Bride Pride is not America’s first mass queer wedding. That distinction probably belongs to a ceremony held three decades ago, on October 10, 1987, when 2,000 couples got “married” in front of 7,000 witnesses on the National Mall as part of a march for LGBT rights. The event was immortalized in a newscast shot by the Gay Cable Network. In the grainy footage, women in lacy white bridal gear and men with handsome Selleck mustaches pose for pictures as “Family,” a song from the musical Dreamgirls, plays in the background.

My uncle David, sporting a blond mustache himself, was one of the thousands on the mall that day. On his way home to San Francisco, he came to meet me and my twin sister, born two months earlier, for the first time. Today, thirty years later, he’s gone, his generation wiped out as much by political neglect as by a virus. And on a sunny weekend in mid-October, I’m on my way to Provincetown to be a spectator at another mass gay wedding: the first ever “Bride Pride: The World’s Largest All-Girl Wedding and Renewal Ceremony.” The event is aiming, as the name suggests, to set the world record for a mass lesbian wedding. There’s just one big difference: it’s legal.

I’m not exactly the most likely front-row attendee at a mass lesbian wedding. I’m one of those queers who’s critical of the institution of marriage, not to mention gay assimilation at large. I was raised by radical lefty parents who didn’t get married because they didn’t believe in it, and I suspect I’ll follow in their footsteps. Beyond marriage’s roots in patriarchy and its ties to the state, I’ve come to agree with my parents that a relationship is not something you sign a contract for.

I’m also, however, a sap, and a realist about the fact that human emotion doesn’t always align with radical political theory. I cried when Edie Windsor won her case against the Defense of Marriage Act, not so much because I thought her inability to marry her partner was the pinnacle of oppression, but because the wounds caused by decades of being told that you’re sick and inhuman are devastating—and winning in the same court that has thrown you out is one small kind of healing.

Bride Pride’s organizers, Roux Bed & Breakfast owners Allison Baldwin and Ilene Mitnick, planned a full menu of events for the fifty-three couples getting married or renewing their vows: a bridal shower the day before, mimosas and breakfast the morning of the ceremony, and finally, a trolley ride down Commercial Street to a champagne reception. The wedding was borne out of Baldwin and Mitnick’s plans to renew their own vows; hoping to bring more women to Provincetown, they decided to open their ceremony up to everyone.

I arrived in Provincetown on Friday, the day before the wedding, and checked in at the Seaglass Inn & Spa, a hotel on a hill that practically glowed in the early afternoon sun. The inn, one of Bride Pride’s sponsors, was hosting the bridal shower, so I followed the sound of voices to the party in the garden.

It was a perfect fall day, so warm that I regretted wearing a sweater. Tables arranged around a heated pool were set with hors d’oeuvres, alcoholic and non-alcoholic punch, and vanilla and chocolate cupcakes with rainbow frosting. A well-kept lawn surrounded the pool, and it was here that I encountered a crowd of about forty women, who were all in the process of taping yellow balloons to their butts.

I was more than a little sheepish as I walked up, holding my notebook in one hand, shielding my eyes from the sun with the other. I had no bride, no date, and no reason to be here other than to document this incredibly personal event in the lives of strangers. But almost no one noticed me. Those who did smiled welcomingly. A woman with a Southern accent called out, “Is my balloon okay?” Someone reassured her that it was.

The emcee, a handsome butch with a pompadour, explained the rules of the game, which turned out to be a balloon-humping relay race: the women form two lines. The first woman in each line runs up to a lawn chair and holds onto it. The next woman runs up and humps the hell out of her until the yellow balloon taped to her butt pops. Then the humper becomes the humpee, and the next woman runs up and attempts to pop her balloon. And so on, and so on.

The game began and I found myself in the middle of the most gleeful party I could remember attending. Women grabbed each other by the shoulders, the hips, anything they could hold onto. Short women stood on their toes to hump higher. Women being humped, impatient at the ineffectiveness of their humper and eager to help, thrust their butts backwards. Everyone was laughing. I couldn’t help myself—I was too. It felt easy to forget that all of these women, having come here in units of two for a mass wedding, were strangers to each other.

At the end of the game, two middle-aged women were left pumping away hopelessly at each other. “Remember the night you met!” the emcee instructed. “Show her you can still do it!” The whole crowd started to cheer them on: “Pop that balloon! Pop that balloon!” The women kept trying, kept humping. It was a theoretically vulnerable moment, but there wasn’t a shred of embarrassment on either of their faces—just laughter. Finally, after what felt like a year, someone took pity on them and popped the balloon with a car key. The garden erupted in applause.

The wedding at Roux Bed & Breakfast was set to begin at 11 a.m. on Saturday, but the brides had been invited for a pre-ceremony breakfast with mimosas and photos an hour beforehand. I arrived at 10:15, passing between tall, neatly trimmed hedges to find a white Victorian house, restored to the letter and gleaming under a cloudless blue sky. A few guests milled about on the freshly cut lawn, toting cameras and chatting. If it weren’t for the Bride Pride flag waving from the porch, this could have been the pre-wedding party for a straight New England wedding—for just one couple, of course.

The breakfast was around back, so I walked through Roux’s brightly painted rooms—marigold entrance hall, peacock dining room, royal purple kitchen—and opened a screen door into a long backyard bathed in sunlight. Bamboo fences lined the garden, and flowerpots full of roses hung from the posts. Buffet tables were set with trays of chocolate truffles, crudités, fruit, mimosas. At the far end of the yard a professional photographer had set up a mini-studio.

There were women everywhere: women in white button-downs, white pants, and matching rainbow bowties; women in lavish wedding dresses with partners holding their trains; butches in black dress shirts and matching embroidered vests; butches in grey suits with purple and yellow ties; women in long cardigans and glasses; women in tiaras and black cocktail dresses; women wearing all-white denim and aviator sunglasses; and quite a few women in flashy, chic pantsuits.

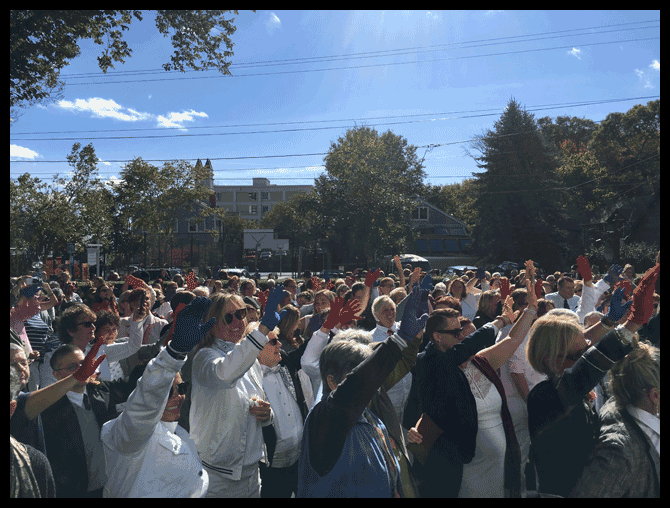

After breakfast, the ceremony began, and all 106 of these women joined hands and stared into each other’s eyes on Roux’s front lawn. Hundreds of their friends and family crowded in, spilling onto the sidewalks, the driveway. A drone overhead was recording the official wedding video. Then there was me: standing in a flowerbed where I found a few feet of unoccupied space, trying to write it all down without crushing the hydrangeas.

I had been expecting to feel moved by this wedding. A few years ago, a woman in a car called me a dyke and told me she hoped I’d die; I’m guessing that’s a rite I share, in some form, with every person who was on that lawn. As the women exchanged vows, I found myself thinking not about marriage but about shared history: queer people kicked out by their families, forced into conversion therapy. Thousands of lovers and friends turned away from “family-only” hospital room visiting hours, millions of glass bottles thrown at bowling alleys and on street corners. And we’re not just defined by tragedy, either: I was thinking of queer sex, of drag, of learning to love ourselves in the face of a culture that violently hates us. I was thinking of 4,000 queers making out on the National Mall in 1987, and 106 women kissing now—two giant fuck-yous to anyone who has ever called any of us disgusting.

Tin Pan Alley, a local bar down the street from Roux, hosted the champagne toast after the wedding. I made my way around the crowded room, listening to people’s stories. Everyone had one: the couple from Ireland who met playing soccer and had been together for thirty-six years. The couple who had been married five times, each time seeking—and failing to find—legal recognition. After their wedding in Oregon was ruled invalid by the state Supreme Court, they received a check in the mail, refunding the cost of their license, and a letter informing them that they were not married.

I spotted a couple in matching New Balances sitting in the window. Their names were Sharon and Sue and they had been together thirty years. They talked to me with a guardedness that had become familiar. (Another older couple, earlier this weekend, had made me promise not to identify them. They’re out, they said—“it’s just not the kind of thing you put on paper.”) Sharon and Sue were from Florida. They both worked in the school system. For decades they hid their relationship: they sat through meetings full of homophobic jokes, concealed the fact that they lived together, went to Christmas parties without each other, listened to their coworkers talk about their spouses and pretended not to have their own.

They’d been together for years when Sharon’s supervisor called her into his office and asked her point blank if she was gay. She told him she wasn’t.

“You have to understand,” Sue said to me, like she was talking to a child too young to remember a war. “We would’ve been fired.”

All weekend, I’d been asking couples, “Why marriage?” A lot of women talked about fighting so long for this right. One woman told me, “I always grew up thinking I would never be able to get married. It’s validation of us being part of humanity.”

All of which made sense. But the most common answer I heard was security. Legal reasons. When I asked Sharon and Sue, they didn’t hesitate: “We need some protection.”

They reminded me that Florida’s governor is no friend of gay marriage—that in fact, if he’d had his way, the state’s ban on weddings like theirs never would have been lifted. I imagined a thin red thread stretching all the way from Sharon’s supervisor so many years ago to the Florida Governor’s Mansion in 2016. In January, that thread extended north to the White House, where the 45th president began packing his cabinet with men who want to make America white, straight, and Christian again. Already the Trump administration has revoked federal guidelines ensuring transgender students’ right to use the bathroom matching their gender identity. “Protection” has become an open question.

As I left the bar, I saw a woman with a guitar beginning to play. I stopped to listen by the door. It was a sweet, simple song—the chorus some variation of “I love you, I love you / like never before.” The couple from Ireland was the first to start dancing. The five-times-married couple joined in. They kissed each other’s hands. “Could this be your first dance?” the woman with the guitar asked, smiling.

And of course, it was not. Not at all.