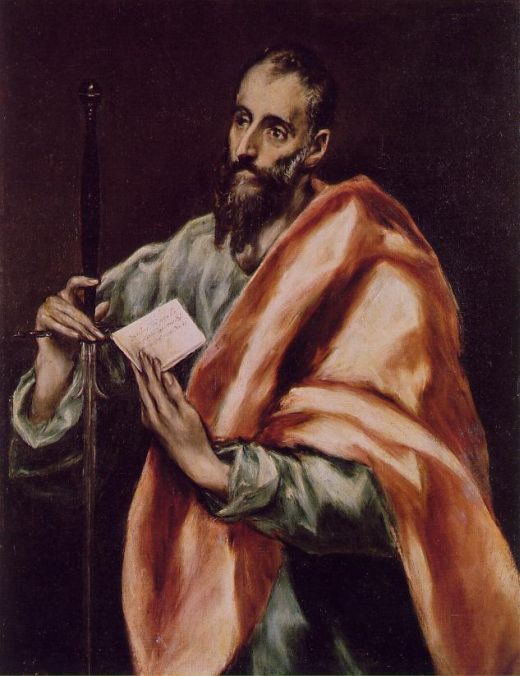

At the end of chapter 22 of the Acts of the Apostles, certainly a vital chapter because of its chronicling of the life of Paul of Tarsus, comes this dramatic passage. I quote it in the language of the King James Bible:

The chief captain commanded him to be brought into the castle, and bade that he should be examined by scourging; that he might know wherefore they cried so against him. And as they bound him with thongs, Paul said unto the centurion that stood by, “Is it lawful for you to scourge a man that is a Roman, and uncondemned?” When the centurion heard that, he went and told the chief captain, saying,

“Take heed what thou doest: for this man is a Roman.” Then the chief captain came, and said unto him, “Tell me, art thou a Roman?” He said, “Yea.”

And the chief captain answered, “With a great sum obtained I this freedom.” And Paul said, “But I was free born.” Then straightway they departed from him which should have examined him: and the chief captain also was afraid, after he knew that he was a Roman, and because he had bound him.

Paul has been seized and he is about to be tortured, but something he discloses saves him from this brutal fate. Actually this is one of the passages where the King James text is, to put it charitably, not a model of clarity. In fact, the mistake it makes undermines the meaning of the entire passage. Repeatedly we are told that Paul is a “Roman,” but of course we know that Paul is not a Roman, he is a Jew, neither has he lived in the city of Rome. What is meant here is something different, namely that he possessed the status of citizen of the Roman Empire. The Greek original says ???????? ??????? but the language of the Vulgate makes the point most clearly, for the words it puts in the centurion’s mouth, and quite plausibly the words he uttered if they were in Latin, are “hic enim homo civis Romanus est,” that is, “this man is a citizen of Rome.” The emphasis falls on the word that the King James text skipped, “citizen.”

Paul has been caught spreading the word of Christ and was imprisoned in Caesarea. He was on the verge of being subjected to what might today be called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” ????? ???????? the text says, torture is to be applied in connection with interrogation. And he stops the process by proclaiming his exalted status as a Roman citizen. He notes that the Roman law forbids the use of torture to interrogate a citizen, and he demands his right to be tried in Rome. But the text gives us a sign that Paul’s meaning is not all technical legalism. Note that when the officer asks him how he came to have the privileges of citizenship, he answers with portentous language. He says, “I was born free.” The question was not whether he was a freeman. It was whether he was a citizen—a very different test of status. Was Paul proclaiming in an innocent way the radical egalitarianism for which some early church fathers were famous? Was he offsetting the claim of privilege of his earlier answer? The words seem to me laden with meaning. But in any event, the assertion of citizenship was, as Acts records, a “show stopper.”

The accounts that remain of Paul’s life are of course fragmentary, and in particular we have no more detail on the legal proceedings against him. Clearly from the perspective of the Romans he was viewed as an instigator connected with a radical and dangerous religious organization. But this story offers some astonishing parallels to the dilemma America faces today. Only today the great empire struggling to maintain order and wielding torture as a tool is America, and the radical religious movement that is caught in the crosshairs and that it seeks to suppress is Islamic. Of course we are linked to that community which formerly suffered persecution and torture at the hands of the Romans, we are their successors. And it behooves us to recall the cord that links us over time.

In our nation, like in the Roman Empire at the time of Christ, a double standard has been erected. In theory, torture is available for use on the “enemy,” but not, in any event, on American citizens. But torture is by its nature both contagious and corrosive, and history knows of many efforts by states to contain it, but none of them have been effective. My friend Darius Rejali from Reed College has a new book out, published by Princeton University Press, called Torture and Democracy. It is a work of superior scholarship, meticulously chronicling the development of torture techniques from antiquity forward. That is the sort of work that a torture museum might present, of course. But Prof. Rejali continues to do something far more difficult. How does torture affect modern democratic societies that use it, he asks. And he starts by asking about their efforts to regulate and control torture.

Few societies had a more carefully charted system of torture than the Romans. They used torture much as President Bush contemplates its use, namely as a tool for interrogating enemies. They specified permitted techniques and detailed who could use it and under what circumstances. They regulated its admissibility as evidence in legal proceedings. They refrained from negative moral judgments about torture, but while embracing its use, they also noted that it really wasn’t particularly effective or useful in extracting information from subjects. The prime rule they devised is the one that Paul relies upon in Acts–they forbade torture to be used against a citizen who was uncondemned. That is to say, torture could be used as a punishment, but not in connection with interrogation.

But Rejali tells us that the barriers and internal rules could not hold. Once torture emerged as a practice authorized by law in some circumstances it spread very quickly, and ultimately the prohibition against torturing citizens could not be sustained. Moreover, he catalogues the appearance of torture and efforts of states to control it over many centuries and in many societies, with impressive chapters on the French in the waning colonial era, the Nazis through World War II, the Soviets from the Bolshevik Revolution, the Communist Chinese, the Iranians from the time of the Shah and after his overthrow, and finally, and most surprisingly, the United States under George W. Bush. There are clear lessons to be drawn from these historical excursions, but the experience of the Romans—the most masterful state-builders of antiquity—really tells us all we need to know. Torture is a virus which cannot be effectively controlled. If permitted at all, it will undermine the integrity and worth of humanity in any society in which it is let loose. It is the ultimate social agent of corrosion.

Those in authority in this country set that agent of corrosion free and they did it secretly, covertly in the months after 9/11. What they did violated the nation’s laws and more importantly, perhaps, our national self-understanding. When their practices were revealed, they reacted by lying about what they did and then scapegoating a number of young soldiers who misbehaved under conditions in which those in authority encouraged them to misbehave. The authors of the torture policy have hidden in the shadows and have manipulated the levers of power to shield themselves from public scrutiny and from accountability in any form. And they have successfully evaded accountability to this day.

The issue of torture continues to boil on Washington’s front burner. It features in a Congressional effort to bind the intelligence community to the specific standards adopted by the Pentagon. Actually, under the Detainee Treatment Act from 2005, they are bound, but of course, the Bush Administration has a secret different understanding. The attorney general, Michael Mukasey, is called to explain his views about waterboarding and other torture techniques before the Senate Judiciary Committee. His performance is an embarrassment to those who know him and spoke highly of him when he was nominated. The most charitable thing that the New York Times could offer was that he was “better than Alberto Gonzales,” which sounds more like an insult than a compliment.

But I think it’s appropriate for us first to take stock of the positive developments, and then note their limitations. It now appears that the American policy of torture will terminate in just over eleven months. I say that because the Republican presidential nominee now seems clear, and the Democratic field has been reduced to two candidates. All of this will become much clearer in about 36 hours, after the votes from Super Tuesday have been tallied. But if things work out as now seems likely, then we can be confident of a significant success. We are now entering into an election campaign in which emotions run high and most of the dialogue will consist of castigation rather than praise of presidential candidates. But I believe that the final field of Clinton, McCain and Obama, consists of three individuals with a strong commitment to public service and, for all the differences which will be highlighted, also a solid set of defining shared values. One of those values shared by all three finalists is a commitment to end torture. That’s why I say that the Bush Administration’s torture policy will end on January 20, 2009.

So why are we here today talking about torture? Shouldn’t we celebrate and move on? I don’t think so. The issues that remain are severe. Let me sketch this out.

First, the Bush Administration’s posture has from the outset been to give the president discretion to authorize torture—it should be his judgment call. The change on the horizon is based on the president’s whim, and it can just as easily change with the next president—and indeed, a president who makes a commitment against torture can renege on it. That happens often enough in our political culture.

The Policy Struggle in Washington

The Bush Administration has labored relentlessly to undermine the legal and constitutional prohibitions on torture. In fact, acceptance of torture has become the key litmus test for its nominees to high legal office. We witnessed this with both Michael Mukasey and his deputy Mark Filip. It appears to me that both were required to profess acceptance of the Bush torture regime as a condition to their appointment. And the same seems now to be commonplace with respect to the Administration’s judicial nominees; we see this in their irrational decisions that turn precedent and common sense on its head in order to cloak official misconduct and protect those involved in the torture system. And most particularly we see it in the dealings surrounding the Office of Legal Counsel, where the original torture memorandum was crafted by John Yoo and Jay Bybee, and now a total of not less than four supplementary torture memoranda have been prepared by Daniel Levin and Steven Bradbury. At some point very soon all these memoranda will be public. But in the meantime we can draw on the judgment of James Comey, who was Alberto Gonzales’s Deputy Attorney General, and who said that when they become public, they will cast a cloud of shame over the Justice Department.

The story of Dan Levin’s involvement with the issue is extremely revealing of how vital all of this is to the president’s inner team. When Levin expressed concern that waterboarding might, as applied in some circumstances, be torture, and declared he was going to draft a memorandum setting out the exact rules governing waterboarding, he was immediately removed from office and replaced by a more pliant political hack, Mr. Bradbury. We learn that Vice President Cheney’s chief of staff and Attorney General Gonzales were intimately engaged with this entire process. All of this shows the talismanic significance of the torture issue to Team Bush.

The Struggle for a Nation’s Conscience

But second, we need to remember that the battle over torture is not merely a struggle for the formulation of legislation and policy in Washington. It is a struggle for the soul of a nation. The Bush Administration’s pursuit of torture is not limited to Langley and the CIA black sites, it is also over the airwaves and through the cable boxes that reach into almost every American household. As Human Rights First’s Primetime Torture project has shown, after 9/11, the incidence of torture in entertainment programming has skyrocketed. The big offender is one particular network, the same one which floods the airwaves with softcore pornography in the guise of reporting which “condemns” it. And the single program which has done the most to champion torture is “24,” an adrenaline-packed show in which torture occurs every day.

In American popular culture, torture used to be something that was done by the Nazis, by the Soviets and Chinese in the Cold War. Americans were its victims, always standing steadfast against the evil that it embodied. But in the Fox Network vision of torture, Americans use it, they do so for patriotic purposes—to save thousands from attacks which would occur were torture not used—and, wondrous to relate, torture always works. So torture is now the favorite tool of the good guys. There is absolutely nothing coincidental about this. As Jane Mayer revealed in her article “Whatever It Takes,” published last February year in the New Yorker, this plot thread has been quite consciously crafted by Fox as a little boost for their friends in the White House. Dick Cheney and David Addington needed some help overcoming 230 years of American culture, starting with George Washington. Before George W. Bush, American presidents had been consistent in saying that torture was wrong and that America would never use it. So Fox sprang to their aid.

Two centuries of American history went down the rat hole. And in its place: Enter Jack Bauer, the all-American hero. He tortures with gusto, and he saves the American people at least a couple of times every season. Torture is an indispensable part of his act. The series also gives us a new enemy. We have, of course, the vaguely Middle Eastern Islamic terrorist, the current Hollywood staple figure. But now we also have the naïve liberals who oppose torture and whose attitudes will cost thousands of lives if they aren’t checked. America’s security demands that we keep these people away from Congress and Government; if they have their way, and torture is banned again, thousands of innocent Americans will die.

A False Choice

What’s missing from these accounts? For one thing the fact that the ticking-bomb scenario upon which they build has never occurred in the entirety of human history. It’s a malicious fiction. For another the fact that torture, when applied, seems very likely to produce false intelligence upon which we rely to our own detriment. Ask Colin Powell. He delivered a key presentation to the Security Council in which he made the case for war against Iraq. The keystone of Powell’s presentation turned on evidence taken from a man named al-Libi who was tortured and said that Iraq was busily at work on an WMD program. This information, of course, was totally wrong. Al-Libi fabricated it because he knew this is just what the interrogators wanted to hear, and by saying it, they would stop torturing. It was a perfect demonstration of the tendency of torture to contaminate the intelligence gathering process with bogus data. And for Powell, it was “the most embarrassing day of my life.”

And still, this is just the beginning. Generations of Americans have fought and sacrificed to build a system of alliances around the world that provide our security bulwark. What has happened to those alliances? In country after country—including many of the nations which have historically been our tightest allies–our government’s approval level is within the margin of error. That’s right. The percentage approving may actually be zero. In nation after nation and even among our own allies, we are outstripped by the world’s last Stalinist power, China. This is a very heavy price, and most of it has to do with torture policy.

And the weightiest link in this chain tied around our national neck should be considered last. As my friend Mark Danner writes, if you assembled a team of Madison Avenue’s most brilliant thinkers in a room and asked them to concoct a recruitment plan for al Qaeda and its allies, we’d never come anywhere close to the one that the Bush Administration delivered up to them with the torture program. It’s the major reason why today, six years after the start of the war on terror, al Qaeda is back up to the strength it had on 9/11, and the Taliban has also been able to regroup and recharge, destabilizing a friendly government in Afghanistan.

Torture is a Moral Issue

But I have reviewed torture from the perspective of rational choice, on the basis of efficacy alone. And I hardly need to say before this audience that torture is a moral issue. Torture is the legacy of the darkest era of mankind’s history. It took a steady struggle over centuries to overcome it. We need to take stock of that history, and here and today we should especially recall the essential role that the community of the faithful played in that process. The historical facts should give us courage in what we face today, for surely the obstacles in our path are less than our forefathers faced.

The Road Up From Torture

Rick Ufford-Chase spoke to us yesterday of the fear that many ministers have of even uttering the word “torture.” It’s a politically divisive issue, a volatile issue. How does a minister raise the question without angering a part of his congregation? Indeed, it requires courage to do so.

But we need to start by rejecting the idea that this issue is political and thus taboo. In fact it is ultimately and must be viewed as a moral issue on which the church’s teachings are clear. And on this point we should take comfort in the path that people of faith pursued before us.

For hundreds of years, torture was an accepted, perfectly ordinary practice—a part of the justice system. The genius of the English law was to circumscribe, to limit it. By the time of the Tudor monarchs, only the monarch or a judge could authorize torture, and its use was carefully tracked and recorded. But with the arrival of the age of religious conflict—roughly the mid-sixteenth through the mid-seventeenth century—its use surged once more. It was applied against whoever failed to subscribe to the state faith: against dissenters, against Calvinists, but especially against Catholics, who were the community then most under suspicion of harboring, collaborating with and being terrorists. Prominent Catholics were routinely arrested and questioned to find out who they knew and with whom they met, and a meeting with the wrong sorts could provide an opportunity for an appointment with the rack or even the executioner.

We shouldn’t think the controversy about torture was purely a matter for the lawyers and politicians. It was in the end an issue in which the community of the faithful played a decisive role.

John Donne’s Role

And one man merits a pause and acknowledgement in this process. His name is John Donne. We know Donne today of course as a poet, the author of powerful metaphysical verse. But Donne was a clergyman, in fact the dean of St Paul’s in London, the first church in the land. He came from a prominent Catholic family which faced terrible persecution in the time of religious turmoil. Members of his family were imprisoned, beaten and at least one—his brother Henry–was cruelly tortured, using the implements of the day. Donne, choosing the path of least resistance, became an Anglican, although the depth of his conversion to the Protestant cause is still a matter of some debate. Let’s just say that Donne was a Christian possessed of a strongly ecumenical spirit.

But he felt very bitterly about torture. He saw in it an evil rotting away in the core of his society. It was an intrinsic evil, which could never be justified. Several of his poems refer to “torture,” most importantly “Love’s Exchange.” Most of the Donne scholarship sees “torture” as it appears in this poem as a metaphor, the agony of unrequited love. As I have argued elsewhere this limited understanding is certainly a misreading. It is a deadly earnest poem and Donne is, in fact, referring to torture just as it was practiced in the late Elizabethan, early Stuart period. He writes, in the most jarring language to appear in any Donne sonnet:

To future Rebells; If th’ unborne

Must learne, by my being cut up, and torne:

Kill and dissect me, Love; for this

Torture against thine owne end is,

Rack’t carcasses make ill Anatomies.

Donne’s message here couldn’t be clearer: torture is not an effective tool. It stokes the passion and anger of the opponent. But more importantly, “torture against thine owne end is,” it is a mortal sin. These lines stand in Donne’s verse. But they also appear in his theological works.

With time, Donne grew braver in his criticism. In the last week of March 1625, King James I died, and his son Charles succeeded him to the throne. The king’s men let it be known that he was looking for a new minister at Whitehall, and that the post might be Donne’s. His sermons were being observed. The king of course had High Church leanings and a Catholic wife, and he let it be known that the prospect of having the Anglo-Catholic Donne as his minister appealed to him. Donne decided he had the audience he wanted, and on Easter Sunday, April 17, 1625—the most important day of the liturgical year for a preacher and a day on which he knew his suitability for royal favor was being tested–Donne delivered what must be reckoned one of his greatest sermons. It was against the abomination of torture. The practices of torture, he said, were an intrinsic evil and always wrong. He did not criticize the king directly, but he assailed the king’s judges who issued torture warrants, saying that by doing so they revealed not strength but weakness. He said:

They therefore oppose God in his purpose of dignifying the body of man, first who violate, and mangle this body, which is the organ in which God breathes, and they also which pollute and defile this body, in which Christ Jesus is apparelled; and they likewise who prophane this body, which is the Holy Ghost, and the high Priest, inhabits, and consecrates.

Transgressors that put God’s organ out of tune, that discompose and tear the body of man with violence, are those inhuman persecutors who with racks and tortures and prisons and fires and exquisite inquisitions throw down the bodies of the true God’s servants to the idolatrous worship of their imaginary gods, that torture men into Hell and carry them through the inquisition into damnation. . .

I am quoting only a small part of the sermon, which ran to nearly two hours duration and included critical discussion of the Roman legal glossator Ulpian and a critique of St Augustin for his indulgence of torture.

Understandably, of course, Donne did not get the appointment at Whitehall. I don’t think he really wanted it. At this stage in his life, at least, Donne was more interested in the Word than in wealth and proximity to power. He wanted to send a message against torture. The sermon he preached electrified the nation and did much to help sharpen attitudes against torture, especially within the religious community.

What effect did his sermon have? This requires some speculation, but it’s very clear than in the years immediately after it the king and the judiciary began to see torture in a different light. But those of you who have read Alexandre Dumas and his Three Musketeers will know some of the story that follows, for Dumas frames his tale on historic facts. In 1627, the king’s favorite, the Duke of Buckingham, led a disastrous English military campaign to relieve the besieged Calvinist city of La Rochelle on the French Atlantic coast. Shortly after his return to England in 1628, Buckingham was assassinated. His knife-wielding assailant was captured, and the king was approached for a warrant to authorize his interrogation under torture. They had been routinely issued in the past. But King Charles choked at the request; there is little doubt that Donne’s sermon had a lot to do with his hesitancy. Instead of granting the warrant, the king directed that the judges of England assemble at the Inns of Court in England and render him advice. Was the torture of a suspect in connection with interrogation to be permitted by the laws of England, the monarch asked. And Blackstone records the result. The judges assembled, deliberated and issued their declaration. “Upon their honour and the honour of England,” they said, torture was against the common law. That marked the beginning of the sunset of legally sanctioned torture in the English-speaking world.

America has had no lengthy historical debate over torture because the prohibition against torture was our birthright. It was anchored in the English law before our nation was even founded, but the Framers of our Republic used the prohibition of torture as an issue by which we defined ourselves. Torture was the tool of an autocratic or despotic state, they said, no democracy would allow it. George Washington was emphatic in prohibiting it, issuing standing orders for the punishment of any soldier who mistreated a prisoner. In fact, Washington said that the death penalty might be a suitable punishment for a soldier who abuses a prisoner, and he likewise prescribed harsh treatment for any soldier who mocked or denigrated the religious beliefs of a prisoner. The current George W. has entirely different ideas, of course.

But my message to you is simple. Remember the courage that John Donne mustered in speaking out. He spoke from the heart and he spoke from the need to make plain to his audience that the church could not be indifferent to torture as a practice. This is a model for emulation today. Can the community of the faithful make a difference on this issue? Yes, they can. They must.

Prepared remarks delivered to a conference of the Presbyterian Church, “Torture, Terror and Security,” at Columbia Theological Seminary, Decatur, Georgia, February 4, 2008.