Darling: A Conversation with Richard Rodriguez

Richard Rodriguez on the essay as biography of an idea, the relationship between gay men’s liberation and women’s liberation, and the writerly impulse to give away secrets

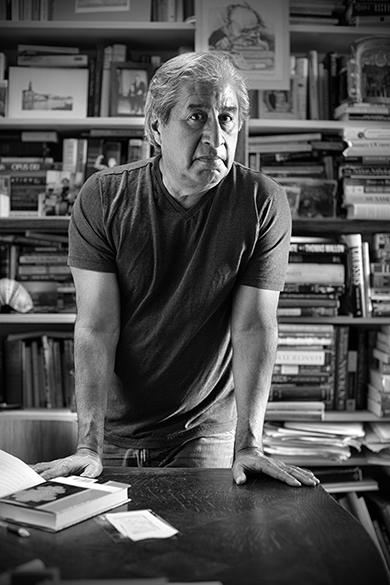

Richard Rodriguez is one of Harper’s Magazine’s best-loved essayists. (Readers unfamiliar with his work might start with “Late Victorians,” still as poignant as when it was first published in our October 1990 issue, and then read everything else.) Born in San Francisco to Mexican immigrant parents, he spoke almost no English until he attended a Catholic school at the age of six, when he was introduced to what he calls the “public language of los gringos.” As a Ph.D. candidate in English Renaissance literature at the University of California, Berkeley, Rodriguez renounced academia, angered by the culture of affirmative action and wary of benefiting from his status as a “minority student” — a dilemma he discusses in his first book, Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez, which was published in 1982. His next works, Days of Obligation: An Argument with My Mexican Father (1992) and Brown: The Last Discovery of America (2002) similarly combined personal experience and social commentary, which is to say nothing of their poetry and charm. Rodriguez’s latest book, Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography, was inspired by his bewilderment following the 9/11 attacks. It is an essay collection that ostensibly explores the Abrahamic “desert” religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, but that also draws us, in Rodriguez’s characteristically associative style, into his own history and in particular his relationship with women. (An excerpt is available here.) When I spoke with him, he was sitting in the San Francisco apartment where he has lived and worked for the past thirty years — “happy,” he said, “as the spring.”

RR: Have we started?

ES: The interview? I think so, yes.

RR: I remember once watching Rose Kennedy, the president’s mother, on television. She did an entire interview and then asked, “Well, when do we start?” And the interviewer said, “We just finished.”

ES: She probably gave a great interview because she didn’t know she was “on.”

RR: That’s right. She was a bit dizzy, but true, and quite charming for being so unpretentious. One could imagine happily sitting next to her at an otherwise tedious dinner party.

ES: Tell me — how much do you know about an essay before you start writing?

RR: Well, sometimes I use my inexperience or lack of knowledge as the drama of the essay. The essay becomes a kind of biography of an idea — how it reveals itself and comes to a fullness. The essay can begin with inexperience, and as it teaches the reader, so also it teaches the writer. There’s something very exciting about that kind of progress.

Other times I write an essay because I am struck by something. I remember, after September 11, I was struck by the notion that the monotheistic religions of Abraham are desert religions. That is what the terrorists taught me, as they prayed to Allah. They had come to New York and to Washington from desert countries to bring havoc to our lives. Slowly, it occurred to me that the God of the Muslims, who is also the God of the Jews and the God of the Christians, is a desert God.

As a Roman Catholic, I suppose I had long traced my religion to Europe. After September 11, what I realized was that the God I worship had disclosed Himself to Abraham within an ecology of desolation. You know, the non-believer smirks and says, “You foolishly pray in such a place — there is nothing there.” But the believer faces a different question: “Why would God reveal Himself within such a desolate ecology?” That’s the idea that came to me driving down a freeway in California, and the essay followed.

Another way an essay comes into being is when one is tricked by the essay’s complexity. I suppose I began writing Darling expecting that my homosexuality would play against the orthodoxies of the desert religions. But as I wrote, I surprised myself by becoming more interested in women and the desert religions and my relationship as a homosexual man to heterosexual women.

I dedicate my book to the order of nuns that educated me, the Sisters of Mercy. Running schools and hospitals and orphanages in my youth, they were the first feminists I knew — though they would probably have shied from that term. By whatever term you want, they were able to move in the public world precisely because they didn’t belong to the conventional public world. They were dressed like Muslim women in black robes. Their robes were their freedom in a world of men.

As the idea expanded, I began to appraise my adult friendships with women — and in particular with a particular woman I call “Darling.” All I want to say now is that this was not a relationship I had expected would end up in my book, and at the very center of my book.

ES: The relationship between women and gay men has come up quite a bit recently in relation to the Church.

RR: Yes — like a number of my friends, I was relieved to read the interview in America Magazine where Pope Francis admitted that maybe the Church has been overly preoccupied with gay marriage and abortion. Though he didn’t venture from orthodoxy in either case, he did make clear that there is more to Christianity than these two issues. The question the Pope did not go on to ask is “Why?” Why has the Church been for so long preoccupied by abortion and homosexuality?

You know, women are arrested in Riyadh for driving a car. A young girl in Pakistan gets shot in the head on her way home from school. The woman or girl who rejects the cloister of the house is in danger in many desert cities. What is the male anxiety in these instances?

The woman who refuses to give birth, chooses to terminate a birth, represents a violation of the natural order for many in America. The homosexual male — the feminized male — becomes a sort of accomplice to the woman who will not submit to automatic motherhood.

My sense is that, instead of the Stonewall riots in New York, the real liberation of gay men began a century earlier with the processions of women in European streets and in North America demanding the vote. The women who left the parlor anticipated my escape from the closet. And some of the most conservative Christian churches have seen the connection. After all, after September 11, the Reverend Jerry Falwell counted American feminists and homosexuals among those who were responsible for bringing the wrath of God upon our nation.

ES: I suppose that, from a formal perspective, the women in your collection provided a kind of embodied form for some of the more abstract ideas you write about.

RR: That’s right. I experience many of the ideas in my Darling through experiences that were fleshy. My abstractions about homosexuality and feminism, for example, come within a chapter otherwise concerned with a late-afternoon lunch of club sandwiches in Malibu with a friend on the day her divorce was finalized. . .

I don’t know how else to write. Partly because of having grown up in a house in where there were no books — I could never describe to my parents exactly what it was that I was preoccupied by. The question I always ask when I speak to an audience is, “Do you know what I mean?” I have a profound sense that no one quite knows.

ES: This collection seems more than ever a quest for a common language or humanity.

RR: Quite literally sometimes. One of the ironies of traveling within the Arabic world has been that my confrontation with the stranger became a discovery about myself. As I got closer to the Arabic language, I began to hear echoes of Spanish. My first chapter I call “Ojalá” — the expression my Mexican mother often used to mean “Let’s hope it may be so” — which is derived from the Arabic commonplace prayer: Insha’a Allah. The Spanish language has as many as three or four thousand words that are etymologically Arabic in derivation. So the journey toward the stranger’s tongue led me to hear my mother calling out “ojalá” as I left the house for school, decades ago.

But to answer your observation less literally — yes. I am looking for some basis of connection between men and women. Some readers will find that an irony — that a gay man seeks connection with heterosexual women. But beyond sexual difference and obvious sexual passion, what I sense is a compatibility or, as you say, a common humanity.

ES: There are a couple of essays in the collection in which you address a particular woman — Ahuva in “Jerusalem and the Desert” for instance, or the woman you call “Darling.” Do you have a particular reader in mind as you write?

RR: I try not to particularize the reader. In fact, though the woman I call “Darling” has died, what I worried most about was that her children would recognize their mother from my essay. I worried, as well, about her husband, who remains a friend. So I disguised details of my friendship with Darling — like the fact that she invited me into her bed, for example. I wrote to her children to assure them: “This is your mother and not your mother. I have fictionalized details…”

It would have been paralyzing for me to imagine her son and daughter reading the chapter otherwise. So I had regularly to remind myself that I wasn’t writing for Darling’s children but rather for a common reader who knew neither of us.

ES: But are you also drawn to giving away secrets?

RR: Yes! I confess. In my defense, I think that there are some things so personal that they can only be told to a stranger. As a scholarship boy, I knew, for example, that the very anonymity of the writerly “I” gave me a freedom in the city of words to tell family secrets to strangers, and this freedom was crucial to my ability to venture away from the house.

ES: In “Tour de France,” you confess to having been the boy who in fourth grade told your best friend’s secret to get a laugh.

RR: Yes — and worse, I don’t remember now what the secret was! I am often haunted of late, as I progress toward the end of my life, by the thought that I will end up with only a public life, having betrayed so many in my private life.

ES: Tell me about the presence of death in this collection. Does death make you want to write?

RR: You know, as a Mexican, and as someone formed by Mexican culture, death was ever-present in my life. Similarly, it was death that Irish Catholics at my parish church spoke of. They didn’t use the American euphemism of “passing away.” Nobody passed away in either my Irish-Catholic or my family’s Mexican life. People died. It was death I knew and death I literally carried to the grave. As an altar boy I sometimes helped mourners take a casket to the gaping hole in the earth. As a gay man, I poured morphine down a friend’s throat as he moved from pain to death. That experience would make me ever after reluctant to give myself the adjective “gay.” As I told a television interviewer once, I don’t consider myself a “gay writer”; I am a morose writer — more comic than gay, I suppose . . .

Oh, what extraordinary things I have seen! My mother dies one night and the floor lamp at the foot of my bed — it has a switch that has to be twisted — suddenly turns itself on!

ES: In “Ojalá,” you mention Caryll Houselander, the English artist, writer, and bohemian, who had a mystical experience on her way to pick up the potatoes.

RR: Yes, I love that. I think the great vision of the Divine comes to children or to Houselander — a teenager. How else can complexity and mystery enter our world except through such simple lives?

ES: It reminds me of the famous vision of Julian of Norwich — that image of the world as a walnut in God’s hand.

RR: Yes, wonderful! One of the reasons I like the short stories of Flannery O’Connor so much is that the “vision” of God often comes in a moment of greatest humiliation; at exactly the moment when the woman has her wooden leg stolen by a criminal Bible salesman, she is made to crawl, and then she sees . . .

Yes, whenever I read in the morning paper that a statue of the Virgin Mary has been found to be weeping, I get in the car and take a look.

ES: Is there a relationship for you between writing and praying?

ES: Is there a relationship for you between writing and praying?

RR: I agree with Thomas Aquinas who describes the act of writing as a kind of prayer. Certainly as a person who writes every day it does seem to me that the energy, the inspiration, comes from outside of myself. Yesterday I struggled with this paragraph and nothing came. Today, the words come freely and almost seem to write themselves . . . so, like other writers, I come up with metaphors like grace and the muse and inspiration to explain how it seems that something outside my own efforts had produced the line I could not write by myself.

I don’t mean to become such a— I’ve never liked the word “piety.” And I don’t even like it when people say about me that I am a good man. I just, it makes me nervous — there’s a kind of domestication about such praise. For myself, I prefer the raggedness of my life of faith. I like to consider Andy Warhol a saint, one of the great saints of my lifetime. And I look for God in places like, you know, gay bars, where maybe no one else expects to find Him, in the dark.