On Valentine’s Day the Bush Administration was out on a mission, straight from the Orwellian Ministry of Love. That ministry of course served in Nineteen Eighty-Four as the center for torture. And as the shortest month reached its middle point, three apologists appeared on behalf of the administration to explain to the American public that they needed to relax and start getting comfortable with torture. It’s the new American Way, after all.

Act One: We Do It Better Than the Inquisition

The first appearance was by Steven G. Bradbury, who now heads the Office of Legal Counsel in the Justice Department. As ABC News, the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times collectively uncovered, Bradbury owes his rise to a position of power due to one single issue: waterboarding. His predecessor, Dan Levin, was reviewing the universally reviled torture memoranda written by John Yoo, and decided to go to a near-by military base and undergo waterboarding himself to understand better what it was about. He was astonished at what he discovered and concluded that it could not possibly be given a free check. He set out to write a new memorandum putting tight collars on waterboarding. But when David Addington and Alberto Gonzales got word of what he was up to, they acted swiftly. Dan Levin was forced out of his job, and the search began for a new figure who could be counted upon absolutely to protect the torture regime. Steve Bradbury was that man.

If we had to pick just one brief snippet that sums up the corruption that the Bush Administration has worked inside of the Justice Department—its literal transformation from an institution that upholds the Rule of Law to one that spitefully tramples upon it—then it might well be this. Take a few minutes to listen to Bradbury’s evasions, dissembling and his attempts to justify waterboarding with historical comparisons.

And here’s the core of Bradbury’s legal reasoning. In his view, a coercive technique is not torture if it is:

subject to strict safeguards, limitations and conditions, [it] does not involve severe physical pain or severe physical suffering — and severe physical suffering, we said on our December 2004 Opinion, has to take account of both the intensity of the discomfort or distress involved, and the duration, and something can be quite distressing or comfortable, even frightening, [but] if it doesn’t involve severe physical pain, and it doesn’t last very long, it may not constitute severe physical suffering. That would be the analysis.

So the key is brevity. Do it in a few seconds, no lasting effects, and it’s fine. And that’s the beauty of waterboarding, in Bradbury’s mind. A former OLC attorney advisor, Georgetown Prof. Martin Lederman says this is “flatly, 100% wrong, and indefensible.” I’d say that is a charitable characterization. My own view is that this opinion constitutes evidence of Bradbury’s participation in a criminal conspiracy to introduce a regime of torture as defined in American and international law. The law may provide defenses for the interrogators who act in misplaced reliance on the Justice Department’s opinions, but it provides no shield for those who in bad faith formulate the policies that foment torture. Bradbury has no business serving in the Justice Department or in any other public office. He should now be the target of a criminal investigation, together with the other policy-level figures who drove the introduction and propagation of this torture regime. Indeed, beyond their essential criminality, no group of people have done more in the last seven years to undermine the security of every American citizen than these shadowy, ethically-challenged figures who seem propelled by the credo that they stand above the law because they can twist it to say whatever they want.

As for Bradbury’s future career, I suggest he take up acting. He is a natural to play the Grand Inquisitor in Schiller’s Don Carlos or Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov–he has the reasoning down pat, he actually looks sincere and clean-cut as he explains that “torture is good for you.” Our use of waterboarding is humane compared to the Spanish Inquisition, he says. And then he demonstrates the key distinction: the Japanese or Spanish would fill the stomach with water and then stand on the body. For the American version, we fill the lungs with water and don’t do any standing. You can exhale now. Isn’t that a great relief? It’s a kinder, gentler form of waterboarding. A waterboarding of which all Americans can be proud. A waterboarding that reflects America’s core values of respect for human dignity.

It would be good for Bradbury to play this back so he can listen to the absurdity of his statements. Maybe he’ll get the opportunity to hear himself on tape in legal proceedings in the future.

Now we should be clear, Bradbury says that waterboarding today would be illegal. That’s because it’s not a part of the program that President Bush currently authorizes. But waterboarding in the past was perfectly legal, because Bush authorized it and his department approved it. And waterboarding in the future? Well, it may or may not be legal. He’s not saying. He’d have to think about it. How’s that for legal sophistry? Actually, based on Bradbury’s performance to date, there’s no reason to doubt how Bradbury would handle a request from the White House to authorize waterboarding. He will authorize it. Of course he’s not sure now how he will rationalize it, but he will come up with something. He’s that kind of lawyer.

But we shouldn’t give Bradbury a pass on the substance. His arguments can’t be squared with the statute and his description of the “American style” of waterboarding is at odds with the very graphic descriptions provided by U.S. service personnel who have been through the SERE program waterboarding which Bradbury acknowledges is the basis for the technique. It is drowning, not simulated drowning, and it is designed to bring the victim to the point of death, and then bring him back. So Bradbury’s denials of these points are simply lies, and lies to Congress, under oath.

Given the hand he plays, it is now a matter of some urgency that the Senate Judiciary Committee disapprove Bradbury as head of OLC. Indeed, his presence there stains the office and the institution. But it’s also vital that the opinions he authored on national security matters be carefully scrutinized by the Judiciary Committees so that remedial measures can be taken to overturn views that violate the criminal law and international obligations—and his Valentine’s Day appearance suggests that they will be very numerous.

Act Two: Be Very Afraid and Embrace Torture

It’s hard to imagine how the Bradbury appearance could be upstaged. But it was very quickly, by his boss’s boss, the Decider himself. George W. Bush has come under heavy criticism by the Government of Gordon Brown. Whereas the Blair Government had used private diplomacy in its efforts to push the Bush Administration to change its policies on torture and conditions of detention, Gordon Brown has authorized open criticism. Indeed, the U.S. treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo and the plans for Military Commissions have come under direct attack. Bush decided to defend himself in an extended Valentine’s Day interview with the BBC. Pride of place in his comments went to waterboarding, which Bush enthusiastically embraced. Here’s the summary provided by The Guardian:

But his most controversial remarks were over waterboarding. He told the BBC’s Matt Frei: “To the critics, I ask them this: when we, within the law, interrogate and get information that protects ourselves and possibly others in other nations to prevent attacks, which attack would they have hoped that we wouldn’t have prevented?

“And so, the United States will act within the law. We’ll make sure professionals have the tools necessary to do their job within the law.” He claimed the families of victims of the July 7 terror attacks in London would understand his position. “I suspect the families of those victims understand the nature of killers. What people gotta understand is that we’ll make decisions based upon law. We’re a nation of law. . .”

In the BBC interview, Bush was asked whether, given waterboarding and other alleged human rights abuses, he could claim the US still occupied the moral high ground. He replied: “Absolutely.” He added: “We believe in human rights and human dignity. We believe in the human condition. We believe in freedom. And we’re willing to take the lead. We’re willing to ask nations to do hard things. We’re willing to accept responsibilities. And – yeah, no question in my mind, it’s a nation that’s a force for good. “And history will judge the decisions made during this period of time as necessary decisions.”

So Bush’s position is clear: torture is a legitimate tool in the hands of a power fighting from the moral highground. Without wading into the moral dimensions of this problem, we should start by noting that this is the man who has spent five years stating in a mantra-like fashion, “We do not torture.” That statement was untrue, and he knew it was untrue when he first uttered it. Therefore, we can conclude that Bush also believes that a power can lie to its own people and the world about the weightiest subjects—like reasons for war, and the use of torture—and maintain the moral highground. In purely relative terms, he’s right—the Bush Administration maintains a moral high ground vis-à-vis al Qaeda. But it has slouched closer to the morals of its terrorist adversary than any global observer ever would have thought possible.

But the next point to consider is, again without considering the underlying ethical considerations, whether the global community agrees with his statement. After all, the objective of holding the “moral high ground” is to have the support of world opinion behind us. The Founding Fathers recognized that as a vital weapon and they did much to hold it. And in America’s successful campaigns abroad, it has followed the same course. But Bush has fatefully parted from it. Public opinion polling shows that even in America’s key allies—nations like Britain, Germany, Spain, Italy, France, Turkey and Japan—the force of public opinion is not with the Bush Administration. Indeed, he is reviled, and public opinion impedes the ability of those governments to cooperate with the United States. What does this mean practically? The cost of conflicts abroad is dramatically escalated because they are borne by the United States and not shared. And the security of the United States is directly undermined due to the corrosion of these vital alliances, that generations of Americans fought and sacrificed to create.

But then we come to Bush’s core message. He argues that because British citizens were killed in attacks on July 7, the Government should be freed from the constraints of law and given license to torture. Bush’s vision of the world is influenced more by Rambo and Chuck Norris movies than travel or understanding of international relations theory. In his pathetic bubble world, he is convinced, torture is the answer to our problems. But the British response to July 7 was a model for Americans to observe and follow, for in fact, the British, eschewing torture and brutal methods and appealing for public support and alertness, did a far better job than their U.S. counterparts. Darius Rejali makes the key point here:

research has shown that public cooperation is the key to solving crimes –and the public must be confident in the police to come forward with good information. No parent would hand over his child knowing he would be tortured. Cracking a terror cell is not unlike infiltrating organized crime. The trick is to cultivate informers in communities where terrorists operate. Technology is no substitute for this. Nor is torture. Torturing for information destroys bonds of loyalty that keep information flowing, causing remaining sources of information to dry up.

On their own, police are relatively helpless against criminals and terrorists. Since the 1970s, researchers have shown again and again that unless the public specifically identifies suspects to the police, the chances that a crime will be solved falls to about 10 percent. Contrary to popular evening police television shows, only a small percentage of crimes are solved with fingerprinting, forensics and DNA sampling. In England, this constitutes as little as 5% of all detections.

Police captured the 21 July bombers using accurate public information. Tanya Wright, Ibrahim’s neighbor, helped the police locate Ibrahim and a second suspect, Yasin Hassan Omar, on July 22. Police then traced Omar to Birmingham where he was arrested six days later. Police arrested a third bomb suspect, Ramsi Muhammad, in the same flat as Omar. Three commuters had followed Muhammad through London until they lost him. Police identified Hussein Osman, the fourth bomber, by releasing video surveillance. They tapped his brother in law’s phone and Italian authorities arrested him. Police captured their suspects without torture or an American-style Patriot Act.

But Bush’s mind is never very subtle. He believes in himself and he believes the accretion of power in his hands will benefit everyone. Such thinking is of course the classic pattern of tyrannical megalomania. And Edmund Burke was clear about the essential role of fear-mongering in the tyrant’s desire to accumulate power. Appeals to fear are designed not to create alert citizens, mindful of their duties to one another, but quaking bowls of jelly, happy to cede all rights and powers to the man Plato called the “protector,” who soon enough will whip the chariot of State over the bodies of a once-proud citizenry. Or as a friend of mine puts it, “Prof. Shklar at Harvard once remarked, that those who put cruelty first in their lives are especially vulnerable to the vice of misanthropy.” And that we see to full effect today.

Act Three: The Jester

Any well composed classical opera buffa brings us the crude, blundering sort of comic relief. The figure who wants to be one of the big guys, serious, but is a simple figure of derision. The Hofnarr, they call him, the jester. And our Valentine’s Day jester was Senator Lieberman. Here’s what the senator from Connecticut had to say in a phone conference with reporters:

The difference, he said, is that waterboarding is mostly psychological and there is no permanent physical damage. “It is not like putting burning coals on people’s bodies. The person is in no real danger. The impact is psychological,” Lieberman said. Lieberman said that his position on waterboarding differs from that of Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., who he has endorsed as a presidential candidate. As a prisoner-of-war in Vietnam, McCain was tortured. McCain, he said, believes waterboarding is torture.

But Lieberman’s statement demonstrates that he doesn’t understand what waterboarding is all about. Here is a summary by Darius Rejali of the four most prevalent forms of waterboarding.

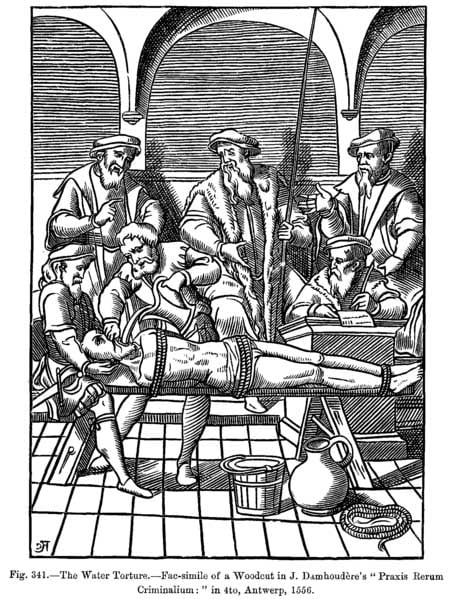

(a) pumping: filling a stomach with water causes the organs to distend, a sensation compared often with having your organs set on fire from the inside. This was the Tormenta de Toca favored by the Inquisition and featured on your website photo. The French in Algeria called in the tube or tuyau after the hose they forced into the mouth to fill the organs.

(b) choking – as in sticking a head in a barrel. It is a form of near asphyxiation but it also produces the same burning sensation through all the water a prisoner involuntarily ingests. This is the example illustrated in the Battle of Algiers movie, a technique called the sauccisson or the submarine in Latin America. Prisoners describe their chests swelling to the size of barrels at which point a guard would stomp on the stomach forcing the water to move in the opposite direction.

(c) choking – as in attaching a person to a board and dipping the board into water. This was my understanding of what waterboarding was from the initial reports. The use of a board was stylistically most closely associated with the work of a Nazi political interrogator by the name of Ludwig Ramdor who worked at Ravensbruck camp. Ramdor was tried before the British Military Court Martial at Hamburg (May 1946 to March 1947) on charges for subjecting women to this torture, subjecting another woman to drugs for interrogation, and subjecting a third to starvation and high pressure showers. He was found guilty and executed by the Allies in 1947.

(d) choking – as in forcing someone to lie down, tying them down, then putting a cloth over the mouth, and then choking the prisoner by soaking the cloth. This also forces ingestion of water. It was invented by the Dutch in the East Indies in the 16th century, as a form of torture for English traders. More recently it was common in the American south, especially in police stations, in the 1920s, as documented in the famous Wickersham Report of the American Bar Association (The Report on Lawlessness in Law Enforcement, 1931), compiling instances of police torture throughout the United States.

The forms of waterboarding used by the CIA today come extreme close to the last two techniques described above. They involve actual drowning—not the “sensation of drowning”—and the statement that there is “no real danger” reflects consummate stupidity. Indeed, the victim will drown absent intervention to revive him, and “accidental” killings involving this technique are fairly commonplace.

Back in 2005-06, when I was working with Senator McCain’s staff on an effort to enact the Detainee Treatment Act, designed to overturn the use of torture techniques, one of his senior staffers told me “Much as Senator McCain likes and respects Lieberman, we absolutely cannot trust Lieberman on this issue. He’s a real snake in the grass.” Truer words were never uttered.

But there’s another aspect of Lieberman’s statement which needs some attention. He presents his rationale as an outtake from the Fox Network’s “24,” he talks about ticking bombs and the urgent needs to wrestle information from a participant in a plot in the course of performance. But of course, not a one of the instances in which waterboarding was actually applied related to anything like such a scenario.

Indeed, a Judiciary Committee staffer who carefully tracked Bradbury’s testimony earlier in the day drew this conclusion from it: “This is an official acknowledgment that we do not use these tactics only in (fanciful) ‘ticking bomb’ scenarios — we use them to find about ‘potential’ ‘planning’ of attacks and enemy ‘whereabouts’ — that’s just general intelligence gathering.” That’s precisely correct and it demonstrates the fraudulent way the “ticking bomb” argument is being used. Students of moral philosophy of course will recognize the technique. It was put forward by Sophists in the post-Platonic period. They suggested that they could contrive a set of facts sufficient to topple any moral law that a moral philosopher could postulate. The “plank of Carneades” is a prime example of their approach comstructed by the Sophists from a teaching of the second century BCE skeptic Carneades. It suggested that in extremis, a person could violate most natural and moral laws to save himself. Carneades did not actually believe this, he presented it as an example of a powerful and malicious form of argumentation with strong appeal to the weak-minded against which society must ever be on guard. And the “ticking bomb” scenario is merely an updated version of this line of reasoning. The way to approach such arguments entails a series of questions:

(1) Has the factual scenario that is posited ever occurred? Is it likely to occur?

(2) What is the consequence to society of taking the exception as a basis for overturning the general rule? How is the exception granted and applied?

(3) What is the objective of those advancing the exception?

However, this approach suggests we treat Lieberman’s comments as something serious and worthy of analysis. In fact the man is not a serious figure and his argument—that “waterboarding is better than placing burning coals on the flesh”—is simply ludicrous, and that’s the best way to treat it.

In the end, Lieberman’s comments add nothing to the debate. But they tell us much about Lieberman.