A Private War

Life during wartime is more complicated than easily digestible, Hollywood heroism

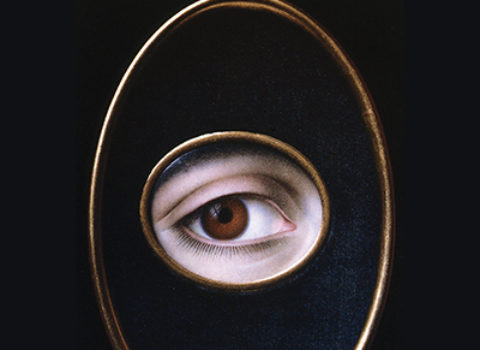

Still from A Private War

When young women come to me and say, “I want to be a war reporter!” after seeing Hollywood films that glamorize the job, I always tell them gently to consider the life that it entails. Perhaps the mantra that first-wave feminists gave us is not true after all: you cannot have it all. Or at least not without dark consequences.

In 2012, while working on a story about war criminals in Belgrade, Serbia, I got a devastating early morning phone call: my colleague and friend Marie Colvin was dead, killed by Bashar al-Assad’s bombs in Homs, Syria. Her roller-coaster life is captured in a new film, A Private War, currently in theaters.

The director of A Private War, Matt Heineman, won accolades for his brilliant documentaries on the drug war (Cartel Land, 2015) and the Islamic State (City of Ghosts, 2017). He struggled, as did the actors, to make the film truly authentic. But because it is not a biopic (Heineman resists the term) and some characters are composites, the movie is confusing to those of us who know the real story. There were no good guys at the Sunday Times, where Colvin worked, who cared for her well-being. There were instead editors who wanted scoops at the expense of the safety of their reporters. Colvin had many friends in London, but none of them were similar to the Bridget Jones–style girlfriend character (portrayed by Nikki Amuka-Bird) in the film. Her last boyfriend was not a caring and loving Stanley Tucci but rather a man who gave her immense heartache and distress. There were no “heads on sticks” in Bosnia, as the character meant to be Colvin’s first husband, Patrick Bishop, says in one of the opening scenes (heads were on sticks in Chechnya). Colvin’s second husband, Juan Carlos Gumucio, is erased from the script altogether, though he played an important role in her life.

A more accurate and moving film about female war reporters, Bearing Witness, was co-directed by Barbara Kopple, the Academy Award–winning documentarian, who contacted me in the fall of 2002. Since I began reporting from conflict zones in the early 1990s, I had been asked dozens of times whether women reported war differently from men. “No,” I would bristle, annoyed by the question. I did not confine myself to reporting from hospitals and orphanages. I went to the front lines with soldiers and embedded with rebel armies. I lived for months in the field or the bush; I did not wash; I carried the dead and wounded out of trenches. I did everything my male colleagues did, and tried to mirror their emotions. At least I thought I did.

The documentary was meant to be a granular reflection of women in a highly macho world. It focused on me and three other women, one of them Marie Colvin. A Private War does depict Colvin’s tortured life, but Kopple’s film captured the real Marie Colvin: without Hollywood glamour, props, or wardrobe. Although Rosamunde Pike’s performance in the new film is brilliant, I preferred the gritty reality of Kopple’s painful but real documentary about the lives of women who chose to be war reporters.

Despite Kopple’s renown—she won her Oscar for Harlan County, USA in 1976—I had misgivings about being the subject of a documentary, because at the time I was questioning the choices I had made about my profession. I believed in bearing witness (the title of Kopple’s film) to atrocities, and I was motivated by a strong sense of justice. But I wanted, more than anything, to have a family. I yearned for the stability and balance I didn’t have as a war correspondent. After two decades in war zones, witnessing the siege of Sarajevo, the fall of Grozny to Russian forces, the genocides in Srebrenica and Rwanda, the child soldiers who tried to kill me in Liberia and Sierra Leone, I was burnt out.

I wanted a kitchen where I could cook Thanksgiving dinners. I wanted to tell friends to come around for supper and to be there, without leaving a note on the door that I had been called away unexpectedly to the Congo or East Timor.

When I started reporting, PTSD was not common among war reporters, but after a particularly grueling mission in Bosnia, I was contacted by a Canadian psychiatrist, Dr. Anthony Feinstein. He used me and some of my colleagues as subjects to conduct a three-year study on the effect of trauma on frontline reporters. His remarkable findings were published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, and later in a book, Dangerous Lives, which became a road map for how news organizations could protect their reporters

When Feinstein called me into his office in London for my final consultation, he told me I did not suffer from PTSD, despite the terrifying hallucinations I had post–Sierra Leone of amputated people everywhere. He believed I had a strong core of resilience. I mistakenly took that as a benediction, so I pushed myself even harder, farther down even lonelier roads and more perilous assignments, closer to death. It did not help that the news organization I worked for at the time encouraged me to perform more daring exploits in order to get a big story.

I experienced a kidnapping; a mock execution in Kosovo; too many near rapes to count; a drunk soldier pointing an AK-47 (safety off) at my heart in the Ivory Coast as I tried to drag a wounded man to a hospital; death threats from Foday Sankoh’s government in Sierra Leone for stealing documents related to blood diamonds; and bombardments so fierce in Grozny that I thought my eardrums would rupture. My nerves certainly suffered.

I’d come back from assignments to my London flat and try to recover, to piece my life back together. Many of my colleagues were completely devastated by what they had seen. The level of alcoholism, divorce, drug abuse, breakups, misery, and sorrow once we left the front line was astonishing. There was a period in my life when I found it intolerable to go to parties and hear what I perceived to be the banalities of ordinary life. My colleagues and I rejected the traditional world, and we were paying the price for it.

One night, Juan Carlos, Colvin’s second husband, and I were partying late. JC, as we called him, was the last to go. I walked him to the door. He took my hand. “Goodbye,” he said. “I won’t see you for some time.”

“But I’m seeing you in a few weeks,” I replied, recalling a gathering coming up in the not-so-distant future.

He shook his head, smiled, and said, “No, you won’t. It’s time.”

I suddenly realized what he meant: suicide. I ran down the stairs after him. “Don’t do that!” I pleaded. “It’s so much darker down there.”

I was in Somalia a few months later, working on a story for The New York Times Magazine on the Shabab when I got a call on my satellite phone. JC had shot himself back home in Bolivia. I sat on the rooftop, the sound of gunfire ringing through Mogadishu, and wept for my beautiful friend. Colvin later told me, “He saw too much.”

I also wept for myself and what I was missing, and so I made a hard choice as I watched the statue of Saddam falling in Firdos Square in Baghdad a few years later: I vowed I would have a normal life. I was engaged to be married to another war reporter, whom I had met during the siege of Sarajevo. We wanted to have a child, to ease the darkness of our lives, to have redemption.

By the time Koppel’s documentary crew came to film our wedding in the French Alps, my husband’s ancestral home, I was pregnant. My happiness dissolved when, dressing for my wedding, I caught sight of the news: the UN headquarters in Baghdad, the Canal Hotel, had been hit by a car bomb. My husband and I watched the TV, horrified—but also conflicted about the fact that we were not there, in the midst of it.

My employer, the Times of London, was not thrilled with my new role.

“I’ve got a war reporter who can’t go to war!” thundered the then foreign editor, a father of five. “How am I going to cover this war?” When I suggested he use someone else, he fumed, “I can’t send inexperienced people! What you are good at is getting into places other people can’t go!” I suddenly realized he thought of me as cannon fodder.

He forced me to go back to Iraq while I was still breastfeeding, stating that it was in my contract. I sobbed on the plane, with a picture of my infant tucked in my pocket. I sobbed in my Baghdad office when I had to pump breast milk and throw it down the drain. I heard a male colleague say triumphantly on the satellite phone, “She had a baby and lost her nerve!” They sent me to Sadr City anyway, at a particularly dangerous time, my body still recovering from a high-risk pregnancy and six months of bed rest.

But that male colleague was right: I had changed. I always found it hard to witness the extreme suffering of children and innocents. The first time I saw a child shot in the abdomen, in Central Bosnia, screaming in agony with no painkillers, I threw up. I tried to be tougher, but I never developed the thick skin I needed. Motherhood made it nearly impossible to watch children suffer, as I saw in the later wars I reported, in Syria and Yemen. I would decompress by coming home and playing with my son, and becoming the most clichéd 1950s housewife I could imagine: I even baked cakes and wore an apron.

I tried, but I’m not sure I mastered this schizophrenic existence. Earlier this week, I went to a parent-teacher meeting at my son’s school. My husband, Bruno, who bravely battled his own PTSD demons and conquered them, and I separated long ago but continued to co-parent with a profound desire to give our son stability and love. When Bruno was shot by a sniper in Libya during the fall of Qaddafi, I broke the news to my son gently, realizing how unnatural this was. His dad was evacuated from Tripoli, recovered, and was fine. Our boy grew and flourished.

But this week, one of his teachers told me about a paper he submitted. When asked what the students feared the most, most of the boys in his ninth-grade class wrote about how hard it was to talk to girls. But Luca wrote, “I am afraid my mother will get her head chopped off by a sword in Iraq.” And it suddenly occurred to me, with shame, that all of my bravado about being the same as the male reporters was not accurate. Women, when they choose to be mothers, have to make a choice, and I was not entirely honest about mine: this lifestyle was hurting those who loved me.

Marie Colvin did not have children; neither did Martha Gellhorn, my role model and Hemingway’s third wife. Very few of my female colleagues did. I did not have many role models, and so I winged it the best I could. I made mistakes—the early Iraq trip when I should have stood firm and said no, the journeys away from home when I should have been there—but I am proud of the work my colleagues and I do, especially the evidence that we supply to war-crime tribunals. I also know that my work casts a shadow on the people dearest to me. My son once said to me, “I never know when you go away if you will come back again.” That broke my heart, even though I know he is proud of the work his parents do.

Kopple’s film shows the darkness of Marie Colvin’s PTSD, alcoholism, and struggles with combining real-world responsibilities with her extraordinary career. Her sister, the attorney Cat Colvin, once described how Marie would jet back from war zones to be at her close-knit Irish Catholic family’s holiday dinner table on Long Island. Her working life—its minefields, mortars, and snipers—seemed a million miles away from suburban Long Island, with her nieces and nephews running around and a hearty meal on the table. That, too, was part of her struggle—the effort required to balance her life.

But I respect A Private War because I applaud the depiction of Colvin’s courage and her legacy. I just don’t want young women to watch it and think that being a war reporter is glamorous. It is not. If they want to know the gritty and unpleasant reality—the heartache, the miscarriages, the alcohol, and the emotional hangovers—they should take a look at Barbara Kopple’s 2004 documentary as well.