In those days the world teemed, the people multiplied, the world bellowed like a wild bull, and the great god was aroused by the clamour. Enlil heard the clamour and he said to the gods in council, “The uproar of mankind is intolerable and sleep is no longer possible by reason of the babel.” So the gods agreed to exterminate mankind.

—The Epic of Gilgamesh

In this way begin the earliest written version of the Great Flood myth, which reappears in altered form more than a thousand years later as the biblical story of Noah and the Ark. The Sumerian origins of the Gilgamesh epic may help to explain why the gods are so incensed. Sumeria is generally considered the world’s first civilization; that is, the first place where human beings create a distinctly urban society. It seems that by at least the third millennium B.C.E. the world has begun to grow noisy, at least for those living in the mud-brick cities of the Fertile Crescent, the first people on earth to hear the shake, rattle, and roll of turning wheels. The city that never sleeps is born here, memorialized in a story about angry gods who cannot sleep either. The twenty-first-century tenant who some nights would like to strangle his noisy neighbor lives no more than a story up from some literate Mesopotamian who apparently imagined drowning his.

Human noise is political from its inception, not only because it emerges with the polis—that artificial forest where the tree that falls always makes a sound—but also because it lends itself so well to political conflict. Noise is both an objective and a subjective phenomenon: it comprises both common and uncommon ground. On the one hand, a decibel is a decibel is a decibel. The fact that the human ear can endure about two continuous hours of a power drill but only thirty minutes of a typical video arcade before sustaining permanent hearing loss and the related fact that eighty-year-old Sudanese villagers hear better than thirty-year-old Americans are just that: facts. On the other hand, the reasons why an airport will affect its neighbors in different ways, leaving some depressed or hypertensive and others relatively unfazed, are as variable and invisible as sound itself. Even the gods who confer with Enlil are not of the same party on the noise issue. At least one of them objects to eliminating human commotion at its source, and consequently a chosen few are able to step blinking from the ark into a temporarily quieter world.

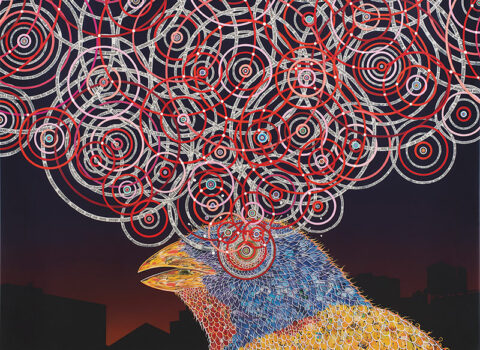

By the time we get to the monotheistic universe of Genesis, the flooding of the earth is presented as the result of God’s moral indignation. Wickedness, not noisiness, is what starts the rain. Yet I can think of few symbols more suited to wickedness than noise, usually defined as “unwanted sound”—like defining an assault as “unwanted attention.” Loud noise hates nature and nurture alike. Certain species of birds fail to learn their mating songs, and therefore to reproduce, in noisy environments; as early as 1975, researcher Arline Bronzaft found that children on the train-track side of a New York public school were lagging a year behind their classmates on the other side of the building in learning to read. Even relatively low levels of noise can interfere with conversation (at 55 to 60 decibels); the price of making ourselves heard is a loss of nuance, inflection, vocal stamina—in every sense a “loss of voice.” Noise has been linked to heart disease, high blood pressure, low birth weight, gastrointestinal disorders, headaches, fatigue, insomnia—in short, to nearly every known by-product of stress. (Anti-stress medications are actually tested by exposing experimental subjects to loud sounds.) Noise deafens us, aurally and there is strong evidence to suggest-morally as well. People subjected to high levels of noise are less likely to assist strangers in difficulty, less likely to recommend raises for workers, more likely to administer electric shocks to other human subjects.

Noise speaks danger; it both threatens and invites aggression. It triggers the physiological chemistry of the “fight-or-flight” response. Before we were even human, noise signaled the approach of the carnivore, of lightning and lava. More recently it became the alarm of invasion, first of the barbarian outside the gates and increasingly of the barbarian within. The audio-terrorist turns into decibels the dynamics of every relationship based on unrequited power: My noise can penetrate your quiet, but your quiet can never penetrate my noise. “My noise is my right” means “Your ear is my hole.”

To this little rant of mine the Roman philosopher Seneca offers a censorious tut-tut. “I cannot for the life of me see that quiet is as necessary to a person who has shut himself away to do some studying as it is usually thought to be. Here am I with a babel of noise going on all about me.” He is living over a bathhouse; the noises rising from downstairs include all manner of “grunting,” “hissing,” and “pummeling,” as well as “the hair remover, continually giving vent to his shrill and penetrating cry in order to advertise his presence . . .” Seneca boasts that he takes “no more notice [of] all this roar than . . . of waves or falling water.” To be distracted by noise, he claims, is to succumb to one’s own inner disquiet. I believe him, somewhat. But let us credit Seneca’s stoicism for enduring the 50 decibels of a very loud hiss and estimate the cry of the hair remover at, say, 65 decibels, 75 if he has a very loud voice. Today Seneca would be living over a gym where the amplified music might be cranked to 100 decibels in order to produce the adrenaline rush that keeps the iron pumping. (And for every increase of 10 decibels, the volume of sound doubles.) If Seneca were one of the quarter million New Yorkers living within 100 yards of an elevated train track, he might be able to test his fortitude with a screech of 115 decibels, as measured at the front step of his apartment building. At these levels philosophical detachment is almost a joke. What do you call a stoic who lives near the el? Deaf.

City ordinances aimed at noise date roughly from Seneca’s time; Caesar is said to have banned nighttime chariot riding from the streets of Rome. Fiorello La Guardia tried to outlaw organ grinders; New Yorkers, to their lasting credit, told him to back off. Noise not only confers power; it is silenced by power. As anti-noise activists are quick to point out, the traditional noise ordinance has usually been aimed at and enforced against the individual. The kid with the boom box is one thing; the Federal Aviation Administration, which virtually regulates itself, is quite another. Indeed, the most effective noise ordinances I’ve found were gag agreements imposed as “compromises” on the critics of noise-making companies: in exchange for ninety “mufflered days” at the auto racetrack, your citizens’ group will hereby withdraw its litigation; in exchange for an offer to purchase your soon-to-be-worthless house, you agree not to oppose the permit application of our soon-to-be-opened quarry. Ronald Reagan’s shutting down of the Office of Noise Abatement and Control in 1982 and the failure of any president since to reopen it may go down as the most effective “noise ordinance” in American history. At the time there were 1,100 local and state programs monitoring noise; now there are about 20. Has anybody ever said, “Turn that damn thing off!” with greater success? One should always be wary, then, of equating quiet and silence. In the politics of quiet and noise, silence sides with the winner.

“I shall shortly be moving elsewhere,” Seneca writes at the end of his essay on noise. “Why should I need to suffer the torture any longer than I want to . . .” Then, as now, stoic resignation was good, but an aggressive realtor was even better. From the first wheel that rattled through the streets of Sumer, the story of noise has always been tied to the story of human mobility—not least of all in America, arguably the world’s first nomadic civilization. If there are any fundamental principles to the relationship between noise and mobility, I can discern at least two. The first and simplest goes like this: People move to escape noise, and by moving they always find it.

Forty years ago the poet Galway Kinnell came to northeastern Vermont looking for “a house with a view at the end of a long dirt road” that he could buy for $800. Outside the somewhat haggard village of Sheffield he found what he was looking for, or the closest approximation: a fallen-in farmhouse with broken windows and missing doors, which during Kinnell’s earliest visits he shared with a pair of porcupines and a weasel. “Living out of reach of human activity,” close to wild animals but within hearing of “the accent and pleasure of words, the love of getting things right” that Kinnell says “was more true of old-time Vermonters than any other people I know,” the poet also found the materials for his work. And he found quiet, measurably more quiet on a summer evening than the sound of a human whisper, enough to live what he refers to as “an objectification . . . of my inner life.” Of course, the danger in objectifying your inner life is that someone might drive a bulldozer over your heart.

The bulldozer arrived two years ago to clear-cut a nearby tract of land for the site of a South African-owned granite quarry. For many in town the appearance of the South Africans in Sheffield held a promise of jobs, tax revenues, and royalties, perhaps a less obscure place on the map; Kinnell had a different view. Fearful of what the newcomers might do to the landscape and suspicious of what they might have done to other landscapes and villages beforehand, he and a handful of like-minded neighbors opposed the quarry company’s application for an environmental permit. Kinnell has already begun to hear the noise of blasting and heavy equipment in the distance and fears that he will soon see giant grout piles rising where he now sees nothing but trees and the chimney smoke of a few isolated neighbors.

About a year ago I began to follow the permitting process, which included a contested noise demonstration and a hilarious soggy trek through cedar swamp with lawyers wearing inappropriate shoes. The process held a special fascination for me, in part because Kinnell had seemed to be living the same dream that brought me to live in a town just one ridge over from his and was now living the nightmare that always dogs such a dream. I, too, count moose and bear among my nearest neighbors. I can see virtually every star one is able to see in the northern hemisphere. In the stillest hours of the early morning, Adam in his Garden has little over me. “It’s so quiet here,” say my guests from New Jersey. “So peaceful.”

And so vulnerable. Quiet, after all, is the most assailable form of wealth. The same thief can forever be stealing it. It can grow back in a moment’s respite, like the liver of Prometheus, only to be devoured by the screaming eagles once again. To tell a truth I seldom admit, sometimes I feel most at peace when I am seated on the porch of my in-laws’ house in a blue-collar town in New Jersey, watching the kids play on the sidewalk and listening to the manhole cover tap amiably under the frequent traffic. Everything is settled there: I mean all the land and all the possibilities that haunt you when you’re tempted to believe that your world extends as far as you can see and hear.

All of this is to locate the psychological place from which I began my exploration of quiet and noise. Like most quests, it began with “a passing sight,” a disturbing image that one cannot easily suppress. Mine was the sight of Galway Kinnell’s face when an environmental board member asked him, somewhere on the dirt road that led to the quarry, “Now, where is your house, Mr. Kinnell?” He turned and pointed toward a hill, several miles across an open field, with an obliging smile and the eyes of someone who has realized for the first time that he can die.

Again and again, the people I found in the forefront of some anti-noise campaign were individuals who had moved from a noisier place to a quieter, only to have that quieter place grow loud. When Jane Moore came to Jerome, Arizona, some twenty-eight years ago, it was practically a ghost town. Formerly the site of a booming copper mine and home to 15,000 people, it was then a cluster of mostly abandoned buildings on either side of a desert highway. Moore was among the artists and squatters who began taking up residence next door to the few locals who had managed somehow to hang on. It was a place of steep canyons and weird acoustics: a clack of pool balls or a wind chime’s jangle sounding in unexpected comers like the traces of restless spirits. For Moore, who had grown up next to a freight switching yard in Chicago, five miles away from O’Hare Airport, this was the place of quiet ambience she had always been searching for. She may find herself searching again. There are presently about 350 adults in Jerome, including three police officers. On some weekends as many as 500 motorcycles pass through to town, many sporting “modified” exhaust pipes that together with the terrain amplify the thunder of their descent through the canyon. A favorite stop is a rock-and-roll bar in town called The Spirit Room. Vice Mayor Moore and her associates in town government are attempting to pass a noise ordinance; the Modified Motorcycle Association of Arizona has promised that any such law will not go unchallenged. Bikers made the same point by driving into town one weekend and filling it with the modified sound of their presence.

There’s an implicit cultural symbolism in conflicts such as this, none more pronounced than what I found in the ongoing feud between the New Hampshire International Speedway in the working-class town of Louden and the residents of scenic Canterbury, home to the “most intact and authentic of all Shaker villages” in America. The countryside and much of the architecture around Canterbury are about as arcadian and colonial as one could imagine. Some 1,800 of the original 3,000-acre Shaker holdings, roughly 700 owned by the Shaker museum itself and the rest owned privately, are all under conservation easement. The tranquillity of the place would seem to be “secured,” established, unassailable. But on major race weekends—as opposed to ordinary race weekends, which are virtually every weekend from April to October—the noise of 450-horsepower stock cars in neighboring Louden can reach the decibel level of jet planes. Standing in the front yard of a Canterbury residence, one sound expert measured noise levels as high as 85 decibels, roughly the same level as a lawn mower heard from six feet—this coming from a source half a mile away. For Hillary Nelson, who moved from New York to Canterbury with her husband, such noise is an atrack on her quality of life. To many of the people in Louden, who have received tax revenues, a new ball field, a new fire engine, and $50,000 a year in college scholarships from the racetrack, noise is what you pay for quality of life.

In both Louden and Jerome, the source of the offending noise grew from a smaller, preexisting source of tolerable noise. As long as anyone can remember, there has been a biker bar in Jerome and a racetrack in Louden. What is more, by all accounts the patrons of both of these earlier establishments, though fewer, were wilder than the people who frequent them now. As the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse’s Les Blomberg explained to me, one of the most frequent arguments made against those bothered by noise is that the offending noise source “was always there.” The Sheffield quarry is being touted as a “reopening” of a pick-and-shovel operation that once extracted granite on the site. The Amcast plant in Cedarburg, Wisconsin, a large foundry that also has been at the center of a noise dispute with some of its neighbors, expanded from a small munitions plant during the Second World War to a major supplier of castings for the automobile industry. In each of these cases the disingenuous argument of “prior occupancy” is accompanied by avowals and sometimes even by hard evidence that the noisy party is trying, somewhat, to be “a good neighbor.” Amcast, for instance, spent an estimated $400,000 in an attempt to make its foundry quieter, and seems to have succeeded. Even his critics credit racetrack-owner Bob Bahre with running an orderly operation that caters to a “family” clientele. Likewise, the owner of The Spirit Room bar is known to his patrons and to those who’d just as soon see his patrons spirited away for urging bikers not to rev their engines in town. Nevertheless, the thought of a 90,000-seat NASCAR track being “a good neighbor” to a rural village, or 500 motorcyclists becoming good neighbors to a town of 400, is something like the thought of King Kong being a good lover to Fay Wray. It may be sincere, it may even be noble, but if you’re the one gripped in the big hairy paw it can only feel obscene.

The subject of noise and scale is of particular interest given the value we now place on cultural and biological “diversity.” The soundscape provides both an example of diversity and an instructive analogy to other domains. A smaller sound can coexist with a number of other smaller sounds, but even a number of smaller sounds cannot coexist with one big noise. Never mind the forest—if a baby falls during a rock concert, does it make a sound? Different forms of the same question can be applied to species, languages, and ways of life. Those who dismiss the noise issue as “merely aesthetic” are, of course, ignoring the well-documented medical and psychological effects of noise. They are also forgetting that, in the context of relationships, aesthetics can become ethics.

The other thing that interests me about noise disputes is the way in which class conflict informs them, or seems to inform them. Of course it was no surprise to learn that a poorer life is frequently a noisier one, that those with low incomes are more likely to suffer from noise than the affluent, more likely to work next to the motor, more likely to live next to the airport, more likely to rent the apartment lower down and with thinner walls. But controversies between communities and a noisy industry are likely to pit neighbor against worker, at least in the eyes of the worker, who may tend to see the neighbor as someone with a good job who doesn’t mind threatening some- one else’s job. This was certainly my impression when I was hanging out with the half-dozen Sheffield quarry workers while environmental experts, lawyers, and those with “party status” made their inspections of the site. “Maybe we’ll get lucky and the whole bunch of them will fall into a hole,” said a young equipment operator. Certain supporters of the quarry were quick to frame the issue as a conflict between the interests of the poet on the hill and those of the peon in the valley, between people who had come from elsewhere with money in their pockets and those who’d lived in the area all their lives with none. This is an old and bitter distinction in my neck of the woods, and one not without relevance to the politics of noise and quiet. When I first moved to “the north country,” I often wondered why some of the men I talked to spoke so loud, until I realized that they had been partially deafened by mill-work, chain saws, and tractors. I imagine that to many of these men, the idea of someone with an indoor job or a university education being sensitive to noise amounts to something like a personal insult, like holding your nose at the smell of your baggage carrier’s sweat. And to approach things from the other side, I also imagine that certain displays of noise are intended as personal insults. Power in the hinterlands graws not only out of the barrel of a gun but also out of the barrel of an exhaust pipe and anything else that makes a good loud bang. Class warfare can come down to a war of sensibility: Fuck with me and I’ll park something big and ugly across from your breakfast nook. Piss me off and I’ll teach it to sing.

But the relationship between noise and class could be more peculiar than I supposed, and this became clearer in the case of recreational as opposed to occupational noise. What I discovered was how often the appearance of class struggle was manipulated to stereotype a dispute and how often that appearance was deceiving. That fracas over motorcycles in Jerome: obviously a fight between working-class guys having a little fun on the weekend and a bunch of potters and weavers living off trust funds, right? Not exactly. If you’re looking for Marlon Brando, he ain’t here. These days a new Harley-Davidson can cost nearly $20,000, and the typical “biker” in Jerome is an anesthesiologist or investment broker from Flagstaff getting in touch with his primal side. As for the track in Louden, a third of those who attend its NASCAR races have incomes of over $40,000 a year, and the drivers themselves need a hundred grand just to get a car ready for the track.

“They try to shape the battle into good old regular folks who like racing and these rich eggheads up on the hill,” Hillary Nelson complains, and Bob Bahre was indeed quoted in the newspaper as saying that the sixteen Canterbury residents who had appealed a court ruling allowing him to expand his stadium capacity were “all wealthy people” who “just don’t care about anybody else.” This may not be as hypocritical a statement as it first seems; Bahre grew up on a hardscrabble farm, raced stock cars when the sport was strictly blue-collar in New England, and pretty marginal at that, and is still known for joining his cleanup crew in picking up litter off the race grounds. At some level, the Canterbury sixteen, who included a nurse, a salesman, and a musician, probably did seem like “the wealthy” to him. The fact remains that the money, the power, and the noise are on his side.

Back in Sheffield, I found myself taking the same second look. The “elitists” allied with Kinnell included two trailer folk who eke a subsistence living from the land, the sort of people who never count when small-town populists wax eloquent about “the people.” The self-appointed defender of South African enterprise and local common sense who wrote letters to the newspaper identifying himself with the “peasants” against the “elitists” from outside was a transplant from New Jersey. The “native Vermonter” who complained about those people “who say, ‘We’ve been to New York, we’ve had all the benefits of New York, but we don’t want you to have them,'” had children with degrees from Stanford and Tufts—which doesn’t exactly discredit her point of view but does suggest that the New York types have been a bit lax of late in maintaining their choke hold on cultural advantages. I became suspicious of any easy alignment of quiet and noise with privilege and deprivation. And I found that my own sentiments on the issue could shift as suddenly as sound on a windy day.

One Friday I followed the winding road out of Canterbury and abruptly found myself at the crowded intersection of the main highway through Louden at the start of a Winston Cup weekend. Entering a line of traffic that recalled evacuation scenes in disaster movies, I thought how stock-car racing could stand for everything I find distasteful in American civilization: the needless noise, the ubiquitous advertising, the waste of resources, the risking of human life for “special effect,” the primacy of all things Caucasian and masculine, the out-of-shape motor culture’s cherished belief that the best form of contact sport is one in which an athlete’s buttocks make prolonged contact with a foam seat, the taking over of what was once the domain of inventive amateurs by the all-hallowed “pro” and his all-but-professional fans. I stopped to talk with one young enthusiast in the parking lot of an ice cream stand near the track. “What if they could make race cars quieter?” I asked him. “Would you go for that?” With the beatific smirk of a street evangelist declaring to every passerby that “God is love,” he told me, “Noise is good.”

But as I approached the track itself, I was not insensible of a certain magnificence, of the stadium rising like an immense, elliptical cathedral out of a sprawling metropolis of RVs and white billowing pavilions such as one might have seen at a jousting tournament. Carloads and truckloads of the faithful streamed in from the highway to pay homage to a Yankee farmboy’s dream of building a world-class racetrack and a Tennessee farmboy’s dream of being able to harness enough horsepower to outrun every revenuer on the road. Hundreds of banners proclaimed his victory, checkered flags and beer brands blazoned on every one, like lilies and crosses on Easter. Mister, you want to talk about myths and civilizations and the growth of ancient cities—this is our myth and our city, and we build it in two days, more than a hundred thousand of us in a swirling blur like pilgrims circling the Ka’ba, exulting—as another race fan puts it—”in the rev and the roar.”

I stopped counting after the third or fourth anti-noise activist told me that “noise pollution will be the secondhand smoke issue of the new century.” I ought to have been happy to hear it. To say that I resent noise even more than I resent cigarette smoke is to say that I resent it very much. And yet I couldn’t hear the comparison between noise pollution and secondhand smoke without wincing. Maybe I detect in the campaign against noise, as in the campaign against smoking, a flavor of that ruthless “progressivism” that first manifested itself when families of Neanderthals began to disappear oh so mysteriously from among their Cro-Magnon neighbors. “Must be the evolution,” said the others, shifting their feet and whistling. As our society moves from a manufacturing base to an “information base,” and as more and more blue-collar workers put on the livery of the service sector, is it any surprise that we should find our old machinery too noisy and the vices of those who tend it too intolerable, that we should demand our servants keep their voices down (like that Roman master so infuriated by unexpected noises that he had his slave thrown into a pond of lampreys for accidentally dropping a tray of crystal glasses) and take their nasty habits outside, while indoors we fuss to attain the perfect funereal quiet of an online chat room?

Might at least some of the noise assailing us amount to a protest against the threat of cultural or economic extinction? “I make noise, therefore I am.” The Hispanic gardeners who recently went on a hunger strike to protest an L.A. ban on leaf-blowers said that the law was aimed at their race. In effect, they were saying that a noise identified them; silencing it was an attack on them. In a similar vein: “To everybody who told me I’d go nowhere in life: I can’t hear you.” That’s a Sony advertisement for a car stereo system that cranks out sound at 164 decibels, loud enough to kill fish, but it easily could serve as the slogan for a generation that is not so much lost as unclaimed. Maybe the best way to fight the Boomers is with something that booms.

I wonder, too, if some of our antipathy toward noise isn’t the negative form of our totalitarian consumerism, the belief that we ought to be able, as though by divine right, to achieve complete satisfaction of our every distaste no less than of our every desire. And will the ear ultimately lead the eye to more refined levels of fastidiousness? My interest in noise ordinances took me to an affluent New Jersey suburb where “hawkers, peddlers, and vendors,” as well as “yelling, shouting, whistling, or singing on the public streets,” are all prohibited by statute and where hanging up wash on an outdoor clothesline is prohibited by custom. It’s funny to imagine that any people on earth, much less well-to-do people in the wealthiest nation on earth, would deny themselves or their neighbors the inestimable luxury of making love on sun-dried, wind-kissed sheets, or the wistful hope of some enchanted morning coming upon a peddler. If you met Humphrey Bogart in heaven, would you ask him to put out his cigarette? If you get to heaven at all, will you ask them to tum down the choir?

“The Lord is in his holy temple; let all the earth keep silence before him.”

But this too: “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord, all the earth.”

I hate noise as much as anyone I know, and I can flatter myself with the names of others in history who hated it, too: Darwin, Proust, Goethe, Poe, Haydn, Chekhov. Recent studies tend to confirm Schopenhauer’s hunch: “I have for a long time been of the opinion that the quantity of noise anyone can comfortably endure is in inverse proportion to his mental powers. . . .” But I cannot forget that in addition to hating noise Schopenhauer hated the fact that he’d been born (and Poe felt that the most inspiring women were, shall we say, the extremely quiet kind). The connections worry me.

I would never want to forget what Thoreau said about the train: “when I hear the iron horse make the hills echo with his snort like thunder, shaking the earth with his feet . . . it seems as if the earth had got a race now worthy to inhabit it.” Or what James Agee said about the importance of playing Beethoven loud. I agree wholeheartedly with the motto of the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse, “Good Neighbors Keep Their Noise to Themselves,” and I try my best to practice it, but something else in me wants to cry, “Aw, go ahead” when Bob Marley sings,

I want to disturb my neighbor

Cause I’m feeling so right

I want to turn up my disco

Blow them to full watts tonight

True, whenever I take overnight accommodations, I always ask first if there are any wedding parties or traveling sports teams likely to “blow them to full watts” in the rooms nearby; yet few scenes in literature delight me as much as the one in Robertson Davies’s Fifth Business, in which an anonymous Spaniard, having complained the night before about a row he mistakes for a boisterous honeymoon (“very well for you, señor,” he calls through the door, “but please to remember there are zose below you who are not so young”), leaves flowers and this message at the door the next day: “Forgive my ill manners of last night. Love conquers all and youth must be served. May you know a hundred years of happy nights. Your Neighbour in the Chamber below.”

To all of this, I have no doubt, many anti-noise activists would say, “We love these sounds no less than you. The problem is that every single one of them, Agee’s quaint phonograph and Thoreau’s equally quaint train, the joyful noise and the rub-a-dub style, is being overpowered by the boom car and the air horn, by a cacophony that is literally making us deaf” (and that Canadian noise expert Winston Sydenborgh estimates is doubling world- wide every ten years). Blake said, “No bird soars too high, if he soars with his own wings,” but we are dealing now with the dark raptors of limitless amplification. Point granted. It was that secondhand smoke business that got to me, I guess. It was talking with Paul Miluski, the soon-to-be-without-his-lease owner of The Spirit Room biker bar in Jerome, whom I liked instantly, as I would have to like any man who plays croquet on a rooftop. Robert Frost said that he needed the poor for his work; I need a few Paul Miluskis for mine. And if they do not make at least some noise, how shall I know where to find them?

My noisy self-contradictions are very American, of course. Being an American is about living in contradiction, if it is about anything, because the glory and the tragedy of America come from our insatiable desire always to have the best of both worlds. That includes the worlds of noise and quiet, of utter freedom and inner peace. We want our own backyard version of the cloistered walk and our own Promethean stereo system as well. We want to practice Zen but mainly in the art of motorcycle maintenance. The purists, those who register one impulse or another as an enthusiasm and an allegiance rather than both impulses together as a complex form of yearning, are meeting now on the shrinking landscape and, perhaps more significantly, in the soundscape. Like radio stations on a crowded dial, their frequencies clash at certain bends in the road.

I actually take this meeting as a hopeful sign in that both of these impulses are essentially apolitical; that is, they both tend to express themselves against the quotidian sounds of the polis. Whether you choose to follow Huckleberry Finn or the Buddha, you always start by lighting out for the territories. Perhaps the exuberant noisemaker and the quiet seeker will discover that they are natural allies in spite of themselves, because each will of necessity have to appeal to the very sense of public domain and public life that once seemed anathema to their desires. To preserve either liberty or tranquillity against the passion of the other’s counterclaim, one must in the end circle back to a rational discussion at the city gates.

The other reason I can take hope from the noise issue is its ability to penetrate and subvert political positions just as sound can penetrate—and, given the right Jericho, break down—a wall. Where would you locate the right and left wings of the noise pollution issue, for instance? Everywhere and nowhere. You can see noise as a threat to the most basic principles of private property, hearth and home. In other words, you can see noise as a threat to all those things that ought to be most dear to the conservative heart. Or you can see noise pollution as a threat to “the commons,” an allusion frequently made by Les Blomberg and others in the anti-noise movement to the doomed English practice of preserving some common ground for community grazing. The soundscape is self-evidently property that no one owns, or rather that all of us own together. If it is possible to construct a “unified field theory” for our conflicting political currents, might it be found there? And if we could establish an ethic for sharing the soundscape, might that in tum pull us—by the ear, so to speak—to an ethic for sharing other forms of wealth? If any of these hopes is well founded, it may rest on nothing more sophisticated than the old wisdom of old neighborhoods, which says that the only sure way to hold a loud party without complaints from the neighbors, and with some hope of sleeping late and quietly the next day, is to invite all the neighbors to the party.

My hopes are probably not well founded, however. As we divide our world more ruthlessly into rich and poor, and the countryside into what Wendell Berry calls “defeated landscapes and victorious (but threatened) landscapes,” it is probable that we will do the same thing in regard to sound. Many of us will live in pandemonium, and a few of us will have the means to live in paradise. The permeability of the soundscape may yet teach us to recognize the flaw in that arrangement, but we are likely to interpret the warning alarm as no more than a call to move elsewhere. Most of us will continue to put our faith in our mobility, in being able to run from the noise to someplace quieter. Like our pre-human ancestors, we still respond to noise with a fight-or-flight response, which at our stage of development means weighing the relative costs of the lawyer and the realtor.

Of course, the irony of flight is the sound of flight itself. By far the largest number of noise complaints in this country have to do with modes of transportation, highway noise first of all, airport noise after that. Earlier I said that the first of two principles governing the relationship between mobility and noise is that people move to escape noise, and by moving they find it. The second principle is that people move to escape noise, and by moving they make it.

Along with fight and flight is there not a third ingrained response to the overwhelming power of noise, which is to fawn, to assume the position of joining what we cannot beat? So those who cherish quiet we dismiss as failed stoics, which may mean nothing more than that we are resigned to being cynics. In any case, I have begun to notice a curious thing about noise, which is how the pursuits disturbed or destroyed by it—pursuits such as writing a poem, watching a bird, or even looking after a child—can be made to sound so insignificant precisely because they make so little sound. Hillary Nelson told me of a day when her three-year-old son fell and hurt himself in her front yard, but she could not hear him crying over the drone of the race cars in Louden. I suspect that many will be as deaf to her complaint as she was to his cry. Kids fall all the time, right? From Jerome, Jane Moore wrote me a letter about a friend who moved out of town because she was dying of cancer and the motorcycle noise was making the process more painful. And I imagined the same cynical voice responding, “Let me get this straight. You need quiet to die?”

Actually, the time may be coming when you will not even need quiet to be dead. A German media artist who finds the notion of a quiet grave “idiotic” has recently created an exhibit of vocal tombstones, one of which “moans lustfully” when stroked: I find myself thinking about the moaning tombstone whenever someone tells me, with a faith so innocent it can bring tears to your eyes, how Technology (invoked with a capital T) is going to be our solution to the noise problem. Of course it can be, with marvelous results. In Europe, where noise reduction has a much higher place on the political agenda than it does here, roads are being built that reduce traffic noise by as much as 70 percent. Even the Harleys exported to Europe are designed to run quieter and, as an unintended result of such tinkering, turn out to have even more horsepower than their hoggish American cousins. Mechanical noise, after all, is an inefficient loss of energy (though many American consumers still equate louder volume with higher performance). So it is sometimes possible, with a little know-how, to have the best of both worlds. But for every noise we quiet, we produce another. Most of all, we continue to produce a false sense of virtual quiet by distancing ourselves from the actual noise we make. This is the ultimate form of “civilized” mobility: the removal of my actions from their effects. I don’t have to hear the printing presses that publish my words, the strip-mining equipment that feeds my computer. I’m a writer, you see. I practice a quiet occupation. Technology has carried that old suspicious adage about not shitting where you eat to a place perilously above suspicion, where highly intelligent people are capable of believing that they don’t even shit where they shit. When I tried to suggest as much to some of the movers and shakers in the noise movement-for instance, to the consultant for an airport-noise group who told me that he logs 75,000 flight miles a year in his work—the response I got was often a bit chilly. Perhaps this was due to the understandable fear that someone already in danger of being branded a crank might also be branded a Luddite. But perhaps it rather had to do with a deal already struck with the successful manufacture of the first mud brick some nine or ten millennia ago. As the consultant told me, “The absolutist approach [i.e., the one I had just proposed to him] says we must change the way we live . . . but no one’s going to stop the growth of airlines. Why tilt at windmills you can’t defeat? I wouldn’t want to stop rhe evolution of our science, even though there are going to be losers.”

So in the end the most raucous disturbance of the peace (or the most cynical response to the complaints of those disturbed) may be nothing else but the brazen form of a more discreet and universal communication, the signed version of an anonymous chain letter that the rest of us mail out every day and that comes back with interest to everybody’s mailbox sooner or later. (And sooner than later will be able to announce its arrival by moaning lustfully.) When this essay is done, for example, I will send it to New York City overnight mail because it absolutely positively has to be there, and because the other pursuits of my have-it-all life will undoubtedly push the project too close to its deadline. Overnight mail is only possible with overnight flight, which has made no small contribution to the 2,156 percent increase in air-cargo traffic since 1960. Sometime in the night the plane carrying my little meditation on noise will fly over someone’s roof, waking her or her aged father or her colicky three-month-old from a sound sleep. Wrapping her robe furiously around herself, perhaps going so far as to light a cigarette with her trembling fingers, she will curse that plane, and, to some small degree that I cannot gauge and can never hear, she will be cursing me. And those cranky old gods of Sumer and Uruk, long since deaf if not dead, will do no more than I will to help.