When I saw Ted Cruz speak, in early August, it was at Underwood’s Cafeteria in Brownwood. He was on a weeklong swing through rural central Texas, hitting small towns and military bases that ensured him friendly, if not always entirely enthusiastic, crowds. In Brownwood, some in the audience of two hundred were still nibbling on peach cobbler as Cruz began with an anecdote about his win in a charity basketball game against ABC’s late-night host Jimmy Kimmel. They rewarded him with smug chuckles when he pointed out that “Hollywood celebrities” would be hurting over the defeat “for the next fifty years.” His pitch for votes was still an off-the-rack Tea Party platform, complete with warnings about the menace of creeping progressivism, delivered at a slightly mechanical pace but with lots of punch. The woman next to me remarked, “This is the fire in the gut! Like he had the first time!” referring to Cruz’s successful long-shot run in the 2011 Texas Republican Senate primary. And it’s true—the speech was exactly like one Cruz would have delivered in 2011, right down to one specific detail: he never mentioned Donald Trump by name.

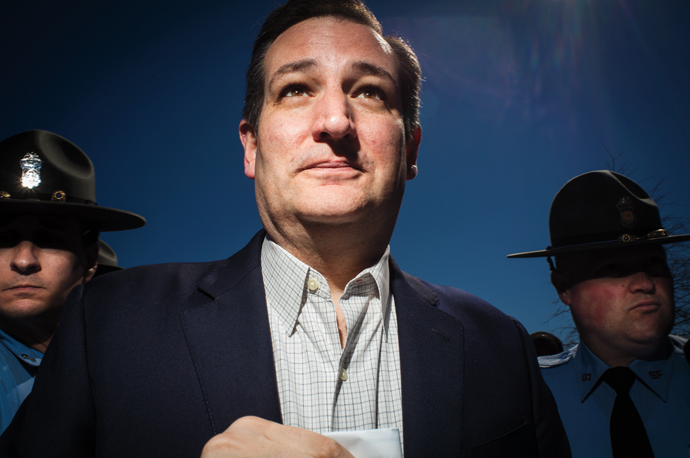

Photograph of Ted Cruz © Ben Helton

Cruz recited almost verbatim the same things Trump lists as the administration’s accomplishments: the new tax legislation, reduced African-American unemployment, repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, and Neil Gorsuch’s appointment to the Supreme Court. But, in a mirror image of those in the #Resistance who refuse to ennoble Trump with the title “president,” Cruz only called him that.

This may have been an accident or a coincidence, but Cruz is notorious for being both deliberate and evasive with his language. He was a competitive debater in college and law school—twice winning national titles—and, even in that environment, he was known for his ability to not answer the question at hand. “Ted was not about responding to anything,” as his debate partner told the New York Times. In Brownwood, he responded to (if he didn’t exactly answer) every question at length and peppered his neatly organized thoughts with references to the Constitution, John Stuart Mill, and, at one point, Les Mis.

The sound bite and the canned answer are the building blocks of all political rhetoric, but Cruz’s experience on the debate circuit and in the courtroom (as Texas’s solicitor general, he argued eight cases in front of the Supreme Court) has polished his style to a point of diminishing returns. Most politicians rehearse their prepared answers in hopes of giving them the illusion of spontaneity. Cruz appears to have accomplished the opposite: even his off-the-cuff remarks sound as though he’s memorized them. He is one of the few people—outside lower-tier Bond villains—who use the word “indeed” in regular conversation, and without irony.

Cruz’s meticulous, occasionally condescending demeanor can be off-putting. He rubs even fellow Republicans the wrong way. When Cruz’s Senate race started to narrow, the White House budget director, Mick Mulvaney, told a closed-door meeting of donors that they had cause for concern. According to audio obtained by the New York Times, he reminded them, “How likable is a candidate? That still counts.”

Cruz and his Democratic challenger, Beto O’Rourke, were dramatic opposites on any number of fronts: politically, certainly, but aesthetically too. And they were opposites in another way that political journalists aren’t supposed to acknowledge outright. O’Rourke had lived in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn before it gentrified. He was in a band and had a job moving art-gallery inventory. He retains a certain slinky grace, even though his hair is salt-and-pepper now and his day job is in Congress. He is, not to put too fine a point on it, kind of hot.

All of this is to say: O’Rourke is cool. He is effortlessly at ease in the way of high school prom kings. He has casual but undeniable charisma. A video of an answer he gave at a town hall lauding the right to kneel during the national anthem (“I can think of nothing more American”) was viewed more than 38 million times on Facebook. Ellen DeGeneres extended him an invitation to come on her show to talk about it, while LeBron James simply tweeted: “A Must Watch!!!”—emojis for prayer, strength, 100 percent, exclamation points—“Salute @BetoORourke for the candid thoughtful words.”

O’Rourke’s charisma has led to breathlessness in the profiles that were written about him, and there were a lot of profiles written about him: in GQ, Esquire,The Ringer, Time, the Washington Post, the New York Times, BuzzFeed, and Vanity Fair, where the word “Kennedyesque” first appeared and attached itself to him like a hill-country cocklebur.

All this was before the viral video of O’Rourke skateboarding in a Whataburger parking lot.

But the campaign would not have taken off had it been only journalists who swooned. O’Rourke, like Barack Obama, was the kind of candidate who inspires fan art, unofficial merchandise, and independent grassroots groups.

Cruz is not cool. He is aggressively, almost proudly, uncool. Although O’Rourke is just two years younger than Cruz, Cruz seems more than just older—he seems like he’s from a different product line. He is physically awkward and talks a little loud, he does not dress well, and he has a strange, high-pitched laugh. (For most of my life, that has been me.) He frequently quotes from Star Wars and Star Trek, and he enjoys reciting lines from The Simpsons in the characters’ voices. He has finely developed opinions on Robert Heinlein and Piers Anthony that he is eager to share. In Cruz’s autobiography-cum-campaign text, he writes about spending his high school weekends traveling around to Kiwanis and Rotary clubs, performing a memorized version of the Constitution (and ending with a “patriotic poem . . . set to rousing music”).

All these things resonate deeply for me, right down to an adolescent fascination with the Constitution, and so I’ve always had a soft spot for Cruz. I have been lonely in this affection—especially among liberals—which has puzzled me. Aren’t progressives supposed to be on the side of overly competent nerds? If you bristled at pundits opining on Hillary Clinton’s “likability problem,” shouldn’t the Republicans fretting about Cruz’s likability bother you as well?

Just before his presidential campaign ended, I wrote an essay about the connection I felt with Cruz, based on a shared love of science fiction and an even firmer connection to a shared familiarity with adolescent social rejection—and trying to do something about it. In his memoir, Cruz describes deciding “I’d had enough of being the unpopular nerd.” In middle school, he made a plan: “Okay, well, what is it that the popular kids do? I will consciously emulate that.” Cruz eventually discerned that he should brag less about his grades and at least try to play sports. I dreamed up a similar plan in ninth grade.

The big difference between us, I wrote back in 2016, was that Cruz declared that his plan “worked”—he was elected class president in high school. And I never went through with my plan, because I suspected that doing so would mean losing the very thing I wanted. Getting people to like me by acting like someone else might have made me popular, but I’d never feel accepted. I’d never feel known.

But maybe being known isn’t what Cruz was after.

Photograph of Ted Cruz merchandise © M. Scott Brauer

In the end, Trump didn’t go unnamed in Brownwood for very long. Cruz’s second questioner asked him directly, “Can you give us your opinion of the president’s job performance to this point?”

Cruz chuckled and began an answer that he’s given before: “President Trump says a whole lot of things I would never say”—there is some laughter—“but on substance, I’m actually quite happy with what’s getting done.” He added that his rule of thumb is that he won’t comment on “the tweet of the day” or “whatever it is that has the talking heads on cable news lighting their hair on fire.” This was a typically clumsy and unoriginal spin for Cruz; you can hear the same kind of thing from a dozen different Republican senators any night of the week on cable news shows. A woman in the audience called him on it, asking in a twang that underscored her suspicion, “What are some of the things you disagree with Trump about?”

Cruz started again with the canned answer, “As I said, he says all sorts of things I wouldn’t say . . .?” A male voice in the back interrupted: “You’re not brave enough!”

If Cruz heard him, he didn’t show it—and even if he did hear the jab, he couldn’t afford to respond: he needed that man’s vote.

But he shouldn’t have needed it. Historically, a Republican senator running for reelection in the ruby-red state of Texas could—oh, let’s say, shoot someone in the middle of Fifth Avenue and still win. (Considering how Texans traditionally view New York, that might actually sway some undecideds.)

For twenty years, statewide races in Texas were so reliably Republican that Democrats have had trouble fielding candidates willing to suffer the humiliation that comes with anemic public recognition and double-digit losses. Texas has had Republican governors since 1995. The state’s Senate seats have been in Republican hands since 1993, and its Electoral College votes haven’t gone to a Democrat since 1976. Cruz’s last general-election opponent, Paul Sadler, raised only 5 percent against Cruz’s $14 million—which at least makes his 16-point loss seem relatively economical.

The 2018 race wound up being more expensive for both parties, because O’Rourke outraised Cruz. Over the summer, a political scientist at the University of Texas told a reporter, “If you would have told me a year ago O’Rourke would have ten million dollars in the bank, I would have called you crazy.” And that was $10 million ago.

But even that kind of money shouldn’t be the deciding factor in Texas. In 2013, state senator Wendy Davis rose to fame during an ultimately doomed filibuster to stop further state infringement on women’s reproductive rights. Out of that ardor, she ran for governor and raised $36 million—and still lost by more than 20 points to Greg Abbott, who ran what amounted to a Rose Garden campaign from his perch as attorney general.

Cruz may have imagined a similarly distinguished and leisurely reelection—his first ad of the campaign was a dig at O’Rourke for changing his name from Robert to Beto as part of a more generally anti-O’Rourke jingle. But by the time I saw Cruz in Brownwood, the campaign was starting to slide from a high-minded path into something much grittier. The Texas GOP tweeted a mocking caption on an old photo of O’Rourke, dating from his days as a musician, wearing a dress. (His real sin was ripping off Kurt Cobain.) Conservative-friendly outlets tried to drum up interest in a twenty-year-old DUI charge that O’Rourke has never tried to hide.

Whatever lofty ideas Cruz may have had before O’Rourke’s popularity grew, in its aftermath he reverted to the strategy that won Trump the 2016 presidential election: forget about swing voters, embrace the base. Which, in 2018, means embracing Trump himself, sometimes literally.

Donald Trump did plan to come to Texas to headline a rally with Cruz. Immediately after the rally was announced, an activist group bought a mobile billboard near the venue to display some of the nastiest tweets Trump directed at Cruz during their 2016 contest for the GOP nomination. Among the tweets at their disposal: “Why would the people of Texas support Ted Cruz when he has accomplished absolutely nothing for them! He is another all talk, no action pol!” And: “How can Ted Cruz be an Evangelical Christian when he lies so much and is so dishonest?”

Here are some of the things Cruz’s fellow lawmakers said about him during his freshman term as senator: Republican Representative Peter King judged, “Cruz isn’t a good guy, and he’d be impossible as president. People don’t trust him.” King further promised, “I’ll take cyanide if he ever got the nomination.” Senator Marco Rubio—campaigning against him at the time—said, “Ted has had a tough week because what’s happening now is people are learning more about him.” Former House Speaker John Boehner called him “Lucifer in the flesh.” Senator John McCain dubbed him a “wacko bird.” In 2016, Senator Orrin Hatch warned, “I think we’ll lose if he’s our nominee.” Regarding the choice between Cruz and Donald Trump, Senator Lindsey Graham lamented, “It’s a lot like being shot or poisoned: I think you get the same result.”

And that’s just the Republicans. Democrats such as Al Franken were relatively charitable: “You have to understand that I like Ted Cruz probably more than my colleagues like Ted Cruz. And I hate Ted Cruz.”

Cruz knows all about these insults; he invited them. He came to the Senate in 2013 as part of a wave of Tea Party–supported candidates whose campaign-trail denunciations of fellow party members were not easily forgotten by Establishment types, but Cruz stood out even among those zealots for his willingness to abandon Washington and Senate norms.

He went out of his way to earn the ire of lawmakers because he wasn’t trying to be popular with them. He had his eyes cast on a wider audience and a more ambitious goal. When he ran for president in 2016, part of his stump speech included a proud reference to the New York Times, which, in his telling, “opined, ‘Cruz cannot win, because the Washington elites despise him.’?” (This is a paraphrase, of course.) He would then pause (for a disconcertingly consistent amount of time) and hit the kicker: “I kind of thought that was the whole point of the campaign!”

It was the whole point of the campaign, explicitly so. Cruz’s presidential run was carefully crafted to appeal to what some pollsters called “the missing white voters.” His campaign figured them to be non-college-educated white people; as the columnist George Will put it, paraphrasing a campaign strategist, these nonvoters were “disappointed by economic stagnation and discouraging cultural trends for which Republican nominees seemed to have no answers.” Cruz’s reputation as “the most hated man in Washington” was their selling point, and if Washington elites yelped about Cruz stepping on their toes, it was just a chorus that confirmed his willingness to fight for conservative principles. If liberals also complained about Cruz’s reddest-meat social positions—less gay marriage, more guns!—all the better. According to Cruz’s strategist, this approach would not only sufficiently motivate conservative nonvoters to give their candidate the delegates needed for the GOP nomination but also be enough to garner the 270 Electoral College votes needed to make it to the White House.

Of course, Cruz and his team were exactly right about the success of this strategy. He just wasn’t the candidate elected by it.

When Cruz returned to the Senate, the ill will remained. He did, however, start a Senate pickup basketball game. Perhaps he also stopped bragging about his grades.

At the end of the campaign stop in Brownwood, a reporter recited all of Cruz’s barbs against Trump and then asked about what was then only a possibility: He had said all those things, she noted, “yet you’ve invited him to come and join you on the campaign trail in Texas. Can you talk a little bit about what motivated you and why you changed your mind about him?”

Cruz seemed delighted to deliver a correction: “To be honest, actually, those stories and those headlines were not accurate. I was asked if I thought Trump would come to Texas and said, Sure, it’s likely that he would, and of course I would welcome him. He’s the president of the United States—of course we would welcome him in Texas.”

After speaking to the gathered press, one of Cruz’s staff told me to stick around, that the senator would give me some time after he finished another one-on-one interview.

“Well, you’ve come a long way,” Cruz told me. It was a nice thing to say, but there wasn’t a great reason for him to talk to me. I had told his staff that this piece would come out pretty much as the campaign ended—as if there were many Cruz votes to be found among my audience to begin with. But I also knew that there had been people on his staff who had read my essay about my soft spot for the senator. If nothing else, maybe Cruz wanted to talk about the latest Star Trek reboot.

We wound up speaking off the record, at his request, for more than an hour. Very little of what he said would be considered controversial or reveal an attitude or position that he hasn’t already avowed publicly. The only things that could have possibly risked a single vote were a few poignant spikes of genuinely endearing self-deprecation. All of which I later badgered his staff to let me use, to no avail.

Admittedly, the kind of stories I find charming might not scan the same way for the voters Cruz was trying to reach. The Cruz campaign later released an ad blasting O’Rourke for dropping f-bombs on the trail. (“If Beto shows up in your town, maybe keep the kids at home,” the ad warned.) And the patrons at Underwood’s were there for “fire,” not nuance. If Cruz was hoping to ride Trump’s coattails, what role could self-awareness or vulnerability possibly play? Both are kryptonite to their Superman.

As is true for so many of us, the past two years of Cruz’s life have been defined by Donald Trump, and Cruz has had a more intensely personal relationship with Trump than most. In 2016, they were the last two men standing in the final, bitter weeks of the Republican primary. They viciously attacked each other, Trump with his usual brief but catchy invective (“Lyin’ Ted”) and Cruz more operatically (a “pathological liar,” a “serial philanderer,” and “utterly amoral”).

But Trump burst past the boundaries of even marginally acceptable discourse by also attacking Cruz’s wife and father. He retweeted an unflattering comparison of Heidi Cruz and Melania Trump; he accused Cruz’s Cuban-born father of being part of the Kennedy assassination. At the end of the summer, Cruz retaliated by refusing to explicitly endorse Trump’s nomination at the GOP convention, instead urging delegates to “vote your conscience.” He was met with an arena’s worth of howling boos.

But rather than emerge as part of the Never Trump coalition, Cruz announced his support for Trump just two months later. He said his decision came after “prayer and searching my own conscience,” a statement that telegraphed reluctance. There was no talk of American greatness or any real excitement, just a solemn observation: “A year ago, I pledged to endorse the Republican nominee, and I am honoring that commitment. And if you don’t want to see a Hillary Clinton presidency, I encourage you to vote for him.”

It was almost as though Cruz wanted credit for the naked transactionality of the endorsement, the political equivalent of crossing his fingers behind his back. He pointedly refused to directly answer the question about whether or not he’d changed his mind about Trump, and instead just insisted that Republicans were faced with “a binary choice.” Between Trump and Hillary Clinton, he said, he was “Never Hillary.”

The radio host Glenn Beck, who had spent $500,000 of his own money campaigning for Cruz, pressed Cruz about his decision. “Have you spent an enormous amount of time with Donald Trump?” Beck asked. “Do you have new information that has made you say: ‘Oh, my gosh, he’s now not a sociopathic liar. He is not the guy I very eloquently spelled out for over a year, and now suddenly there’s a reason to believe him’?”

Since then, Cruz’s public statements about the president have been given with somewhat more enthusiasm but are just as careful. He focuses exclusively on policy and flatters Trump’s base. He harps on the parts of Trump’s agenda that align with his. In two years, however, he has avoided saying anything that would directly contradict what he once said about the president’s character. Whether or not you think this is a meaningful distinction probably depends on whether or not you are Ted Cruz.

Even people who don’t follow politics know Cruz as a punch line. A caricature of him as a toxic, ruthless figure has been memorialized in memes and Onion headlines: “Scientists Warn All Plant Life Dying Within 30-Yard Radius Of Ted Cruz Campaign Signs,” “Ted Cruz Asks Central Park Hansom Cab Driver How Much It Costs To Whip Horse For An Hour.”

After the very first GOP presidential debate, a neurologist’s first-person musings in a column in the web version of Psychology Today on “what unsettles me so when I watch the freshman senator” went viral. The problem was a literal version of what people often say about psychopaths: Cruz’s smile doesn’t touch his eyes. Not only do his crow’s-feet not crinkle sufficiently when he smiles, but, the doctor wrote, “the outside of his eyebrows bend down, too, when he emotes, something so atypical that it disturbs me.” A blog that aggregated this assessment was more direct about the effect: “Science Has Figured Out Why Ted Cruz Has A Punchable Face.” (More Onion headlines: “Ted Cruz Provides Detailed Response To Moderator’s Question About Why His Face So Fucking Infuriating,” “Brutal Anti-Cruz Attack Ad Just 30 Seconds Of Candidate’s Photo Displayed Without Any Text, Voiceover, Music.”)

The year 2016 also sustained a cottage industry based on the satirical proposition that Cruz was the Zodiac Killer. What started out as a joke on Twitter birthed explainer pieces in legitimate news organizations and one commissioned poll, which found that 10 percent of Floridians did think Cruz was the Zodiac Killer and 28 percent were “not sure.” One organization raised an estimated $69,000 for abortion access in Texas by selling ted cruz was the zodiac killer T-shirts.

Two years later, Cruz is still on the short list of politicians whose names regularly figure in pop-culture gags. The Onion, again, last spring: “Nation Feels First, Only Pang Of Sympathy For Zuckerberg After Watching Him Engage With Ted Cruz.” Stephen Colbert, after the Texas primary showed an unusually large turnout for Democrats but before everyone swooned for O’Rourke, joked, “No candidate gets voters more excited than ‘not Ted Cruz.’?” (As O’Rourke’s candidacy took off, the Onion weighed in again: “New Ted Cruz Campaign Ad Features His Kids Begging For Beto O’Rourke To Be Their New Dad.”)

I came home from Texas to an apologetic text from one of Cruz’s communications people. Cruz wanted to give me some quotes on the record. Could I possibly come to Washington for an interview there? Of course I could.

In the week before I went to D.C., the tone of the race continued to decline, and Cruz leaned even more heavily into positions that echoed Trump. When O’Rourke’s town-hall response on the national anthem went viral, Cruz responded on Twitter with a grasping reference to “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon”—using Bacon’s own approving retweet of the video as a link in the pop-culture connecting game. The campaign also produced a video featuring a double-amputee Vietnam veteran, to whom Cruz made the solemn, painfully literal promise—with a helpful hashtag: “#IStand for the veterans like Tim Lee . . . Tweet #IStand if you’re proud to Stand, too!”

I wondered whether he really meant it. I could hear the echo of Cruz’s youthful program: “Okay, well, what is it that the popular kids do? I will consciously emulate that.” I’d heard him defend the internet kook Alex Jones’s right to speak, even though Jones had amplified the same Kennedy-assassination theory that Trump referred to during the campaign. I wondered whether his elaborate attacks on the NFL protests hid another example of Cruz trying to cross his fingers behind his back.

When we finally sat down in Washington and I asked him to square his support for Jones with his criticisms of the NFL players, his response took up twenty minutes and ranged over the Citizens United case, the Supreme Court’s 1977 ruling that Nazis could march in Skokie, Illinois, and the congressional testimonies of Google and Facebook. He talked about monopolies and public forums and the Sierra Club and how “every single person” on a military base “stops what they’re doing, immediately what they’re doing” to stand at attention when the national anthem is played.

I don’t know why I expected a straight answer; his two positions aren’t easily squared. But because I am attuned to Cruz’s precision with words when he’s talking about anything related to Trump, I became convinced that there was some space for nuance in the way Cruz talked about the NFL protests, that he didn’t actually, totally, completely agree with what Trump said about the protesters. Trump regularly called for the players to be punished for kneeling. But was Cruz calling for that? I couldn’t find it in his statements. He denounced the protests, yes. He borrowed the talking point that alleged these “multimillionaire elite athletes” of “great privilege” were somehow hypocrites for saying America still harbored injustices. He joked that the NFL shouldn’t risk alienating half its audience, which suggested that perhaps the free market could provide whatever consequences were warranted. But he didn’t say the players should be dragged off the field. He didn’t say they should be kicked out of the country. Was there daylight between him and Trump?

I began to pester his communications people about it, and I bored my friends with what I considered a bona fide scoop: Ted Cruz might harbor beliefs that are somewhat less reprehensible than the statements of the president!

It became clear that, whatever I thought Cruz’s slightly less reprehensible views might be, he was not interested in appearing to be anything other than fully aligned with the president. Denouncing the NFL players’ anti-police-brutality protests became a regular part of Cruz’s stump speech. The campaign put out an ad that made it seem, in his own comments, as though O’Rourke had commended flag burning.

I was surprised and disappointed by this turn of events, but not for any good reason. I believe that the policies Cruz supports are abuses of the power he has. On social and economic issues alike, his positions tend to favor those who are already doing fine at the expense of the vulnerable. I am exactly the sort of bleeding-heart liberal whose beliefs in social safety nets and “equality of outcomes” Cruz has spent his career attacking in speeches and beating back politically. In every interaction we had, Cruz was insisting that I take him exactly at his word.

Cruz and I went around and around about his lingering negative public perception, which clearly frustrates him. (This is in contrast to, say, Dick Cheney or Karl Rove, who often seemed somewhat bemused, if not actively delighted.) Twice he asked me, “Isn’t it possible I just believe this stuff?”

At this point I feel I know Cruz well enough to say that I’m sure no evidence exists to prove otherwise. I wanted to find something in common between us to soothe my own half-healed playground wounds. Now I think that whatever childhood hurts Cruz may have nursed, there is nothing but scar tissue there now. He interprets people’s suspicions about his motives and his sincerity as a sign that they don’t believe what he says. But his real problem is that he says exactly what they want to hear. His lifetime of discipline and rehearsal—his commitment to his grand plan—is the only thing about him that telegraphs as true.

Cruz’s other theory for why he can’t shake his reputation for unpleasantness is that “people believe the caricature.” It’s hard to blame them, though. The caricature is what he’s given them to believe.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Greg Abbott had campaigned as lieutenant governor. We regret the error.