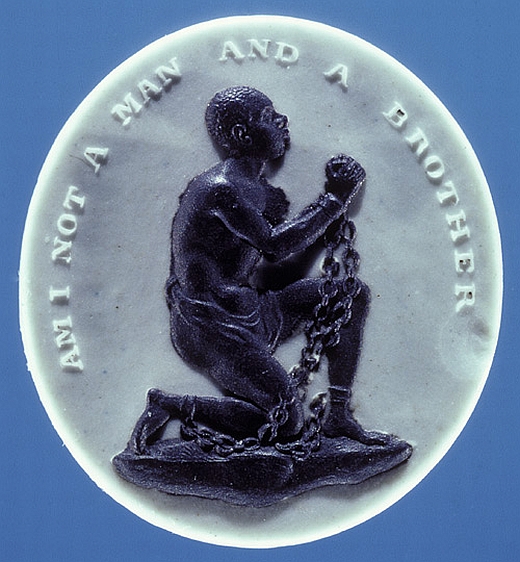

Tomorrow marks the bicentennial of America’s prohibition of the slave trade, one of the last significant legislative acts of the presidency of Thomas Jefferson. The absence of public recognition of this date is disturbing. It reflects a pattern in which international law is steadily denigrated by officials of our Government and by their sustaining chorus of media talking heads. Around the world–outside of the United States–the bicentennial of the abolition of the slave trade has been celebrated and marked with books, speeches, and even an important, feature motion picture. It marks the decisive moment when international law stopped being exclusively about the rights and privileges of princelings amongst themselves, and started being about the fundamental rights of human beings simply because they are human beings. My contribution, “Doing God’s Work,” an essay on William Wilberforce and his foundational role in the global human rights movement can be read here, and will appear shortly in an expanded version in a book edited by Princeton theologian George Hunsinger.

Historian Eric Foner marks the date with an op-ed in the New York Times. Foner’s piece is a must-read. But then, I can’t remember ever having come across something by Foner that wasn’t. He’s got to be the best living serious writer of American history. In fact, I think it’s impossible to understand the American South and modern race relations without having read his seminal works on Reconstruction. Foner explains why the decision to end the slave trade that was taken at Westminster and the law that Jefferson signed had different consequences:

The British campaign against the African slave trade not only launched the modern concern for human rights as an international principle, but today offers a usable past for a society increasingly aware of its multiracial character. It remains a historic chapter of which Britons of all origins can be proud. In the United States, however, slavery not only survived the end of the African trade but embarked on an era of unprecedented expansion. Americans have had to look elsewhere for memories that ameliorate our racial discontents, which helps explain our recent focus on the 19th-century Underground Railroad as an example (widely commemorated and often exaggerated) of blacks and whites working together in a common cause.

Nonetheless, the abolition of the slave trade to the United States is well worth remembering. Only a small fraction (perhaps 5 percent) of the estimated 11 million Africans brought to the New World in the four centuries of the slave trade were destined for the area that became the United States. But in the Colonial era, Southern planters regularly purchased imported slaves, and merchants in New York and New England profited handsomely from the trade.

The American Revolution threw the slave trade and slavery itself into crisis. In the run-up to war, Congress banned the importation of slaves as part of a broader nonimportation policy. During the War of Independence, tens of thousands of slaves escaped to British lines. Many accompanied the British out of the country when peace arrived. Inspired by the ideals of the Revolution, most of the newly independent American states banned the slave trade. But importation resumed to South Carolina and Georgia, which had been occupied by the British during the war and lost the largest number of slaves.

The ideology of slavery became deeply entrenched in America’s south. It also produced a theology of slavery, giving rise to some aberrational offshoots of Evangelical Protestantism that also took root south of the Mason-Dixon Line. It profoundly shaped America’s political consciousness. The slavery ideologues wanted to perpetuate and expand the peculiar institution. They sought a hemispheric system which would be anchored in America’s south: an agrarian society which would rest on slave labor. They embraced a vision of divinely authorized imperial conquest and exploitation. They saw no issues with official cruelty and torture, because indeed these were essential to the maintenance of the slave system. The nation had to be purged with blood to rid itself of this excreable institution. But we delude ourselves in thinking that the purge was complete, for the ghosts of the slavery system and the ideology of slavery can be found all around us today, masquerading under other names, and propelling the same quest for empire and embrace of cruelty.

Each step taken in the effort to repress the institution of slavery and to rectify its abuses was a matter of honor for the American nation. Each step demands that we recall it and the sacrifices that it entailed in the cause of justice and freedom. It also gives us pause to remember one of the most shameful vestiges of our Constitution, which was never a wholly worthy document—namely the notion of slaves as three-fifths humans. It behooves us to remember the wrongs done, and the patriotic efforts of the true American ideologues to overcome them. It behooves us to remember that this struggle continues today, it is not completed.

January 1, 2008: the bicentennial of the abolition of the slave trade by the United States.