On Hypocrisy

Should we condemn hypocrites, when we can’t help but be hypocrites ourselves?

I’ve been thinking about hypocrisy, because of Woody Allen, my wife, and a friend of mine who is in the middle of a custody battle.

When my wife first told me about Dylan Farrow’s accusation that Woody Allen had molested her, I said, “Come on, the guy married his stepdaughter, it’s creepy.” She protested that it hardly meant he was a child molester. I rolled my eyes.

Meanwhile, the soon-to-be-ex-wife of a friend has accused him of molesting their children. Or rather, said that she was willing to accuse him of it. That it “seemed like a possibility.” That she felt sure “he didn’t want to get a judge involved.”

I was outraged at this. Furious. I knew my friend well enough to know that he would never hurt his children. But I also knew that he was a recovering drunk and had done things while in a blackout that he would never do sober. My wife rolled her eyes.

After I read Woody Allen’s New York Times editorial responding to Farrow, I felt as though I should reconsider. I was sure my friend was innocent (and still am). But I was quick to conclude that Allen was guilty.

Why had I so quickly and cavalierly condemned him for a charge that I believed was impossible when made against a friend? In fact, I was more ethically outraged at my friend’s ex than I had ever been at Woody Allen when I thought he was guilty. The moral tone of my reaction gave it a nastier quality than mere cognitive dissonance. It was hypocrisy.

I tend to judge people who are judgmental; I am intolerant of intolerant people. “Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits,” Mark Twain observed. When I teach ethics in my day job as a philosophy professor, you might say that I make a living out of telling other people how to reform their habits. Ostensibly we are merely analyzing ethical theory: in a class like “Contemporary Moral Problems,” I don’t tell my students that I believe in euthanasia, or support gay marriage, or am conflicted about the moral status of a fetus even as I support women’s access to abortion. But we professors have not-so-subtle ways of letting our students know our actual position. I pretend that I am the impartial voice of reason, when most everyone can see that I have argued much more vigorously and convincingly for the “emerging standards of decency” argument opposing the death penalty than I did for Kant’s argument that the State has a moral obligation to the murderer to execute him (one of Kant’s more ingenious and outrageous arguments).

I admit all of this, and yet I would also maintain that one of my most cherished self-ascribed virtues is that I am not a hypocrite. I genuinely believe that I am quick to admit my inconsistencies, and that I work to identify them. I consider myself to be an unusually sincere person. I think as far as “authenticity” goes, I’m in better shape than most. And I think it’s fair to say that, while I am relatively tolerant of most moral failings, I despise a hypocrite.

I’m in good company in my dislike of hypocrisy. Complaints about it were common in Ancient Greece and Rome: Aristotle’s successor, Theophrastus, wrote a treatise attacking it as a vice, and one of Cicero’s requirements for friendship was that a friend must never engage in “feigning or hypocrisy.”

Etymologically the word can be traced to the Late Latin hypocrisis, which comes from the Greek hupo (under) and krinesthai (to explain), and means to create an appearance that does not really explain one’s motives. Hypocrisy is a form of deception. To be a hypocrite is to be a fraud.

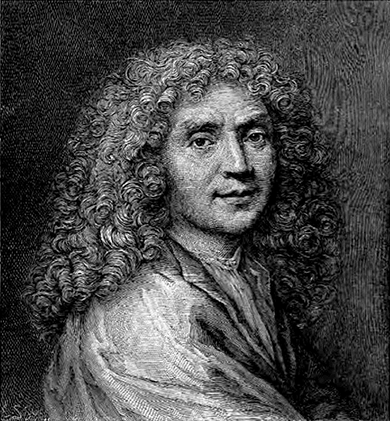

Perhaps the most famous study of hypocrisy in literature is Molière’s comedy Tartuffe, ou L’Imposteur (1664); the adjective “Tartuffian” is still used to point out hypocrisy. To be a hypocrite in Molière’s day was to pretend to hold beliefs — especially religious beliefs — that were contrary to the beliefs one actually held, and so ran contrary to the way one lived. A hypocrite might also act in a way that is contrary to his beliefs, so as to convince others that he holds beliefs that in fact he does not. (As Oscar Wilde said with characteristically contrarian wit: “I hope you have not been leading a double life, pretending to be wicked and being really good all the time. That would be hypocrisy.”)

In Molière’s play, Tartuffe, the hypocrite, is contrasted with Cléante, a pleasant, thoughtful if somewhat unsophisticated fellow who serves a kind of moral compass in the play. Here is Cléante’s great speech against Tartuffe (please forgive the length of the passage, it’s worth it):

There is false piety like false bravery;

Just as one often sees, when honor calls us,

That the bravest men never make the most fuss,

So, too, the good Christians, whom one should follow,

Are not those who find life so hard to swallow.

What now? Will you not make any distinction

Between hypocrisy and true devotion?

Would you wish to use the same commonplace

To describe both a mere mask and a true face?

To equate artifice with sincerity

Is to confound appearance and reality.

To admire a shadow as much as you do

Is to prefer counterfeit money to true.

The majority of men are strangely made!

And their true natures are rarely displayed.

For them the bounds of reason are too small;

In their shabby souls they love to lounge and sprawl.

And very often they spoil a noble deed

By their urge for excess and reckless speed . . .

These people who, with a shop-keeper’s soul,

Make cheap trinkets to trade on the Credo,

And hope to purchase credit and favor

Bought with sly winks and affected fervor;

These people, I say, whose uncommon hurry

On the path to Heaven leads through their treasury,

Who, writhing and praying, demand a profit each day

And call for a Retreat while pocketing their pay,

Who know how to tally their zeal with their vices,—

Faithless, vindictive, full of artifices—

To ruin someone they’ll conceal their resentment

With a capacious cloak of Godly contentment.

They are doubly dangerous in their vicious ire

Because they destroy us with what we admire,

And their piety, which gains them an accolade,

Is a tool to slay us with a sacred blade.

For most of the comedy Cléante is a moderate voice of reason, but at last his frustration with the way the other characters are taken in by Tartuffe drives him to moral outrage. What bothers him in particular is the way Tartuffe uses the appearance of morality — more than morality, piety — to achieve his immoral, impious ends. This is dangerous not merely because it manipulates us, but because it manipulates us in a way that plays on our better natures — and so casts the questions of better natures into doubt altogether. And though Tartuffe is an extreme example of this reprehensible way of behaving, Cléante insists that “the majority of men are strangely made / And their true natures are rarely displayed.”

We will get to that interesting claim about “the majority of men” in a moment. Before we complicate things, let’s look at a couple more complaints against hypocrisy, if only to satisfy my moral indignation about my own moral indignation at my failure to recognize the silly and self-contradictory nature of my moral indignation.

Dante put hypocrites in Malebolge, the eighth circle of hell — especially reserved, as was the ninth circle, for frauds. The hypocrites are with the counterfeiters, seducers, flatterers, sorcerers and simonists, among others. He names Caiaphas — the high priest of Jerusalem, who advised that Jesus be crucified because “one man should die for the people” so that “the whole nation perish not” (John 11:50) — as a particularly egregious example of a hypocrite, because he was only serving his political interests when he advocated the crucifixion of Christ. (In addition to suffering the other torments of the penultimate circle of hell, Caiaphas is crucified in one of the pits of Malebolge). For Dante, as for Cléante, the reason hypocrites are among the lowest of the damned is that their fraud uses the appearance or profession of morally or spiritually praiseworthy behavior to conceal morally or spiritually blameworthy motives and actions. Many of the deceptions we commit are relatively innocuous, but hypocrisies are particularly dangerous for the soul, Cléante says, because “they destroy us with what we admire.” And this in turn causes us to call our moral intuitions, and our faith, into question.

In our own day Hannah Arendt, in her On Revolution (1963), unequivocally condemns hypocrisy:

The hypocrite’s crime is that he bears false witness against himself. What makes it so plausible to assume that hypocrisy is the vice of vices is that integrity can indeed exist under the cover of all other vices except this one. Only crime and the criminal, it is true, confront us with the perplexity of radical evil; but only the hypocrite is really rotten to the core.

For Arendt, a criminal like Josef Mengele or Adolf Eichmann may show us evil in its most terrifying form. Mengele (one fears) may have genuinely believed in what he was doing; Arendt’s most famous book, The Banality of Evil, specifically addresses Eichmann’s apparently sincere, if confused, use of Kant’s moral philosophy in his defense during the Nuremberg trials. Though it disturbs us to admit it, with his sincere but evil intentions and actions Eichmann had a kind of appalling integrity. But the hypocrites among Nazi war criminals (and even ordinary Germans), Arendt says, were still worse, because they couldn’t even appeal to conviction. To act in a profoundly immoral way while recognizing its immorality — and still, to protest one’s innocence! — is the most pernicious of possible moral stances.

Now some hypocrites may do the right thing for the wrong reasons, and that, too, appalled Arendt. That this kind of hypocrisy is morally blameworthy will cause the utilitarians among us to cringe — who knows or cares what the motives are, if the consequences are desirable! — but it does accord with what most of us think when we consider what it means to have strong character. We want good actions to be paired with good motivations. When we think of moral exemplars — the Buddha, Socrates, Mother Theresa, Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela — part of what we admire is that they walked as they talked. We would be feel betrayed to discover a secret diary of Mahatma Gandhi in which he confessed that at night he stalked the streets of Delhi in disguise, punching British policemen in the nose.

The coherence between what one believes and how one acts was, William Hazlitt thought, a sign of nobility, a proof of the fact that a person saw value in himself. To act in accordance with one’s beliefs is an affirmation, most of us suppose, that those beliefs are praiseworthy. By contrast, “a hypocrite despises those whom he deceives, but has no respect for himself. He would make a dupe of himself too, if he could.” Here Hazlitt may be going too far: not only hypocrites, but even the most honest among us are experts at self-deception. As recent research by Dan Ariely (in psychology and economics) and Robert Trivers (in evolutionary theory) has shown, we are in fact a lot better at deceiving ourselves than we are at deceiving others — and one of the reasons we are so adept at deceiving ourselves is precisely so that we can more nimbly deceive others. This is where Cléante and Hazlitt disagree, because Cléante recognizes that part of the pleasure — and part of the moral corruption — of the hypocrite comes from the fact that he knows his words and actions do not reflect his beliefs, and yet he manages to persuade others that they do. If Hazlitt’s hypocrite could deceive himself, he would suddenly find sincerity, we might reasonably suppose, and so no longer be a hypocrite.

But here’s where Cléante’s observation that the majority of men indulge in some form of hypocrisy, and Hazlitt’s suspicion that the accomplished hypocrite would deceive even himself, begin to muddy the moral waters. Listen to Bishop Joseph Butler, who wrote another of the classic studies of hypocrisy, in the seventeenth century:

In common language, which is formed upon the common intercourses amongst men, hypocrisy signifies little more than their pretending what they really do not mean, in order to delude one another. But in Scripture … to ‘use liberty as a cloke of maliciousness,’ must be understood to mean, not only endeavouring to impose upon others, by indulging wayward passions, or carrying on indirect designs, under pretences of it; but also excusing and palliating such things to ourselves; serving ourselves of such pretences to quiet our own minds in anything which is wrong. [emphasis added]

For Butler, the worse and more significant kind of hypocrisy — and the much more common sort, as Robert Kurzban shows in Why Everyone (Else) Is a Hypocrite (Princeton University Press, 2012) — is when we act immorally towards others while deluding them and deluding ourselves.

Here’s the good news from Kurzban, if you can call it that: we’re all hypocrites. We’re hard-wired for it, in much the same way we’re hard-wired for self-deception and other forms of cognitive dissonance. In his straightforward and elegant book, Kurzban explains how contemporary neuroscience regards the structure, psychology, and evolutionary benefits of hypocrisy. Briefly, the self, as Nietzsche once helpfully described it, is a kind of oligarchy wherein different sets of beliefs can be entertained (and even committed to, cherished, defended) depending on the needs of the self in different situations. A brutal tyrant can still be a loving father, because those roles require different and incompatible belief sets.

How on earth does this work? Well, the brain — and thus, on Kurzban’s account, the self — is partitioned. The coordinated brain structures that function to “govern strangers well” or to “hunt deer well,” let’s say, are not fully accessible — and are sometimes completely inaccessible — to the brain structures that function to “raise one’s children well” or “love one’s spouse” or (in contrast with the deer-hunting example) “care for one’s beloved deer hounds.” This partitioning develops not merely because the brain can only focus on and master certain kinds of tasks at particular times, though that’s part of the account. It’s also because the evolved human brain has to become skilled at activities that require incompatible sets of beliefs. To be a brutal warrior demands beliefs and attitudes that are fundamentally different from the beliefs and attitudes needed to be a loving parent.

We might wonder if the brain and the self really can support such radically different attitudes. But Kurzban shows us that even activities as simple as assessment of ourselves and assessment of others involve brain partitioning. We are more generous with ourselves in order to encourage accomplishment, and tougher on others in order to maintain our feelings of achievement. This analysis is supported by a large body of literature on self-deception, and specifically the evolutionary advantages of successful self-deception, which improves our ability to bluff others.

Kurzban convincingly shows that not only was Hazlitt correct that the hypocrite would fool himself if he could, but that Hazlitt didn’t go far enough: most acts of hypocrisy take place while the hypocrite is fooling himself, and even as a part of fooling himself.

But of course we still need others to engage in hypocrisy. “Every man alone is sincere,” Emerson wrote in his essay “Friendship” (1841). “At the entrance of a second person, hypocrisy begins. We parry and fend the approach of our fellow-man by compliments, by gossip, by amusements, by affairs. We cover up our thought from him under a hundred folds.”

Okay, we’ve covered a lot of terrain. We’ve said both why hypocrisy looks like such an ignoble vice and why it may nevertheless be an essential evolutionary and social skill. And we’ve established that, even if hypocrisy is a nasty thing, we ought to be careful in condemning it, because we’re probably hypocrites ourselves — and all the more so in condemning hypocrisy.

Now, all that granted, we should also remember that it doesn’t follow from the fact that something is the case that it ought to be the case — especially when it comes to facts about how we think about ourselves and each other. Let us suppose that Kurzban is right, and we all are hypocrites, for reasons that can be defended. Does that mean Dante, Arendt, and others are wrong to attack hypocrisy?

Think again about my hypocritical posture with respect to Woody Allen’s and my friend’s situations. We have a good explanation for why I acted the way I did: I have one set of beliefs and cognitive skills for judging the people I care about, and another set for evaluating people I don’t know. So my hypocrisy makes sense.

But that doesn’t make it desirable or praiseworthy. This is probably part of what Socrates meant when he famously insisted that “the unexamined life was not worth living”: it’s not until we scrutinize our beliefs, assess their coherence, deliberate between them, and decide which ones are defensible and which should be rejected, that we become fully human, fully moral. Because we are hard-wired, on Kurzban’s account, to form and even cling to inconsistent beliefs (and even models of belief formation), this will no doubt be a lifetime’s pursuit. But nobody said the moral life was going to be easy.

“If you want to know the right thing to do, simply do what is most difficult,” the poet Rainer Maria Rilke once observed, and though that might be a bit extreme — he wasn’t known for his moderation — the basic principle seems well-guided. Yes, it’s going to be tough to have the kind of integrity that Arendt demands. It will require constant self-evaluation. It will make living a moral life a difficult daily project. And the first principle of that kind of integrity will be that, chances are, we can’t judge the behavior of others. Contra Arendt, moral indignation is going to be one of the most difficult attitudes to sustain, so long as we are committed to avoiding hypocrisy. If we believe in at least striving for sincerity and authenticity, we are committed to tolerance; if we want to moralize, we’d best accept our own hypocrisy.