For two decades, I’ve lived between New York City and Oxfordshire, and when in the autumn of 2008 I came back to New York, I got a television for the first time in years. I said I wanted it in order to follow the presidential election, but it was really so I could view entire episodes of As The World Turns, not just online excerpts. As The World Turns, one of the oldest soap operas on network television, became the only program I watched; for election coverage, I went back to my laptop. On As The World Turns, impetuous Luke was also running for office, but, desperate, he stuffed the student-government ballot boxes. Honest Noah betrayed his boyfriend to the dean and moved out on him for the second time. Luke was expelled and started drinking, a danger for someone with a donor kidney. Thank goodness, he’d gone through that operation before I started watching the show.

I moved back my lunch hour and did not answer the telephone between two and three o’clock. I had my machine set so that As The World Turns recorded automatically anyway. My partner of nineteen years, my visiting Englishman, loyally watched an episode with me and then gave me a look that said this wasn’t going to be an interest we shared. I watched the whole show even when Luke and Noah weren’t featured, aware that there were viewers who forced themselves to stick with it when Luke and Noah were on. I was startled by some nasty comments about The Boys—as they were known to their fans—that I found posted in a CBS.com chat room. It was not for me to understand how anyone could resist this portrait of first love, the way the two actors managed to convey in a caress or in the whispered utterance of a name the helpless tenderness of it.

I joined the As The World Turns Fan Club and at the last minute got a ticket to the annual fan-club luncheon held in New York last spring. I tried to plan what to wear, but bristled when a friend observed that it sounded like I was getting ready for a date. The ballroom doors at the Midtown hotel were to open at half past ten that Saturday morning for the raffle of show memorabilia. I had not expected the excited noise of over four hundred people sitting down to a not-bad lunch, and certainly had not thought that I would be so humbled by the induction to come.

I was such a newcomer. As The World Turns had been on the air for fifty-two years. I was among mostly women, of all ages and sizes, but also a good number of men. A black guy on my left, in his late thirties maybe, had been watching the show for twenty-nine years, having been introduced to it by his grandmother. Others at our table were silent not because they were unfriendly; they were merely preoccupied because determined on their own interior business. We were all there for the same reason. Eventually, some thirty-five soap-opera stars were brought out onto the faraway stage at the front, one by one or in romantic pairs. The roar when Van Hansis (Luke Snyder) and Jake Silbermann (Noah Mayer) appeared made my heart pound. There they were, in the ballroom distance. We were instructed to stay in our seats until the stars had taken their positions at small tables along the walls.

I got in their line. As soon as I’d arrived at the luncheon, a black woman had given me a Luke and Noah Fan Club nametag. Wearers of these tags fell into conversation right away. Young people had flown in from Paris or cut short a stay in Moscow to come. Twins from Texas were going to take in a Broadway show. The line was moving. It moved again, until the room felt too warm and bright. The girls directly in front of me stopped talking. We couldn’t hear the conversation a few feet ahead of us, but we caught the music of their voices. Someone had just presented one of them with an action-hero doll.

Then I was there. The table stood between us, but there they were, courteous, flawless, and camera-ready. I was dimly aware of a woman to my left whose function was to take the picture when you went around the table and stood between the stars, but I didn’t have a camera. Instead, we shook hands. They read my nametag. I could barely look at them. I produced a glossy photograph of them that I’d bought that afternoon. When they weren’t looking at me, I could look at them. I told them they were great. They thanked me and finished signing. I shook their hands again, which seemed to surprise one of them. Unable to meet his eye, I followed his black felt pen as he shifted it from one hand to the other. It was time to turn and go and I’d acted like a crazy person.

I didn’t look back until I was halfway down the line again. There they were, putting their arms around someone’s shoulders, smiling into the flash. I still couldn’t think of a thing to say to them. They were saying goodbye to someone else, and one of them looked down the line, as if seeing it for the first time, the longest of any in the ballroom. Then he was smiling at someone new. To watch their professionalism recalled me to myself.

I struck up a conversation with a black woman in a hat who was ecstatic that she’d won in the raffle large posters for both herself and her daughter. She was a fan who knew what she wanted. Every year she came to the luncheon to say hello to her favorite star, whom she’d followed to As The World Turns from a soap on another network. I asked if she thought my nametag identified me as a member of a lunatic fringe. She said the cast of As The World Turns were very good to their fans and their fans were good to them. We loved them and it was rare that a character stayed dead.

Another middle-aged black woman said that she enjoyed watching the characters get through problems not unlike her own. Kicked out of school, Luke had started a foundation for social justice with a trust fund given him by his biological father, a Eurotrash type whom he loathed. Because her mother had been denied a share of the family fortune, a distant cousin of Luke’s hatched a scheme that led to Noah’s and then Luke’s abduction. As of the luncheon, they were still being held hostage. I asked the woman if her problems were of that nature. “Yes, indeed.”

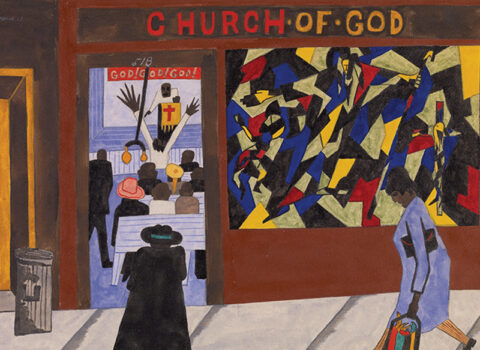

She remembered when Lauryn Hill was a young girl on the show in the early 1990s, singing at the show’s first interracial wedding. Beyond us, at the black table, I could see Luke’s half-black cousin, her black private-detective father, the town’s black police lieutenant, and his black attorney girlfriend, but, snow queens that we were, the black woman and I didn’t make a move in their direction. Stage veteran Elizabeth Hubbard, who plays Luke’s maternal grandmother, says on the As The World Turns official website that the Memoirs of Madame de la Tour du Pin is her favorite book. Before the luncheon, I’d imagined us discussing Madame’s surprising glimpses of blacks in Revolutionary France and of slavery in Albany, New York, which blacks had burned down a couple of years before Madame, however enlightened, arrived to become a slave owner herself. But I didn’t join the crowd around her chair either. I took a last look down that line I’d been in, and although I don’t drink or follow baseball, I went to a Times Square bar and watched the Yankees, already losing twenty to two.

YouTube first showed me Luke and Noah. Two summers ago, while sitting in the English countryside, enjoying scenes from German, French, and British soap operas that featured gay characters, I came across a forty-nine-second video from American TV, posted by one LukeVanFan, “Luke and Noah’s Story—ATWT—Part 41—The Kiss.” In the brief clip, a blond youth begins to tie the tie of a dark-haired youth who stares at him. Close-up: “What’s wrong?” Beat. “Nothing.” The dark-haired youth then leans down, and they kiss. The blond looks up in brave delight. They close their lovely eyes and kiss again, deeply. Scene. “The Kiss” had registered over a million hits.

This romantic collision had been controversial in the United States, where some right-wing groups and church bodies objected to the characters’ being “teenagers” and also to a network’s airing in the American afternoon a kiss between young men. I gathered that an international campaign was underway, or had been, to save this storyline of gay love between incoming university freshmen in the fictional town of Oakdale, Illinois. One link urged supporters of Luke and Noah to write to CBS and to Procter & Gamble, the owners of As The World Turns, and listed telephone numbers for the network’s call-in polls. CNN had picked up the story, but by the time I dialed the number, a recording said the poll had closed.

Fortunately, the campaign seemed to have succeeded: As The World Turns announced that it was standing by its Luke and Noah storyline. I was able to catch up on all the plot I’d missed because LukeVanFan excerpted the Luke and Noah scenes from each As The World Turns episode and put them on YouTube. So. Noah had a girlfriend when he kissed Luke, but Luke helped Noah to face the truth about himself, after which Noah’s father, a retired U.S. Army colonel who only pretended to accept his son’s being gay, shot Luke while on a fishing trip with the two boys. Luke was left paralyzed, but patient Noah had his sad new boyfriend out of that wheelchair and dancing by New Year’s.

Luke and Noah have been through a lot since their first Christmas together three years ago at the Snyder family farm, where Luke’s cookie-baking paternal grandmother declared Luke’s bedroom off-limits to Noah, not because they were gay but because she wouldn’t let her straight children at Luke’s age share beds under her roof with their boyfriends or girlfriends either. The Boys got through their first Christmas, New Year’s, and Valentine’s Day without sex, and laughed in one scene that the four-meat sandwich Noah was eating was a sublimation. But then an Iraqi girl found Noah and claimed that his father had been her mother’s protector during the war. To keep her from being deported, Noah married her. The authorities had to be persuaded the marriage was real. Noah moved away from the farm, and Luke watched the Iraqi girl grow ever more dependent on his boyfriend with the cool voice.

The sham-marriage story line—“Cock Block,” one fan called it—went on until the Writers’ Guild strike ended in the winter of 2008. Disgruntled fans of The Boys saw the network’s stalling as a waste of the young actors’ talent. Hansis had been nominated for a Daytime Emmy as Outstanding Young Actor in a Drama Series, and as the soap world’s latest supercouple, Luke and Noah, or rather Hansis and Silbermann, were presenters at the 2008 awards. The determination among fans when Hansis didn’t win led me to suspect that the campaign to save the soap opera’s gay story line had been refined into a lobby to give The Boys more air time and better plot situations, and, above all, to let their characters have sex with each other at long last.

LukeVanFan kept count of how seldom Luke and Noah kissed, and plenty of fans got fed up with the double standard that let a heterosexual teenage couple, played by actors younger than Hansis and Silbermann, go at it. Then, the summer before last, after Noah’s father escaped from jail and kidnapped Noah’s Iraqi wife; after Luke followed Noah to New York City, where he had gone to rescue her; after Noah’s father leapt into the Hudson River and drowned rather than be taken back into custody—Noah broke up with Luke in high soap-opera style. The Boys rocked, proving that they weren’t just waxed torsos and matinee faces. I watched the break-up scenes over and over. I couldn’t help myself.

Because of Luke and Noah, I’d lost it. I had to excuse myself to houseguests as I reeled to my computer to see if there was anything new from Oakdale. My partner, my reserved Englishman, made no comment when he saw that I’d chosen as my screen saver an image of Luke tying Noah’s tie. Our houseguests smiled when I informed them that everything was going to be okay, since Entertainment Tonight had revealed that Cyndi Lauper would reunite the chaste lovers on a visit to Oakdale in a special appearance around July Fourth. Sure enough, the wild girl sang them into a passionate embrace, but Noah, his marriage annulled, told Luke that he still couldn’t have sex with him, because he’d enlisted in the Army and was leaving for basic training early the next day.

Jean Passanante, the head writer of As The World Turns, came in for a great deal of criticism from fans, but she and her team had to be doing something right if we were freaking out. And what if Ms. Passanante got offended? Didn’t she or Chris Goutman, the show’s executive producer, have the power to cut down The Boys with a rare tropical disease or a hit-and-run? (Hansis was under contract, but Silbermann wasn’t.) Although I had joined the group, I worried that the chatters on the LukeandNoahFans.com message board were too young for me to commiserate with. A middle-aged queer, I could not break cover, and, as a middle-aged black man, I was embarrassed that these white boys from this melodrama mattered to me anyway.

I could not comfortably explain my staying up late in England to see if LukeVanFan had posted a new excerpt after he’d got home from work over there in Michigan. European soap operas have franker love scenes between their gay characters; cable television in the United States has made familiar a kind of quality family drama that includes the sympathetic gay sibling. We’ve been through clean and self-satisfied Will & Grace, ecstatic and unprecedented Queer As Folk, and when it comes to gay heroes, Omar from The Wire has no peer. How could the production values of daytime television compare with those of prime time? What was As The World Turns doing for gay people that hadn’t been done before?

Frustration had me hooked, no doubt, but Oakdale had also become for me a battleground over how to tell a gay story in the cultural mainstream. “There are many ways to tell a story, realism is just the most dull,” says the sexy gay black soap-opera writer in Richard Glatzer’s sophisticated 1994 film comedy, Grief. Defenders of soap opera sometimes point to the genre’s social usefulness, what it can teach an audience about breast cancer, bulimia, or drug abuse. But what seemed to be going on was a struggle between unseen forces over the direction Luke and Noah’s story should take. Noah couldn’t go through with his enlistment and ended up back on the Snyder farm. Luke told him it was lame to blame his grandmother’s rules for their not having sex.

There seemed little chance of anything more explicit in the daytime slot. The Boys had got back together at Christmas, but on New Year’s Eve, Noah believed he had reason to walk out on Luke’s trembling smile yet again. Then, lo, one day not long after President Obama’s inauguration, Noah kissed Luke in order to shut him up when they were snarling at each other in the town square. They hurried away to hook up offscreen, much to the derision of fans who had hoped to see the fireworks.

To have scripts about them getting gay bashed or being discriminated against provided opportunities to preach tolerance, but what young fans wanted was for Luke and Noah to be treated like other couples on the show. I remember arguments over the image of black people in popular culture: whether to be seen as a social problem isolates from the mainstream the very minority well-meaning people say they want to include. Luke and Noah, however, are emissaries of a generation for which Difference is no longer such a big deal. It is a generation that doesn’t have a problem with the implied equality in not making a fuss over a member of a minority group, in accepting that person alongside everyone else without a big demonstration.

All along, Luke has been shown as surrounded by his loving family, in contrast to the orphaned Noah. Luke’s horse-breeding father doles out relationship advice to his gay son in the kitchen or while they’re chopping wood, no matter what is going on in his own stormy marriage. Luke’s pill-popping, heiress mother flipped when Luke came out three years ago, but she now adores Noah. Luke and Noah aren’t portrayed as rebels. What is subversive about them is their normalcy. When I was young, gay images were either camp, coded, high-brow, or late-night. Although there were middle-class coming-out novels in the 1970s following the rise of the Gay Liberation movement, there wasn’t anything like the free-of-guilt-or-shame Luke and Noah story line anywhere in mainstream culture. Dynasty’s short-lived gay son was, like AIDS, years away.

In May, I was on Marco Island, off the Gulf side of Florida, longing for a spliff. I was at Soapfest, which I’d somehow assumed would be like a weekend seminar on soap operas. But Soapfest, an annual charity event, is for fans to meet the stars in relaxed settings, from Saturday evening parties to a Sunday afternoon cruise in Gulf waters.

The actors are drawn from several shows, not only As The World Turns. Founded in 1998 by Pat Berry, Soapfest raises money for charities that help children and young people who have autism and learning disabilities. The stars come down a day early to meet the kids and to make paintings with them, which are then sold at Soapfest.

CBS had just announced the cancellation of The Guiding Light, a soap that had been on radio and television for seventy-two years. The Soapfest organizers were passing out mourning ribbons and getting up a petition. It was going to be all right to give in to the intensity of my adventure, because everyone else was in full-blown fan zone. There was an auction of items from studio wardrobes and a raffle for prizes, such as an autographed Frisbee. Also up for grabs, a tour of the As The World Turns set in Brooklyn with—I couldn’t believe it—Hansis and Silbermann. A trip to Oakdale, a trip to Oakdale—I dropped out of the bidding way past what I could have justified back home, but vibrated from the terror of having had Luke and Noah’s attention every time the auctioneer looked at me.

At the opening-night dinner attended by one hundred or more gleeful souls, my table was graced by Ewa da Cruz, the spectacular Norwegian-Egyptian beauty from As The World Turns. With her came her colleague Trent Dawson and his parents. I wasted time that night lurking in the shadows of my brain whenever I forgot that these gorgeous, wonderfully groomed human beings weren’t there to check me out; they were professionals donating their time, prepared to accept a certain amount of awkward scrutiny from me. Miss Cruz could not have been more perfect. She even has a degree in nursing.

Hours later, at a late-night bash on an off-season street, a few stars worked behind the bar, the drinks tickets and their tips going to charity. As the night got loose, some hunks ended up shirtless before the cameras that were everywhere. Hansis and Silbermann did not tend bar, but they thanked you with surprise if you ran up to where they stood in a grove of girls and thrust a Red Bull and Stoli into their hands and then ran off. There was disco, there was karaoke, and I saw many badges that proclaimed my same obsession: nuke forever. For the drinkers, maybe things were beginning to blur. Austin Peck, the well-built actor who plays Luke’s first cousin once removed, had to use both hands to pry himself from the grip of a pleading fan. The frothy black woman I was sitting with said that when she first started coming to Soapfest, young girls knew how to behave.

On the upper deck of the Marco Island Princess the next day, my last chance ever to connect with heaven, I met a forty-seven-year-old mother of four from my hometown, Indianapolis. We marveled that two black people from “Nap” could possibly not know anyone in common. But we had our passion for As The World Turns. I heard myself say that I was probably seeking out black women at these fan events in order to hide from myself, or from them, the black race, how hung up I was on Luke and Noah. Kim pulled down her shades and said that that was fine by her. I said they should bring back Luke’s older half brother, played by Akim Agaba, and she high-fived me on that.

Fans sat in the shade or sunned themselves, ate from the buffet, trailed the stars to the bathrooms, sprang in and out of various orbits. Kim asked Van Hansis to come over and talk to me. I really wanted to quiz him about the show, but I didn’t want to put him on the spot, so once again I couldn’t think of a thing to say. Michael from Chicago reassured me that if Jake Silbermann had noticed me filming the tattoo just below his left calf, he was being gracious about it. My experience of former students or the children of friends now grown up did not help me to feel that I’d bridged a generation gap with them, but then Hansis, with his B.F.A. in theater from Carnegie Mellon, and Silbermann, with his B.A. in theater from the University of Syracuse, are not like the young adults I know, because only they have the power to create Luke and Noah before my eyes.

I’d stumbled into the group behind the websites VanHansis.net and JakeSilbermann.net. It was moving to witness the sweetness of the rapport between the two young actors and the fans they’d come to know, and how protective those fans were of their trust. Quayside, they said farewell and knew how to let them go. I was honored when asked to a poolside after-party by this elite brotherhood or sisterhood. One of us.

Vicky from Fort Lauderdale said that a scene of The Boys jumping on a bed still made her cringe. She had sent the program’s executive producer a wall clock with the message it’s time painted on its face and images of The Boys for each of the hours. George from Boston successfully agitated for atwt.net to put online a deleted scene showing Luke and Noah nestling on a public bench. I’d fallen in with a militant faction of the As The World Turns Fan Club, led by the likes of Sherry, a former Rockette in her sixties and the victor in the auction for the studio tour. They knew LukeVanFan as Andy and were sorry that he, a hero, wasn’t at Soapfest this year. I watched the sunset with a dozen members of this activist wing, friends reunited or email correspondents meeting at last, brought together by a mad feeling.

The list of straight guys who got their big break playing a gay role is by now absurdly distinguished, as is that of actors we now know to have been gay who played straight roles back in the day. I thought this sort of prejudice was what Jonathan Russo, president of Artists Agency of New York, had in mind when I talked to him not long ago. For the past twenty-five years, Russo has represented top writers, producers, and directors in daytime television. He shocked me when he said that for soap-opera stars like Hansis and Silbermann to go to Hollywood from As The World Turns meant “no more than if they were getting off a bus from Cleveland.” Daytime stars have a hard time getting into anything else, he said; crossovers were rare anywhere in the industry.

LukeVanFan’s “The Kiss” has increased to well over 2 million hits, but soap operas in general are doomed. Russo sketched a picture of inexorable decline that has nothing to do with demographics or the quality of the production. Television and viewer habits have changed. In the 1980s, at the peak of the soap opera’s popularity, three networks dominated programming. Then there were ten cable channels, and now there are 150. The afternoon viewer is besieged by cooking, travel, health, gossip, religious, news, porn, and shopping channels. Meanwhile, thousands of websites are vying for fractional shares of a dispersed audience. The market has become too competitive, and nobody is cleaning up.

Taken together, all the daytime dramas now on network television don’t have the ratings of what just General Hospital had ten years ago. As The World Turns is a “1-rated show,” meaning that it draws an audience of roughly 1 million viewers every day. That is—unbelievably—not enough of the available audience. Then, too, a soap opera is expensive, costing three or four times more than a reality-TV show. Russo added that the networks know what is happening, because they are investing in cable channels, in effect programming against themselves. The networks had “cut their own throats by over-commercializing the hour,” allocating twenty-two minutes of advertisements to thirty-eight minutes of program, and at a time when the attention span of the MTV-conditioned audience has been so famously reduced.

The commitment a daytime drama asks of the viewer is enormous. Most people I know who watch a blockbuster serial drama and do not have kids at home catch the series on DVD, in sessions that sometimes last all night. You could go back into LukeVanFan’s videos on YouTube and have the same marathon experience, but when watching As The World Turns on a television screen the characters become really big and more cinematic. When you are on the computer, you are much bigger than what you’re watching, and you may prefer to be overwhelmed.

It can be as powerful as a habit. You do stalk them in your mind. I still don’t know what to do with the shirt I won in the Soapfest raffle, the red one Noah wore to Cyndi Lauper’s concert. “Throw it away,” my own patient boyfriend said. I didn’t tell him how much I’d really spent on those raffle tickets. “Out it goes.” Last summer, Noah’s father returned from the dead to bum everyone out, and I was still being urged to write letters to CBS. This fall, Van Hansis was again up for an Emmy, this time as Best Supporting Actor. He and Silbermann, dressed to the nines, were presenters again. Luke and Noah were having big problems again. And groups of As The World Turns fans reported following the off-Broadway appearances of cast members, sure that Russo is wrong about the welcome this generation of soap-opera actors would get in Hollywood.

Just before Christmas came the news that the show had been canceled. Fans are still planning to go to Soapfest in May—the show will shoot until June and air until September. Sherry the former Rockette and Mike from Chicago have even volunteered to help Pat this year. I, however, came to my senses a while ago. The As The World Turns scripts got so soft I had to stop watching. I gave up. I don’t care that poor Noah is blind after an accident on the set of his student film. The show threw itself away. It could have been so great. CBS said they were thinking of putting a game show in its place.

In the time Luke and Noah have left, they are innocent, whatever they get up to. (“And if you want to see some beautiful boys, I’ll see your Luke and Noah and I’ll raise you a Tim Riggins any day,” a woman psychoanalyst addicted to Friday Night Lights said to me.) They call out to an ideal self, to the person I could have been and of course to the person I couldn’t be. They conjure up the white boy I fell in love with at their age. You feel an intimacy with them, because you have been with them in their most private moments, and the fact that they’re not real, that they don’t really have private moments, doesn’t apply. It’s about living again with the bliss and pain, because this kind of love is impossible; it can’t last.