Discussed in this essay:

Gone with the Mind, by Mark Leyner. Little, Brown. 256 pages. $25.

Gone with the Mind, Mark Leyner’s seventh book of fiction, might seem like a high-spirited satiric romp if you haven’t read the other six. It is the transcript of a fictitious reading delivered by a fictitious writer named Mark Leyner as part of the Non-fiction at the Food Court Reading Series at the Woodcreek Plaza Mall. Mark, who has come to the mall to read excerpts from his new memoir, also entitled “Gone with the Mind,” is introduced by his mother. Her introduction is forty pages long; it commences with her description of the crippling morning sickness she suffered when Mark was in utero. The number of people in attendance at the reading, it is important to note, is zero; two workers, from Sbarro and Panda Express, are technically seated in the food court, but they are on break, and they resist all attempts by Leyner mère and fils to get them to look up from their phones and pretend to be a legit audience.

Mark means to preface his reading with a few remarks about the genesis of “Gone with the Mind”; it becomes clear after a while that the reading proper is probably never going to begin — that Mark, standing atop a plastic table in order to be better seen and heard (at least in theory), will do pretty much anything to keep the meta-narcissistic experience of talking about writing about himself from coming to an end. (His mother, the only one listening, reassures him periodically that he’s doing great and that she could listen to him indefinitely.) “Just a little background before I get started,” he says:

Gone with the Mind was originally going to be an autobiography in the form of a first-person shooter/flight-simulator game. . . . The, uh . . . the goal of the game is to successfully reach my mother’s womb, in which I attempt to unravel or unzip my father’s and mother’s DNA in the zygote, which will free me of having to eternally repeat this life.

Though the novel we’re reading does, in a very loose fashion, describe how the “Gone with the Mind” project morphed from this idea — with the collaboration, Mark insists, of a key, hallucinatory figure known as the Imaginary Intern — into the memoir from which he is nominally about to read, it has little resemblance, and even less aspiration, to what might conventionally be called a story. Mark makes plenty clear his revulsion toward any “rigid chronology of pivotal incidents,” at one point advocating the replacement of “incumbent imperial narratives” with a new artistic medium based entirely on smell. What we get in lieu of such a chronology is a long, associative series of memories, digressions, and musings, some about Mark’s own life (mostly identical to that of his author, from the Jersey City childhood to the actual name of the Manhattan doctor who performed his robotic prostatectomy) and others on subjects ranging from Mussolini to a proposed reality-TV show about self-endoscopy to a recent article in a scientific journal: “South Korean Microbiologist Discovers That Even Amoebae Fall into the Five Basic Archetypal Categories: Nerd, Bully, Hot, Dumpy, and New Kid.”

The word “riff” sometimes seems pejorative in a literary context, but it’s hard to avoid here — not for reasons having to do with jazzlike improvisational skill, but simply because Leyner is very funny. While anecdotal experience in getting people to agree with me on this point suggests a certain gender divide, I will assert nevertheless that he’s as funny as any writer I could name. His frame of reference, within the space of a paragraph, or even a sentence, is dizzying. (He was once called “the poet laureate of information overload.”) He gets a great deal of mileage out of the names of things. Sometimes it’s a familiar high-low move, as when he refers in passing to “a group of experts” consisting of Alan Greenspan, Dog the Bounty Hunter, and “controversial Beverly Hills plastic surgeon Dr. Giancarlo Capella.” More often, though, it’s his specificity with obscure common nouns, and his establishment of a Buster Keaton–style deadpan through his fastidious verbal exactitude. Most writers would have stopped this sentence eleven words sooner:

And I tend to believe that this inclination to look back on one’s life and superimpose a teleological narrative of cause and effect is probably itself a symptom of incipient dementia, caused by some prion disease or the clumping of beta-amyloid plaques.

Or spot the Leyneresque word near the end of this sentence about the Imaginary Intern:

Life’s a harrowing fucking slog — we’re driven by irrational, atavistic impulses into an unfathomable void of quantum indeterminacy — but, still . . . it’s nice to have a friend, a comrade, a paracosm, whatever, to share things with.

He is, to pick the kind of arcane cultural referent he might enjoy, the Alexander Popov of comic fiction: not renowned for endurance but unbeatable in a sprint. “If it weren’t for Internet porn,” he apologizes to his “audience” at one point, “I’m sure we would have finished Gone with the Mind a lot sooner. If it weren’t for Internet porn, there’d be a cure for cancer, there’d be human photosynthesis, levitation, time travel, everything.”

In the aggregate, Gone with the Mind’s uninterrupted associative riffing resembles narration, or even stand-up comedy, much less than it does psychotherapy. Mark has been prompted — it scarcely matters how — to start talking about how he came to be the fifty-eight-year-old son, husband, father, and writer he is today; as with any venture into talk therapy, maybe something comes of it, maybe not. The mountainous exercise in narcissism that is this “reading” is of course dramatically undercut by the fact that no one is listening, that no one (with the exception of Mark’s mother) cares, and that it requires a heroic effort of magical thinking on Mark’s part to keep this awareness of his own insignificance at bay. It also requires that he not stop talking. Gone with the Mind is a triumph of the will: it’s as funny as Lucky’s monologue in Waiting for Godot, and as horrifying. Mark has to work really, really hard — tragically hard — to maintain the fiction not simply that he is a public figure but that he exists at all. You get the sense that if his mother weren’t there, he would disappear.

It’s not easy to think of another contemporary literary career with which Leyner’s might be fairly compared. He was and is considered a prophetic satirist of various unflattering aspects of our age: the obsession with fame, the focus on self-aggrandizement, the lightning-fast yet meaningless connectivity of the search engine, the memoir and reality-TV boom, even autofiction. (The “poetic I” constructed so subtly in the work of Ben Lerner and Rachel Cusk is, in Leyner’s hands, blown up to the proportions of a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon.) By the time he published Et Tu, Babe, his third book (and first novel), in 1992, he had begun to build his fictions around a magnificently exaggerated, grotesquely famous and powerful version of himself. Other novelists (Martin Amis, Philip Roth) had played similar identity games, just as other writers (Thomas Bernhard, Gordon Lish) had explored the medium of the riff, the rant, the endless digressive introduction to a story that never gets told. Leyner’s marriage of these techniques in the service of broad intellectual comedy hit the zeitgeist square in its sweet spot.

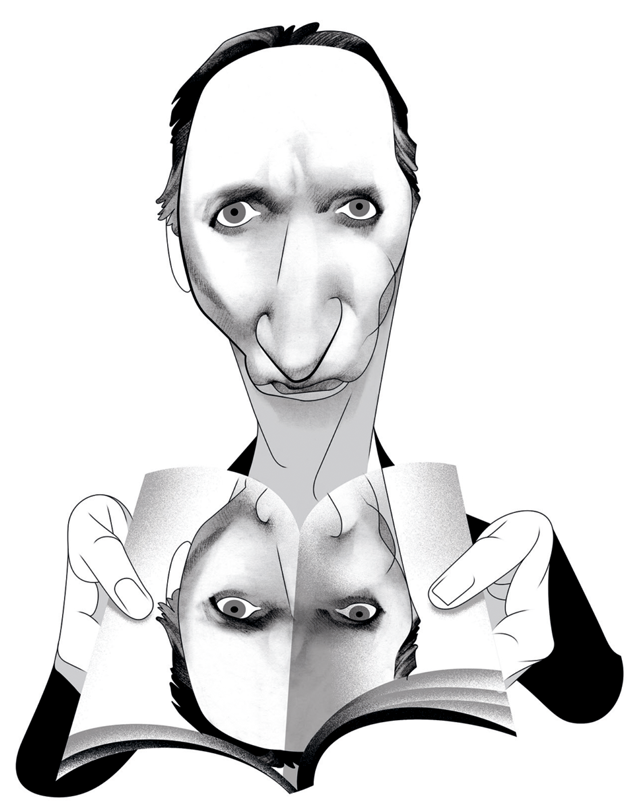

You can still find on YouTube a 1996 episode of Charlie Rose devoted to “The Future of Fiction in the Information Age,” whose three participants are David Foster Wallace, Jonathan Franzen, and Leyner. (So high has Wallace’s star risen in the intervening twenty years that one of the first facts some people now recall about Leyner is that he’s the writer Wallace once called “a kind of antichrist.”) The New York Times Magazine ran a cover story about Leyner. He wrote monthly columns in Esquire and the late George magazine. His origins as a member of an avant-garde artistic coalition called the Fiction Collective notwithstanding, his novels and story collections became wildly popular, until, in as sure a sign of shark-jumping as exists in the world of literary fiction, new editions of his work began to feature his photograph on the front cover.

Yet there seemed something paradoxically modest about his always making “Mark Leyner” the largest and crudest and most egocentric figure in his work, offering up his own persona as a kind of lamb to the satire. In Et Tu, Babe, that persona lives inside the heavily fortified Leyner HQ, surrounded by an army of toadies known as Team Leyner and protected against constant assassination attempts by an elite corps of cyborgs. Occasionally he takes time off to teach writing workshops, in which he singles out the most promising students and has them killed. In Tooth Imprints on a Corn Dog (1995), Mark Leyner shops for a $3,450 Armani backpack for his daughter’s Haute Barbie, and sequesters himself, Belushi-like, in the Chateau Marmont, in order to compose a thousand lines of free verse on deadline for a German magazine. In The Tetherballs of Bougainville (1997), a thirteen-year-old Mark seduces the zaftig warden bent on executing his father, offers his consulting services to a grateful foreign dictator, and creates a hit TV show called America’s Funniest Violations of Psychiatrist/Patient Confidentiality. Thus did Leyner mock his own desire for fame even as he worked hard to maintain it. Inevitably, perhaps, his commitment to this monstrous version of himself began to seem a little like shtick; still, by the end of the millennium Leyner had as high a profile as any fiction writer in America. And then he vanished.

Well, okay, he didn’t vanish; he stopped writing fiction. He went to Hollywood, where, in fifteen or so years, his only credit was as a cowriter of a 2008 John Cusack movie called War, Inc. He also, bizarrely, cowrote with a doctor friend a best-selling series of answers to laypeople’s medical questions, one volume of which was distinctively titled Why Do Men Have Nipples? In an interview, he said this about his long hiatus:

I was on Letterman. I read from one of my books on Conan. I almost lost my place, thinking, How fucking great is this? You’re reading from one of your books on television. But I would also think, Why did I ever even want this? I’d just rather be home. We wouldn’t do what we do if we loved being with people. We like to be by ourselves.

There’s something a little boilerplate about that, though, something too pat to account for Leyner’s own pathology. In his twentieth-century work there was always a naked eagerness to entertain; in retrospect, it seems like what he was really satirizing, or co-opting, or purging from himself, in his outsized portrayals of a world wherein he was worshipped like a god, may have been his actual need to know that we liked him. As anyone who fits that sort of psychological profile might recognize, the maintenance of success is so demanding that it almost inevitably generates fantasies of failure. Maybe the tension that he was opting out of by ceasing to write stories about “Mark Leyner” — by retreating into a kind of authorship where his identity was submerged (I don’t remember a lot of War, Inc. posters with his face on them) — was more interior: less about the war between the heroically solitary artist and the culture that demands things from him than about the war between his own impulses.

In 2012, Leyner returned to literary fiction with a novel called The Sugar Frosted Nutsack. As in Gone with the Mind, the entirety of the novel — whose central character is not Mark Leyner but an unemployed butcher from New Jersey named Ike Karton — consists of a digressive ramp-up to a hypothetical epic that never actually begins. But the discontinuity of those digressions — the discontinuity between individual sentences, sometimes — is so aggressive as to feel almost hostile. Though the book has many champions to whom attention must be paid (Sam Lipsyte, Rick Moody, Ben Marcus), I confess I find it nearly unreadable. And while unreadability was probably not the precise effect Leyner was going for, it’s not as far off as you might think.

In an interview conducted by Moody that was appended to the paperback edition of Nutsack, Leyner mentioned his affinity for Antonin Artaud, the founder of the Theatre of Cruelty — this just after he has said, “I have always thought of what I do as an enormous act of generosity. . . . My impulse is just to give the reader enormous pleasure.” Conceiving of one’s art as a generous attempt to provide pleasure might seem at first blush a little hard to square with the confrontational views of Artaud, who professed that “no one has ever written, painted, sculpted, modeled, built, or invented except literally to get out of hell.” Still, wanting to assault one’s audience and needing reassurances of its love at the same time: if that’s the tension The Sugar Frosted Nutsack fails to reconcile, it’s also, in its very irreconcilability, an interesting lens through which to view both Leyner’s early work and his decision to stop producing it.

“Yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi,” Mark reminisces at one point in Gone with the Mind, quoting a motto from Japanese manga: “No climax, no resolution, no meaning. Because, I have to say, even then, at eight years of age, every other kind of writing struck me as banal and outdated, and just boring beyond endurance.” He says this, of course, to an empty food court, to an audience that is not there.

The conflict in Leyner’s work between the desire to please and the desire to alienate has always had heavily Freudian undertones. Gone with the Mind plays those undertones loud and proud, not only in the absurdity of its premise (the son, now fifty-eight, standing on a table and putting on a show for his admiring mother) but, more sadly and self-consciously, in Mark’s own narration:

Like the preening narcissism of so many physically repulsive men, nothing matches the overweening, magisterial pride of the abject failure, the son manqué. Freud said: “A man who has been the indisputable favorite of his mother keeps for life the feeling of a conqueror.” And I believe this remains especially true for the son who has clearly demonstrated that he’s capable of accomplishing absolutely nothing.

Elsewhere Mark refers to himself as “the eternal little man, inflated with dreams of flamboyant success but forced back on his own futility,” and, with an extra knife twist at the end, “Oh sad, sad, Ferbered prince . . . sad, sad, Ferbered, oedipally conflicted, impotent prince and poseur . . . ever posing autobiographically as yourself.”

Even when — especially when — the real-life Mark Leyner was at his most famous, we never quite got what he was doing. We thought he was satirizing us, but maybe the thing that he was mocking was never really outside him. Though of course Mark never gets around to reading the reputedly brilliant ending of “Gone with the Mind” — an ending so ingenious as to represent “an astonishing victory over the forces of ‘storytelling,’ the decadent pastime of white-guard counterrevolutionaries” — we are, as in Mark’s original video-game conceit, repeatedly reminded of the longing to begin:

There was a golden age for me when it was just my mother and myself, and this is still the idealized world I long for, still the mythic, primordial time, the paradisiacal status quo ante that I persistently hearken back to, whose restoration is at the core of a mystico-fascistic politics.

Gone with the Mind scarcely resembles the sort of conventional novel for which both Mark and Leyner share a principled artistic revulsion, but it’s as close as they’re likely to come, in that it embodies, and is driven by, a conventionally dramatic idea, that of tension between opposites. That tension — in the words of Leyner’s War, Inc. cowriter, “The fundamental preposterousness of being a writer or even a person. That feeling that you have to be the best in the world, versus the terror that you are nothing and you are no one” — convincingly generates the emotional element one might once have voted Least Likely to Appear in a Mark Leyner Novel: pathos.