Um Mitternacht

Hab’ ich gewacht

Und aufgeblickt zum Himmel;

Kein Stern vom Sterngewimmel

Hat mir gelacht

Um Mitternacht.

Um Mitternacht

Hab’ ich gedacht

Hinaus in dunkle Schranken;

Es hat kein Lichtgedanken

Mir Trost gebracht

Um Mitternacht.

Um Mitternacht

Nahm ich in Acht

Die Schläge meines Herzens;

Ein einz’ger Puls des Schmerzens

War angefacht

Um Mitternacht.

Um Mitternacht

Kämpft’ ich die Schlacht

O Menschheit deiner Leiden;

Nicht konnt’ ich sie entscheiden

Mit meiner Macht

Um Mitternacht.

Um Mitternacht

Hab’ ich die Macht

In deine Hand gegeben:

Herr über Tod und Leben,

Du hältst die Wacht

Um Mitternacht.

At midnight

I was roused

and looked up to heavens;

No star in the entire sky

smiled down upon me

at midnight.

At midnight

I cast my thoughts

out beyond the dark limits.

No vision of light

Brought me solace

at midnight.

At midnight

I was rapt

to the beats of my heart;

One single pulse of pain

welled up

at midnight.

At midnight

I fought the battle,

of your passion, o humankind;

I could not resolve it

with my strength

at midnight.

At midnight

I commended my strength

into your hands!

Lord, over death and life

You keep watch

at midnight!

—Friedrich Rückert, Um Mitternacht (ca. 1835) in: Ausgewählte Werke, vol. 1, pp. 234-35 (A. Schimmel ed. 1988)(S.H. transl.)

In Musicophilia, Oliver Sacks repeatedly discusses the emotive force of certain kinds of music and attempts a scientific understanding of the phenomenon. Drawing on personal experience at one point, he describes songs that his dream-mind was playing incessantly–they were “songs full of melancholy and a sort of horror.” They were also songs in a language he did not understand. Sacks is talking about Gustav Mahler’s collection of songs composed to poems by Friedrich Rückert–he was focused on the dark Kindertotenlieder, but another equally powerful song is Um Mitternacht. I will have more on this in an interview with Oliver Sacks in the next few weeks.

Like many of Rückert’s works, this one has strong lyrical qualities–if it is not indeed overtly a hymn. The work stands clearly in the tradition of the early Romanticists, and particularly of Novalis and his Hymnen an die Nacht. “Abwärts wend ich mich zu der heiligen, unaussprechlichen, geheimnisvollen Nacht. Fernab liegt die Welt – in eine tiefe Gruft versenkt – wüst und einsam ist ihre Stelle,” Novalis writes – “I turn aside to the holy, unspeakable, mysterious night. The world lies far away, sunk in a deep crypt – desolate and lonely her fate.”

The poem scintillates with emotion, but it suggests a viewpoint that is only half-awake, perhaps in a trance-like or dream-like state. It pulses with anxiety, softened by wonder at the great work of nature. The speaker feels a profound attachment to this world, but also a role of subordination. It concludes with a tone of resignation and a distinct series of religious, particularly Christian notes, evoking words of Christ on the cross and ending with a confession of faith. The turn from awe of nature to religious profession is a distinct mark of the early Romanticists like Novalis or Brentano. Rückert belongs to a slightly later era, but some of his best works, like this one, could pass easily for a composition of Novalis. Mahler’s orchestral setting of this work is a marvel, the use of woodwinds is particularly powerful and evocative. It presents tonally the emotions behind the poem in a way that seems to me to coincide perfectly with Rückert’s design. And Mahler’s orchestration also reflects a transformation–from the intensely personal tonality of the first stanza, opening with the warmth, and decidedly human personality of a single woodwind, building steadily to the ecstatic moment at the conclusion. The end is distinctly communal, it has the feeling of a chorale, with timpani and brass coming in enveloping and overpowering the voice of the soloist. The shepherd-pilgrim of the poem is surrounded by the orchestral host. It is an act of communion in which the individual human voice of the poem almost disappears. The orchestration thus parallels the text, in which a shepherd’s noctural awe of nature and the heavens is shaped slowly into religious conviction in which the individual becomes an integral part of a community of faith, subordinating himself to the creator. But in terms of composition, one can fairly ask if this is still a Lied? It is as the work begins, but by its conclusion the human voice succumbs to the power and force of the orchestra. Mahler has created a new genre, the orchestral Lied.

This poem belongs to the works of a German poet who is usually, despite his lyrical success, only placed on the second rung in the German literary canon–probably unfairly. Nevertheless, this particular work had great impact around the world–winning its earliest acclaim outside of Germany. Its first broad impact was in fact felt in the United States. The New England Transcendentalists, filled with a zeal for the German Romanticists, picked it up almost immediately from its first publication in Germany–it was translated by the Reverend N.L. Frothingham of Boston and widely published in Transcendentalist journals during the period. A letter from Rev. Frothingham to Rückert from 1837 discussing the translation can still be found in the Rückert Archives. The themes of the Rückert poem in fact resonate in several essays and poems by Emerson from the same period. American anthologies of the period regularly speak of the three great contemporary German poets–Goethe, Schiller and Rückert–a distinction that Rückert failed to achieve at home, but perhaps one that was merited.

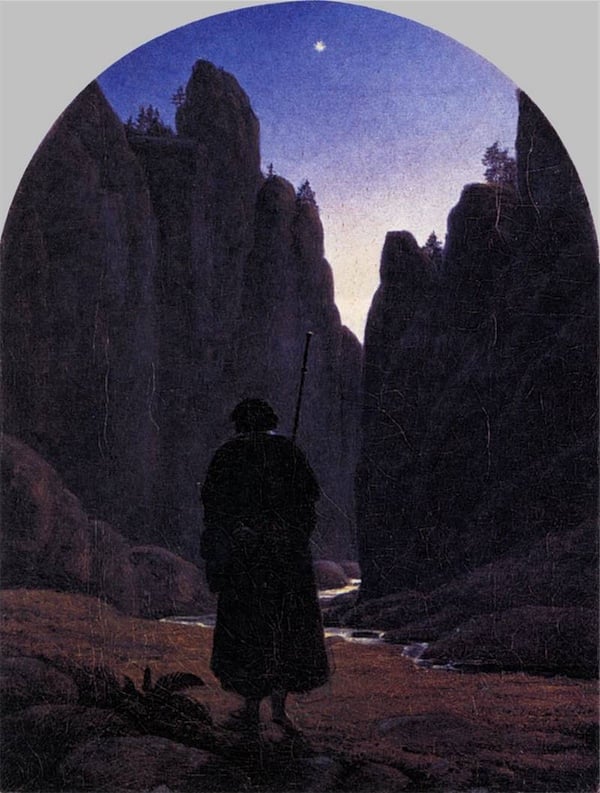

I have long associated Rückert’s poem with Carus’s painting of a shepherd on a nocturnal voyage, staff in hand. Rückert in fact describes his work as a “Hirtenlied,” a shepherd’s song. But Carus’s painting captures perfectly the imagery and illuminates the strong psychological undercurrents of the narrative. Carus, a friend of Goethe’s who learned painting as an understudy to Caspar David Friedrich, was in fact a physician and pioneer of psychology (he coined the use of the term “unconscious” in its current psychological sense, for instance). He was also taken with the psychotherapeutic value of painting and music. He particularly believed that painting could allow an artist to portray and explore images from the subconscious. There is no doubt that Rückert is attempting something like this with Um Mitternacht. In a sense the progression from the age of Novalis, Rückert and Carus to that of Mahler, Freud and Schnitzler is logical–a linear progression. This is one of the reasons why Mahler’s choice of these poems in 1899 was so effective. He correctly recognized in them a link to the world of psychoanalysis which was being launched all around him. And just as Rückert’s poem was launched in Germany but found success in America, so Mahler’s orchestrations were first performed to controversy in Vienna and found greater critical acclaim when Mahler moved to New York just a few years later.

Mahler’s music and Rückert’s poem are an effective combination. There is very little in the entire Lied literature which can begin to compete with them.

Listen to Jessye Norman sing Gustav Mahler’s setting of Um Mitternacht in a 1990 performance at New York’s Avery Fisher Hall. Zubin Mehta conducts the New York Philharmonic: