Omnino qui rei publicæ præfuturi sunt duo Platonis præcepta teneant: unum, ut utilitatem civium sic tueantur, ut quæcumque agunt, ad eam referant obliti commodorum suorum, alterum, ut totum corpus rei publicæ curent, ne, dum partem aliquam tuentur, reliquas deserant. Ut enim tutela, sic procuratio rei publicæ ad eorum utilitatem, qui commissi sunt, non ad eorum, quibus commissa est, gerenda est. Qui autem parti civium consulunt, partem neglegunt, rem perniciosissimam in civitatem inducunt, seditionem atque discordiam; ex quo evenit, ut alii populares, alii studiosi optimi cuiusque videantur, pauci universorum.

All those who would assume the mantle of public affairs would be well advised to heed two of Plato’s rules: first, to keep the best interests of the people so clearly in view that, whatever their own interests, those of the people will guide their conduct; and second, to care for the well being of the whole body politic, and not that of any one political party, especially not one which is prepared to betray the interests of the state for its own gain. The administration of the affairs of state must be taken like a public trust, to be undertaken for the benefit of those entrusted to one’s care, and not for the benefit of those upon whom the trust is conferred. Indeed, those who undertake the charge of government for the benefit of their political party while neglecting other parts of society infect the public calling with a dangerous virus–they introduce discord and sedition. If some adhere to the party of the plebes, and others to the elites, then few will serve the needs of the state itself.

—Marcus Tullius Cicero, De officiis, lib i, cap xxv (44 BCE) in the Loeb Library edition of the Works of Cicero, vol. xxi, p. 86 (S.H. transl.)

On July 11, 2007, a senior White House staffer, Sara Taylor, appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Defending her position under hostile questioning, she insisted “I took an oath to the president, and I take that oath very seriously.” Didn’t she mean she took an oath to defend the Constitution, corrected the committee chair, Senator Patrick Leahy? Leahy, of course, was correct–the oath prescribed for government officials is to the Constitution, not to the president. It would be easy to write the incident off as a simple flubbing of facts, the sort of mistake a witness under the pressure of a televised Congressional hearing might forgivably make. Still, Taylor was not the only Bush Administration official to make just this mistake, and it was a telling one. Many of the most controversial episodes of the Bush era involve fidelity to the president being put above the law and the Constitution–torture was approved, warrantless surveillance was authorized, prisoners were held for years without charges or access to court, for instance. Moreover a group of U.S. attorneys were fired precisely because of suspicions that they placed their loyalty to the Constitution above their fidelity to the president and their party. So what consequence should we give that oath that Taylor so dramatically misremembered? Is it a mere footnote, a formality? Or does it not reflect in a deeper way what we expect of government officials and the values against which their deeds must be measured?

In the fall of 44 BCE, the Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero was shuttling anxiously between his estates. He was placed under proscription by the triumvirate that ruled Rome and he feared for his life–properly, it seems, for in a few months he would be assassinated by order of his enemy Mark Antony, the man he skewered for all eternity in the Philippics. This was a period of exceptional creativity for Cicero, much of it driven by his concern for the Republic and his obsession with efforts to salvage it. He wrote De Officiis (On Duty), in the form of a letter to his son, though it’s clear it was intended for a wider audience. It is an important work of moral philosophy, but at its core are notions of responsibility for those who assume public office–what are the duties they owe, and to whom. The work is filled with timeless wisdom, but it is also a manifesto–how to preserve the essential spirit of the Republic in the face of an autocratic onslaught. Cicero approached his subject in just the way his own life would have suggested: he argues that those who aspire to govern must approach their goal with an attitude of sacrifice and service, not of privilege and right. They should demonstrate their fidelity to the community and their competence by a life of service, starting with humble posts. A career cannot begin with a campaign for election to high office. (Sed iis qui habent a natura adiumenta rerum gerendarum abiecta omni cunctatione adipiscendi magistratus et gerenda res publica est; nec enim aliter aut regi civitas aut declarari animi magnitudo potest. lib i, cap xxi). Cicero also views partisanship as the natural enemy of sound public service. Those who use public office to advance the interests of their party rather than society as a whole are dangerously undermining it. And he stresses the role of justice because no officeholder can be successful without a strong sense of it. “Justice,” he writes, “consists of doing our fellow humans no injury, and decency of giving them no offense.” (Justitiæ partes sunt non violare homines, verecundiæ non offendere, in quo maxime vis perspicitur decori. lib i, cap xxviii.)

What would Karl Rove make of this nonsense? And what would Rahm Emanuel make of it? Political offices are for those who serve their party, and increasingly for those who put the party’s interests first. Ambassadorships, for instance, are for those who have raised solid six-figure sums for the quadrennial presidential war chest, or at least that is the practice that has steadily evolved since World War II, even as the price tag climbs. And officeholders need to be team players who understand that the president is their captain. Cicero understood this tendency, for even in his day offices were bought and sold and distributed as the essential underpinnings of a patronage system. But he viewed it as a corruption: how the public servant understands his office and his responsibilities is decisive for our society. In no small part, it is the dividing point between a republican form of government and an authoritarian state.

When America’s Founding Fathers had won their revolution, they were presented with a challenge. What oath should be sworn? The oath binds the holder to his office, but by practice and tradition it went far beyond mere legality, imparting moral duties as well. As British subjects they were used to swearing an oath of personal fealty to the Hannoverian monarch. Surely the president should swear an oath to the Constitution, but what about those who served him? Should they not swear an oath to the president? But the Founding Fathers knew Cicero, and they knew De Officiis–the oath which was to be taken must describe the essence of the new state and the relationship that the officeholder had to it. Setting the president up as a substitute for the king would be an act of betrayal. The firebrand Thomas Paine furnished the answer in Common Sense:

But where says some is the king of America? I’ll tell you Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal of Britain. Yet that we may not appear to be defective even in earthly honors, let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the charter; let it be brought forth placed on the divine law, the word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the king is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other. But lest any ill use should afterwards arise, let the crown at the conclusion of the ceremony be demolished, and scattered among the people whose right it is.

In 1789, the First Congress prescribed first the oath for civil servants and then, in the Judiciary Act, for judicial officers, providing in its core “I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent on me, according to the best of my abilities and understanding, agreeably to the Constitution, and laws of the United States.”

Cambridge University Press has just published Steve Sheppard’s new book I Do Solemnly Swear, an inquiry into the moral obligations of legal officials. Like Sir Edward Coke before him, Sheppard has taken a series of quotations from De Officiis as the epigram for each chapter, which in a sense is an extended meditation on Cicero’s text and an ample demonstration of its modernity. The work is a wonderful discussion of material that is, to our lasting harm, long underappreciated.

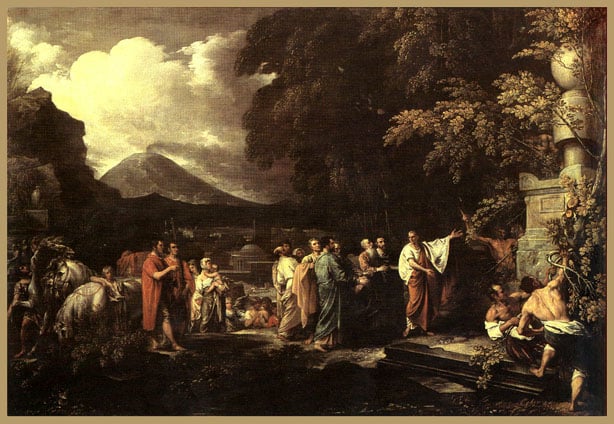

While serving as a quæstor (inspector general) in Sicily at the outset of his career, Cicero brought charges against the provincial governor for corruption and secured his conviction and removal, which led to Cicero being recognized as one of the great public integrity prosecutors of his age. At this time he also discovered the tomb of the great mathematician Archimedes and paid homage to him. Benjamin West, a Pennsylvania artist who made his career in London, portrayed the scene in this Neoclassical work from 1797, executed using what West considered to be Venetian techniques from the age of Titian. In 1804, West reexecuted the painting in his own style.

Listen to a performance of Johann Sebastian Bach’s motet “Der Geist hilft unsrer Schwachheit auf” BWV 226 (1729). The theme is thanksgiving for a life of faithful service, it was composed as a memorial for the rector of the St. Thomas School, Johann Heinrich Ernesti. The text is taken from Romans 8:26-27. Here the work is performed, just as the original was, by the Boys Choir of the Thomaskirche in Leipzig.