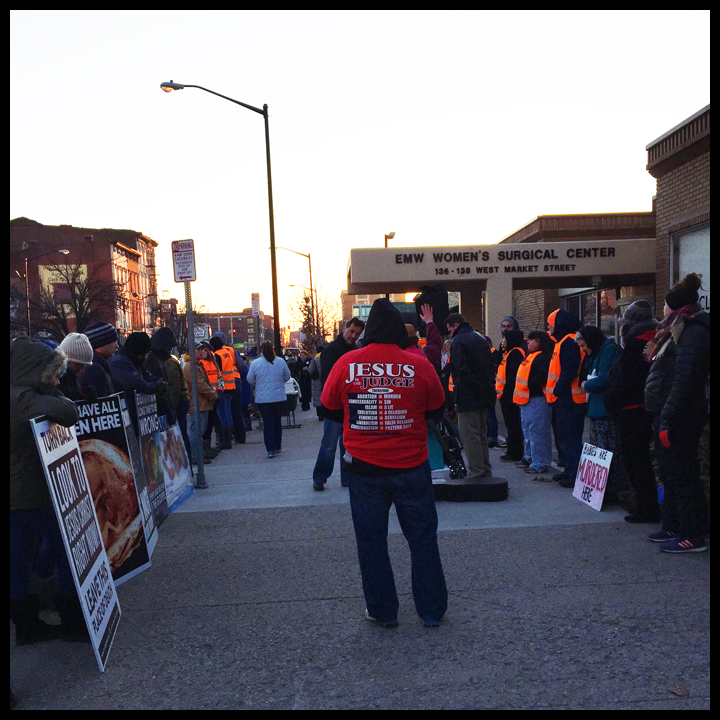

At dawn on a frigid Saturday morning in February, I stood outside the EMW Women’s Surgical Center in downtown Louisville, Kentucky, in the middle of seventy antiabortion protesters. The picketers—many of them middle-aged, white, and male—were energized. They lined the block, shouting “You don’t have to do this!” and aggressively shaking signs that read turn back. They harassed the clinic’s two dozen volunteer escorts, who were clearly marked out by their neon orange vests. Still, the escorts held their positions on the sidewalk and in front of EMW’s mirrored double doors, remaining stone-faced as they ushered exhausted patients through the loud crowd and into the clinic.

I saw an orange blur rush past me. Four escorts had run over to a young woman who was hurrying up the sidewalk in sweatpants and a black hoodie. They huddled around her. One of them, a tall African-American man named Keith, leaned in and asked if she wanted them to walk with her.

She nodded.

She held on to Keith’s arm. A wave of protesters quickly descended on them: “Don’t do this, you can change your mind!” one woman shrieked. A group of teenage boys thrust in the woman’s face homemade posters that read babies are murdered here in smeared red letters, and a couple of older men shook signs with photoshopped images of bloody, dismembered babies in the palm of a woman’s hand, beneath the word choice. One woman prayed loudly next to a tiny casket, its lid covered with oversize plastic fetuses.

The woman in the hoodie clutched her head, tears streaming down her cheeks. The escorts pushed her through a group of protesters on the sidewalk and past a painted white property line, along which ten more escorts had formed a barricade. A male protester, standing just a few feet away from the door, stepped up to a mounted microphone and screamed, “You don’t have to kill your baby! You don’t have to be a murderer!”

The wall of escorts briefly opened up, and the woman stepped inside EMW, the last place in Kentucky where she could get an abortion.

[1] In states with less restrictive regulations, such as California, the procedure can be legally obtained up to twenty-six weeks into a pregnancy. Seven states and the District of Columbia don’t have any term restrictions.

Kentucky is one of six states—along with Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, and West Virginia—that today has only one abortion provider. In the years after the Supreme Court issued its ruling on Roe v. Wade, in 1973, seventeen providers opened up in the state, including EMW. But since then, the state legislature has passed dozens of laws making abortions increasingly inaccessible. Facilities were required to have transfer agreements with nearby hospitals; public hospitals and health clinics were banned from using state funds for abortions (except in cases of life endangerment, rape, or incest); women were required to receive state-directed counseling and then wait twenty-four hours before having the procedure; and health insurance providers stopped covering it for state employees. By the late Nineties, EMW was operating Kentucky’s last two clinics, the Louisville location and a second in Lexington, which was open only part-time and provided the procedure up to twelve weeks.[1]

In February 2016, as one of his first actions upon taking office, Governor Matt Bevin sued Planned Parenthood—which had recently begun providing abortion services in Kentucky—and EMW’s Lexington clinic on the grounds that they did not have the proper licenses. According to the director of the EMW clinic in Louisville, the state’s inspector general soon after denied the Lexington clinic its license, and the landlord, whom the organization had rented from since 1989, refused to renew the lease. This January, just seven days after Donald Trump was inaugurated, the EMW clinic in Lexington closed.

As the legislative crackdowns have worsened, so too has the situation on the street. “The protesters have absolutely gotten more aggressive,” Meg Stern, the support-fund director for the Kentucky Health Justice Network, told me. Stern began escorting in 1999, when she was eighteen. Back then, she said, protesters usually just prayed and held signs, but they’ve been emboldened, and their tactics have escalated to include physical force; it’s not uncommon now for them to push, shove, chase, and stalk the patients and escorts. “The day after the inauguration, protesters were out celebrating,” Stern recalled. “Someone said to my face it was a ‘great day for the babies.’”

After the woman in the hoodie was safely inside the clinic, Keith walked back to the street corner. Keith, a theater teacher and comedian who volunteered two or three days a week, was one of about a hundred people who signed up after the election to escort in Louisville. “This is a big step out of ‘I’m going to vote for the right person’ or be liberal when it comes to this, or talk about the right issues,” he said. “This is a very public stand.”

While we chatted, a protester approached Keith and shoved a pamphlet about the sins of abortion in his face, comparing it to slavery and calling it black genocide. (This is a common conspiracy theory among antiabortion activists because the abortion rate is higher among black women than it is among white women. People of color tend to be targeted more than their white counterparts by protesters, who often use racially charged language to try to shame them.) His hot breath clouded the frigid air. Keith turned away, watching for cars.

Over the next forty-five minutes, seven more women arrived at EMW. Each time, the escorts appeared at her side, guiding her through the crowd to the front door. By nine o’clock, all of the patients for the day were safely inside, prepping for their procedures.

[2] The Kentucky chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union is contesting the law on the grounds that requiring doctors to show and describe ultrasound images to a woman violates First Amendment rights.

Meanwhile, outside, the protesters chatted, patting one another on the back, warming their hands, and exchanging hugs while sipping the last of their coffee. Many would return the next weekend, to show their support for the state’s crusade against abortions—which has shown no signs of slowing down: Earlier this year, antiabortion bills were passed that ban abortions after twenty weeks, without exceptions for victims of rape or incest, and require doctors to show patients ultrasounds.[2] And in March, Bevin’s administration moved to shut down EMW’s Louisville clinic. The A.C.L.U. sued the state on the clinic’s behalf. The trial is expected to begin in September.

With Bevin pushing one of the country’s most aggressive antiabortion agendas, EMW has drawn hundreds of hardcore activists from across the United States. In May, ten people were arrested at a protest led by Operation Save America, a Texas-based, fundamentalist antiabortion group, for blocking entry to EMW. In preparation for the group’s annual conference, which was held last week in Louisville, a federal judge issued an order creating a temporary buffer zone in front of the clinic. The protesters say that they see an unparalleled opportunity: Kentucky presents their best chance of becoming the first state in the country without an abortion provider.

Before I left that morning, an older man told me that a group of them was heading to a protest at a hospital where, he had heard, there was an ob-gyn who “kills babies,” though he admitted that he had no idea who the doctor was or where he worked. The man working the sound system played soft Christian rock and held a wailing baby doll to the microphone. Its cries echoed around the block.

Keith and I walked together for a few blocks before he headed home. “I know it’s going to happen that someone who disagrees with a woman’s right to have an abortion may recognize me, and it may cost me a job,” he told me. “And I’m all right with that. I realize I’m exactly where I’m supposed to be when I’m standing there in an orange vest.”