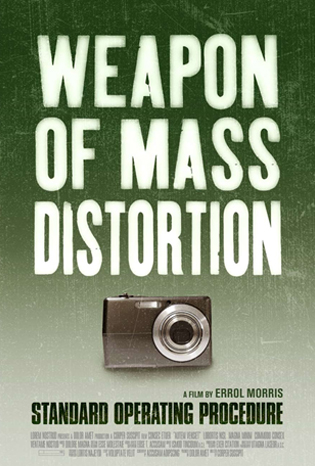

Starting with Gates of Heaven in 1978, filmmaker Errol Morris has directed a series of genre-defining documentaries, among them The Thin Blue Line, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control, and The Fog of War. (Morris also does a fair amount of writing, as seen on the “Archive” page of his website.) Harper’s contributor W.J.T. Mitchell, whose article “The Fog of Abu Ghraib: Errol Morris and the ‘bad apples'” appears in the May issue, interviewed Morris about Standard Operating Procedure (Sony Pictures Classics), a documentary about the abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq–more specifically about the photographs of those abuses–will be released tomorrow, April 25.

What questions were left unanswered for you after you had completed Standard Operating Procedure? Who else would you like to interview? Have you tried to interview any of the Iraqis who were in Abu Ghraib?

Endless questions. I am still interviewing people. Here is one question currently on my mind. Why did Mark Swanner, the CIA agent partially responsible for al-Jamadi’s death, skate away without punishment?

What mysteries remain?

Abu Ghraib was an immense prison. At the end of 2003 there were by some accounts 10,000 prisoners there. Imagine a city of 10,000 people, and then imagine what mysteries they might pose. In January 2004, Colonel Thomas Pappas, under the guise of an amnesty, ordered the destruction of huge amounts of evidence. Hard drives were erased, documents destroyed, but in all likelihood there are still records of interrogations, phone calls between the Joint Interrogation and Debriefing Center, the intelligence hub of Abu Ghraib, and the Department of Defense. I would like to see them.

How to solve these mysteries?

Real-life mysteries are only solved one way: by collecting evidence–interviews, documents, photographs et al.–and then thinking about it. By investigating. There is no great mystery to solving mysteries.

What would you ask Charles Graner if you could question him?

I would sit him down for one of my brief interviews. My interview with Janis Karpinski was seventeen hours long. I would give Chuck Graner at least that much time.

Who else would you interview?

Ivan Frederick. He got out of prison too late for me to interview him for SOP. And many of the people who turned me down. All of the soldiers present the morning of al-Jamadi’s death. Many of the Titan translators and CACI interrogators. Captain Wood, Major Price, Colonel Pappas. The list is endless.

Is there a difference between your use of what I would call “forensic” reenactments in The Thin Blue Line and the kinds of reenactment you created for SOP?

Yes and no. I have used reenactments in all of my films. I hear a line in an interview and it suggests an image. In The Fog of War, McNamara discusses his work at Ford on automobile safety. Padded dashboards, collapsible steering wheels, seat belts, etc. He suddenly, unexpectedly tells a story about dropping skulls–padded and unpadded–down a stairwell at Cornell. I thought to myself, what an image! McNamara even when he’s trying to save lives is dropping stuff from the sky. O.K. I “illustrated” the line. It is a way of directing or re-directing attention to a specific thought or idea. In Standard Operating Procedure, I do something similar, but the “illustrations” direct attention to moral quandaries, disturbing details–and many of them involve the photographs. Tony Diaz, an MP, discovers that al-Jamadi is dead. Diaz didn’t kill him, but he helped suspend al-Jamadi in a Palestinian hanging, a stress position, not unlike a crucifixion. He describes how a drop of blood fell on his uniform. He tells him himself that he is not involved, but he knows he is involved. I illustrated the falling drop of blood. It takes us into Diaz’s moral quandary–I am not involved but I am involved–and our own.

Were you aiming to re-enact the subjectivity of the soldiers?

Yes. Absolutely. The hope is that it takes us inside their experience.

You have written at length about the strange effects that photographs have on viewers, persuading them of the self-evident meaning of what they see–while, at the same time, they are liable to attract all kind of misconceptions and ungrounded beliefs. What lessons do you draw about the changed conditions of photography in the digital age from your experience with the Abu Ghraib images?

The problem is with photography–both still and moving images. Photographs are ripped out of the world and stripped of context regardless of whether they are “chemical” or “digital” images. Of course, digital photography has changed how photographs are viewed and how they are distributed. Now, photographs are not printed on paper, they are displayed on screens. And they are not sent in the mail or over telephone and telegraph-wires, they are sent as digital attachments in emails or posted on FTP sites. A photograph can be sent to 100,000 different places with one click. Photoshop, however, did not inaugurate an era of photographic fabrication, manipulation, and falsification–that started with photography itself. Photoshop points out something we should have known all along–that we are easily fooled by photographs, even photographs that haven’t been manipulated at all.

There are two characters in SOP that play something analogous to your own role as detective and forensic analyst: Sabrina Harman, who claims she took the photographs to expose the scandal, and Brent Pack, the military investigator who established the time-line of their production. Do you feel a special connection or affinity with these people? Are they “on the side” of your film in the debate over the meaning of Abu Ghraib?

I like both of them. Brent Pack, for his candor, which I find entirely admirable. Sabrina, for her curiosity and for her compassion. I talked to Qaissi, the prisoner known as Clawman. Sabrina had taken photographs of him the same night she took the photographs of the hooded man on the box with wires and the photographs of al-Jamadi’s corpse. Qaissi remembers Sabrina fondly. He said to me, “She was a good one.”

You have established a distinctive style as a documentary filmmaker, linking it to fictional genres like film noir and horror. Can you define the basic rules and methods that govern your style? Do you have a list of dos and don’ts? A theory of documentary?

Well, I have a theory of art: set up an arbitrary set of rules and then follow them slavishly. Documentary can be anything–that’s what I love about it. However, there has to be one underlying intention, one underlying goal–to find out something about reality.

What is your next project? And over the longer haul, what other projects can you imagine taking on?

Next up? I would like to continue my TV series “First Person.” I have a film–part drama, part documentary–with a catchy title: The End of Everything. It has Margaret Mitchell, Laura Bush, one active volcano, and 100,000 albatross eggs. I am hoping that Cate Blanchett can play both Margaret Mitchell and Laura Bush. Many people can say “I have an albatross around my neck.” But how many people can say, “I have an albatross movie around my neck”? I look forward to it.