The Tutelage of Charlotte and Emily Brontë

The Brontë sisters’ devoirs on filial love, under the instruction of Constantin Heger

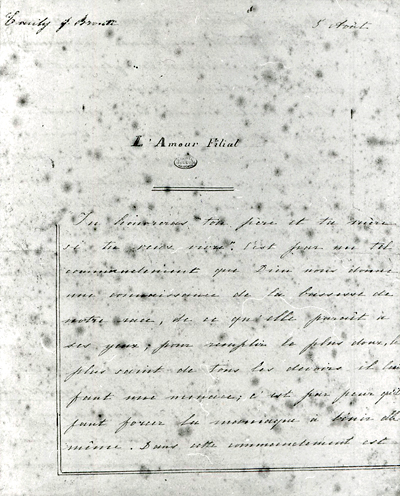

Charlotte Brontë wrote “L’Amour Filial” in 1842, during the first of two years she spent at the Pensionnat Heger, a boarding school for “jeunes Demoiselles” (“young ladies”) in Brussels. At twenty-five, she was an over-age student, but she and her twenty-three-year-old sister, Emily, had come to Belgium with a purpose: to improve their French and so become more qualified to open a school of their own in Haworth, the village in Yorkshire where they had been raised. This three-page essay is one of many devoirs (assignments) Charlotte wrote for her professor, Constantin Heger, but, unlike the others, this one came to light only last year when a document written in faded brown ink was found in a private library. The essay was presented to members of the Brontë Society in June this year; my translation of it in Harper’s Magazine marks its debut before a wider audience.

Filial love was an important topic for both the Brontës and the Hegers. Patrick Brontë, father of Charlotte and Emily, was the Anglican clergyman of Haworth. Widowed when his youngest child, Anne, was not yet two years old, he raised five daughters and a son alone. Before they reached their teens, the two oldest daughters died of tuberculosis. Still, the lives of the remaining siblings were far from gloomy. They had the run of their father’s library, they wrote poems and stories about mythical kingdoms, and they played on the surrounding moors. Of course, they also attended church regularly.

Constantin Heger was also a widower; his first wife and infant son died of cholera. But unlike Patrick, who never remarried, Constantin took a second wife, Zoë Parent, in 1836. By the time the Brontë sisters arrived at the school founded by Parent at which Constantin taught, the Hegers had three children; a fourth was born six weeks later. The family had its quarters in the building that housed the school, so Charlotte would have seen Heger’s wife and children there and in the spacious garden. This did not stop Charlotte, however, from falling in love with her Catholic professor, the man whom she would later call “the only master I have ever had.”

“Filial Love” is a pervasively religious exercise in far-from-perfect French about the necessity of loving one’s parents and the dire fate awaiting those who don’t. Still, set in context, the manuscript offers surprising insights into Charlotte’s life and character — particularly since, on the same day in August, Emily Brontë submitted her own “L’Amour Filial” in response to the same assignment. (This devoir has been in Haworth since 1929, as part of the Bonnell Collection.)

Despite the narrow guidelines evidently imposed by Heger, and despite the brevity of the sisters’ responses, the essays are by no means identical twins. While each begin with the Biblical commandment to honor one’s parents (Exodus 20:12), Charlotte uses the standard King James version; Emily’s is the dire “Honor thy father and thy mother if thou wouldst live,” probably taken from a Jesuit version that Heger would have quoted. Where Charlotte sees within these words “the double stimulus of a threat and a promise,” Emily fixates on their darker implications: “It is by such a commandment that God gives us knowledge of the baseness of our race . . . it is through fear that the maniac must be forced to sanctify himself.” Charlotte’s imagery (“he who bites the hand that has fed them”) appears clichéd next to Emily’s prose (“the mother whom they kill by the cruelest of deaths, turning to poison [her] limitless love”). Charlotte’s reasoning is standard: crime will be punished. Emily’s is complex and provocative: the virtuous should “shun with horror” the monster who lives in “a moral chaos” but should still “weep for his fate — he was their brother.” (It may not be incidental that her own brother, Branwell, had become an alcoholic and a bitter disappointment to his family.)

The most obvious difference between the two manuscripts is that Emily’s is free of corrections by Heger, while his markings appear on all three pages of Charlotte’s essay, so that, between the lines, a master–pupil dynamic emerges. In 1856, he told Elizabeth Gaskell, the novelist who was writing Charlotte’s biography, that he “rated Emily’s genius as something even higher than Charlotte’s.” Still, throughout the months both sisters spent at the pensionnat, Heger paid much more attention to Charlotte’s work, possibly because, unlike her disaffected sibling, she responded with flattering compliance. The more he critiqued and corrected her writing, the more she attempted to please him. (As she later wrote in a poem, “Obedience was my heart’s free choice/ Whate’er his word severe.”)

Her only resistance to Heger arose obliquely. Charlotte, who had never met a Catholic before now, found herself immersed in a Catholic milieu; her revulsion to it is clear in her devoirs, as she brandishes her own faith and her Protestant knowledge of scripture. Heger’s corrections sometimes tone down her ardor; in “L’Amour Filial,” for example, he deletes the sentence, “It is holy because Jesus Christ himself has given us the example; in dying he thought of his mother, in his mortal agony he commended her to the protection of the disciple whom he loved” (John 19:25–27). But since this phrase takes the essay off on a tangent, his objection is probably literary. For Heger, a devout yet tolerant Catholic, respected the earnest little Protestant (“nourished on the Bible,” as he later said to Gaskell), and his concern for her improvement as a writer of his language never wavered.

Evidence of that concern appears throughout Charlotte’s “Filial Love.” While some of his corrections are grammatical — changing a verb tense here, adding a pronoun there — he ignores six missing accent marks and other minor lapses, apparently preferring to embellish her commonplace phrasing. He substitutes “a sentiment of nature” for “instinct,” “a legal prescription” for “a duty,” “scruple” for “doubt,” “existence” for “life,” and “nurtured” for “cherished.” As he works through Charlotte’s pages, his enthusiasm seems to intensify so that, by page three, he, too, is reviling the miscreant child who fails to respect his parents (“a horror to mankind!” he writes above her handwriting, “woe betide him!”).

What effect might Heger’s attention have had on Charlotte? The answer is plain to those familiar with the letters she sent him after she returned to Haworth, letters that caused a scandal when they were made public in 1913. (Until 1844, when the first of Charlotte’s four letters reached him, Heger apparently remained unaware of the feelings he had evoked.) Charlotte was coming to crave his words on her page; his criticism fed her devotion, and she could not contain the kind of emotion that underlies this text’s strangest sentence (“the child can love his mother without fear of loving too much; no doubt torments that kind of affection; it is pure, and therefore it is tranquil…”). Six years later, the author, perhaps recovered, perhaps not, would transpose that conflict onto another studious young woman whose master “stood between [her] and every thought of religion, as an eclipse intervenes between man and the broad sun.” As Jane Eyre continues: “I could not, in those days, see God for His creature of whom I had made an idol.”