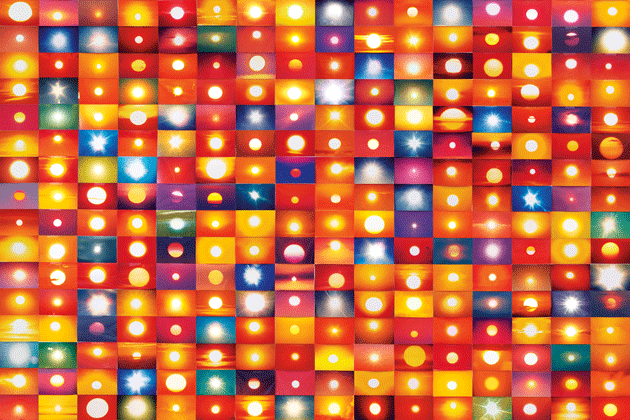

Right now someone is taking a picture of a sunset. It could be on a beach in Barbados or above the Arctic Circle or on a motel balcony in Seattle. And that person is not alone. Thousands of people are taking exactly the same picture. No need to search for them; Penelope Umbrico has already done that. A photo-based artist, Umbrico has compiled thousands of images from the social-media site Flickr. She exhibits collections of them, each photograph tightly cropped to reveal only the sun. Seeing one of her wall-size installations forces us to confront the question: Why are we taking all these pictures? For a photographer, however, the more pressing question is: Are there any pictures left to take?

“541795 Suns from Sunsets from Flickr (Partial) 01/26/06” (detail), by Penelope Umbrico Courtesy the artist; Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York City; and Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, California

Oliver Wendell Holmes said that every photograph somehow peels a bit of the surface off the world and fixes it in time. If that were true, the surface would be pretty thin by now. In 2014, an estimated 800 billion photographs were taken worldwide. Of course, Holmes was writing in the middle of the nineteenth century, when photography was special, revolutionary; William Henry Fox Talbot, who invented two of the earliest photographic processes, called the photograph “a little bit of magic realized.”

Photography quickly became almost as popular as it is now, at least among those who could afford a camera. In 1853, more than 3 million daguerreotypes were produced in the United States alone. This is quite remarkable for a method that was cumbersome, toxic, and, because of the need for silver-coated copper plates, expensive. (By 1865, daguerreotypes had been abandoned in favor of easier, cheaper alternatives.) Cartoonists of the time lampooned the craze in almost the same terms that their modern counterparts satirize the proliferation of selfies. Society, it seems, has been obsessed with photography since minute one.

It is not only the volume of photographs that has changed, but also, and perhaps more importantly, the ease with which they are shared. The impact that this has had — and continues to have — on social behavior has led to much hand-wringing about narcissism, isolation, and the inappropriate disclosure of personal data. The influence of social photography on artistic photography has been equally profound. Umbrico and other artists whose practices are based on photographic appropriation take this social behavior as their immediate subject. Why so many sunsets?

“Crescent Eyed Portrait (in Blue),” by Daniel Gordon, whose monograph Still Lifes, Portraits, and

Parts was published by Mörel Books.

Umbrico’s installations tell us something about what people want to broadcast, what they want to remember, and perhaps also what they want to tame. Associations of twilight, romance, mortality, and self-reflection in the face of nature’s immensity — however these might be trivialized by advertising — are present in these images. A residual sublimity may explain why so many visitors to Umbrico’s exhibitions take selfies in front of her sunsets.

Other photo-based artists — Kate Steciw and Daniel Gordon prominent among them — have focused on the collage nature of the visual reality encountered online. Advertisements, atrocities, stupid pet jokes, selfies, and pornography flash across our screens without spatial or temporal context, barely under our control. These artists sift through the images that haphazardly appear on our devices, and combine them with their own photographs. Steciw amasses a visual archive by performing Internet searches, loosely guided by an associative logic, and compiles the pictures she finds into a single, densely layered image. Gordon composes portraits out of fragments, an eye from here, a nose from there, like visual ransom notes. Both artists create order from the chaos by fixing its fragments in layered relation, happy to let the seams show. They encourage viewers to reflect on the emotional, economic, and political impacts of what Susan Sontag long ago called our “image-choked world.”

Within this rising tide, the power of any individual image or group of images to move or enlighten us would seem to be almost nil. Taking a picture not just to capture a moment but to frame an experience for contemplation (what Nathan Jurgenson, a sociologist and media theorist, calls the “atomizing of the ephemeral flow”) makes even less sense. Haven’t all the pictures already been taken? Is there any image that has not already become a cliché? That is the challenge facing a generation of young photographers raised on social media and seeking to produce something more lasting than disposable fodder for Snapchat.

“Construction 143,” by Kate Steciw, whose work was on view in May at Brand New Gallery, in Milan. Courtesy the artist and Brand New Gallery, Milan

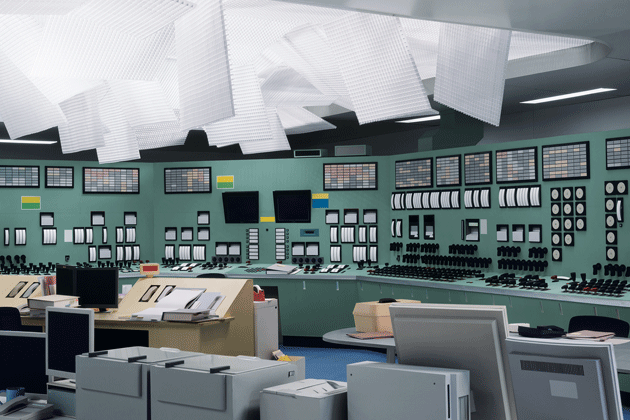

What they are up against is exemplified by the recent work of Thomas Demand, who has immersed himself in the problem of photography after all the pictures have been taken in a series titled Dailies, based on his own cell-phone pictures. Nothing would seem to be further from his usual interests. Demand studied at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, a school known for training photographers such as Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky, who work in large-format color photography — perhaps the medium’s least spontaneous, least casual form. Demand, who is in his fifties, has developed a distinctive approach, drawing on his training as a sculptor. Working from images circulating in mass media, he creates large-scale paper models of scenes, and then photographs the models in color and with a large-format camera. The models, which are destroyed after the photos are taken, usually depict the setting of some traumatic or decisive event — a kitchen used by Saddam Hussein, the control room of the Fukushima nuclear plant after the meltdown — but they are deliberately devoid of details, making the locations appear almost dreamlike, vaguely familiar but difficult to identify. It’s as if Demand were probing our cultural unconscious. How personal and particular are the memories we think belong to us, and how much secondhand experience have we absorbed by osmosis?

“Control Room,” by Thomas Demand, whose work is on view at the Modern Art Museum of Forth Worth, in Texas © The artist/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York City

The photographs in Dailies, which feature bland, generic forms, give the impression that they have been taken (and shared) thousands of times before, as if they don’t belong to anyone in particular. A crumpled venetian blind in an unadorned window and a cake of soap balanced on the edge of a bathtub push photography to the limit of banality and are uncomfortably familiar because of their sheer ubiquity. “The perspective is that of a pedestrian, the angles are like looking at things (rather than a tableau on which one is looking), and the things themselves are ones without much biography, like a paper cup, a plate, a window,” Demand said in a recent interview. His photo of two cups stuck in a chain-link fence resembles hundreds of variations available online, with everything from pieces of tree bark to beer cans substituting for those two cups. It is impossible to tell whether such photos are naïve encounters with reality or responses to other pictures with the same subject. For Demand, it doesn’t really matter. A meme is a meme, and its reach is more important than its origin. “The subjectivity of picture production today contrasts starkly with the objectivity we expected from a photograph two decades ago,” Demand has said. “That shift is what I found worth looking into. The format can be like a short haiku rather than a novel.”

“Daily #15,” by Thomas Demand © The artist/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York City

A haiku combines disparate perceptions of the world to produce an instantaneous recognition of relation. The perceptions themselves may not be particularly original, but the effect they produce is. Photography is a game played with familiar things in the hope of creating unfamiliar ones. Demand’s analogy suggests that preexisting images, rather than being a constraint, can open up different points of view; they can even act as a guide to making pictures not yet seen. For many young photographers, the idea that all photographs have already been taken doesn’t mean they can’t be taken again, differently, so that they are not so easily and quickly consumed.

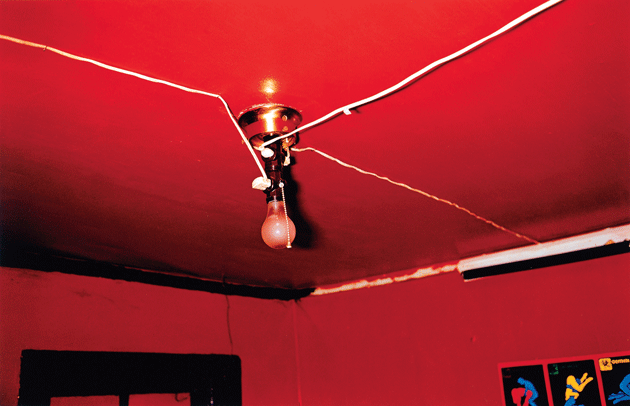

“Untitled (Greenwood, Mississippi),” by William Eggleston, whose work is on view at the National Portrait Gallery, in London © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York City.

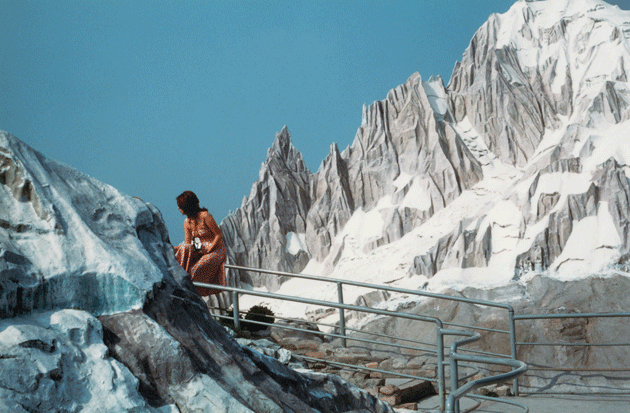

From Korea to Spain, there are so many young artists taking this approach, whose pictures flirt so casually with the commonplace, that it is not easy to recognize distinctive viewpoints. Museums and critics have largely ignored the work, most of which has never left digital space. Photographers such as Corey Olsen, Sam Clarke, Molly Matalon, Caroline Tompkins, and Winslow Laroche, to name a few, bring to their work a diaristic attentiveness that is as concerned with interpreting ordinary reality, moment to moment, as it is with sharing an experience or constructing a social identity. Their work is inspired by that of earlier artists who sought to rescue photography from clichés. In the 1970s, William Eggleston and Stephen Shore adopted neutral styles and focused their cameras on the quotidian, partly in response to the formality and sententiousness of black-and-white art photography. Their images of low-rent motel rooms, street corners, and diner breakfasts were criticized for elevating trivial subjects and for showing the world in color, which was associated with advertising. Artists around the world took note of their style, among them Luigi Ghirri (1943–92), whose quirky images flirt with Italian nostalgia only to reveal the country as a hall of mirrors, as artificial as a story by Italo Calvino.

One lesson the new generation appears to have learned from these antecedents is not to fight against clichés but to act as if they didn’t exist. As Ghirri said, “The effort we are inclined to make, daily, is one of rediscovering a gaze that negates and forgets what we know.”

“Rimini,” by Luigi Ghirri, from the series In Scala. Ghirri’s work was on view in April at Matthew Marks Gallery, in New York City © Estate of Luigi Ghirri. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York City

For a project entitled City Island, Corey Olsen created a book-length photo essay based on several visits he made as a student to a single neighborhood in the Bronx. City Island, which sits in the Long Island Sound near the Throgs Neck Bridge, is a place of seafood restaurants, waterside homes, and quiet streets that recall the Fifties. Olsen never aspired to discover an unknown City Island, but rather to treat it as he found it — as a tourist, as Demand’s pedestrian, who has stumbled upon a place he can’t quite believe exists. There are pictures of light-dappled houses, lobster-themed signage, a friend smiling in the bright sunlight, glimpses of shining nautical hardware. Nature here feels distant, mediated through generic architecture and photographic formulas, but always present in the ambient light. His City Island project gives the viewer the sense not of being there but of seeing the neighborhood through someone else’s eyes, someone who has noticed things you might not think are important and has made them seem worthy of a picture. No individual image is as dramatic as Eggleston’s red ceiling with a bare lightbulb, but together the photographs are transformed from disposable descriptions into a whole that is luminous and lingering.

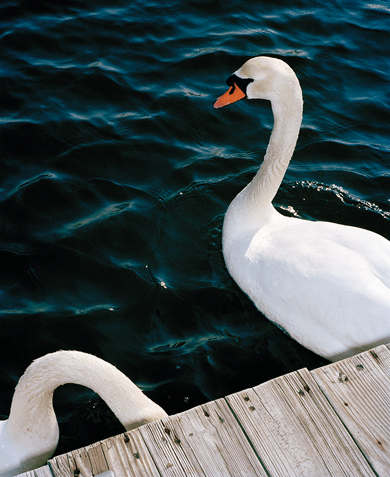

Such minor epiphanies spring from the consciousness of an increasingly transitory and unstable world, in which people move on, the planet warms, violence flares, and future prospects narrow. In the face of that uncertainty, objects stuck in fences, swans on blue water, and people squinting in the sun are a new generation’s haiku of temporary order, unlikely balance, momentary joy, laughable coincidence, and the sudden, piercing awareness of another person’s presence.