Discussed in this essay:

Updike, by Adam Begley. Harper. 576 pages. $29.99.

The least receptive audience for Adam Begley’s hefty, thorough biography of John Updike may well be other writers. There are certain sentimental tropes about the writing life that writers tend to treasure in order to keep the faith necessary to stay on a career path so generous with discouragements and so parsimonious with rewards: for instance, the notion that rejection builds character. Or that there is some sort of karmic relationship between brutal obscurity and eventual, even posthumous fame — that the latter can be attained only by passing through the moral crucible of the former. What struggling young writer — or bitterly persistent middle-aged writer, for that matter — wouldn’t rather read about the example set by Herman Melville or Emily Dickinson or even John Kennedy Toole than about someone whose career consisted of nothing but unbroken critical and popular success?

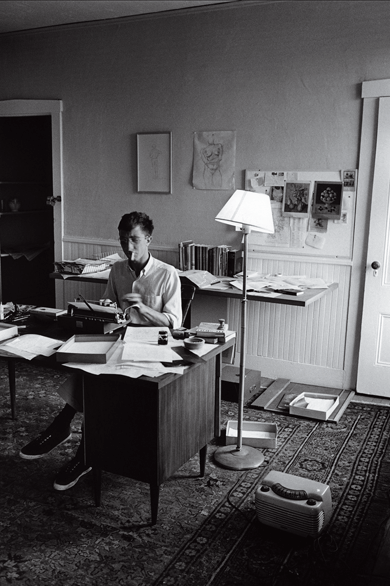

As a boy of twelve, living in rural Pennsylvania, John Updike announced that his life’s ambition was to be a contributor to The New Yorker, and he had closed that deal two months after graduating from college. At Harvard he was denied admission into Archibald MacLeish’s legendary creative-writing seminar, and he died some fifty-six years later without having received the Nobel Prize; but between those two indignities it is fair to say that no conceivable token of the world’s esteem was withheld from him. He had published fourteen books by the time he was thirty-four years old. Two years before that, he became one of the youngest writers ever elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. And so on.

Updike might have thrown the rest of us a bone by experiencing, say, the occasional bout of writer’s block, but no; his great difficulty was that he wrote so much — all of it published — that he could barely keep up with himself. (He once unnervingly admitted, vis-à-vis his side gig as a book reviewer, that he wrote faster than he read.) In the end he produced more than seventy books. One of Begley’s challenges — never mind the challenge of finding some element of suspense in his subject’s “monotonously triumphant career” — is how to keep us interested in the daily life of a man whose existence was relatively dull for the simple, admirable reason that he wrote all the damn time.

Begley puts the smoothness of Updike’s journey in literary context:

Among the other twentieth-century American writers who made a splash before their thirtieth birthday (the list includes Upton Sinclair, Ernest Hemingway, John O’Hara, William Saroyan, Norman Mailer, Flannery O’Connor, William Styron, Gore Vidal, Harold Brodkey, Philip Roth and Thomas Pynchon), none piled up accomplishments in as orderly a fashion as Updike, or with as little fuss. . . . He wasn’t despairing or thwarted or resentful; he wasn’t alienated or conflicted or drunk; he quarreled with no one. In short, he cultivated none of the professional deformations that habitually plague American writers. Even his neuroses were tame.

A biography, unlike virtually every other sort of book, doesn’t always need to justify its own existence. Though the years of Updike’s life were often featureless, in the end he gets a fat biography because he was Great — simple as that. Apart from suffering, Updike did pretty much everything it is popularly thought great writers do. He wrote wryly but affirmatively about sex and God and America; he had a wise, avuncular public face; and every book he wrote was by definition a part of the national cultural conversation. Begley’s stately life of Updike is the logical outcome of our agreement about the institution of Updike’s greatness; ironically, in its reverential thoroughness it contains everything you’d need to arm yourself for that institution’s overthrow.

One couldn’t say Updike was born into his success in any material sense; but his mother — by far the most unsettling figure in this book’s genteel world — made it clear, both to her only child and to the world at large, that she felt from the start that he was destined for adulation. He was raised in Shillington, Pennsylvania, until the family moved, at Linda Updike’s behest, to her own, even smaller hometown of Plowville, a farming community eleven miles away in which Updike felt stifled and deprived. His father, Wesley, was a high school math teacher. They got along well, and, like many sons, Updike admired his dad even while growing aware of the strictures and frustrations of the life he led. But the dominant family relationship — it is an understatement to call it that — was between him and his doting mother, to whose life he apparently gave purpose even before he existed: “I had this foresight,” she once told a journalist, “that if I married his father the results would be amazing.”

Begley (though he does begin the opening chapter with an epigraph from Freud) lays out the evidence of maternal obsession without indulging in a lot of boilerplate psychology; but some future biographer will, you can count on it, and he or she won’t be wrong. “I suppose there probably are a fair number of mothers,” Updike once told Vanity Fair, “who never find completely satisfactory outlets for their sexual energy and inflict a certain amount of it on their male children. Without there being anything hands-on or indecent.” One of Updike’s proposed first novels was about a character named Supermama whose perfection in every respect makes her “insufferable in the eyes of the opposite sex.”

Complicating their Jocasta-complex dynamic, though, was an extraordinary wrinkle: Linda Updike wrote fiction, too. And even though her career was one most authors would envy — she published two books with major publishing houses and ten short stories in her son’s bastion, The New Yorker — he took every opportunity to downplay it, consistently characterizing her, in writings and in interviews, as a “would-be” or “long-aspiring” writer, condemned to “the slave-shack of the unpublished.” Even more galling, she, like Updike (and like, much later, Updike’s son David), often wrote fiction that was transparently autobiographical; so that Updike had, for example, to endure the embarrassment of reading in The New Yorker a short story written by his mother about the end of his first marriage — a subject his own short fiction had previously covered in quite a different tone.

Within hours of leaving him in his dorm room at Harvard, Updike’s mother wrote him a letter from her hotel room across the street, which helps explain why getting out into that wider, more sophisticated world proved such a boon to him. Though he affected ambivalence toward his alma mater, he certainly threw himself into his four years there, graduating summa cum laude while rising to president of the Lampoon. He later summed up his feelings in an instance of the rhetorical move known today as the humblebrag: “I felt toward those [Harvard] years, while they were happening, the resentment a caterpillar must feel while his somatic cells are shifting around to make him a butterfly.”

A talented cartoonist, Updike spent a postgraduate year at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. His ambition at that point, though it didn’t last long, was a telling one: he wanted to become the next Walt Disney. Maximum popularity and a diversity of audience were always inseparable from his idea of artistic success. Around that time he wrote, in a letter to his mother, “We need a writer who desires both to be great and to be popular, an author who can see America as clearly as Sinclair Lewis, but, unlike Lewis, is willing to take it to his bosom.”

In 1955, New Yorker contract in hand, Updike moved to Manhattan, where he lived for a time on the Upper West Side with his new wife, Mary, and the first of their four children. Before long, though, in Begley’s words, “his ambition required him to be a big fish in a little pond.” So in 1957 he moved the family to coastal Ipswich, Massachusetts — to reconnect, he later wrote, with “the whole mass of middling, hidden, troubled America” — and settled for the next two decades into a quiet, small-town life in which he wrote and wrote, taking time off only, it sometimes seems, for adultery, a popular local pastime he turned to account in his 1968 novel Couples, which landed him on the cover of Time and “planted in the public imagination,” as Begley says, “the idea that the adulterous society was territory belonging to him by right of discovery.”

For the rest of his prolific career he toggled between a sometimes fantastic, genre-hopping style (Roger’s Version, S., The Witches of Eastwick, Gertrude and Claudius) and a more purely autobiographical one. The latter was a phenomenon that Begley’s careful cross-referencing throws into amazing relief. The short fiction in particular, with its several stand-ins for the author (Richard Maple, David Kern, Henry Bech), turned into an almost inexhaustible recycling of Updike’s experience. Eight weeks after his divorce hearing he had completed a short story about it. He hired a plumber to fix his leaky pipes and scarcely a month later finished a story called “Plumbing.” His daughter moved to England at age eighteen to live with a man in his thirties (a tortured relationship that ended when the man died of alcoholism at thirty-seven); Updike had completed a short story about her leaving home within weeks. He spent a week sightseeing in Brazil, some of it in a Copacabana hotel room overlooking the beach in Rio, and more or less immediately wrote Brazil, a magical-realist tale of interracial romance that, Begley kindly says, “collected fewer friendly reviews than any other Updike novel.” And then there was the time Updike took a vacation out west with his wife and children, in June; a thinly fictionalized version of it was not just written but also published in The New Yorker that same August. At times it seems almost as if Updike was putting out his own magazine — there is a sense of his meeting some relentless internal quota, of art itself not as a romantic matter of divine inspiration but as a machine that required stoking. It was necessary for him to cannibalize his own experience, whether dramatic or mundane, in order to feed that machine, the way you might eventually have to start burning your furniture if your house got too cold.

It’s lazy to criticize any author’s work on the grounds that there is too much of it. And any number of great artists have given the somewhat chilly impression that their life was there to serve the work and not the other way around. But the speed and accumulation of autobiographical fiction in Updike’s case suggests that he was not interrogating his personal experience so much as ratifying it, consecrating it. He barely changed it. He described his method thus: “truth, slightly arranged.”

If there’s a category-buster in Updike’s vast oeuvre, it’s the tetralogy of Rabbit novels, which on its face is both realistic and nonautobiographical. Updike, in a foreword to the Modern Library collection of these works — which trace the life of a former high school basketball star turned car salesman, from disillusioning, rebellious young adulthood to material success to death — described Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom (I have always hated the condescending obviousness of that last name) as “incorrigible — from first to last he bridles at good advice, taking direction only from his personal, also incorrigible God.” But what strikes one now, reading across Updike’s oeuvre, is how similar Rabbit is, in the end, to Piet Hanema or Richard Maple or Henry Bech or other Updike stand-ins. He trivializes rather than embodies his era’s struggle with expanded freedoms by using them to grant himself moral immunity from the consequences of fucking whomever he likes. Characters don’t have to be likable, of course; but the off-putting aspect of Rabbit, Run isn’t that it’s about a man, worshipped in his youth for his natural talent, who doesn’t question his own droit du seigneur in abandoning his pregnant wife and young child to shack up with a local floozy (whom he treats with contempt) because he is bored; it’s that Updike — who later wrote of the “heavy, intoxicating dose of fantasy and wish-fulfillment” that went into the writing of the novel — proposes that he’s telling a story about America, not a story about Updike.

Begley does an impressive, conscientious job of marshaling evidence of Updike’s many contradictions without ever being the least bit prosecutorial about it. His attitude in general seems proper for a biographer, especially a first one: dutifully skeptical at times, but supportive overall. When forced to call out his subject for behaving badly (for blaming the end of his first marriage on “the human condition,” for instance) or for writing badly (no one could have written as much as Updike did without producing some duds), he does so in a tone not of iconoclasm but of disappointment. He assiduously plows through Updike’s output, always giving his subject the benefit of the doubt while separating the wheat from the chaff. He argues “confidently” that Rabbit Redux is Updike’s strongest novel, which is in line with most critics’ thinking, even if that novel’s depiction of a sexually violent black revolutionary hasn’t aged particularly well. (From the Modern Library foreword: “The rhetoric of social protest and revolt which roiled the Sixties alarmed and, even, disoriented me.”) His one revisionist interpretive choice is to make a case for Updike as a poet; while Begley deserves full marks for bravery and originality, the case is something of a nonstarter. The most you can say about Updike’s poundingly iambic poems, which tend, like the simplest of Frost, toward metaphor as parable —

At night—the light turned off, the filament

Unburdened of its atom-eating charge,

His wife asleep, her breathing dipping low

To touch a swampy source—he thought of death

— is that the best of them aren’t quite as bad as you might have expected them to be.

The poems’ elevation of metaphor, though, is an interesting lens through which to revisit the fiction. Updike wrote self-consciously about big subjects and big themes, but he was always celebrated more for his prose style than for his subject matter. And his great gift, on the level of style, was not just descriptive but explicitly figurative — not about precision, in other words, but about transformation. This gift could work both for him and against him. Figurative language, best employed, is a way of making connections between disparate phenomena, but even more than that it is a way of making us see better, more freshly, more naïvely. Updike was more than capable of such flights:

Outdoors it is growing dark and cool. The Norway maples exhale the smell of their sticky new buds and the broad living-room windows along Wilbur Street show beyond the silver patch of a television set the warm bulbs burning in kitchens, like fires at the backs of caves . . . [A] mailbox stands leaning in twilight on its concrete post. Tall two-petaled street sign, the cleat-gouged trunk of the telephone pole holding its insulators against the sky, fire hydrant like a golden bush: a grove.

But taking one thing and turning it, via language, into another can also be a way of deferring or denying or opting out of engagement with the thing nominally being described. There was that side of Updike’s style, too. When you binge on his work, you start to notice this reflexive opting out, particularly at moments of great feeling —

Since this accident [that killed his parents], the world wore a slippery surface for Piet; he stood on the skin of things in the posture of a man testing newly formed ice, his head cocked for the warning crack, his spine curved to make himself light

— and particularly with regard to women, most egregiously during sex, when they sometimes disappear behind metaphors completely:

Her long body beneath his felt companionable, unsupple, male. His mind moved through images of wood, patient pale widths waiting for the sander, intricate joints finished with steel wool and oil, rounded pieces fitted with dowels, solid yet soft with that placid suspended semblance of life wood retains.

Nearly every time a woman seems aggrieved, Updike retreats into describing her two-dimensionally, figuratively. It’s the alchemy of metaphor, more than character or situation, that seems to justify Rabbit’s walking out on his wife without a scrap of empathetic feeling:

When confused, Janice is a frightening person. Her eyes dwindle in their frowning sockets and her little mouth hangs open in a dumb slot. Since her hair has begun to thin back from her shiny forehead, he keeps getting the feeling of her being brittle, and immovable . . .

It makes him seem like a more interesting and instructive writer, if not necessarily a better one, to understand his profligate gifts not only as a strength but as a weakness.

Updike endured rough relations with some of his children, as well as critical potshots from younger writers, most notably David Foster Wallace in a 1997 New York Observer piece that included a description of Updike as “a penis with a thesaurus.” But such attacks went with, more than threatened, the Olympian territory he occupied. He traveled the world accepting prizes and honors (1981’s Rabbit Is Rich hit the rare trifecta of Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and National Book Critics Circle Award) until his death, from lung cancer, in 2009. Maybe the pithiest late-career anecdote in Updike is the one in which Begley himself unexpectedly and self-deprecatingly appears: in his capacity as an editor at an unnamed magazine, Begley phones Updike at home and asks if he would write for them a little sidebar piece of fluff on the “top five books about loving.” Updike politely inquires further about this classic bit of time-wasting, while in the background the young Begley can clearly hear the excoriating voice of Updike’s second wife, Martha, telling her husband to say no, to hang up the phone.

Updike did not say no very often, to anything, not even when he clearly could or should have. It wasn’t a simple matter of his being a nice guy. He needed to accommodate. When lawyers at Knopf asked that Rabbit, Run be trimmed of some material that might potentially be considered libelous, Updike excised every detail suggested. He “rapidly” agreed to the cuts on entirely hypothetical grounds of obscenity, observing later that “none of the excisions really hurt.” (Despite which he had the gall to write condescendingly, in some of the Bech stories, about writers in Eastern Europe who risked real consequences for defying authority.)

He delayed the publication of Marry Me for twelve years rather than risk the potentially costly wrath of the “barely fictionalized” figures — his then wife and his then mistress — on whose experience it was based. When Martha’s ex-husband threatened to sue Updike if he ever wrote about his new stepkids, Updike complied without hesitation. (He continued to write with merciless obviousness about the rest of his family, children included.)

Updike admitted to tailoring his work to the objections of his few critics; stung by his late-career tarring as a misogynist, he responded by writing a novel with three strong female protagonists. That they were also witches did not exactly strengthen his case. When his government asked him to travel abroad on its behalf, to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, he did so gladly. He was patriotic without being political.

One rare instance of his saying no — bravely, it must be conceded — was when he was asked to express opposition to the Vietnam War, which in fact he supported. He didn’t see why, as a clear force for good, we shouldn’t be in Vietnam, though of course if we were asked to leave by our hosts it would be only proper to do so. “I distrusted orthodoxies,” he wrote, “especially orthodoxies of dissent.”

But in truth Updike was a Will Rogers for his politically contentious age: he never met an orthodoxy he didn’t like. His life consisted of saying yes to everything, and of questioning nothing — of accepting, and eventually being incorporated into, the dominant public narratives of his era. To say that he was some sort of sexual outlaw is a canard; he knew what sort of “obscenity” would get you tried in court and what sort would get you the cover of Time.

While it’s hard to hold Updike accountable for attitudes typical of his generation, the fact is that he did not handle notions of otherness very well at all, from his Chinese-coolie cartoons for the Lampoon (“Why shouldn’t we work for coolie wages?”), to his attempts to amuse his children with blackface routines, to a description in Roger’s Version of an unnamed black girl in an abortion clinic as “princess of a race that travels from cradle to grave at the expense of the state, like the aristocrats of old,” to perhaps his most disastrous outing, the 2006 novel Terrorist. His feeling for outsiders was best captured in his description of the chief allure of belonging to clubs like the Lampoon: “the delicious immensity of the excluded.”

For a useful contrast to this approach to privilege, one needn’t look any further than Updike’s freshman dorm room at Harvard. His roommate was the future cultural historian Christopher Lasch, whose feelings toward the status quo were well encapsulated by the title of his landmark book, The Culture of Narcissism. Lasch (known in his college days as “Kit”) could have taken a path that sanctified his place at the top of the social pyramid but chose instead to define himself via opposition to it, to critique the America that his former roommate wanted to “take to his bosom.” Lasch and Updike drifted apart after college, but even before then, Lasch’s eye was pretty contrary: “He is more industrious than I,” he wrote home, “but I think his stuff lacks perception and doesn’t go very deep.”

The great defect in Updike’s artistic makeup had to do not with suffering but with critical thinking. Begley calls him the “poet laureate of American middleness,” but that’s not quite it. Updike was the bard of the world as he found it. The more that world esteemed him, the more conservative his love of it became. “We took the world as given,” he wrote in a 1973 essay called “Apologies to Harvard.” “We did not know we were a generation.” His greatness, like America’s, was a matter of predestination. The relationship was symbiotic. “Only in being loved,” he wrote, “do we find external corroboration of the supremely high valuation each ego secretly assigns itself.”

The Rabbit tetralogy is usually considered the apex of Updike’s achievement. Updike wrote that the invention of Harry Angstrom was for him “a ticket to the America all around me,” which is to say the America of the Fifties, Sixties, Seventies, and Eighties. Here is how the life of that invention ends, as Rabbit’s heart gives out:

Harry’s eyes burn and the impression giddily — as if he has been lifted up to survey all human history — grows upon him, making his heart thump worse and worse, that all in all this is the happiest fucking country the world has ever seen.

Begley’s psychological portrait — never judgmental, relentlessly thorough — makes it easier to fathom how an American writer could have lived through those times and come to that conclusion. The institutional love in which Updike basked is in fact no mystery; in every age, in every regime, artists are rewarded for doing what he did.