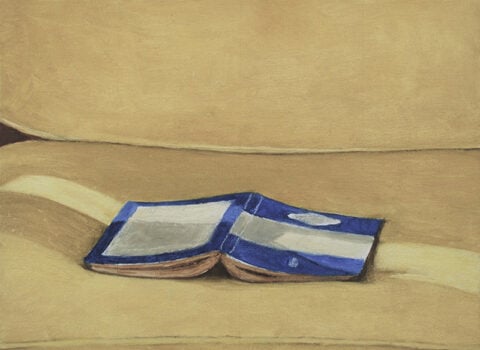

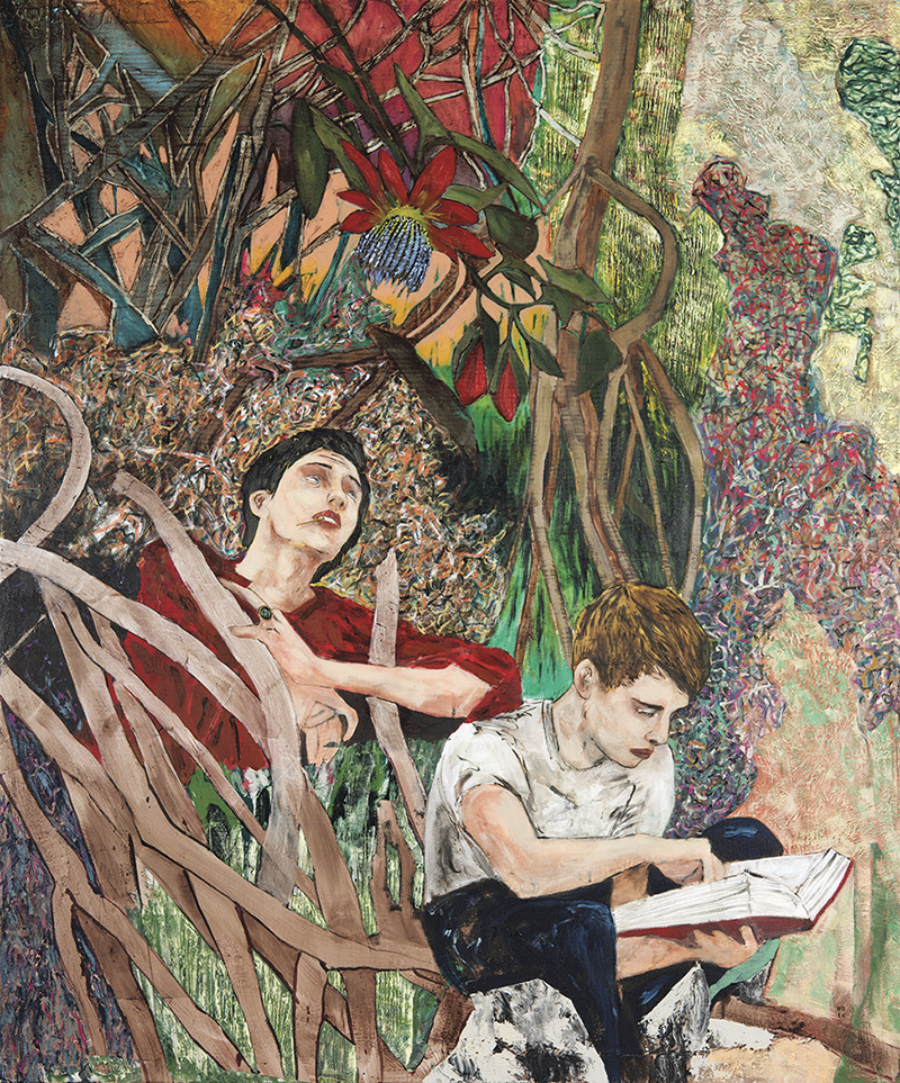

Reading from a blank book, by Hernan Bas. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York City

Discussed in this essay:

The Childhood of Jesus, by J. M. Coetzee. Penguin Books. 288 pages. $16.

The Schooldays of Jesus, by J. M. Coetzee. Penguin Books. 272 pages. $16.

The Death of Jesus, by J. M. Coetzee. Viking. 208 pages. $27.

The novels of J. M. Coetzee’s Jesus trilogy take place in a purer world than our own and, on the surface, a simpler one. In this world, which might be an afterlife or a waystation in the transmigration of souls, no one, except newborns, is native, and everyone speaks the same language, “beginner’s Spanish.” Arrivals in this land have been “washed clean” of their memories, given new names, and assigned ages by their looks. Ample state services—housing, education, medicine—and jobs are available to all. The climate seems to be temperate: sometimes it’s hot, sometimes it isn’t, and once in a while it rains. There are seals by the shore, and a mild infestation of rats in the warehouses that store the grain that arrives every day by ship. The diet is mostly vegetarian—crackers, spaghetti, bean paste; meat is hard to come by, as are spices. The world Coetzee has constructed bears resemblance to his prose style. “I do believe in spareness,” he once remarked. “Spare prose and a spare, thrifty world: it’s an unattractive part of my makeup that has exasperated people who have had to share their lives with me.” It’s hard not to conclude that he has imagined a world in the shape of his own mind.

What is missing from this world? Technology is stuck at the level of the 1950s, not coincidentally the era of Coetzee’s youth. There are newspapers, refrigerators, televisions, and automobiles but no computers. Medical science is a matter of injections and blood transfusions, not X-rays, CAT scans, and arthroscopes. Progress itself is scorned; workers on a dock reject a crane that would make their tasks more efficient. Politics goes unmentioned, despite the ubiquitous presence, mostly benevolent, of the state: there’s a census, a public school system, and a social safety net, but no mention of leaders, wars, or international rivalries. History is only present in echoes, such as a pet dog named Bolívar. There is talk of film and music and dance, but few recognizable artworks, among them Don Quixote, a song of Goethe’s, and a Mickey Mouse cartoon. We hear nothing of the major religions, but everyone seems to believe in reincarnation. No one has a sense of irony or sees “any doubleness in the world.” There are shops and even advertising circulars, but the effulgences of capitalism are absent, as are the trappings of bourgeois society. Hardly any differences in class can be detected in this land of migrants, and the only reference to race is mention of “Red Indians” in the Disney cartoon. There is no oppressor and no oppressed, no one victorious and no one defeated, no legacies of guilt or victimization. We are a long way from the South Africa where Coetzee was born in 1940, and the postapartheid South Africa he left in 2002 for Australia.

Into this welcoming but austere and culturally blank world come Simón and David, a man and a motherless boy who met on the ship that brought them from the life they no longer remember. The Childhood of Jesus (2013) traces their arrival in the city of Novilla. Simón assumes guardianship of the boy and searches for his mother. Following the advice of “the voice that speaks inside us,” Simón recruits a woman named Inés to fill the role after seeing her playing tennis with her brothers. Their adjustments to life in a new land are uneasy, and there’s something out of the ordinary, even supernatural, about the boy. At the least, he resists socialization. After municipal authorities try to put him in a remote reform school, Simón, Inés, and David escape Novilla by car. The Schooldays of Jesus (2016) follows the makeshift family’s assimilation to life in the inland city of Estrella. David enrolls in its dance academy, where he is recognized as a gifted child. A scandal ensues when the school’s janitor, Dmitri, murders David’s beautiful dance instructor, Señora Arroyo; he is tried, confesses, and is sentenced to confinement in a psychiatric ward. In The Death of Jesus, David abandons Simón and Inés to live in an orphanage. He then falls mysteriously ill, becomes an object of notoriety from his hospital bed, and speaks gnomically of delivering his “message” to the world before he leaves it. At last, he dies.

If the setting of these novels is minimalist and ahistorical, and their action the stuff of melodrama and pulp, their texture is philosophical conversation. In one of the trilogy’s many allusive jokes, David refers to Mickey Mouse’s dog Pluto as “Plato.” The residents of Novilla tend to speak as if they’ve been plucked from one of Plato’s dialogues, debating such basic questions as the nature of love, the purpose of work, and the chairness of chairs. Simón finds this exasperating at times, but more and more he engages, and the conversations ease his adjustment to a land where both passion and irony are mostly absent. In Childhood, the largest question is whether the characters are living in the best of all possible worlds or the only world, whatever “shadows of memories” linger in Simón’s mind. The problems of justice and redemption follow from the murder at the center of Schooldays. Mortality looms over the final volume. The conflict between passion and rationality, the disparity between appearance and reality, and the nature of numbers and words are turned over throughout the trilogy. None of these issues becomes any simpler as David asserts himself as a kind of half-pint oracle: a boy who resists systems of thought like arithmetic, teaches himself to read, and writes on the classroom blackboard, “I am the truth.”

The novels’ titles are at once literal (in that they name the stages of one character’s life) and a puzzle (in that they invite the reader to identify the character with someone whose famous story is altogether different). Is David a redemptive figure? A savant? In 2012, in Cape Town, before reading from the first novel, as yet unpublished, Coetzee told the audience: “I had hoped that the book would appear with a blank cover and a blank title page, so that only after the last page had been read would the reader meet the title, namely The Childhood of Jesus. But in the publishing industry as it is at present, that is not allowed.” Such an unconventional placement of the title would no doubt alter the experience of readers disciplined enough not to peek. In a book with plenty of allusions to Christian scripture but no characters who practice the religion, David would come across less like a possibly divine savior than a bright but obnoxious and delusional child, and Simón, who has a vision of David in a loincloth riding aloft in a chariot pulled by two white horses, would himself be a candidate for psychiatric counseling. The title on the last page would come as a retroactive shock.

The David of The Death of Jesus is different from the boy we encounter in the first two novels. He is ten years old (four years older than in Schooldays), tall, and athletic, a star on the soccer field and the leader of the boys in his neighborhood and at his school. There he has a special, quasi-teacher status, showing up on his own schedule to perform dances of his own invention. His attitudes about numbers—a kind of nominalism according to which each has its own special qualities beyond the rules of arithmetic—have hardened into casual dogma, such that he disdains a watch Simón and Inés have given him for his birthday because its face arranges the digits in an ordered circle against their true natures. The makeshift family’s life has been stable until the arrival at a pickup game of Dr. Julio Fabricante, head of a local orphanage of two hundred children. He tempts David away from his adoptive parents with the promise of playing for an organized team. Beyond their wish to keep him, Simón and Inés fear that the boy will be corrupted: one night he comes home in muddied clothes after hanging out with teenage orphans, having broken and abandoned his bicycle, and smelling of cigarettes. As a pretext for moving into the orphanage, David claims that, besides not being his “real parents,” Simón and Inés have mistreated him, an accusation that hurts Simón profoundly and that the boy admits to fabricating: “Things don’t have to be true to be true,” David says. He and Simón argue similarly about the story of Don Quixote. Notably, David knows that story—which he understands as “veritable history” rather than fiction—not from Cervantes but from an illustrated children’s edition adapted by “a man named Benengeli.” He is not privy to the authentic version of the novel, just as Coetzee’s readers don’t know what his characters sound like in beginner’s Spanish.

Each of the novels rehearses David’s separation from, and possible betrayal of, Simón. Inés is the first to take David away, in Childhood, until she and Simón come to an uneasy and chaste way of being together after he fixes her toilet (leading to his contemplation of the “pooness of poo” and the realization that the boy he thinks might be divine also defecates). After getting lost on the street, David spends time in the company of a reprobate Simón knows from the docks named Señor Daga, who shows him cartoons on television and a novelty pen with a lady inside it whose clothes fall off when you turn it upside down. He also gives David a jar of magnesium powder that causes a small explosion and temporarily blinds the boy when he dips a candle in it (“Am I inside the mirror?” he asks in his oracular way). At last the authorities send him to reform school, but he escapes, and the family flees Novilla. There, the teachers of the dance academy seem suspicious to Simón and Inés, especially after David petitions to move into the school as a boarder. Simón goes looking for him one weekend and finds him at a nude beach with his teachers. Simón comes to view the school as a benevolent cult and the best place for David to study, even after the murder committed by the Daga-like caretaker Dmitri, who had shown David dirty pictures that, along with the sight of his victim’s body, had given the boy nightmares. When the census threatens to expose his flight from reform school, Simón hides him in a cupboard. Throughout, Simón’s yearning for paternal affection is as persistent and strong as his protective feelings toward the boy. David’s affinity for sleazy men like Daga and Dmitri is the inverse of Simón’s drift away from mostly unquenched sexual desire and passion toward a way of living governed by reason, moderation, and self-denial.

David has a softening effect on these men, as he has on Inés, who seems a coldhearted snob when we first meet her on the tennis court. David’s illness, its symptoms, and its various misdiagnoses, including one called Saporta syndrome, are a MacGuffin designed to deliver him to a death beyond simple explanation; he describes his condition only as “falling.” Dmitri returns to the story as an orderly in the hospital where he is supposed to be confined to the psychiatric ward. (“I am cured,” he explains.) He calls David his “master” and sits at his bed awaiting the delivery of his “message.” From his bed, the boy tells stories to Dmitri and other young visitors, among them children from the dance academy and the orphanage, about Don Quixote. These stories are Quixote fan fiction with a biblical flair, but they tend to take wrong turns or simply trail off. In one, confronted by a “virgin” with a baby and two men she has slept with (Simón thinks but doesn’t say that David doesn’t know the meaning of the word “virgin”), Quixote places the infant in a tub full of water and demands that the father step forward. When neither man does, he lets the baby die. David tells this story the day after demanding he be allowed to have his pet dog Bolívar and a lamb called Jeremiah that belongs to the dance academy spend the night in his room. By morning, Bolívar has mauled Jeremiah.

David the boy was indulged and obnoxious; David the dying preteen is a moody and confused crank, but his charisma is undeniable. After his death, the orphans of Fabricante’s institution go on a looting spree. Alyosha, a serene employee of the dance academy, explains the events to Simón:

Bands of them have been racing from shop to shop, overturning displays, haranguing shopkeepers for charging too much. The just price! That is their cry. In one of the pet shops they broke open the cages and set the animals loose—dogs, cats, rabbits, snakes, tortoises. Set the birds loose too. Left only the goldfish. The police had to be called in. All in the cause of the just price, all in the name of David. Some of them claim they have had mystic visions, visions in which David appeared to them and told them his bidding. He has left a huge mark behind. None of which surprises me. You know how David was.

It’s clear that David’s appeal lies in his disregard for mathematics and his attitude toward animals, which he sees as close to human. (Earlier in the novel, he disavows meat and expresses a desire not to eat fruit or vegetables because they are living.) So if David is a prophet of sorts, his message lies in protest against the rational order of things and a hierarchy of nature with human beings at the top. Even in Novilla and Estrella, where everyone seems to be a new arrival, these systems are cast as novel developments. Near the end of Schooldays, we get a glimpse of the only bit of mythology in the trilogy that is unique to their world. Señor Moreno, a guest lecturer at the dance academy, gives a talk on “Metros the measurer”:

“A shadowy figure, Metros,” Moreno is saying. “And like his comrade Prometheus, bringer of fire, perhaps only a figure of legend. Nevertheless, the arrival of Metros marks a turning point in human history: the moment when we collectively gave up the old way of apprehending the world, the unthinking, animal way, when we abandoned as futile the quest to know things in themselves, and began instead to see the world through its metra. By concentrating our gaze upon fluctuations in the metra we enabled ourselves to discover new laws, laws that even the heavenly bodies have to obey.

“Similarly on earth, where in the spirit of the new metric science we measured mankind and, finding that all men are equal, concluded that men should fall equally under the law. No more slaves, no more kings, no more exceptions.

“Was Metros the measurer a bad man? Were he and his heirs guilty of abolishing reality and putting a simulacrum in its place, as some critics claim? Would we be better off if Metros had never been born? As we look around us at this splendid Institute, designed by architects and built by engineers schooled in the metra of statics and dynamics, that position seems hard to maintain.”

Of course, “that position” is the one espoused by David, who rejects mathematics and the hierarchy of living things, and in a milder sense by his music teacher, Juan Sebastián Arroyo, who says that just because everything can be measured doesn’t mean it should be. David rejects the tyranny of rationality and the idea that there are no exceptions: to him everything has a singular essential nature. The mystery of his death—the rioting orphans blame it on a conspiracy of doctors—shows the limits of scientific explanations. David acquires an immediate posthumous mystique among the orphans, Dmitri, and his classmates at the dance academy, who put on a memorial show dramatizing episodes from his life in a comic manner (including the one of the dog eating the lamb, which can also be seen as a replay of Dmitri’s murder of Señora Arroyo). But it may be Simón who is the proper recipient of David’s message. Dmitri says as much to him in a letter at the end of the novel:

The fact is, authentic sinners like old Dmitri were too easy for him. It was types like you that he wanted to save, types who presented him with more of a challenge. Here is old Simón, with his more or less unblemished record, a good fellow though not excessively good, with no great hankering after another life—let’s see what we can do with him.

“Another life”—the phrase recurs in these novels over and over. There are a few dissenters, among them stevedores in Novilla who debate the idea idly. In Death, Simón asks one of David’s nurses, “Do you not believe in a life to come?”

I do. I do. But the life to come will be here on earth, not among the dead stars. We will die, all of us, and disintegrate, and become material for a new generation to rise up from. There will be a life after this one, but I, the one I call I, will not be here to live it. Nor will you. Nor will David. Now please let me go.

The concept of another life allows Simón to understand his own life and its limits, allowing for the possibility that things have been different before and might be again. The lesson of David’s life and death are about the limits of understanding. After the boy dies, Bolívar goes missing and Simón considers adopting a dog called Pablo that is taken by other owners. He ponders a dog’s notion of death:

Dogs do not understand death, do not understand how a being can cease to be. But perhaps the reason (the deeperreason) why they do not understand death is that they do not understand understanding. I Bolívar breathe my last in a gutter in the rain-lashed city and at the same moment I Pablo find myself in a wire cage in a stranger’s backyard. What is there that demands to be understood in that?

Yet understanding death and why he is where he is have been Simón’s questions throughout the novels. In this he is little different from animals, he realizes. In the final scene of the trilogy he pages through David’s Don Quixote, a used copy discarded from a Novilla library, and finds notes from two previous borrowers answering a librarian’s question about the message of the book—one reads, “listen to Sancho because he is not the crazy one,” and the other, “Don Quixote died so he could not marry Dulcania”—but nothing from David. “A pity,” Simón thinks. “Now it will never be known what, in David’s eyes, the message of the book was or what most of all he remembered from it.”

We could say something similar about the Jesus trilogy, and many critics have, calling the novels “utterly cryptic,” “unfathomable,” or “allegorical” but lacking in “a clear correlative” outside themselves. To say that the message of these novels is something about the limits of human understanding, or that they dramatize the conflict between two different ways of seeing and being in the world, broadly represented by passion and reason—and that the contest comes to a draw—may be unsatisfying, but only if you are expecting to find a pat message. What the reader will remember will be the pleasures available to anyone: the deadpan humor, the swoons of their melodramatic thriller plots, and the beguiling weirdness of the world Coetzee has constructed. These are not merely surface pleasures. The novels teach you how to read them without recourse to reading or rereading Plato, Wittgenstein, Cervantes, Dostoevsky, or the Gospels. The reader’s experience mirrors Simón’s comic education. The novels’ philosophy lives in an autonomous zone.

At the same time, a substantial academic literature has grown up around Coetzee’s life and career that demonstrates the trilogy’s layers of meaning. A defining aspect of Coetzee’s early life and his writings about it is the shame he felt as he came to understand the racial hierarchy of apartheid South Africa. The emotion pervades Boyhood (1997), the first volume of his autobiographical trilogy. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has argued that the absence of racial difference in Childhood of Jesus, despite Spanish as the lingua franca, represents Coetzee’s attempt to imagine “pre-colonial Africa.” There is a story that recurs in Boyhood and Childhood that lends this idea some credence: the story of the three brothers. In the tale, which John of Boyhood hears from his mother and David hears from Inés, there are two brothers who arrogantly ignore those in need while the third “helps the old woman to carry her heavy load or draws the thorn from the lion’s paw.” In Boyhood, John interprets the story in racial terms:

There are white people and Coloured people and Natives, of whom the Natives are the lowest and most derided. The parallel is inescapable: the Natives are the third brother.

In his book of memoir and criticism on Coetzee, In the Middle of Nowhere, Jonathan Crewe, a South African scholar of English who taught beside Coetzee at the University of Cape Town in the 1970s, writes:

The parable’s simple inversion of racial hierarchy may be taken as the boy’s first, benevolent step towards rejecting the dominant ideology of white racial purity and supremacy, but it hardly represents an escape from racial thinking. Perhaps there is no subjective escape, ever, in so heavily racialized a society as South Africa.

In Childhood, no such escape is necessary. David, an essentialist, wants to be the third brother himself. Simón explains to him that even if Inés had two more sons, David would always be the first brother. But because the boy rejects the idea of numeric order, he rejects the very concept of hierarchy. In the fictional world Coetzee has constructed for David, no escape is necessary. He need not be born third to be the third brother: it’s already his nature. He is immune to shame.

Crewe’s affectionate portrait of Coetzee includes several details that suggest autobiographical readings of the Jesus trilogy. He writes of “a genre of Coetzee anecdotes, in which John was the man to whom bad things happened.” In one such story, rabbits that he bought for his children as pets “turned feral and began to cannibalize each other”—perhaps the source of the dog mauling the lamb in David’s hospital room. In a broader sense, Crewe writes that Coetzee was part of a wave of professors who brought professionalization and knowledge of French theory to the South African academy. Having studied mathematics as an undergraduate and worked as a computer programmer for IBM in London during his twenties, Coetzee did his early work on Beckett in “stylometrics,” the use of computers to study literary texts, and wrote computer-generated poetry before turning to fiction. But he soon renounced these methods and by the end of his academic career it’s clear he believed the study of literature itself had been devalued in a process of “rationalism,” a situation he dramatized in earlier novels, among them Disgrace and Elizabeth Costello. He uses the word in his obituary for Nelson Mandela: “he was blindsided by the collapse of socialism worldwide; the party had no philosophical resistance to put up against a new, predatory economic rationalism.” He seems to mean neoliberalism, and in the Jesus trilogy it is the tyranny of Metros the measurer that David rebels against.

There are other elements of Coetzee’s life and work that appear in the Jesus trilogy. You could add the 2010 death of his brother David, dedicatee of Childhood, and the death by falling of Coetzee’s son Nicolas in 1989. They are fragments Coetzee has picked up and transformed within a painstakingly imagined world. In his 2016 study of the author’s archive at the University of Texas at Austin, J. M. Coetzee and the Life of Writing, David Attwell argues that “Coetzee’s writing is a huge existential enterprise, grounded in fictionalized autobiography. In this enterprise the texts marked as autobiography are continuous with those marked as fiction—only the degree of fictionalization varies.”

Coetzee, Attwell writes, begins his work “personally and circumstantially” and his drafts pass through many stages of “self-masking.” “Twelve, thirteen, fourteen versions of a work are not unusual.” The books that emerge are neither strictly realist nor traditionally allegorical. Plot is an unstable element throughout, and though Coetzee starts with a genre and perhaps a specific model in mind, the allusions in his work are usually late additions. Attwell calls the process “deliteralization.” He uses the term in reference to Life & Times of Michael K, another book in which race is both present and absent in a world that is like our own but is not, a South Africa of the near future torn apart by a violent revolution. It was Coetzee’s first masterpiece. His late trilogy (Coetzee is eighty this year), displaying marks of the same process pursued to more radical ends, is another.