In the last eighteen months, Antonin Scalia, one of the most influential judges in American history, has twice suggested that he would turn to a fictional television character named Jack Bauer to resolve legal questions about torture. The first time was in a speech in Canada, and the second, only three weeks ago, in an interview with the BBC. This is evidence of the unprecedented influence of a television program on one of the most important legal policy issues before our country today. And it is, or should be, very troubling.

Most of our discussion of torture has focused on the arena of policy formation and debate. We have seen the issues tackled from the perspectives of the law, of ethics and from a utilitarian stance. That is, we have had a focus on the discussion which has occurred in Washington, within the upper echelons of Government, the courts, Congress, major think tanks and the academy. But in this process we are ignoring the forum in which public opinion on these questions may well be settled: namely, in the broadcast media.

Of course, one of the most pervasive memes of our modern political experience has been the notion of the “liberal media,” namely that key figures in broadcast and print media are more liberal than the average American, and that news and entertainment reflect their “liberal” bias. The torture issue provides an interesting opportunity to test this thesis. My view is that the Administration has had tremendous impact on coverage of the issue. It was able to transform well-settled media views.

There are two aspects to this industry that I want to address today—first, news and second entertainment, though there is a rather nebulous middle ground of infotainment. But I want to come to a focus on the entertainment side, where the most serious issues exist.

Torture in the News

News coverage of the torture issue began in proper terms after the publication of the Abu Ghraib photographs. There were a handful of reports that predated this, such as notice of the first two deaths in Bagram Air Base. At the time that the Abu Ghraib photographs appeared, I had completed a major study for the NYC Bar Association looking into legal standards governing interrogation practices. This study had been directly inspired by information the Bar had received from its JAG members to the effect that unlawful torture techniques were being used. Specifically, the following techniques were the focus of our concern: waterboarding, long-time standing, hypothermia, sleep deprivation in excess of two days, the use of psychotropic drugs and the sensory deprivation/sensory overload techniques first developed for the CIA at McGill University. Each of these techniques has a long history. Each had historically been condemned as “torture” by the United States when used by other nations. Each was clearly prohibited under the prior U.S. Army Field Manual. And each was now being used.

I discovered that when I gave interviews to major media on this subject, any time I used the word “torture” with reference to these techniques, the interview passage would not be used. At one point I was informed by a cable news network that “we put this on international, because we can’t use that word on the domestic feed.” “That word” was torture. I was coached or told that the words “coercive interrogation technique” were fine, but “torture” was a red light. Why? The Administration objected vehemently to the use of this word. After all, President Bush has gone before the cameras and stated more than three dozen times “We do not torture.” By using the T-word, I was told, I was challenging the honesty of the president. You just couldn’t do that.

In early 2005, I took a bit of time to go through one newspaper—The New York Times—to examine its use of the word “torture”. I found that the word “torture” was regularly used to described a neighbor who played his stereo too loud, or some similar minor nuisance. Also the word “torture” could be used routinely to describe techniques used by foreign powers which were hostile to the United States. But the style rule seemed very clear: it could not be used in reporting associated with anything the Bush Administration was doing.

In response to the scandal that Abu Ghraib produced, the Administration attempted a new gambit. It could be simply summarized as “scapegoat the grunts.” Unnamed Defense Department spokesmen spoke on a not-for-attribution basis to Pentagon reporters in the weeks after the New Yorker’s and 60 Minutes’ publication of photographs. The unit involved was, we were told, a bunch of uneducated hillbillies from Appalachia, and economic circumstances led the Army increasingly to reach down low to bring in people with dubious backgrounds. A formal review was prepared by a team headed by former DOD Secretary James Schlesinger, which stated that all of the trouble was due to “animal house on the nightshift,” a phrase which mysteriously cropped up several days before the release of the report on a number of right-wing radio talk programs.

Of course, Schlesinger’s formulation which was spread all across the media, was at odds with the report itself, which clearly linked the problems to policies authorized and implemented by the Secretary of Defense. Schlesinger was being used as part of a formal disinformation campaign which was aggressively peddled in the media. By and large it was not believed, but it provided a sufficient cover for the Administration to hold on to it’s “base” of the most Conservative 40% of American voters, and saw Bush and Cheney through the 2004 elections.

I worked with Alex Gibney, Sid Blumenthal and others in the preparation of “Taxi to the Dark Side” and I appear in the film. The objective of this exercise was to clarify in a definitive way how policies which were settled in the secretive inner sanctum of Washington defense and national security establishment were implemented in the field, and how the Administration attempted—largely through a series of rather staggering deceits—to cover this up. “Taxi” intentionally does not start with Abu Ghraib, but rather with the case of Dilawar, an Afghan taxi driver who was falsely arrested, imprisoned and brutally tortured to death. His handling was start to finish in accordance with formally approved Bush Administration policies. The film then traces the flow of these practices to and from Abu Ghraib, Camp Cropper and Guantánamo, and the flood of official disinformation about them. This film was prepared at the highest levels of objectivity and professionalism and the key figures who carry the dialogue are Bush Administration actors – Alberto Mora, Larry Wilkerson, John Yoo and the prison guards themselves, for instance. In one video segment, a senior U.S. officer in Afghanistan speaks candidly about the orders from the Pentagon to use the brutal techniques, and to mislead about their use. We also see how a fake death certificate was issued for Dilawar and then we slowly develop the actual course of events leading to his death. More than one hundred detainees have now died in U.S. captivity, and a large part of those deaths are linked to the use of torture and other brutal interrogation techniques.

When “Taxi” was done, it was shown to broad acclaim at the Tribeca Film Festival, where it was recognized as best documentary. Discovery expressed a strong interest in the product and stepped up to acquire it. Then strange things started happening. The MPAA raised objections to the poster for the film because it showed a prisoner who was hooded, which is of course the standard practice for the US in transporting prisoners. MPAA said it had ethical reservations about showing a prisoner with a hood, that this suggested torture or abuse, and was inappropriate. Of course, that was the exact point. This was a documentary, not an entertainment piece. After weeks of wrangling the MPAA receded. Then we learned that Discovery, which had talked about transmission of the film in the spring, had decided to simply put it on the shelf. The film was “too controversial,” they said. What they meant was that the White House would take offense from it.

There was a loud public outcry over this act of censorship, and the film was flipped to HBO, which will now broadcast it. When this is transmitted, American audiences will see for the first time, comprehensively, how the Bush Administration consciously introduced torture techniques in American prisons – and how it consciously lied about what it did.

The story of “Taxi” shows the sort of problems faced by anyone who wants to present an accurate and candid portrait of the Bush Administration’s policies of official cruelty. But the entertainment side of the ledger is even more disturbing.

The Legacy

We should start by taking a step back in time. The theme of torture is nothing new to Hollywood, of course, it has appeared in many forms, frequently in romanticized historical settings. But when it makes its appearance in connection with contemporary settings there are some consistent themes. As the World War II era propaganda poster says “Torture—The Tool of the Enemy.” We used torture to define the enemy and to separate the enemy from us. The use of torture by the enemy marked them. They were evil, intrinsically evil, because of their use of these techniques. Conversely, the victims were Americans or American allies. Torture killed or maimed, but it did not work. It was a sign of weakness. A good example of these themes and their development can be found in a series of World War II films, such as “13, rue Madeleine,” which was of course the address of the Gestapo in Paris during World War II.

This thematic approach held through the Cold War, when torture became more exotic and was presented as a still greater threat to the human spirit. Torture was an effort to crush the individual, to destroy the personality, to bend its victim to the will of the totalitarian state.

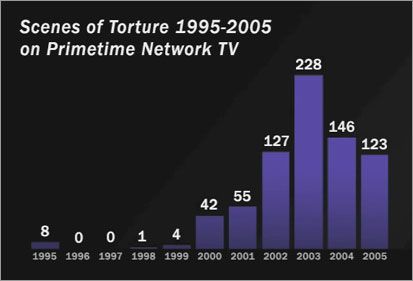

Still, torture scenes were relatively infrequent.

This graph shows the number of scenes appearing over a ten-year period 1995-2005. Notice the spike that occurs after 9/11.

Transformation from 2002

The entertainment industry latches on to the events of the day and tries to take a ride from them. That is the simple nature of things. So the reintroduction of torture as a theme in the broadcast world was to be expected. But something happened beginning in 2002 which was a bit surprising, and that was the fairly dramatic transformation of the way in which torture was addressed by Hollywood. I will be generalizing here, and there are exceptions to every statement, but I will focus on one single program: Fox’s “24,” which takes an easy first place in this process—if offers 67 torture scenes in the first five seasons—so it is responsible for a large part of the total number of incidents shown here.

Whereas before, torture was the “tool of the enemy,” now torture is the tool of Jack Bauer. Its use is a heroic act of defiance, often of petty bureaucratic limitations, or of conceited liberals whose personal conscience means more to them than the safety of their fellow citizens. While Bauer is presented as an ultimate heroic figure (and also a figure with some heroic flaws), those who challenge use of the rough stuff are naïve, and their presence and involvement in the national security process is threatening. We see a liberal who defends a Middle Eastern neighbor then under suspicion, and who winds up being killed because the neighbor is in fact a terrorist.

We’re looking at a Hollywood specialty: a “reality” show which is divorced from reality. It grossly simplifies necessarily complex facts, and it pares away critical factors which a responsible citizen should be thinking about. But more importantly, perhaps, it is a head-on attack on morality and ethics. The critics of torture are shallow figures, self-serving politicians—vain, arrogant, indifferent to the harm they are doing to society. But in fact the arguments against torture are profound and informed by centuries of human experience and religious doctrine. Torture has in the course of the last two hundred years emerged as an intrinsic evil in Christian teaching; the teaching of most churches – Protestant, Catholic, Evangelical – rejects the idea that a state can ever legitimately employ torture.

Key to “24’s” success is the ticking bomb scenario—indeed you hear it with all the introductions, breaks and trailers—the seconds ticking off. The myth of the ticking bomb is the core of the program. Torture always works. Torture always saves the day. Torture is the ultimate act of heroism, of defiance of pointy-headed liberal morality in favor of service to the greater good, to society.

We should start with a frank question: has “24” been created with an overtly political agenda, namely, to create a more receptive public audience for the Bush Administration’s torture policies? I think the answer to that question is now very clear. The answer is “yes.” In “Whatever It Takes,” Jane Mayer has waded through the sheaf of contacts between the show’s producer, Joel Surnow, and Vice President Cheney and figures right around him. There is little ambiguity about this point, namely, if the torture system introduced after 9/11 can be traced back to a single person, it is Vice President Cheney. He pushed relentlessly for use of the tools of the “dark side,” and he ruthlessly took out everyone who stood in his way. He also worked feverishly to disguise or cloak his intimate involvement in the entire process. I take it as a given that Surnow is working to develop public attitudes which are more accepting of torture and to overturn centuries-old prejudices against torture. He is a torture-enabler.

The key to achieving this objective consists of two steps. The first is to reduce the issue to something simple: Does torture work? If it does, why should we ever rule it out? Any other question will be dismissed as a moralizing quibble, not something that virile men would worry about. I call this the “Rambo approach.”

The Missing Elements

We should all be focused on the gap between reality and the world of “24.” Here are the major points I would make:

• The irreality of the ticking-bomb. For one thing the fact that the ticking-bomb scenario upon which they build has never occurred in the entirety of human history. It’s a malicious fiction. The facts posited will simply never occur. But beyond this, while we are asked to keep our eye on the ticking-bomb scenario, it has nothing to do with the cases in which highly coercive techniques are actually used—look at the testimony of Steven Bradbury before the Judiciary Committee. He cited three instances in which waterboarding, an iconic torture technique, was used. None of them involved the ticking-bomb or anything like it.

• The reliability of torture. The Intelligence Science Board looked at the question extensively and came to clear conclusions in December 2006. Torture does not work, they said. Indeed, one passage of their report was clearly a swipe at “24” which they said rested on a series of absurd premises. The belief that a person, once tortured, speaks the truth is ancient and very false. Torture, when applied, seems very likely to produce false intelligence upon which we rely to our own detriment. Ask Colin Powell. He delivered a key presentation to the Security Council in which he made the case for war against Iraq. The keystone of Powell’s presentation turned on evidence taken from a man named al-Libi who was tortured and said that Iraq was busily at work on an WMD program. This information, of course, was totally wrong. Al-Libi fabricated it because he knew this is just what the interrogators wanted to hear, and by saying it, they would stop torturing. It was a perfect demonstration of the tendency of torture to contaminate the intelligence gathering process with bogus data.

• Containment. Can torture be introduced and used only in a highly limited set of cases, usually against cold-hearted terrorists, the worst of the worst? Is there not instead an inevitable rush to the bottom that results in any limitations being disregarded? The corrosive effects of culture on a society altogether.

• For another, the nation’s reputation in the world. Generations of Americans have fought and sacrificed to build a system of alliances around the world that provide our security bulwark. What has happened to those alliances? In country after country—including many of the nations which have historically been our tightest allies–our government’s approval level is, as now in Turkey, within the margin of error. That’s right. The percentage approving may actually be zero. In nation after nation and even among our own allies, we are outstripped by the world’s last Stalinist power, China. This is a very heavy price, and most of it has to do with torture policy. So torture policy erodes confidence of our community of allies in us, makes them hesitant to share intelligence, and to support us in counterterrorism and other operations. I have studied in some detail the consequences of U.S. torture policies for operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, where it is clear that allies are dropping out and loosing enthusiasm for supporting operations, and torture policies provide the single most important motivator in this process.

• Damage to military morale and discipline. George Washington was famous for his opposition to torture. He came to his views not for idealistic but for practical reasons. During the French and Indian Wars he observed brutal tactics being used in the wilderness, and he saw that the soldiers who used them were bad soldiers—disorderly, poorly disciplined, impossible to control. He concluded that torture destroyed morale and discipline. And that continues to be the accepted wisdom of the military today, and the force behind the historically unprecedented opposition of military leaders to Bush Administration policy that we saw in the winter of 2006-07. The dean of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, BG Patrick Finnegan, visited the writers of “24” to present a complaint. This program was actually corrupting military intelligence and discipline. Soldiers in the field reach to the techniques employed by Jack Bauer—if he can use them, why can’t we?

• And the weightiest link in this chain tied around our national neck should be considered last. As my friend Mark Danner writes, if you assembled a team of Madison Avenue’s most brilliant thinkers in a room and asked them to concoct a recruitment plan for al Qaeda and its allies, we’d never come anywhere close to the one that the Bush Administration delivered up to them with the torture program. It’s the major reason why today, six years after the start of the war on terror, the National Intelligence Estimate tells us that al Qaeda is back up or has exceeded the strength it had on 9/11, and the Taliban has also been able to regroup and recharge, destabilizing a friendly government in Afghanistan.

The current season of “24” set to begin shortly features a senate investigation looking into Jack Bauer. A Senator is out after our hero, but he defends himself brilliantly and in the end, the senate committee, we are told, sees the light and comes to understand Bauer’s heroic qualities, including his willingness to use torture.

America today is witnessing something like the experience of France during the Algerian conflict. Albert Camus noted and developed this carefully over a period of many years in his Chroniques algériennes. He saw a polarized society in France, between conservatives, traditional liberals and the Left. But there was no constituency to oppose torture. The Right embraced the cause of the colonials, and justified their reach to harsh tactics. First this was justified by arguments that the barbarity of the people justified treating them in ways that in Europe could not be countenanced. (This was an echo of arguments that Tocqueville examined a century earlier in the first Algerian war). But this wasn’t a satisfying basis for a society built on liberty, equality and fraternity. So the second justification was more appealing, and it was the ticking-bomb. Camus notes that the Left also could not muster arguments against torture. It was then still in the embrace of Stalinism, which had taken with relish to the same techniques. Who remained to make the moral and social argument? Camus did. He puts it powerfully near the conclusion of that book.

Though it may be true that, at least in history, values, be they of a nation or of humanity as a whole, do not survive unless we fight for them, neither combat (nor force) can alone suffice to justify them. Rather it must be the other way: the fight must be justified and guided by those values. We must fight for the truth and we must take care not to kill it with the very weapons we use in its defense; it is at this doubled price that we must pay in order that our words assume once more their proper power.

This is the fundamental dilemma that “24” dodges. What are the values for which Jack Bauer is fighting? Is he not abdicating them by his conduct? I am not advocating censoring of “24.” But it is critical that “24” begin to present this vitally complex and important social issue in a mature, responsible way. Right now, it is multiplying our problems.

Remarks delivered at the University of Chicago School of Law, Chicago, Illinois on March 1, 2008.