Inside the October Issue

Robert Sullivan on the cult of Hamilton, Walter Kirn on the Republican National Convention, Rachel Nolan on El Salvador's anti-abortion machinery, a story by Joyce Carol Oates, and more

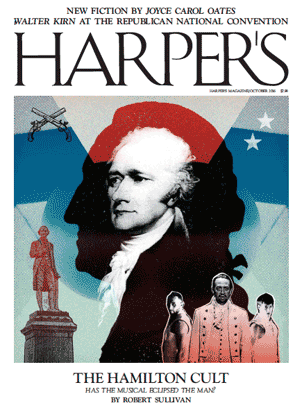

By now, raising any objection to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton is tantamount to treason—you might as well complain about the national anthem, or spit on the flag. The musical has enthralled not only a legion of theatergoers, but politicians, celebrities, historians, and even Robert Sullivan, the author of this month’s cover story. But as he argues in “The Hamilton Cult,” the marvelously talented Miranda has managed to sin by omission. What is absent from the musical, writes Sullivan, is Hamilton’s obsessive focus on military force and wealth concentration as the building blocks of nationhood. More specifically, there is no spiffy song-and-dance number about Hamilton’s quashing of the Whiskey Rebellion—a populist uprising in the Pennsylvania hinterlands and a distant predecessor, one might argue, of the Occupy movement and the Tea Party alike. Debunking Hamilton is not really the point, of course. Sullivan is interested in history and what we do with it. “The past is complicated,” he notes, “and explaining it is not just a trick, but a gamble.” As his essay makes clear, putting all our chips on the Great Man theory is no longer a winning strategy.

By now, raising any objection to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton is tantamount to treason—you might as well complain about the national anthem, or spit on the flag. The musical has enthralled not only a legion of theatergoers, but politicians, celebrities, historians, and even Robert Sullivan, the author of this month’s cover story. But as he argues in “The Hamilton Cult,” the marvelously talented Miranda has managed to sin by omission. What is absent from the musical, writes Sullivan, is Hamilton’s obsessive focus on military force and wealth concentration as the building blocks of nationhood. More specifically, there is no spiffy song-and-dance number about Hamilton’s quashing of the Whiskey Rebellion—a populist uprising in the Pennsylvania hinterlands and a distant predecessor, one might argue, of the Occupy movement and the Tea Party alike. Debunking Hamilton is not really the point, of course. Sullivan is interested in history and what we do with it. “The past is complicated,” he notes, “and explaining it is not just a trick, but a gamble.” As his essay makes clear, putting all our chips on the Great Man theory is no longer a winning strategy.

Speaking of Great Men, or at least theoretically Great Men—our own Walter Kirn made the ultimate sacrifice in July and attended the Republican National Convention in Cleveland. These quadrennial pep rallies have become black holes for even the most diligent journalists. They are staged and sanitized to a fare-thee-well, so that nothing really happens. Reporters are there simply to note the ripple effects on social media and the nominee’s double-breasted, contempt-radiating body language. Yet somehow, Kirn brings the whole extravaganza to life. What’s more, he listens to Donald Trump’s acceptance speech with an open mind, and while the content might be appalling, he can’t help but respond to the delivery: “If he’s acting, he doesn’t know it, which isn’t acting—it’s conducting. His pauses are louder than his bursts of speech and create irresistible spaces for massive clamor. It’s working.” Whether it will work clear through to Election Day is a riddle we’ll be solving very soon.

If Trump is elected, he will appoint the next tranche of Supreme Court justices, which raises the inevitable question: what would it be like to live in a nation without Roe v. Wade? As it happens, there is a test case on hand—a nation where not only abortion but miscarriage has been criminalized to a draconian extent. That would be El Salvador, whose fearsome anti-abortion machinery Rachel Nolan explores in “Innocents.” Her report is detailed, compassionate, and infuriating. How can it be that a woman who has miscarried in a rural pasture—already a sufficient tragedy—is then arrested, tried, and threatened with up to fifty years in prison? How will Salvadoran authorities wrestle with the arrival of the Zika virus, with its attendant threat of microcephaly and other birth defects? There are glimmers of hope here, but El Salvador’s Kafkaesque crusade against its pregnant citizens shows no sign of going away.

Elsewhere in the magazine, Alexandria Neason chronicles the slow-motion collapse and unlikely resurrection of the Detroit school system. In “Division Street,” Robert Gumpert delivers an eloquent and empathetic photo study of the homeless in San Francisco—and while his black-and-white images speak for themselves, they are further enhanced by Rebecca Solnit’s brief introduction. In Readings, Nicholson Baker fails to maintain order in the classroom, and a robot emits a metallic cri-de-coeur: “Why can’t I be considered a person?” We also have Lidija Haas on Nell Zink, whose “cheerfully elastic, almost Walserian deadpan” tends to leave readers in a state of smiling unease, and Matthew Bevis on Thomas De Quincey’s very bad habits, which include substance abuse (to put it gently), voyeurism, and what Bevis calls his “self-relishing archness,” which also makes De Quincey terribly appealing to us navel-gazing moderns.

Last but not least, a reminder: our paywall, erected as a sort of Maginot Line against non-subscribers, has been modified. All visitors to our website can now read one article per month at no charge, and we encourage you not only to dip into Harper’s Magazine, but to share your discoveries on social media. (That’s right, you just saw the words Harper’s Magazine and social media in the same sentence. Despite our fondness for photogravure and pneumatic tubes, we are steadily making our way into the current century.)