Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (pt. I 1605, pt. II 1615)

The world of Phillip II sits at the heart of the Golden Century of Spain. Its empire spanned the globe. It was the envy of Europe. Its coffers bulged with silver and gold from the New World. Spanish armies brought repression to the Low Countries and threatened destruction and ruin to England in the Elizabethan age. The great historian Fernand Braudel portrayed it as a period of dramatic rise; the Reformation was checked; a new “Mediterranean World” was crafted.

This period produced one great work of literature that ranks ahead of all others. It is the tale of Don Quixote de la Mancha, authored in two parts by Miguel Cervantes. In our literary canon, the novel has come to dominate the other forms in modern times. And with respect to the novel we can say, “in the beginning was Cervantes.” The genre springs from his work. And even today, after four hundred years, how many novels can begin to compete with this one? It is a work of amazing flexibility; it piles layer upon layer of meaning. It can be studied in universities and performed in Broadway musicals. Cervantes’s genius was to be simultaneously great, complex, subtle, and yet packed with immediate popular appeal. Cervantes fills a great panorama and he perfects the art of the tragicomedy. What seems at first blush a farce, a comic send-up, turns into a work filled with pain, loss, horror and introspection. What seems at first shallow soon emerges, especially in the second part, as a work of great philosophical depth; of wit and profound and timeless wisdom.

I have read Don Quixote three times in my life; the last time just now. On each reading, I felt Don Quixote said something to me about life and the times in which I lived. Don’t be consumed in the quest for needful things, it said, the real quest leads inward. Beware of the vanities of the world, the frivolities of human existence. And remember wherever your life takes you, and whatever love you may seek from time to time, the need for kindness and respect, the essential qualities which make human life worth living. Life will bring pain and hardship, but have the disposition to be modest, to learn, to be kind and the edge will come off. Cervantes wants to entertain his readers; but he also wants to reshape them.

But on this last reading I did something I had never done before—I read and listened. And something appeared which I never noticed before, like a message written in invisible ink held to the light. It had to do with Cervantes’s relation to his own society and times, and yet it was timeless. But it seemed especially important for the problems of our world today, a world in which the vision of a golden age of al-Andalus–Andalusia–is gaining in importance across a critical cultural fractureline. It told me what, for Cervantes, was truly the golden age. And it was the lost world of Andalusia. A world of chivalric ideal, truly, but in a very hallowed sense lost to his times. But it was the Spain of al-Andalus. The age when Muslims, Jews and Christians lived side-by-side. The age marked by the palm tree that the last Umayyad prince brought from the legendary palace of Rusafa in Syria, and planted in a courtyard in Cordoba. An era of intellectual brilliance, cultural productivity and greatness which has seen few equals in the history of humankind. An age marked by tolerance, faith and science cultivated in equal measure. Beside this great age, the vast wealth and power that Phillip acquired and promptly squandered was hollow and illusory. Cervantes did not see a Spain of greatness and glory in his own time; he saw a nation which was squandering its legacy and impoverishing its culture. And he was right.

And on the other hand, what does Cervantes condemn? The efforts to suppress the last traces of this ancient greatness and nobility. The suppression of the Moors, the moriscos, the expulsion of the Jews, the tyrannical dominance of a Catholic faith that tightened its grip through fear, hatred and persecution.

In the era of the index and the inquisition, of a gripping authoritarianism anchored in the requirement of a public commitment to orthodox faith, how does Cervantes do this? He leaves the clues, carefully planted throughout the book. He leaves them in plain sight, and he protects himself with plausible deniability at every turn. Don Quixote is a crazy man, after all. (And a tradition in European literature was born: plant difficult truths in the mouths of crazy people). Sometimes of course windmills are just windmills; but other times they are really giants.

Our narrator is a self-deprecating man and a trickster, but he gives us plenty of clues with which to understand him:

The truth is that I am somewhat malicious; I have my roguish tricks for now and then, for I was ever counted more fool than knave for all that, and so indeed I was born and bred. If there were nothing else in me but my religion—for I firmly believe whatever our Holy Roman Catholic Church would have me believe and thus I hate all Jews mortally—so these historians would take pity on me and would spare me in their books. (ii, v, 8)

But of course our narrator does not “hate all Jews,” just as he does not hate, but rather hopes for the rehabilitation of the mudejars (the Muslims who settled in the Christian kingdoms), the conversos who embraced Christianity in order to remain in Spain after the edict of expulsion, the mozarabes, the Arabic-speaking Christians who had assimilated to the Muslim culture of Andalusia. To the contrary, Cervantes longs for the greater days when they lived in peace both in the petty kingdoms, the taifas of Andalusia and in the Christian kingdoms of the north. And these are the ghosts who populate Don Quixote; you can hardly turn a page without finding them. Mind you, it’s necessary on occasion to look at those windmills and understand what they really are.

In writing has he been guided by the greatest of the Andalusian Jews, Musa ibn Maymun or Maimonides? It seems that way to me. Maimonides’s Guide for the Perplexed teaches that the semblance of agreement with a surrounding repressive world could be accepted if that is expedient, but never at the cost of surrendering the internal truth.

Have you never seen a play acted, where kings, emperors, prelates, knights, ladies, and so many other characters, are introduced onto the stage? One acts a ruffian, another a soldier; this man a cheat; and that a merchant; one plays a designing fool, and the other a foolish lover. But when the play has run its course, and the actors disrobe, suddenly they are all equal, as they were before… Just such a comedy, said Don Quixote, is acted on the great stage of our world—a stage upon which some play the emperors, and others the prelates, in short, all the parts which are played in the drama. And then Death creates the catastrophic end of the action, striping the actors of all their marks of distinction, for in death all are made of the same dust and ashes. (ii, v, 12)

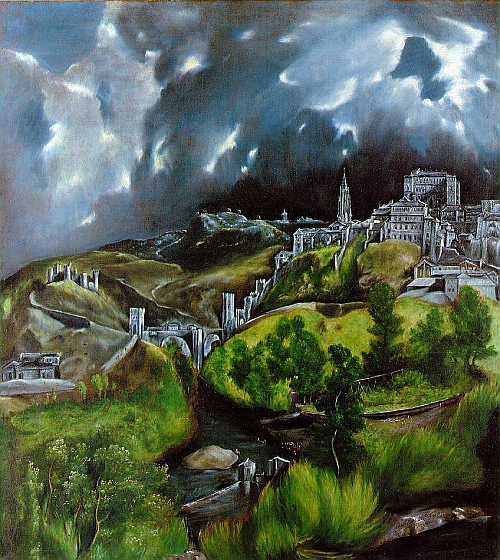

Consider the story that Cervantes relates on the origins of his work (i, ii, 9). He presents us with a very curious conceit. In the Jewish quarter of the old Castilian capital of Toledo, he tells us, he came upon a Moor who was about to sell a curious manuscript to be pulped to create new paper. And this manuscript, we learn, is the tale of Don Quixote, the man of la Mancha, which has been faithfully recorded in Arabic by the chronicler Cid Hamet Benengeli (another typically Cervantean joke, since a reader with some familiarity with Arabic will recognize this means something on the order of “Lord Hamet of the Eggplants.”) So a great work of chivalric exploits of an Arab-bashing Christian Castilian nobleman and his prototypical sidekick is a relic of the Arabic literature of Andalusia? How can that be? And why would Cervantes make it so?

This is not purely a joke, though it would be convenient for Cervantes to be able to dismiss it in such a way. But I think it is not intended to be a delusion. It is a carefully packaged message. The chivalric legacy of the golden past is not wholly a Christian legacy, it tells us. This legacy sprang from the interaction of cultures; from a period of cultural zenith, when Christians, Muslims and Jews found a common language which flourished as the medium of statecraft, art and science. And that language was Arabic. (Cervantes, of course, spoke and wrote Arabic, learned during his four year internment in Algiers. He also had a reasonable exposure to Arabic literature).

But this passage—one of the most amazing in the first part of Don Quixote–brings much more. Throughout Cervantes’s life Spain was undergoing a painful and violent process of ethnic cleansing. King Phillip wanted a new homogenous state, rid of Moors and Jews—a state that embraced a stern Roman Catholicism. And this led to destruction of many important relics of the glorious past of Andalusia in addition to the suppression of Jews and Arabs. The image that Cervantes brings us captures perfectly his horror at what was happening. His masterwork was to have been pulped because it was in Arabic—a reflection of that ancient culture.

And consider: he acquired the manuscript from a Moor in the Jewish quarter of Toledo? He is telling us that he acquired it from a ghost. In 1600, there were no Jews in the Jewish quarter—they had been driven out.

The hidden message also appears in other cavities of the work. And you have to listen to find it. Cervantes fills his work with music—there are songs, romances, ballads, allusions to works which his contemporaries would know, but are not filled out.

But thanks to Jordi Savall, Montserrat Figueras and the Capella Reial de Catalunya, all of this is lost no more. To mark the 400 year anniversary of part I of Don Quixote, the Government of Catalonia commissioned a comprehensive researching and recording of the music to which Cervantes alludes throughout the work. The product, available in two CDs with an accompanying book from AldiaVox, is a revelation.

Much of it underscores that Cervantes’s quest for the past looks to the south, not to the north—it draws very heavily on the morisco and Sephardic musical traditions. A striking example comes in the chapter in which Don Quixote and Sancho Panza arrive in the city of Toboso in their quest for the lady Dulcinea. The language of this chapter opens with amazing juxtapositions of silence and sound, and Cervantes references three different ballads. Of these the most important is the second, which the duo hear being sung by a peasant off in the early morning to the fields (ii, v, 9). The knight and his squire are gripped by this ballad and they are concerned it has some import for them in the following day. The ballad, Cervantes tell us, is the story of a knight named Guarinos and it relates to the battle of Roncesvalles—that is, it is a Carolingian epic, focusing on the decisive defeat the Franks suffered at the hands of the Moors in a Pyrenees mountain pass. The battle is generally taken as marking the triumph and dominance of the Umayyads on the Iberian peninsula; its incorporation into the Islamic world.

But as Savall tells us, this is no imaginary work, the late medieval ballad actually exists. And here is its hypnotic refrain, from the mouth of a Moorish prince, which comes after a recounting of the defeat suffered by the Franks at Roncesvalles:

In the name of Allah, Guarinos, embrace the Muslim faith,

And all manner of worldly riches I will offer you,

And my two lovely daughters henceforth shall be yours,

One to do your bidding as a handmaid at your side;

The other to be your natural bride.

And as a dowry, Guarinos, I shall give you all the cities of Arabia,

And more if you ask it of me.

It is a tale of conversion, by the Moors—a soft and gentle conversion, asked with a hand of friendship. How it contrasted with the Spanish monarchy’s betrayal of its commitment to the Moors of Grenada and with the forced conversions and persecutions that followed. The use of the ballad is the clearest sort of irony. And when he learn more about Dulcinea it becomes even more striking.

This Dulcinea del Toboso, so often mentioned in our history, is said to have the best hand at salting pork of any woman in all of La Mancha. (i, ii, 9)

We learn this from the mysterious Toledo Moor, and Cervantes tells us he is laughing.

The suggestion surely is that Dulcinea herself is a converso and that she is no “lady” at all. The laughing reference to salting pork is the give-away. Culinary historians tell us that in the century after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, the public consumption and curing of pork products emerged as a sort of cult throughout central and southern Spain—it was pursued as a political statement, namely, “I am not a Muslim. I am not a Jew.” And the joke was that those who most enthusiastically embraced the pork trade were conversos, eager to make the point. The name Dulcinea del Toboso itself, of course, is ambiguous, but not something which is clearly Castilian. So the lady who is the object of the quest is a converso, and in the Sufi tradition, with which Cervantes is well familiar, that lost one stands for other things–a lost world, a better connection to humanity, an approximation to God.

All of this leads to questions about Cervantes himself. Did he spring from a converso family? I have no idea, and haven’t researched it, but there is much in Don Quixote that suggests this; at least he sympathizes with the conversos–he rejects their stigmatization.

But there were other scenes that lept out to me on this re-reading. One is the burning of books in the library. In a sense, this is the work of well-intending friends who want to free Don Quixote from the ridiculous world of chivalry with which his mind has become so intoxicated. But is there not something quite wicked about having a curate and a barber browse through a library and pick books to be burned? And again, the barber, at this time, would be a figure who performed minor medical surgeries, an artist in blood and gore. It seems to me that Cervantes sees these two men as the embodiment of the forces of a new Spain, and their intent is perhaps not at all so kindly as appears on the surface. What sly double entendre lies behind lines like this:

Another book was open. It proved to be The Knight of the Cross. The holy title, cried the curate, might in some measure atone for the wickedness of the book. But let us consider the saying: The Devil lurks behind the cross! To the flames with him! (i, i, 6).

In a day when the Holy Inquisition busied itself with exposing conversos whose acceptance of the Cross was suspect, and hurried them to their maker upon a vehicle of fire (the auto da fe), these words have another, darker meaning.

And then we have the master’s wonderful chapter on the laws of war (ii, v, 27), in which we get a fair recounting of the doctrine of Just War. “I swear as a true Catholic,” the narrative begins… though then we recall that the narrator is no Catholic, but a Muslim who has not converted. Cervantes recounts poignantly for the second time the tale of his imprisonment in war, and he pleads for mercy and humanity towards those imprisoned. And his message could not be clearer–he is concerned about war that crosses the lines of faith: not just the campaigns of Catholic Spain against the Protestants of the north (he served as a quartermaster in connection with the Armada), but more importantly conflict with the Muslim world–which is, of course, how he spent his own military career. The balance of the chapter is an admonition. Cervantes warns us against those who pursue war as an act of vanity; who take personal offense as cause for war; who seek prestige and forget the great human cost that war may unleash. Cervantes is no pacifist, of course, he was a professional soldier before he became a writer. He achieved citations for valor in the wars against the Corsairs and the Turks. But he considers war making to be a matter of grave moral judgments. And he condemns harshly those who miss the gravity of it. They become an “army of braying asses” who are whipped into a frenzy by talk of slights and dreams of glory in war. It may be the single bitterest passage of the book. And today, when I turn on my television, I find the army of braying asses are still with us. Braying more loudly than ever.

But for the human being who aspires to be good, the true battle is a battle within:

Since we expect a Christian reward, we must suit our actions to the rules of Christianity. In giants we must kill pride and arrogance. But our greatest foes, and whom we must chiefly combat, are within. Envy we must overcome by generosity and nobleness of spirit; anger, by a reposed and quiet mind; riot and drowsiness, by vigilance and temperance; lasciviousness, by our inviolable fidelity to the mistresses of our thoughts; and sloth, by our indefatigable peregrinations through the universe, to seek occasions of military, as well as Christian honors. This, Sancho, is the road to lasting fame and a good and honorable renown. (ii, v, 7).

Our world and the human condition is immiserated by those who seek always to find the dividing lines between peoples and cultures, who see ultimate virtue in homogeneity and who embrace a creed of intolerance. How much better is humankind served by those who seek to find the golden cord that ties and unites us, that has been a source of inspiration throughout human history. This ultimately is the true quest of the ingenioso hidalgo Don Miguel de Cervantes. The gold and riches of the age of Phillip II and Phillip III passed through the treasury of the Spanish state like so much sand poured through open hands. They were lost with little to show. But this period left Spain and the world with one unsurpassable treasure. And that is the story of Don Quixote.