We conventionally use the period to punctuate a finished thought. But Rosmarie Waldrop, one of the most innovative poets in English, deploys the period as a rest, often musical, in which potential meanings multiply. The periods in her prose poems function like the line breaks in verse. This makes her work a powerful mixture of directness and disjunction: she conveys information at one moment only to shatter the method of conveyance at the next. A period that seems at first to indicate closure turns out to have opened a silence within a single thought. Or established an unbridgeable gulf between disparate thoughts. In Waldrop’s hands, a period is not the sign of authority but a tiny black hole within its logic.

In the magnificent sequence that follows, published here for the first time, Waldrop’s experiments with the period (in the grammatical sense) are brought to bear on an experimental period (in the epochal sense): the Weimar Republic, 1919–33, a time of feverish activity in the arts. It is the time, perhaps most famously, of Dada, which originated in Zurich in 1916 but was soon thereafter flourishing in Berlin — if one can speak of a movement opposed to everything as “flourishing”; if one can speak of “flourishing” when one can hear, as Waldrop puts it, “the approach of jackboots.”

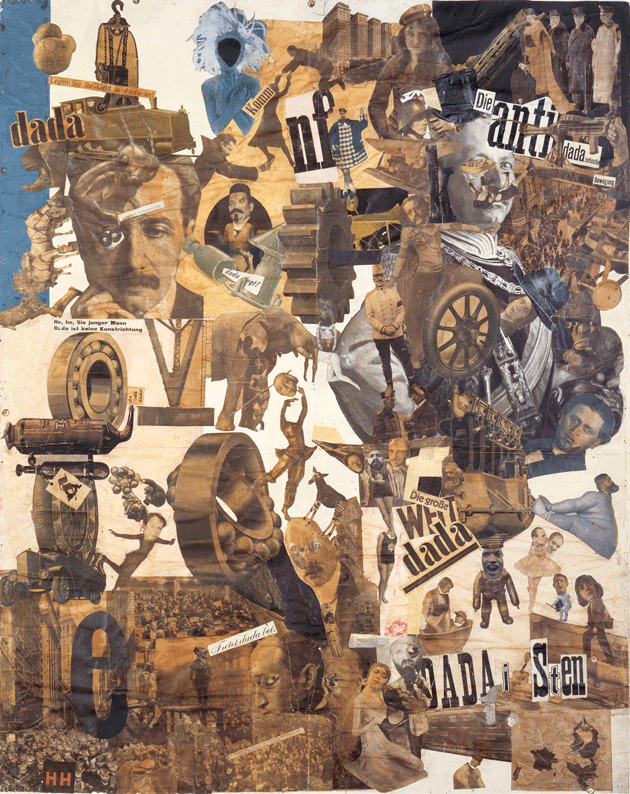

Waldrop takes her title from Hannah Höch’s 1919 photomontage Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany. Höch’s composition is, among many other things, a send-up of the most powerful men of the day — political figures such as Kaiser Wilhelm and leading men of Dada such as George Grosz and Wieland Herzfelde. Höch’s work is an indictment of machismo outside and inside the arts, her kitchen knife a domestic implement cutting up and cutting down these cultivated images of masculinity. The male Dadaists, despite opposing the beer-belly values of the bourgeoisie, were quite capable of reproducing them. Indeed, the Dadaist Hans Richter said that Höch’s greatest contribution to Dada was “the sandwiches, beer, and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money.”

Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, by Hannah Höch © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City/bpk, Berlin/Art Resource, New York City

Waldrop, née Sebald, was born in 1935 in Kitzingen, and emigrated to the United States in 1958. In this poem, one major German collage artist is addressing another on the level of technique: Waldrop explores the interwar period, Höch’s particular circumstances, and the artist’s famous composition. Her mysterious-sounding line — “… the word Dada emanates from Einstein’s head, clouds lined in black” — is a direct reading of Höch’s piece. Waldrop cuts up and rejoins her sources, repurposing found language (and what other kind of language is there, really) to startling effect. She draws from Maud Lavin’s book on Höch, from the poet Suzanne Doppelt, and fragments from works including Alfred North Whitehead’s Process and Reality (1929) and Wallace Stevens’s Harmonium (1923).

The Höch photomontage contains a small self-portrait, and I can’t help but wonder to what degree Waldrop is here reflecting on her own practice, her own gender and Germanness, as they relate to her art. In what sense is she reconsidering her origins and her relationship with the historical avant-garde? Is an analogy being drawn between 1919 and 2016, a conjunction of two periods?

Cut With the Kitchen Knife

1.

Despite dramatic changes in women’s status. During the Weimar Republic. Their economic situation did not improve. Hannah Höch was thrown into the sharp indifference of the city. While the eye swivels, endlessly, to recognize the January sun as sun. The artist is concerned with appropriating the dead. The objective immortality of fact. (The way you fish a pickle out of a jar?) Some nights are not as dark as the soul, though the days will become darker. Pictures, pennies, paper. Faith in reason is not a premise: it’s an ideal seeking satisfaction. Like freedom, movement, sexual pleasure, Dada, revolution.

2.

One must have thoughts cut with the kitchen knife. By Hannah Höch. To see the body dissected into its restless multiplicity. And the world in brittle winter light, high toward the cold. Compare pulled out of school to care for a fourth sibling. With art, later, pulled out of galleries, the artist into lying low. For now her eye follows its own method: vertigo. Indivisible sensations. Wheels, gears, ball bearings. Clouds are massing, and we cannot account for them. By the sea’s evaporation. Though we’ve failed to find any elements that don’t conform to general theory.

3.

Sight presumes fissure. Just as language. Is elliptical and requires leaps. But few philosophers admit that our ideas are feelings. World War I stops an art student from traveling to Paris, not from Red Cross work or being a Dadaist’s lover. Difficult apprenticeships. Rather than a pinhole for objective reproduction of the world: violent juxtaposition. Of metal and flesh. Antagonistic equivalence, kaleidoscopic, centrifugal. Over deposed Kaiser Wilhelm’s left shoulder, people. Who have been cold a long time in line. At the employment office.

4.

Clips images from print media as a way of seeing form. Montages with a disorienting variety of perspective. Variation in scale, interruption of contours. And rough, visible seams to see closer to touch. This will be called entartet. The telephone brims with signals. Breath rises white like fog. Though Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch try to embody the New Man and New Woman. The tolerance of flesh gets lost in the old gender roles. With wind sweeping the streets. Windows, wires, tinder. There must be limits to the claim that all elements can be explained.

5.

The deep of the world fills the eyes. With tears. Then to see thought there is need. To speak aloud into the ears. Always, in the real world, the brute fact. Hunger, misery, the chill of winter. The sound of boots marching. But who is the dancer who tickles Kaiser Wilhelm’s chin? Why is her head replaced? By Hindenburg’s? There is dispute if creative ferment will lead to religion, the internal combustion engine, or National Socialism. But our object of veneration is now orgasm.

6.

A naked body connects directly. Dada Evenings, Dada Fairs, Dada Exhibitions. Unthinkable some years later. Hannah sees unfettered freedom with one eye larger than the other. As if through Hausmann’s monocle. As when the dark upon the face of the deep gave way to forms. Unfurled sky, a bug, arrow, paintbrush, scissors, ball of wool. Philosophy can only introduce us to subject/predicate, substance/quality, particular/universal. But reality is. Except for the rent. A matter of fine-tuning. An excited condition of the retina.

7.

Panic breaks out at the barbershops: German women hold elected office. Nipple, bud, eyelash, comma. They walk a high wire. The men hope, right into the Baltic. And that the wind lift up dresses and show the blindness of flesh. That Hannah’s role remain making coffee. Do we still expect space to be homogeneous, as seen by an intelligence without body? And that perceiving an actual being objectifies her into data? The fully clothed feeling of satisfaction. Could a bodiless intelligence drive a horseless carriage? Or does satisfaction blanket all additions?

8.

It is winter. The pine trees crusted with snow, and the air tense with wires. Hannah’s photomontages respond to the shifting representations of the New Woman: Dancers, actresses, Marx, Lenin, and other revolutionary figures. In color. Which is itself a degree of darkness and will veer to brown. (Shirts.) What light there is travels in waves. What isn’t clear is the sudden turns. A paper airplane takes from one direction to another. Or public opinion. Or that art should embody the adventure of hope.

9.

The way Hannah juxtaposes. Athletes’ and dancers’ bodies with piles of machinery, cogwheels, soldiers. Hooks the pleasure principle to the moment it crashes. Into reality. You’d better look from the corner of your eye. Bank, dime store, orphanage. Or with the eyes at the end of your fingers. Then doubt evaporates so that a complete feeling. In regard to the universe, thinks Hannah. Will bring about a transformation of the heart. In spite of the temperature. And murderous militias.

10.

The dominant emotion. In Depression-era Germany was anger. What happens if it couples with the pleasure of nostalgia? A gleam shagged with flags and tending toward violence. The initial fact (anger) is macrocosmic in the sense of being relevant to all occasions. Work, no work, funeral home. The horizon takes on considerable weight, as it does before disasters. And paralyzes our feelings. The view so abstract it might not exist. The words snow is falling are spit like a curse. At snow falling. On bicycles and BMWs.

11.

In the center, the dancer Niddy Impekoven’s body. Kicks montage into motion across the wall between pure art and pop culture. Muskets and watermarks. Why is she decapitated? Anticipating the coming atrocities? Her arms reach for Käthe Kollwitz’s head that floats away at a diagonal. Head expressionless except for its name. Which, like Hannah’s, will become suspect. The eye sits like a spider at the center of its nerves. Is it true that the final fact is always microscopic? Peculiar to the specific occasion, e.g., leaving Raoul Hausmann? A foreclosure that stirs the heart?

12.

It is difficult to know if representation of pleasure will, through desire, motivate change. The body always relevant. An optical stimulus and perhaps lovely. Perspective on clothes and bones. Gustav Fechner damaged his eyesight by staring into the sun in the course of research. On afterimages. A piercing realization that vision is corporeal. Then does it need to refer to the cups and saucers outside it? Sometimes Hannah does a little two-step. While philosophy knows only solitary substances, her world is buzzing with fellow creatures. Unlike some years later. When you don’t dare speak to a neighbor.

13.

A grid format implied by vertical strips of paper. Disrupted by diagonals. And the eye, unable to stand still for you to look into. Goes out of the frame to open other horizons. Where the speed of light flashes in all directions. Snow has covered. The most normative behavior along with the museums. On a good day, as the eye so the object. At other times Hannah’s heart is heavy. Because she feels the approach of jackboots? The subject/predicate habit of thought doesn’t admit that facts are in the world like garbage trucks rolling down the street. Or tanks.

14.

With high and happy tension Hannah. Makes at least two glossy magazines overflow on the facts. Kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness. She scissors a grand jeté across. Up down right left high low. Escaping from the ordinary she annexes what little hope there still is. (Though the water pipes have frozen and burst.) And reveals the complicity. Of metaphysics and perspective. Each exterior thing is a nexus of occasions whereas no person steps twice. On the same sidewalk. No person, in a few years, escapes suspicion.

15.

A utopian light captures. Edges of technology and blots out the defense minister and his Freikorps assassins. River, sluice, wall, poplar. Then reality is passage. From one gigantic montage to another by simple rotation. Space comes and goes as in a movie. And the New Woman unfurls her body from right to left. Inviting even the dead to new life. But time is a component of observation. There is a darkness. That seems to grow deeper. Right before our eyes.

16.

No chronicle (of the Weimar years) fails to note. The sensation of speeded-up life and the latest Charlie Chaplin. Machines vibrate in all their parts. Wind from the east passes through windows. And other openings. Streetlights striate the night. Which is large. And hides more knives than condoms. Knowledge is founded on particular things, but there are too many. Rows upon rows of eyeglasses. Not sufficient to reveal the shape of horror.

17.

Hannah eyes beer-bellies to portray Weimar politicians. Recklessness and wintry trees. A mirror to our thinking and all its deformities. While the word Dada emanates from Einstein’s head, clouds lined in black. Already mourn the next generation. Driving all thought indoors, denying external referents. The eye is a better witness than the ear. Especially in daylight when it beholds. Nothing that is not there. When the meaning of “thing” is potential. For process. And fear spreads like the flu across the entire country.

18.

So powerful. The flood of images. It could sweep the dark night of the soul to distant galaxies. Hannah signs her name in order. Not to lose it. Among dreary woolens and other afflictions. In spite of actuality being incurably atomic, her eyes. Are panoramic like a frog’s. She shivers. Because of winter? Of night and fog? Or because she’s told: be careful what you see?