Much of the story of twentieth-century art can be told as a series of acts of vandalism. Cubist collage attacked the expectation that a painting should look like something in the world. “In my case,” Picasso said, “a picture is a sum of destructions.” Abstract painters criticized Cubism for not going far enough: “Cézanne broke the fruit dish,” Robert Delaunay reportedly said, “and we should not glue it together again, as the Cubists do.” Marcel Duchamp, not satisfied with assaulting painting from within, abandoned the medium after 1918, turning his attention to the presentation of ready-made objects as art, the most infamous of which was the urinal, entitled Fountain, he submitted to the American Society of Independent Artists under the pseudonym “R. Mutt” for its inaugural exhibition, in 1917. Whatever else Duchamp’s gesture was — a provocative way of blurring the boundary between art and mundane objects, a critique of the idea of authorship — it was also a metaphoric micturition on the history of creative expression. Another work of Duchamp’s, L.H.O.O.Q., consisted of a cheap postcard-size reproduction of the Mona Lisa, on which he drew a mustache and goatee. Pronounced aloud in French, the title sounds like Elle a chaud au cul, which translates colloquially to something along the lines of “She’s horny.” Duchamp’s focus was on degradation, setting the stage for the deskilled and frequently scatological experiments of a range of progeny, from Dubuffet to Warhol to the Andres Serrano Piss Christ that so pissed off Jesse Helms.

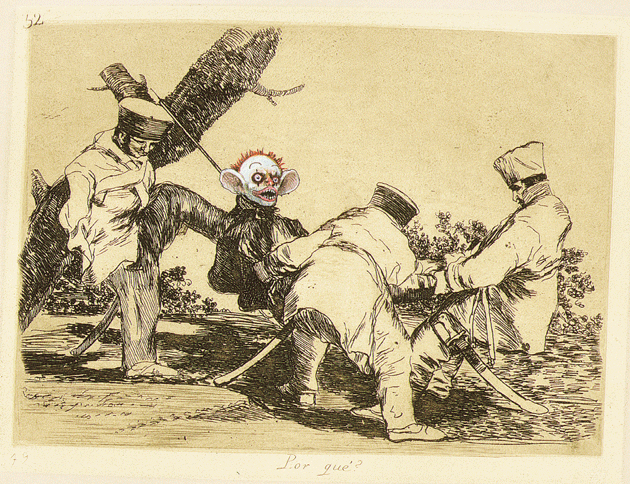

From Insult to Injury, 2003, a portfolio of eighty of Francisco de Goya’s Disasters of War etchings, “reworked

and improved” by Jake and Dinos Chapman, 14 9?16? × 18 1?2? © The artists. Courtesy White Cube, London. Photograph by Stephen White

As a kid, when I first saw images of Jackson Pollock at work, I thought I was watching somebody vandalize a painting, not create one: the canvas was on the floor, paint was splattered and poured, and he was indifferent to the ash falling from his cigarette. Trash — nails, tacks, buttons — can be found encrusted in his paintings’ surfaces. In 1953, Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning drawing; now in the San Francisco MOMA, it’s widely considered a landmark of postwar art — ghostly traces in a gilded frame. In 1966, Gustav Metzger and others hosted the Destruction in Art Symposium in London, inviting a number of participants, especially those who worked by burning, cutting, tearing, and blowing up. Metzger, the author of the manifesto “Auto-Destructive Art,” conceived of such art as “an attack . . . on art dealers and collectors who manipulate modern art for profit.” Some in the London press referred to it simply as “organized vandalism.” (Metzger’s subversions were the subject of a 2011 retrospective at the New Museum, in New York.) One notable antecedent of the conference was the work of Jean Tinguely, whose giant “méta-mécanique” Homage to New York beat itself to death in the MoMA sculpture garden on March 17, 1960. Autodestruction was also a theme and technique in Body Art, performances in which flesh was medium: Yoko Ono inviting an audience to cut away her clothing; Vito Acconci biting himself; Chris Burden being shot, or nailed to a car.

Examples could be multiplied easily, almost endlessly — this highly selective catalogue only takes us up to the Seventies; what’s clear is that modern art is inseparable from the destruction of modern art. Demolition, defacement, and debasement are not just fates artworks suffer at the hands of vandals; they’re often what those works are. It’s against this backdrop that vandals often claim to be artists — claim that they are moving the history of art forward by renovating received ideas or performing what artists and critics have come to call “institutional critique” — and that artists claim to be vandals, attacking the notion that art is property and ridiculing existing canons of taste. It’s precisely when vandals and artists are so difficult to tell apart that an act of vandalism can raise important and often uncomfortable questions about how we really define and value art.

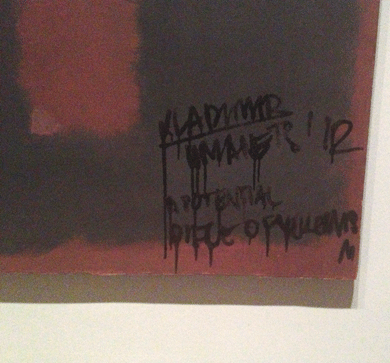

On Sunday, October 7, 2012, a twenty-six-year-old Polish man named Vladimir Umanets walked into the Tate Modern and wrote vladimir umanets ’12 a potential piece of yellowism in the bottom right corner of Rothko’s 1958 Black on Maroon with a black paint pen. It was an act made to be googled, and googling it led to Umanets’s blog, which featured the so-called Yellowism manifesto, a work of Neo-Dadaist nonsense. Yellowism, the movement Umanets founded with his friend Marcin ?odyga, “is not art or anti-art”:

Examples of Yellowism can look like works of art but are not works of art. We believe that the context for works of art is already art. . . . Every piece of Yellowism is only about yellow and nothing more, therefore all pieces of Yellowism are identical in content — all manifestations of Yellowism have the same sense and meaning and express exactly the same. . . . Yellowism can be presented only in yellowistic chambers.

Mark Rothko’s Black on Maroon at Tate Modern, London, defaced by Vladimir Umanets on October 7, 2012 © Tim Wright/Rex Features/AP Images

Umanets, who argued that he was working in the tradition of Duchamp, was resolute that his action was not vandalism, as he believed it increased the aesthetic and financial value of the Rothko:

With my signature this work will be much more valuable a work of art and also financially, because I changed the meaning. Someone who removes this signature will be an asshole.

The previous June, Uriel Landeros, a twenty-two-year-old artist from Houston, approached Picasso’s Woman in a Red Armchair in the city’s Menil Collection and spray-painted a stenciled image of a matador and bull along with the word conquista onto the canvas. Landeros described his act as one of social and political defiance: “It’s just a piece of cloth,” he said. “What matters most is the people who are suffering.” Another museumgoer filmed the attack on his cell phone; a guard appears just in time to insist that picture-taking is forbidden. Landeros’s paintings were later exhibited at a gallery in Houston, an event that received more outraged attention than his tagging the Picasso. The decision to treat the vandal as a “legitimate” artist was almost universally condemned.

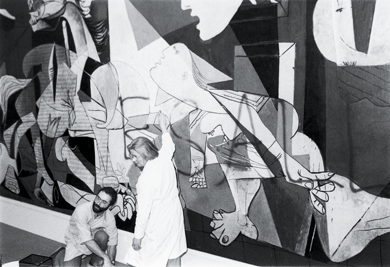

Employees of the Museum of Modern Art in New York removing the words KILL LIES ALL from Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, spray-painted there by Tony Shafrazi on February 28, 1974 © AP Images

Umanets’s and Landeros’s acts recall other destructive performances in museums. In 1993, at the Carré d’Art in Nîmes, an exhibition included a copy of Duchamp’s Fountain. On August 24, a sixty-three-year-old man named Pierre Pinoncelli urinated into the urinal, then hit it once with a small hammer before guards intervened. During the ensuing trial he explained that his “urinal happening” was intended to restore life to what had become a mere monument; as the critic Leland de la Durantaye explains, “When the prosecution accused him of ‘vandalism,’ he was indignant, claiming that, on the contrary, he had added value to the work.” While the other urinals in circulation were “faceless replicas,” this particular copy “now had a history and was thus immeasurably more valuable than before.” (Urinating on a Duchamp is a mini-tradition: Yuan Cai and Jian Jun Xi, two British-Chinese artists, pissed on Fountain in 2000 at the Tate. “As Duchamp said himself, it’s the artist’s choice. He chooses what is art. We just added to it,” Cai explained. Spray-painting a Picasso is also familiar: in 1974, Tony Shafrazi — then an artist, now a well-known art dealer — sprayed kill lies all on Guernica. “I wanted to bring the art absolutely up to date, to retrieve it from art history and give it life,” he said at the time.)

Pinoncelli had already had a busy career. Among other undertakings, he’d doused the French culture minister André Malraux with red paint; he’d robbed a bank at gunpoint but taken only ten francs; he’d cut off the tip of one of his fingers in a performance in Colombia in protest against the FARC. On January 4, 2006, Pinoncelli again vandalized a Duchamp. This time the happening was sans urine: he walked into the Centre Pompidou and hit another replica with a hammer, then more or less repeated his original arguments at trial. The courts required him to pay more than €200,000 in damages.

Few, if any, were willing to take Pinoncelli’s acts seriously as art. According to the art historian Dario Gamboni — the author of an excellent (and, interestingly, the only) book on modern art vandalism — when the French artist Benjamin Vautier (known simply as Ben) demanded that Art Press acknowledge the Nîmes attack as an artistic intervention, the editors replied:

[He] has done all that only for the Press and not for art, he would have done anything to be talked about, one cannot inscribe his name in the history of art while removing every meaning except that of whimpering for publicity.

(The translation from the French is Gamboni’s.)

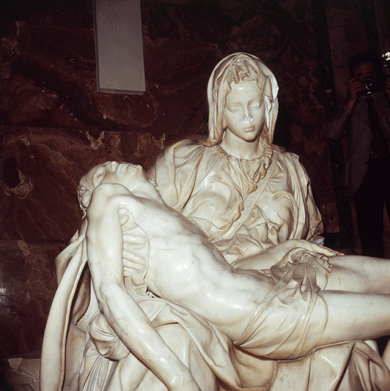

Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican, following an attack by Laszlo Toth on May 21, 1972, that noticeably damaged the Virgin’s face © Scala/Art Resource, New York City

Gamboni himself questions Pinoncelli’s claim to be an artist. “Pinoncelli,” he says, “could not give a convincing internal explanation of his resorting not only to ‘urine’ but to a hammer” and “showed a poor knowledge” of the history of Fountain. While conceding that Pinoncelli is not necessarily “deranged,” and that “the search for public acknowledgment” often motivates artists, Gamboni writes that “the importance of the attention-seeking element” in Pinoncelli’s act, “as well as its lack of coherence and relevance from an ‘artistic’ point of view, bring it exceptionally close to the ‘pathological’ cases ” of vandalism — cases like that of Laszlo Toth, who, believing himself to be the risen Christ, took a hammer to Michelangelo’s Pietà in 1972.

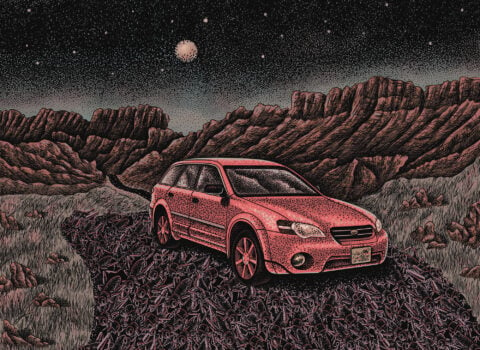

How would showing that Pinoncelli’s gesture of what he termed “creative destruction” was inconsistent, incoherent, unsophisticated, or even a little deranged prove that it was merely vandalism and not art? If a critic were to review a show in a gallery and find it incoherent and attention-seeking, she might contend that the work was horrible — but she would almost certainly assume that it was horrible art. Charges of incoherence and irrelevance are often leveled at artists without that making them vandals. It is quite easy to argue that Umanets and Landeros and Pinoncelli are bad artists — derivative, sloppy, stupid. And it is easy to argue that they are merely destructive — but then performative destruction has a long and sanctioned history in the avant-garde. (And not just the destruction of one’s own work or an attack on an abstract idea. Recently, the British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman purchased, and then drew on, Goya prints, and this year Gaylen Gerber bought and painted over two ceramics by Lucio Fontana.) If we resort to claiming that what sets vandals apart is that they compromise valuable objects, that the originals aren’t their property, or that they violate the contract between the museum and the public, we run up against the fact that the rejection of beauty and resistance to the market have been rhetorical staples of avant-garde art for half a century or more.

The speed with which artists and critics and institutions categorize figures like Pinoncelli as vandals and not radical artists betrays an open secret in the world of contemporary art: nobody is supposed to take those vanguard ideas too seriously. Like some kind of village idiot, a vandal takes literally what we’re only supposed to pretend to believe: anything can be art, traditional media must give way to conceptual performance, and the moneyhungry art world must be subject to ruthless critique.

I should admit that I’ve often felt threatened by vandals. I have secretly envied their passion and commitment, perhaps particularly the “pathological” ones. For many of my generation who grew up under the dominance of Warhol’s cool, stylized stupidity, who grew up in an era Fredric Jameson said was characterized by the “waning of affect,” the intensity of the vandal’s response to an artwork can inspire a kind of anxiety, almost jealousy. Some vandals seem to suffer from something I’ve felt a little bad about not suffering from: Stendhal’s syndrome.

According to the Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini, Stendhal’s syndrome — also known as “hyperkulturemia” or “Florence syndrome” — is a psychosomatic condition in which museumgoers are overwhelmed by the presence of great art, resulting in a range of responses: breathlessness, panic, fainting, paranoia, disorientation. The condition is so named because of Stendhal’s account of his visit to the Basilica of Santa Croce:

I was already in a kind of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence and the proximity of the great men whose tombs I had just seen. Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty, I saw it close-up — I touched it, so to speak. I had reached that point of emotion where the heavenly sensations of the fine arts meet passionate feeling. As I emerged from Santa Croce, I had palpitations (what they call an attack of the nerves in Berlin); the life went out of me, and I walked in fear of falling.

When I visited Florence last summer, the life went out of me only because of the tourists; I couldn’t see the art in the Uffizi for all the cameras. While Magherini does not link Stendhal’s syndrome to acts of vandalism, others have speculated that some attacks on artworks might result from such bouts of supersensitivity.

The question that serves as the title for Barnett Newman’s series of large canvases Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue was answered in a shockingly direct way by Josef Nikolaus Kleer on April 13, 1982. As Gamboni describes it, Kleer, a twenty-nine-year-old veterinary-medicine student, entered Berlin’s Nationalgalerie through a rear entrance while the museum was closed, made his way to the room where a Newman canvas was hung, picked up one of the plastic rails that were arranged on the ground to keep visitors from getting too close to the painting, and struck the canvas violently. He also punched it and kicked it and spat on it. According to Gamboni:

He then placed several documents on and around the damaged work: on its blue part, a slip of paper inscribed “Whoever does not yet understand it must pay for it! A small contribution to cleanness. Author: Josef Nikolaus Kleer. Price: on arrangement” and “Action artist”; on the ground in front of it, a copy of the last issue of the magazine Der Spiegel, with a caricature of the then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher . . . ; in front of the red part, a copy of the “Red List,” an official catalogue of remedies published by the German pharmaceutical industry; in front of the yellow part, a yellow housekeeping book with a second slip of paper carrying the inscription “Title: Housekeeping book. A work of art of the commune of Tietzenweg, attic on the right. Not to be sold”; finally, lying somewhere on the ground, a red cheque-book. These items enabled the police to find the culprit quickly.

Kleer’s violence was motivated, he would maintain, not only by outrage that a work of art could cost so much but also by the intensely negative effect the canvas had on him. One significant inconsistency in Kleer’s account of his attack is that he said it was inspired at once by a sense of Newman’s fraudulence — Kleer believed himself “capable of making a comparable picture for a fraction of the acquisition price” — and by a sense of Newman’s tremendous power: standing before the work, Kleer reported having felt an overwhelming fear.

Newman was interested in the sublime, not the beautiful — and sublimity has always been associated with terror, with the sensation of being undone, a “fear of falling.” Kleer’s use of part of the plastic barrier as a weapon is almost an ironic homage to Newman, who for a show at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951 posted a note on the wall that read: “There is a tendency to look at large pictures from a distance. The large pictures in this exhibition are intended to be seen from a short distance.” Kleer refused all distance — “I touched it, so to speak.” (Newman’s canvases have been attacked several times since. Four years after Kleer battered Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue IV, a thirty-one-year-old man named Gerard Jan van Bladeren slashed Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III in Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum with a knife. Eleven years later, at the same museum, he slashed Newman’s Cathedra.)

Was Kleer so struck by the work that he had to strike back, just as, in 2007, a thirty-year-old woman, Rindy Sam, claimed to be so transported by a white panel of Cy Twombly’s triptych Phaedrus that she spontaneously kissed it, smearing it with red lipstick? (“There is also a madness,” Socrates says in his dialogue with Phaedrus, “which is a divine gift.”) This hyperkulturemia of certain aggressors can make the average art lover among us appear anemic. I suspect that most of us are more like Stendhal’s protagonist Fabrice, in The Charterhouse of Parma, than we are like Stendhal himself (assuming we believe the notoriously unreliable author’s account); Fabrice wanders around in confusion during the Battle of Waterloo, wondering, again and again, if he’s been in “a real battle,” if he is participating in history. I have often wandered around museums in a similar state, sidling up to various canvases, asking myself: Am I being sufficiently moved? Am I having a genuine experience of art? The vandal who cuts or kisses a canvas seems to have no doubt.

Or what if what I’m really admiring when I look at art is money? Everybody knows that art can be worth a tremendous amount of it — that the rich park their surplus cash in one artwork or another, that even artists interested in “dematerialization” usually produce souvenirs of their performances that can be sold by galleries. But we tend to deny prioritizing art’s economic value; we say we appreciate it for its beauty, for its conceptual power, whatever. These things are not always mutually exclusive, of course, and many people are explicit that art is a business (Warhol: “Good business is the best art”). But unlike most businesses, the art world typically asserts that art is first and foremost something other than a commodity.

There is a rationality to disavowing economic interest, in part because such disavowal leads to the accumulation of what the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called “symbolic capital” — prestige, authority, an aura of purity and authenticity — which actually helps you sell your product. It’s perhaps easier to imagine denying that art is a commodity when talking about a Rembrandt or a Rothko than when talking about a Warhol print of a dollar sign or a Jeff Koons balloon dog. But I would argue that much, if by no means all, of contemporary art since Warhol assumes a posture of monetary disinterestedness, one based on criticism of the market itself. Walk through the galleries of New York’s Chelsea or Lower East Side and you will find works that claim to be a critique of capitalism or the commodification of art: recontextualized porn that attacks the capitalist spectacularization of sex, sculptures made of a devalued currency, and so on. Such art might be brilliant, or disturbing, or derivative and predictable; regardless, it is very much for sale.

Duchamp considered anything art so long as it was branded by the artist’s signature. (Indeed, Duchamp — in a gesture Umanets might have had in mind — once signed someone else’s mural at the Café des Artistes and then declared it one of his ready-mades; though destroyed, it’s sometimes listed among his works.) Scores of artists since have, like Metzger, seen their art as “an attack . . . on art dealers and collectors who manipulate modern art for profit.” But a profit can be made by selling attacks on profit because they earn dealers and collectors more symbolic capital, allow them to appear above the monetary. As long as the “attack” can be repackaged as salable, it’s art. “Vandalism” is the word assigned to those destructive acts that the art world can’t profit from. (The most startling aspect of Umanets’s naïveté is his failure to understand the difference in value between his signature and the signature of an art-world celebrity.) Vandalism speaks — or spits on, kisses, slashes — the open secret of economic interest.

This is why vandalism that increases dollar value isn’t vandalism. In 1964, Dorothy Podber — a self-described witch and performance artist who had worked at the Nonagon Gallery in Manhattan — visited Andy Warhol’s Factory. Podber asked whether she could “shoot” a stack of his Marilyn paintings. Warhol, apparently believing she meant to photograph the paintings, consented. Podber then removed a pistol and fired at the stack, damaging several canvases.

Podber doesn’t warrant mention as a vandal in Gamboni’s survey, or in the ever-expanding Wikipedia page on art vandalism (maybe I’ll add her), or in any of the compilations of acts of vandalism I’ve seen in the wake of Umanets. Surely she would have made these lists if Warhol had called the cops; instead, after politely asking Podber not to shoot his work again, he simply renamed the canvases: Orange Marilyn became Shot Orange Marilyn, Red Marilyn became Shot Red Marilyn, and so on. Because, and only because, Warhol underwrote the Shot Marilyns, vandalism never occurred. Warhol was the more powerful witch; he made Podber disappear. She gets credit neither as a vandal nor as an artist. In 1989, Shot Red Marilyn sold for $4 million, at that time a record for a Warhol at auction.

When Dinos Chapman was asked to explain how his defacing and displaying Goya’s Los Caprichos etchings was legitimate art, not vandalism, he said: “You can’t vandalize something by making it more expensive” (the Chapman brothers’ “revised and improved” versions of Los Caprichos were selling in 2005 at London’s White Cube gallery for $26,000 apiece). Remember that this was part of Umanets’s and Pinoncelli’s defense — that they were actually increasing the value of the works in question. They are vandals in part because they got the economics wrong in a way that makes the economics plain.

Following Umanets’s attack, there were, understandably, calls for silence: Don’t give the idiot the satisfaction of fame, which will just inspire more vandals; under no circumstances treat him like an artist. (Who knows how many acts of vandalism are never reported by museums? They have an interest in keeping lenders and insurers from thinking of works in their possession as vulnerable to attack.) The desire to strike the name of the vandal from the record has a long history. In 356 b.c., Herostratus burned down the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus with the primary motivation of making himself famous. To prevent copycat acts of vandalism by those seeking immortality, the authorities not only executed the arsonist but, under pain of death, forbade the mention of his name. Needless to say, it didn’t work; Theopompus recorded the event in his Hellenics.

I have no interest in promoting a contemporary Herostratus, in making celebrities out of Umanets and similar figures. But if we ultimately believe a vandal is a vandal and not an artist because he devalues someone else’s property, then art-world radicalism doesn’t look very radical at all. If we believe it’s vandalism because it destroys a thing of beauty as opposed to creating more of it, then many vanguard artists who employ destruction need to be reclassified. The vandal haunts the artist, the art lover, and the art institution because he dramatically acts on what we say but do not mean.

It just so happens that the Tate Britain — a sister of the museum where Umanets attempted to reappropriate a Rothko — has an exhibition entitled Art Under Attack running through next month. It explores attacks on artworks from the Reformation to the present day; the Tate Britain’s director, Penelope Curtis, told the New York Times that the show seems to be making the art world nervous. I was disappointed to learn that the damaged (or by now hopefully restored) Rothko isn’t displayed, but the exhibition does include Metzger, Yoko Ono, and the Chapmans. It acknowledges some of the tenuousness and complexity of the distinction between art and vandalism; nevertheless, I suspect the exhibition is, in more than one sense, still guarded.

What would it mean to think beyond the economics of the art world, to move beyond both vandalism and the market it exposes? Is it possible to get outside the legacy of Duchamp — a legacy that has begotten, whatever Duchamp would have thought of them, Umanetses and Chapmans and Pinoncellis? In 2009, the Polish-born artist Elka Krajewska founded something she calls the Salvage Art Institute (SAI) in New York. The “institute” is basically Krajewska herself. She persuaded the AXA Art Insurance Corporation — one of the largest insurers of art in North America — to give her a sampling of their inventory of “total loss” art. When a work is damaged — in transit, in a fire or flood, in an act of vandalism — and an appraiser agrees with the owner of the work that it cannot be satisfactorily restored, or that the cost of restoration would exceed the value of the claim, the insurance company pays out the total value of the damaged work, which is then, legally speaking, worthless. I always assumed such artifacts were destroyed, but it turns out there are warehouses full of them; Krajewska visited one in Brooklyn. She now possesses more than forty objects that, as far as the art market is concerned, are no longer art.

SAI 0032Materials: ink, paper (3)

Size: 30" × 22" each

Date and nature of damage: unknown, water stained

Date of claim: unknown

Date declared total loss: unknown

Production: unknown

Artist: Robert Arthur Goodnough

Title: lithographs

SAI 0041

Materials: pine

Size: 14" × 14" × 77"

Date and nature of damage: unknown, unknown

Date of claim: unknown

Date declared total loss: unknown

Production: 1989

Artist: William King

Title: Primavera

The first public viewing of the SAI was held at the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery, part of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, last fall. Krajewska, collaborating with Mark Wasiuta, the school’s director of exhibitions, mounted the damaged paintings on movable dollies and also displayed the (heavily redacted) paperwork that detailed the processing of the claims. Some of the damaged works were easily recognizable, such as a small Jeff Koons balloon dog lying in shards on a silver tray. (At Krajewska’s exhibition, you can touch whatever you want; I admit I felt a frisson of transgression getting to handle the fractured sculpture, an icon I have wanted, in my more childish moments, to smash.)

The SAI explicitly positions itself as a kind of conceptual reversal of the Duchampian ready-made. Its mission statement reads:

SAI conceives the declaration that an object is No Longer Art as the symmetrical inversion of the subjective declaration that any object may be art. The signature of the adjuster meets and cancels the signature of the artist.

And Krajewska preempts the possibility of these objects’ being reappraised or resold:

SAI seeks to maintain the zero-value of No Longer Art and recognizes its right to remain independent and divorced from the demands of future marketability.

I had my own experience of something like hyperkulturemia, a feeling of vertigo, when I visited the SAI. What moved me most were not those works that were clearly severely damaged — that had suffered some kind of violence — but those that appeared to me identical to their former incarnation as economically valuable art. For example, to my perhaps unsophisticated eye, several photographs — works by Anne Morgenstern, Rodney Smith, and even Henri Cartier-Bresson — seemed perfectly intact, despite what the owners and appraisers had decided. As I spent a few minutes holding each of these photographs in turn, I remembered the following anecdote from a book by the philosopher Giorgio Agamben:

The Hasidim tell a story about the world to come that says everything there will be just as it is here. Just as our room is now, so it will be in the world to come; where our baby sleeps now, there too it will sleep in the other world. And the clothes we wear in this world, those too we will wear there. Everything will be as it is now, just a little different.

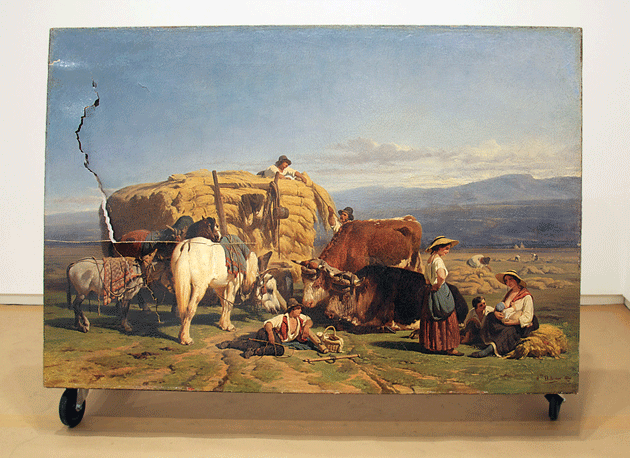

SAI 0016

Materials: oil, canvas

Size: 52" × 35"

Date and nature of damage: March 16, 2010, torn in transit

Date of claim: March 23, 2010

Date declared total loss: March 2010

Production: 1850

Artist: Alexandre Dubuisson

Title: La Moisson

Several of the works in the SAI are just as they were, but a little different. We’re all familiar with material things that take on a kind of magical power as a result of a signature: that’s how branding functions in the gallery system and beyond, whether for Duchamp or Louis Vuitton. But it is incredibly rare to encounter the reversal of that process, to encounter an object freed from the market — freed without being shattered or spit on or torn. It was as if I could register as I held each of the photographs in my hands a subtle but momentous transfer of weight: the market’s soul had fled; it was art outside of capitalism. Each work had been redeemed, both in the sense that the fetish had been converted back into cash, the claim paid out, but also in the more messianic sense of being saved from something, saved for something. For me these objects — just as they were, but a little different — were ready-mades for or from a world to come, a future where there is some other system of value, in the art world and beyond, than the tyranny of price. That’s long been a dream of many artists and vandals alike.