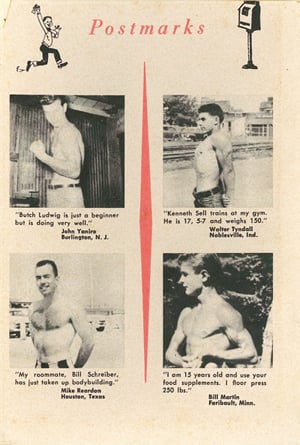

Bottom right: The author’s father, ca. 1955

My father’s first job after being expelled from college was managing a Gold’s Gym in Minneapolis. Later, whenever we visited him on Palm Beach or in Scottsdale, he would pull out photocopies he’d kept of the gym’s workout sheets and create a workout for each of us—me, my older brother, Darren, and my little brother, Pat. Then we’d “hit the gym, boys.” As long as he was alive, even after he’d told me he feared he was losing his mind, he would join gyms and work himself into shape. For his fiftieth birthday, he set up a photo shoot for himself, putting on a Speedo and striking various embarrassing young-Schwarzenegger poses for a series of sharply etched black-and-white pictures. (Arnold Schwarzenegger was a great hero of my father’s, along with many other bodybuilders whose names I no longer remember despite the muscle-magazine subscriptions he bought me from the time I was six or seven until I was in my teens and had the courage to ask him to stop.) The photos emphasized his pectorals, his biceps, the broad muscles of his back—those wing-like muscles bodybuilders cultivate. He was always an upper-body man. “Your grandfather cursed me with these spindly calves,” he’d complain. “I can floor press more weight than any other musclehead at my gym, but my legs will never look like a real weightlifter’s. Your old man could have been a great bodybuilder, son, if it weren’t for these damn calves. He gave them to me and I gave them to you. We can run like the wind—at least, your brothers can—but we’ll never have the muscle structure we need. Of course, with your shoulders you could have one helluva build if you’d apply yourself. Maybe this summer you’ll get serious about it.”

You will notice in the above photo that my father does not show his legs. The picture was taken in Faribault, Minnesota, where he had been sent from his home in Winnipeg to attend Shattuck, a prestigious prep school favored for bad rich boys. (“The same school they sent Marlon Brando, son,” he told me when we visited it together one summer.) As a boy I admired the photo often, because it was so clear to me that the other three young men depicted were not in the same league as my father. When I was fifteen or sixteen I would look at it and think, as one does about one’s father, “There’s why I will never be the kind of man he is. There’s why I can never do what he can do, what he has done.” Looking at it now, as a man with a seventeen-year-old daughter, I wonder what ferocity, determination, discipline, insecurity, ambition, or self-hatred led a fifteen-year-old boy to create a body like that. He was already a famous athlete for his age in Manitoba, and I saw his name on various trophies in Shattuck, where he still held the school record for most touchdowns scored in a single game. Four touchdowns. The madness my mother later insisted was already present in him as a teenager shows in that body to me now. It is the teenaged body of a man who will die in the midst of mystical visions and under suspicious circumstances in the psychiatric ward of a county hospital for indigent patients.

Clancy Martin is a contributing editor of Harper’s Magazine. His memoir “My Old Man” appears in the June 2012 issue.