Warthogs and All

The U.S. Air Force’s foolish plan to scrap its most effective plane

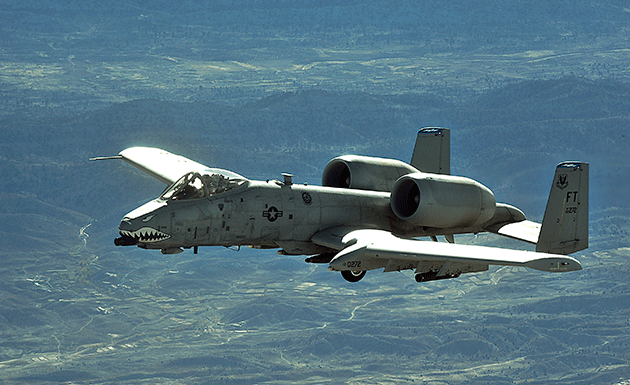

A U.S. Air Force A-10 Thunderbolt II “Warthog” in-flight over Afghanistan, October 7, 2008. ©© Staff Sgt. Aaron Allmon (via Flickr)

According to legend, it was airpower that conquered Afghanistan back in 2001, with the Taliban sent packing after a few weeks of precision strikes from U.S. warplanes. Now it looks as though airpower is playing an important role in turfing us out of the country, with the reborn Taliban snapping at our heels. The January 15 airstrike in Parwan Province, which according to the Afghan government killed at least twelve civilians, including seven children, allegedly inspired a retaliatory Taliban attack that killed twenty-one people at a Kabul restaurant last week, most of them foreigners. President Hamid Karzai is now demanding that all U.S. and allied airstrikes cease forthwith.

We don’t yet know the details of the Parwan strike, for example the type of aircraft used. The promised investigation will take a long time, and its conclusion will doubtless be classified. But the details of an equally disastrous attack in May 2012, reported exclusively in my piece “Tunnel Vision,” in the February issue of Harper’s Magazine, tell us a great deal about how such events occur.

That strike occurred in Paktia Province, close to the Pakistani border, and it was inflicted by a B-1 bomber, a plane originally designed to drop nuclear bombs on Moscow. The target was a farmhouse inhabited by a man named Shahiullah and his family. The payload of several tons of bombs killed him, his wife, and five of his seven children. The ground controllers directing the attack, and the crew of the B-1, had been informed that only civilians were at the scene, and that this was a “bad target.” This information came from the one plane in the U.S. arsenal designed specifically for close air support of troops on the ground: the A-10 “Warthog.” Two A-10 pilots had spent many minutes circling low over the farm, scanning it at close range with the naked eye and through binoculars, then warning repeatedly that it was a bad target and refusing to strike as ordered. Their warnings were ignored by the ground controllers, who handed the mission over to the willing B-1. As a result seven people, including a ten-month-old baby, died.

With the exception of drone assassination strikes, close air support is the main function of airpower these days. Since targets tend to be close to friendly troops, commanders require precise information about the location and identity of targets. So one might assume the U.S. Air Force would cherish a plane that is uniquely and specifically designed to perform this mission. Such is not the case. Service chiefs appear determined to junk the A-10, which can operate close to the ground because of its armored cockpit; the location of its fuel tanks, which are well away from its engine; and other features that allow the pilot to brave enemy fire at altitudes that would prove fatal to thin-skinned fighters such as the F-16 — let alone a lumbering bomber like the B-1. In addition, the A-10 can fly slowly while maneuvering nimbly. Unsurprisingly, American soldiers and Marines, who are often themselves the victims of inaccurately targeted bombs, cherish the Warthog as a close friend in combat.

In theory, technology has taken care of the problem, with high-definition video screens for targeting, and bombs and missiles that are precisely targeted by GPS or lasers. In practice, things are not so tidy. “People just don’t realize,” one weapons designer commented to me, “that high-definition video isn’t good enough to show the subtle stuff you’ve got to see to keep from hitting your own guys or killing civilians.” He compared the task to watching a Super Bowl broadcast and attempting to determine whether a spectator was leaning on an AK-47 or a cane. The vaunted capability of drones to give operators thousands of miles away a low-flying-bird’s-eye view of the enemy gets unfavorable reviews from pilots. “If you want to know what the world looks like from a drone (video) feed,” an Air Force officer with extensive drone experience told me, “walk around for a day with one eye closed and the other looking through a soda straw.”

The consequences are frequently bloody. In a particularly deadly attack in May 2009, bombs from a B-1 killed at least 140 men, women, and children in Farah Province because the pilot, according to the Pentagon’s own explanation, “had to break away from positive identification of its targets” — i.e., he couldn’t see what he was bombing. Other mass-civilian-casualty incidents during the Afghan war, such as those in Kunduz (2009, ninety-one dead), Herat (2008, ninety-two dead), and Kunar (2013, ten children), can be traced to the same fatal dependence on video-screen images and inaccurate second-hand information from the ground.

As I explain in my Harper’s feature, the Air Force’s decision to junk the A-10 while retaining the B-1 and the even more unwieldy B-52 bombers for close air support may seem inexplicable, but it is in reality quite logical. The service owes its independence from the army to its success in marketing the notion that bombing an enemy heartland far from the battlefield can win wars. The principle of close air support for ground troops negates this core ideology. That is why the Air Force is junking the A-10. It claims it will save $3.5 billion over the next five years by removing the planes from service, but it is simultaneously planning to start a new long-range-bomber program that will cost at least $81 billion, and almost certainly many times that amount.