Meaningful art—however long it might take—always reaches its audience. Writers or painters who work in obscurity and struggle to get an agent or gallery to give them a shot will, if their work warrants attention, eventually get it. That the attention may be too little or come too late, that the artist in the interim will have a fittingly miserable time being overlooked and unsupported–these sad facts are common enough, as anyone who has read, say, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, understands.

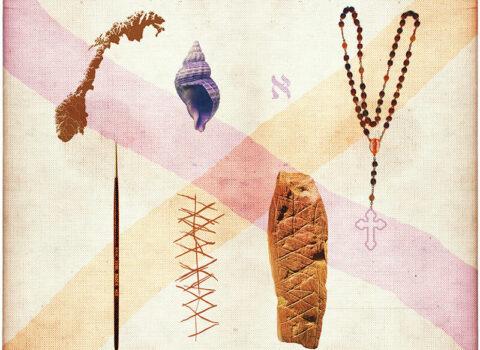

This week on Sentences, I’ve featured the work of gifted writer Lamed Shapiro (1878–1948), of whom I’d not heard until last week. And yet the collection published by Yale University Press in 2007, Shapiro’s The Cross and Other Stories, is superior in every conceivable measure to any gathering of short stories I read in the past year.

This is not to say that we’ve been suffering from a lack of good short fiction. But these are masterpieces of the form. Shapiro’s art is an instance of a writer having found both his subject and the best means of serving it. He writes of the struggles of Jews living in the Europe of pogroms and of the struggle of the Jews who survived, and who tried to live decently in the wake of the violence, often failing at that task. No one, in my experience as a reader, has treated their particular rage–the rage of a people that others have attempted to expunge–so purely as Shapiro. Such a subject is beyond questioning as serious matter for fiction, and Shapiro skirts the easy pits of the sensational and the sentimental in his telling. He writes with the apparent understatement of a spoken style, but that style is tuned with a precision that approaches, in its insinuating music, song.

That I and, perhaps, many of you, had not heard of Shapiro’s The Cross and Other Jewish Stories is—at least from a practical standpoint—not surprising. Although published by Yale University Press, The Cross was not reviewed in Publisher’s Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, Library Journal, or Booklist, much less in any newspaper or magazine that did not have, in its name, either the word “Jewish” or “Jerusalem”. This is a misfortune, and one which can be addressed, if not by editors, readers. As such, for this week’s Weekend Read, I am happy to present Shapiro’s “The Cross.” It was the best story I’d read this year, until I read the remainder of those in the collection it begins. With thanks to Yale University Press for permission to reprint it here.

The Cross

1

His appearance:

A gigantic figure, big-boned but not fat, thin really. Sunburned, with sharp cheekbones and dark eyes. The hair on his head was almost entirely gray, but oddly young, thick, lushly grown, and slightly curly. A child’s smile on his lips and an old man’s tiny wrinkles around the eyes.

And then: on his wide forehead a sharply etched brown cross. It was a badly healed wound–two slashes of a knife, one across the other.

We met on the roof of a train car which was crossing through one of America’s eastern states. And as we were both “tramping” cross-country, we agreed to do it together until we got tired of each other. I knew he was a Russian Jew just like me, and I didn’t ask anything else. People like us live the kind of life where you don’t need passports.

That summer we saw practically the entire United States. By day we used to travel on foot, cutting through woods, and bathing in the rivers we found along the way. The farmers provided food. That is, some of them gave, and we stole from the rest–chickens, geese, ducks. Afterwards we’d roast them over a fire somewhere in the woods or on the “prairie.” And there were also days when, with no other choice, we made do with forest berries.

Sleep came whenever night fell: in the open fields or under a tree somewhere in the woods. Sometimes on dark nights we “hopped a train.” That is, we went onto the roof of a car and hitched a little ride. The train flew like an arrow. A sharp wind hit us in the face, carrying the smoke of the locomotive in bits of cloud, dotted with many sparks. The prairie ran and circled around us, and breathed deep, and spoke quickly and quietly, with a multitude of sounds in a multitude of tongues. Distant planets sparkled over us and thoughts entered and swum about our heads, such strange thoughts, wild and open as the voices of the prairie: they seemed each unconnected to the next, they seemed knotted and linked and ringed together. And at the same time, beneath us, in the cars, people sat and reclined, many people, whose path was set and whose thoughts were confined; they knew from whence they came and whither they went, and they told of it to each other and yawned while they would do it, and they would slumber, not knowing that above, atop their heads, there were two free birds resting a while on their way. From where? Whither? At dawn we would jump down onto the ground and go to snatch a chicken or catch fish with makeshift poles.

On one of the last days in August I was lying naked on the sand on the bank of a deep and narrow river and was drying myself in the sun. My friend was still in the river and was making such a ruckus that it seemed like a whole gang of kids were bathing there. Afterwards he got out onto the bank, fresh and gleaming from head to toe. The brown cross on his forehead stood out particularly distinctly. We lay on the sand next to one another for a little while, lay there and kept quiet. I wanted and didn’t want to ask him what sort of mark that was on his forehead. Finally, I posed my question.

He raised his head from the sand and gave me a curious look with a hint of mockery.

–You won’t get scared?

I hadn’t been shocked by anything for years.

–Tell me, I said.

2

My father died when I was a couple of months old. From what I heard about him, I understand that he was a “somebody.” A man from another world. I carry around his picture–one entirely made up by yours truly–in my imagination, because, like I said, he was a somebody. Anyway, the story I’m going to tell isn’t about him.

My mother was a thin Jewish woman, tall, big-boned, dry and gloomy. She had a little store. She fed me, paid my tuition, and hit me plenty, because I didn’t grow up the way she wanted.

What was it she wanted? I’m not completely clear on that. I think she probably wasn’t clear herself. She always used to fight with my father, but when he died, she, a thirty-two-year-old woman, used to shake her head at any suggested matches:

–No, after him it’s not right, I don’t need anybody, and how can I take a stepfather for my child?

She never remarried. So I, naturally, had to be like my father, only without his faults. He never really belonged in this world of ours, he was, she used to say, “too passionate.” And so the story went. She used to beat me brutally, without mercy. Once–I was about twelve then– she started to beat me with an iron pole that she used to close the shutters of her shop from the inside. I got furious and hit her back. She stood there pale, with big eyes, looking at me. From then on she didn’t hit me any more.

The atmosphere between us in the house got even colder and tenser than before. About half a year later I went out “into the world.”

Describing everything would take too long and it wouldn’t be interesting either. Let me get to the main point. Fifteen years later, I was living in a big city in the south of Russia. I was a medical student and lived off tutoring. I took my mother in, but she was only living with me, she was taking care of herself: she bought and sold used clothing at the market. She didn’t have anything to be ashamed of about the living she made, but she looked down on all the other old clothes dealers: who is she? Who are they?

She was as cold to me as before, at least on the outside, and I was just as cold to her. It even seemed to me that I hated her a little.

But if you went a bit deeper, she didn’t bother me as much. I lived in an entirely different world.

3

It was a minor matter: we wanted to remake the world. First Russia, then the world. In the meantime we focused on Russia.

At that time the whole country was feverish with excitement. Larger and larger groups of people were being pulled into the stream, and above their heads exploded, more and more often, like a rocket, the hot, red, fire of individual heroic acts. Well-established heads, high and low, were falling one after another, and the old order was responding, and responding well, among other ways by pogroms against the Jews. The pogroms made no particular impression on me: we had a word for them then, “counter-revolution.” It explained everything perfectly. Yes, I had never at the time actually lived through a pogrom: our city was still waiting for its turn.

I was a representative in the local committee of one of the parties. This wasn’t enough for me. A thought, sharp as a knife, had slowly but surely cut its way into the depths of my brain. What was it? I wasn’t clear exactly and in the meantime I didn’t want to know. I just had the feeling that my muscles were becoming stiffer, tenser, and I once found that I absentmindedly had used my bare hands to shatter the back of a chair in one of the houses where I was giving lessons. I was left standing there completely confused. Another time my student asked me, wonderingly, “Who’s Mina . . . ?”–and I understood that, lost in thought, I had said the name “Mina” out loud. And I also understood, that though my thoughts were about one thing and “Mina” was seemingly just a girl’s name, that thought was always connected to Mina’s picture, to the sounds that come together with the name “Mina.” That particular feeling of significance and importance that was always in the air when Mina was present.

Besides me, the committee consisted of four men and one woman. I don’t know what color eyes the men had, but Mina’s were blue, bright blue, and at certain moments they grew dark, black and finally deep, pitch black, like a pit. Black hair, a regular, graceful figure, and something slow and serious in her movements.

At our meetings she didn’t argue much. She used to make a suggestion, or give her opinion about a situation in two or three pithy phrases, and then sit quiet and attentive with her shortsighted eyes squinting slightly. And very often it turned out that, after a long time, once we had heatedly debated and gone over the question and had cleared up all the misunderstandings, we, a little amazed, came to the same conclusion that had already been formulated in Mina’s two or three pithy sentences.

She was a daughter of a senior Russian official. That was all we knew about her. At the door of our underground cell each of us would throw away our personal lives, like an overcoat in the foyer.

4

In our city the cloud of a pogrom was quickly approaching the Jews. Strange sounds swirled around the city, sharp and quiet sounds, like the hissing of a snake. People went around with their ears perked up, with quick, sideways looks, and gestured with their noses as if detecting a suspicious odor. But quietly and with cunning.

One hot afternoon we gathered together for an additional meeting at Mina’s apartment, which also served as our underground cell’s headquarters. The meeting didn’t last long: short deliberations, no debates, and a decision to organize in self-defense as quickly as possible. In the course of the meeting I noticed Mina glancing at me occasionally. When the members of the committee began to leave, she gave me a sign that I should stay behind.

I remained there with my hat on my head, leaning my back and both hands against the table, while Mina, with her head bent and her hair spreading over her breast, paced back and forth across the room. We were quiet. After a while, she raised her head, stopped, and looked straight at me. She was pale, very pale, and her eyes were dark and black, as only Mina’s eyes could be.

I felt cold. In a flash, as if illuminated by a strong and sudden outbreak of fire, my thoughts became clear to me: to become one of the “rockets” who light the way of the revolution, and who pay the price doing it.

And Mina was the first to understand! She saw it on my face, before it was even clear to me. Why . . . ?

–Have you decided? She asked after a while, with a voice half hushed.

–Decided. I answered slowly and firmly, feeling like the decision was being made that very second.

She looked at me for a while, and started pacing around the room again. After a few minutes she became as serious and still as always.

–Anyway, we’ll still see one another, she said and gave me her hand.

Going home to mother, I felt that every bone in my body was singing. And I thought about the strange fate of a person, whose life’s short path takes him between one woman he practically hates to another that he’s beginning to love.

Before I opened the door of my apartment, I took a look at the city. The sun was just going down, and a light, delicate veil, spun of gold and happiness, lay in soft folds on the streets and the houses. Our city was a beautiful city.

5

We were too late. That very same night the pogrom broke out. Suddenly, like an explosion from a buried mine, and right in the area where I lived.

The first screams were mixed up with the haze of the dream I was having. Then I suddenly figured it out, got out of bed, lit a fire, and started quickly getting dressed. At that moment my mother sat up in bed and gave me a funny look.

I felt creepy. It was like she was looking at me coldly and ironically, as if the pogrom were aimed at me and not her. I stood there motionless for a minute, half-dressed. I looked at her, confused. And at that very moment the house trembled, as if it were in the arms of a storm.

The windows exploded with a crash, one door was smashed after another, and a gang of pogromists tore into us along with a foaming wave of broken screams and cries from the street.

I’m a strong man. But until that night I had never had to hit someone in anger. Until that night I didn’t know the meaning of true rage which intoxicates, like powerful wine; of anger, that instantly boils your blood, that fires up your whole body, that hits you in the head and pervades all your thoughts. When the pogromists, a varied group, young, old, some with “homemade” weapons and some without weapons at all, attacked me, at first I coldly defended myself. But I was dazed at the same time, as if I didn’t exactly understand what it was they wanted from me. Suddenly, after some little thing–I think that someone smashed my writing utensils on the ground–a white heat took control of my whole body, my head started to get dizzy and my hand raised up of its own accord. Across from me there was this short little goy, not very big at all, with a thin, pale face, a stiff yellow mustache and small, pointy eyes full of cold-blooded murder. I remember how I slammed my fist into that face, and couldn’t hold back a strange bellow, like a wild ox. After that everything spun around me and in me, spun around fast and hot, and I was having a great time.

I don’t know how long it lasted. My anger and my enjoyment grew at the same rate that my strength met resistance and overcame it. At the same time, a kind of chirpy, unyielding voice reached me from somewhere far away, like the buzzing of a mosquito, along with disjointed words in Russian: “Don’t have to . . . don’t have to . . . tie him up! Tie him up!” The resistance started to grow quickly, more quickly than my strength, from all sides, from above, from below, until it suddenly froze around my entire body, like a stone skin. The joy disappeared, and the anger, the pure hellish anger, scorched my breast and choked my throat. Little by little it cooled, froze and then settled in my heart, like a heavy shard of ice. I came to my senses.

I was lying on the ground tied up, almost entirely wrapped up in rope, hurt, bloody, and the little goy with the pointy eyes was dancing around right near me, but with a really bloody and rearranged face. I also noticed blood on the faces of the other guys standing around me.

They picked me up off the ground like a full gunnysack, and tied me to the footboard of my mother’s bed.

My mother! Only now I remembered about her. She had jumped off the bed, apparently to help me, but now someone had dragged her back onto the bed where I was tied up.

I almost didn’t recognize her in her shift. Wide, thin bones. Wildly disheveled gray hair and sparkling eyes. Her teeth tightly clamped together and silent. They had thrown her into the bed, across from me.

6

Just imagine:

What’s a hair, one single gray hair, pulled out of a head? Nothing, nothing at all. And two hairs? And a clump, ripped out all at once? And many clumps of long, gray hair? Pssh! Absolutely nothing.

Sure, when you break bones they crack. But if you break little sticks, dry wood, and–who knows what else?–they crack too; that’s a “natural occurrence.”

Just imagine:

What are two old, shriveled breasts? Flesh. Matter. They consist of certain “elements”–just go ask a chemist. Even when they’re your mother’s breasts. Two modest breasts that nursed you, and that you’ve never, not even once, seen uncovered since you were a little kid. Even if they’re torn into tiny pieces by filthy fingers right in front of your eyes?

Tell me, I ask you:

What does nature, the world, know about filth and shame? There’s no such thing as filth or shame in nature.

Yes, it’s true: never, never was a human body, the glorious body of man and woman, so degraded and debased! But–why should I care? Because–you should know: there’s no such thing as filth and shame in nature.

A year or two pass by, and ten, and a hundred, and two hundred. How is this possible? How is it possible that I can live so long? Can a man live so long?

Mama: scream, oh scream! Damn you! What do you think, it’s one of those times when you used to hit me so wickedly and you kept so quiet! Just one scream, just a groan! Oh, God! . . .

Years and years . . .

Do you see that bloody face over there? That’s the first human face I ever saw in my life. A harsh, gloomy face, but also the first I ever saw in my life. The woman with that face used to beat me, and I hated her. And I still hate her even now, and even more than before, and my hate sticks in my throat and chokes me. Because why then, if not out of hate, do I stare with such intensity at how the face changes from minute to minute? Why don’t I close my eyes? Why do they bulge out of my head, with such pain and such burning curiosity? Good, dear people: tear out my eyes. Why should it trouble you at all? One slice with a knife, they’ll fall right out–these two watery bubbles, these–these–two cursed watery bubbles, which, I swear, I don’t need any more. You laugh! You’re merry people, very merry, but tear them out, why should it trouble you at all?

Years and years.

7

The little goy said:

–The old bitch still won’t scream. Just let me at her.

A little while passed, and then I heard a sound. It was a groan, a cry, a scream all at once, and there were words in the scream, and though the voice was hoarse and wildly changed, the words rang in my ears loud and clear, like slow, distinct chimes of a bell:

–Oh, my son!

For the first time in her life.

Sweat poured like rain off my forehead and filled my eyes. I gave a jerk with all my might, and the rope cut deeper into my body. God was merciful for the moment: my head spun, and I lost consciousness. But I did manage to hear the laughter all around me.

Later I came to for a minute, and the little goy was talking again:

–Enough. Let her kick the bucket little by little right before his eyes. And I’m gonna cross him up, to save his kike soul from hell.

I felt two deep cuts on my forehead, one across the other, and heard laughter again. A small warm stream ran down my forehead, over my nose, and into my mouth.

I lost consciousness for a second time.

8

Absolute darkness. Absolute silence. Not a single external impression, and no firm internal point. Only everywhere an uneasiness, a heavy uneasiness and a huge effort to find some sort of point.

A single word wandered about in this world of darkness and void, a tiny word: “What?” And three times: “What?” “What?” “What?” And twenty times “What?” The word grows and it spreads and it increases and out of this it becomes: “What is here? What is around? What is me and what is outside of me?” Suddenly a sharp brilliance and a strong pain are in my head. Three words stick in my brain like a thin, long needle that is stuck in one ear and going out the other: “Oh, my son!”

In a moment I regain consciousness.

Night. The lamp has gone out, or they have extinguished it before leaving. I stand tied to the bed, and I feel, on my forehead, a wound burning, burning sharp and making me forget all the other wounds. From the city different sounds reach the room: the city screams in the middle of the night, muted screams with occasional sharp outbreaks like a distant fire. Not far from me, on the bed, something quivers in the darkness.

–Mama!

Silence.

–Mama!

No answer. My voice doesn’t make it there, in the world of torment, where her harsh, rough spirit is flying around. “Oh, my son!” she called me. Yes, her son, since every drop of blood which she has now spilled flows into my veins through unknown paths and lights a hellish fire there. “Oh, my son!” A heavy hammer is raised slowly and unceasingly up and down. Every time it lands on my head whole worlds collapse in ruins.

9

–What’s that on your forehead?

–That’s something to save my soul from the torments of Hell, I answer.

They shake their heads and begin to walk away. I become uneasy.

–Wait, I say. I’ll explain it to you.

They shake their heads and disappear.

“I am the Lord your God, who has taken you out of the Land of Egypt!”

“Thou shalt have no other gods before me!”

“I am a zealous and vengeful God–and I demand of you: be something!”

The breath of the storm spreads out over the shaken camp. The servile bodies tremble, as if under the lash, but the dark, thin faces and the dark feverish eyes are lit with the red fire that wreathes the mountaintop.

“Oh, my son!” she said. In those very words: “Oh, my son!”

Daylight.

My head is empty and swollen like a barrel. I had to get away from there. Yes, get away, but–ah, the rope. I had to find a way. There has to be some kind of way. Some kind, some kind of way.

I struggle to collect my thoughts as much as I can.

There’s an iron nail. In the footboard I’m tied to, a wide-headed nail is pounded in and half-bent. What’s a nail doing here? That’s not important. But with a nail you can–what can you do with a nail?

I tossed and turned for a long time until I had managed to snag one end of the rope onto the nail. Then I started rubbing the rope over the sharp iron head.

Hours passed. I became confused and hardly knew what I was doing, but I have, apparently, continued my work with the exactness and the stubbornness of a machine. Then the moment came, and the rope gave a little. A little more effort, a little more–and at my feet lay tattered, frayed rope; at my feet there lay the shattered shards of gods.

10

I bent over the bed. There was definitely something there. It was feverish and had no resemblance to a human being, but the groans had already become so quiet, my ear could hardly catch them. I spoke quietly: “Mama . . .” My breath reached the wound that was formerly a face, and I said once more: “Mama!”

Movement took place over the wound, and something opened. I looked at it closely. This had been an eye. An eye–the other had leaked out. The eye was soaked with blood, but despite that it sparkled, like a glowing coal.

Did it recognize me? I don’t know. It seemed to me it did, and that it looked at me with a question and a harsh demand. “Yes, yes, it’s going to be fine!” I said loudly and seriously, not knowing for certain what I was talking about.

Afterwards I looked around the room. A table leg lay among the other pieces of smashed furniture. It was round, thick, and well-shaped. It would do.

I raised the table leg and with all my might I brought it down on the glowing eye. The bloodied something gave a single twitch and then lay there like a stone. The glowing eye was no more.

A short sigh and a kind of strange, quickly stifled roar reached my ear. But this was against my will, I assure you. The voice was so strange, that I wasn’t sure whether or not it was mine.

When I went out onto the street the sun was about to set. That old sun, that had spun its gold here a thousand years ago. Who was it that said that a thousand years was more than a day? I was a thousand years old.

11

And so began the darkest day of my life.

The city had survived a sort of fever. Arson, murder, bloody beatings and shooting in the streets. A self-defense unit had indeed been organized while already under the fire of the pogrom.

What did I do then? I don’t know. First I found myself among the ranks of the self-defense corps, and then in the masses of the pogrom-ists. I felt like a leaf carried along by a storm. On my forehead, the cross burned. In my ears, “Oh, my son!” rang.

If I’m not mistaken, I once encountered my goy–the goy who, by all accounts, belonged to me alone. I had the feeling that if I wanted to, I could take him and put him right in my pocket. He grew pale, and, apparently, couldn’t move. I didn’t take him, though. He awakened nothing in me. I just gave him a friendly smack across the shoulders and winked at him merrily with one eye. I didn’t notice whether this inspired more courage in him.

A second scene has remained in my memory.

An old Jew is running across the street, and after him a young goy about sixteen, an axe in hand. The goy catches up to the old man and with one blow splits his head open. When the old man falls, the goy presses down on his split head with his boot.

At that moment a young Jewish man runs over with a revolver in his hand. A pale young man, a thin face. Glasses.

They run, and I follow. The young Jew shoots and misses. The goy abandons the wide open street and ducks into a courtyard. I trip on something and fall.

When I got to the courtyard, the goy was standing in a corner with his back leaning against a fence. His almost childlike face had turned green, his gray eyes were huge and round, and his fine teeth were chattering quickly.

The young Jew stood right up close to him with the revolver in his raised hand, but his face was even paler than before. He looked at the wild fear of the young flesh and blood, looked for a moment, and then he placed the revolver to his own head and fired.

The last remnant of sanity vanished from the goy’s eyes. He sat down next to the body that was twitching near his feet, stood up again and with a mad cry jumped over the corpse and ran out of the courtyard.

A loud laugh tore out of me. My foot raised of its own accord and gave a kick to the bloodied corpse that was writhing on the ground, like a trampled worm.

12

This went on for days and nights. I don’t know how many. One evening I stood at a door and knocked on it in a certain way. It was a sign that one of us was coming. What sort of signal was that? What purpose did it serve and how did I come to know it? I never asked these questions, the same way you don’t ask those kind of questions in a dream. The door opened and I saw Mina.

Lightning flared in my brain, and for a moment I was overwhelmed by terror. I understood where I was and what I was going to do. And at that moment I grew calm.

She didn’t recognize me right away, and then she gave a little shudder. She grabbed me by the hand and pulled me into the room. I let her sit me down on a chair.

She looked at my head and at my forehead where the cross burned, and was silent. Afterwards, she said with a muted voice:

–Tell me.

I told her. I told everything gladly, slowly. In detail. The agonies of my mother and the shameful details. On her face the colors kept changing: red, white, green and yellow. When I finished, I bowed to her with a pleasant smile. She hardly noticed and buried her face in both her hands. Afterwards she uncovered her face, which was stained with real tears. I swear to you: wet, soft, and so warm. She got down on her knees in front of me and took my hand. My smile grew wider. This time she saw it, and quickly got up from the ground, and started to go back and forth across the room, casting nervous glances in my direction. I just sat there and smiled, as it seemed to me, very pleasantly.

Finally she decided to try something which she, apparently, supposed was very clever. She sat down once more on the chair across from me and asked quietly:

–And your decision?

My decision? What decision? Wait a minute. Yes, years ago, many years ago, I had made some sort of decision, a very important decision, but–about what? Suddenly I remembered.

I laughed right in her face. Then I immediately grew serious and looked her right in the eyes. She turned white, like linen, and jumped out of her chair. Slowly and calmly I also stood up.

I raped her.

She defended herself, like my mother. But what good were her powers against the man with the cross on his head? Flaming redness and a corpse’s paleness played frighteningly across her face. She didn’t scream. She bit her lower lip, chewed it and swallowed the blood. And I did my work. With all of the attendant degradations. It lasted a long time.

Afterwards I strangled her. I did it fast and thunderously. I sank my fingers, my long, bony fingers, into her white throat. She turned red, blue, and then black. The end came quickly.

I threw myself down onto a chair and immediately fell asleep, as if I had sunk into deep water. Dreamless.

13

When I woke up I noticed that the candle on the table had hardly shrunk at all. I had probably slept no more than fifteen minutes. But I was refreshed, lively and calm. The exclamation: “Oh, my son!” hasn’t left me to this very day, but it has become softer, more maternal. My mother’s soul had found its peace.

Our underground cell was arranged comfortably, almost elegantly, so as to eliminate any suspicion. I went into the bathroom and washed my face and my hands thoroughly. The mirror showed me that my hair had turned gray. I finally saw the cross that I had only felt this whole time. The wound didn’t hurt any more, it only stung a little.

At first, I wanted to take a knife, cut a slice out of my forehead and erase the cross. Afterwards I reconsidered. It should stay. “They shall be frontlets between your eyes . . . ” Ha! Were these the sort of “frontlets” our dear, old God had meant?

14

I didn’t owe anything to anyone and I didn’t want to pay for anything.

That very same night I left our city. A few days later I crossed the German border and set sail for America.

The sea greeted me with endless vastness, with raw winds, and sharp, salty breath. It spoke to me of wondrous things, both out loud and silently. I listened to it with joy and with astonishment. I will not tell you in words what it related to me.

Almost immediately after my arrival in America I began to wander across the land. The prairie began to explain in its own language what the sea had meant with its speech. Ah, the prairie! Her nights, her days!

It has been three years that I have wandered. And I, newborn child, feel, that I have become strong enough. Soon I shall return to civilization.

And then–

I looked over in his direction, but he didn’t say anything else. He had, apparently, forgotten all about me.

And I, a man who hadn’t been shocked by anything for years, thought:

There will come a generation of men of iron. And they will build that which we have let lie in ruins.

(1909) Translated by Jeremy Dauber. “The Cross” is excerpted from The Cross and Other Jewish Stories by Lamed Shapiro, Yale University Press, 2007.