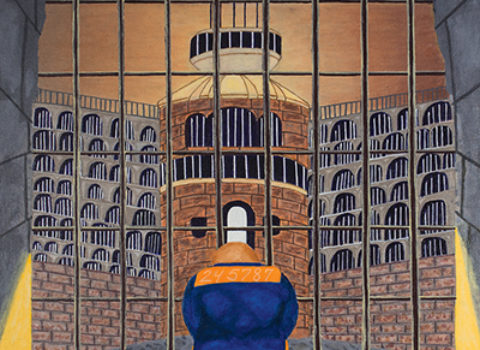

Right after Thanksgiving, red and green decorations start popping up all over the place. The ubiquitous security windows with their diamond-pattern wire reinforcements are suddenly framed in sparkly silver tinsel. It’s 1980, and this is my first Christmas in the joint, in an adult lockup. Everyone who knew me before I entered prison has disowned me. I’m too young to fully grasp what that means.

Tony Huber lives up in the big birdbath cell, so called because it was once a shower room. Back in the Seventies, when the race wars raged hot and bloody, many bodies were discovered in these showers, which were not visible from the guard station. They have since been converted into reward cells, offered to the guys with the most seniority on the wing. Relative to every other cell, the big birdbath is huge, with a tile floor and a window twice or three times the size of the regular ones.

For the holidays, Tony has all of his Christmas cards taped up on his cell wall. There are several dozen, and they’re carefully arrayed, marching from one corner to the next. All the traditional motifs are on display: the Santas and the elves, the trees and the wreaths, the fancy calligraphy with its exaggerated serifs.

The older lifers, now in their forties or fifties and covered in faded tattoos, have similar displays of holiday cheer. Wreaths appear in cell-door windows, handmade Christmas trees are propped up on desks, loud flecks of color are everywhere and stand out against the institutional tans and pale greens. I notice that some of the guards even have candy canes poking from their uniform shirts.

It’s all new to me. On the walls of my cell, I hang nothing. I receive no cards, nor do I send any out. I pass the time reading Nietzsche and sharpening shanks on the concrete floor. Some nights I do a thousand push-ups trying to dissipate the energy; some nights I lie on my bunk confused, overwhelmed by the life I’ve thrown away.

At some point during the holidays, amid the oddly disconcerting peals of seasonal cheer, I’m talking with Johnny Romines. He’s twenty-two, only three years my senior and easier to relate to than the dinosaurs with decades strung out behind them. “Next month, I’ve got four down and only a couple left,” he tells me, as if he were relating what’s for dinner or what crummy movie will be flickering on the chow-hall wall next weekend. I think: “Four years in the joint? That’s a long fucking time. I can’t imagine doing that much time.”

My first Christmas in prison, and I’m living in a state of idiotic denial. I’ve been sentenced to life without the possibility of parole — I was among the first to receive such a sentence in California. It’s so new that the prison system doesn’t know what to do with me. For want of a better solution, I got sent to Soledad, a traditional gladiator school designed primarily to inculcate young men into the prison way of thinking, into the prison way of conducting oneself. I readily embrace this bleak and oversimplified lifestyle. I’m ready to become one of the legion of living dead inside the miles and miles of chain link that separate what is in here from what is out there.

But what of all those cards?

Read the full article here.