced her,” she wrote, “to do what was so absolutely necessary for her very life”: i.e., an abortion. It is tempting to conclude that domesticity itself murdered Charlotte Brontë, but of course, to do so only perpetuates a different myth — that of the female genius doomed to unhappy solitude, the madwoman aflame.