Neuroscientists who work on the human brain seldom mention free will. Most consider it a subject better left, at least for the time being, to philosophers. Meanwhile, their sights are set on discovering the physical basis of consciousness, of which free will is a part. No scientific quest is more important to humanity. Everyone — scientists, philosophers, and religious believers alike — can agree with the neurobiologist Gerald Edelman that “[c]onsciousness is the guarantor of all we hold human and precious. Its permanent loss is considered equivalent to death, even if the body persists in its vital signs.”

The physical basis of consciousness won’t be an easy phenomenon to grasp. The human brain is the most complex system, either organic or inorganic, known in the universe. Each of the billions of nerve cells (neurons) composing its functional part forms synapses and communicates with an average of ten thousand others; each launches messages along its own axon pathway using an individual digital code of membrane-firing patterns. The brain is organized into regions, nuclei, and staging centers that divide functions among them. These regions respond in different ways to hormones and sensory stimuli originating from outside the brain, while sensory and motor neurons all over the body communicate so intimately with the brain as to be virtually a part of it.

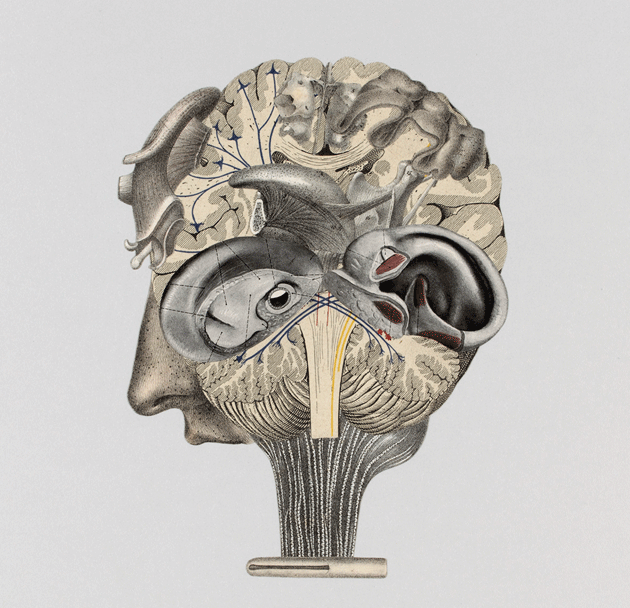

Untitled, a collage on paper by Frederick Sommer. Courtesy the Frederick & Frances Sommer Foundation and Bruce Silverstein, New York City

Of the 20,000 to 25,000 genes in the human genome, half participate in some manner in the prescription of the brain-mind system. This amount of commitment has resulted from the most rapid evolutionary change known in any advanced organ system of the biosphere. It entailed a more than twofold increase in brain size across 3 million years, from 600 cubic centimeters in the australopith prehuman ancestor to 900 cubic centimeters in Homo habilis, thence to about 1,400 cubic centimeters in modern Homo sapiens.

Philosophers have labored for more than two thousand years to explain consciousness. Innocent of biology, however, they have for the most part gotten nowhere. I don’t believe it too harsh to say that the history of philosophy when boiled down consists mainly of failed models of the brain. A few contemporary neurophilosophers, such as Patricia Churchland and Daniel Dennett, have made splendid efforts to interpret neuroscience research as it has become available. They have helped to demonstrate, for example, the ancillary nature of morality and rational thought. Others, especially those of poststructuralist bent, are more retrograde. They doubt that the “reductionist” or “objectivist” program of brain researchers will ever succeed in explaining the core of consciousness. Even if it has a material basis, subjectivity in this view is beyond the reach of science. To make their argument, the mysterians (as they are sometimes called) point to the qualia — the subtle, almost inexpressible feelings we experience about sensory input. For example, “red” we know from physics, but what are the deeper sensations of “redness”? And if we can’t answer that, then what can scientists ever hope to tell us on a larger scale about free will or about the soul?

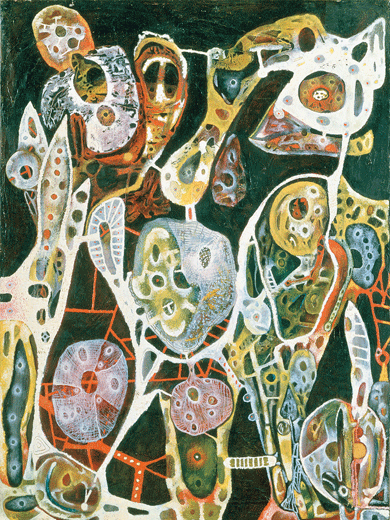

Cerebral Landscape, a painting by Charles Seliger. Collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alexis Zalstem-Zalessky. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York City

Neuroscientists, to their credit, have no illusions about the difficulty of the task. They agree with Darwin that the mind is a citadel that cannot be taken by frontal assault. They have set out instead to break through to its inner recesses with multiple probes along the ramparts, opening breaches here and there; by technical ingenuity and force they hope to enter and explore wherever they find space to maneuver.

You have to have faith to be a neuroscientist. We don’t know where consciousness and free will may be hidden — assuming they even exist as integral processes and entities. Meanwhile, neuroscience has grown rich, primarily because of its relevance to medicine. Its research projects are growing on budgets of hundreds of millions to billions each year (in the science trade it’s called Big Science). The same surge has occurred in cancer research, in designing the space shuttle, and in experimental particle physics.

Perhaps, then, a direct assault is possible after all. The Brain Activity Map (BAM) Project, led by the National Institutes of Health, has the goal of generating a map of the activity of every neuron in real time. The program, if successfully funded, will parallel in magnitude the Human Genome Project. Much of the technology will have to be developed on the job.

The basic goal of activity mapping is to connect all of the processes of thought — rational and emotional; conscious, preconscious, and unconscious; held still and moving through time — to a physical base. It won’t come easy. Bite into a lemon, fall into bed, recall a departed friend, watch the sun sink beyond the western sea. Each episode comprises mass neuronal activity so elaborate we cannot even conceive of it, much less write it down as a repertory of firing cells.

Assuming that BAM or another, similar enterprise is successful, how might it solve the riddle of consciousness and free will? I believe that the solution will come relatively early, rather than as a grand finale when the map is complete. There are several reasons for optimism. First, the increase in brain size leading up from the habiline prehumans to Homo sapiens suggests that consciousness evolved in steps, similar to the way other complex biological systems developed — the eukaryotic cell, for example, or the animal eye, or colonial life in insects.

It should then be possible to track the steps leading to human consciousness through studies of animal species that have come partway to the human level. The mouse has been useful in early brain-mapping research and will continue to be productive. This species has considerable technical advantages, including convenient laboratory rearing (for a mammal) and a strong supporting foundation of prior genetic and neuroscientific research. A closer approach to the actual sequence can be made, however, by studying humanity’s closest phylogenetic relatives among primates, from lemurs and galagos at the more primitive end to rhesus macaques and chimpanzees at the higher end. The comparison would reveal which neural circuits and activities were attained by non-human species, when they attained them, and in what sequence. That data could help us determine which neurobiological traits are uniquely human.

The second point of entry into the realm of consciousness and free will is the identification of emergent phenomena — entities and processes that come into existence only with the joining of preexisting entities and processes. They will be found, if the results of current research are indicative, in the linkage and synchronized activity of various parts of both the sensory system and the brain.

The nervous system can be usefully conceived as a superbly well-organized superorganism built on a division of labor and specialization in the society of cells — around which the body plays a primarily supportive role. An analog, if you will, is to be found in a queen ant’s or termite’s relationship with her supporting swarm of workers. Each worker on its own is relatively stupid. It follows a program of blind, untutored instinct, which is subject to only a small amount of flexibility in its expression. The program directs the worker to specialize in one or two tasks at a time and to change programs in a particular sequence — typically nurse to builder or guard to forager — as it ages. All the workers together, however, are brilliant. They address all needed tasks simultaneously and can shift the weight of their effort to meet potentially lethal emergencies, such as flooding, starvation, and attacks by enemy colonies.

The superorganism that is our brain also takes advantage of the narrowness of the range of human perception. Our sight, hearing, and other senses impart the feeling that we are aware of almost everything around us in both space and time. Yet we are aware of only minute slivers of space-time, and even less of the energy fields in which we exist. The conscious mind is a map of our awareness of the intersections of those parts of the continua we happen to occupy. It allows us to see and know those events that most affect our survival in the real world — or, more precisely, the real world in which our prehuman ancestry evolved. To understand sensory information and the passage of time is to understand a large part of consciousness itself. Advance in this direction might prove easier than previously assumed.

“Untitled,” a photograph with stitching and pencil drawing by Keith Smith. Courtesy the artist and Bruce Silverstein, New York City

The final reason for optimism is the human necessity for confabulation, which offers more evidence of a material basis to consciousness. Our minds consist of storytelling. In each instant, a flood of information flows into our senses, more than the brain can process. To augment the fraction of this information, we summon the stories of past events for context and meaning. We compare the past and the present and apply the decisions that were made previously, variously right or wrong. Then we look forward, creating — not just recalling this time — multiple competing scenarios. These are weighed against one another by the suppressing or intensifying effect imposed by aroused emotional centers. A choice is made in the unconscious centers of the brain, recent studies tell us, several seconds before the decision arrives in the conscious part.

Conscious mental life is built entirely from confabulation. It is a constant review of stories experienced in the past and competing stories invented for the future. By necessity, most conform to the present real world. Memories of past episodes are repeated for pleasure, for rehearsal, for planning, or for various combinations of the three. Some of the memories are altered into abstractions and metaphors, the higher generic units that increase the speed and effectiveness of the conscious process.

Most conscious activity contains elements of social interactions. We are fascinated by the histories and emotional responses of others. We play games, both imaginary and real, based on the reading of intention and probable response. Sophisticated stories at this level require a big brain housing vast memory banks. In the human world, that capacity evolved long ago as an aid to survival.

If consciousness has a material basis, can the same be true for free will? Put another way: What, if anything, in the manifold activities of the brain could possibly pull away from the brain’s machinery to create scenarios and make decisions of its own? The answer is, of course, the self. And what would that be? Where is it? The self does not exist as a paranormal being living on its own within the brain. It is, instead, the central dramatic character of the confabulated scenarios. In these stories, it is always on center stage — if not as participant, then as observer and commentator — because that is where all of the sensory information arrives and is integrated. The stories that compose the conscious mind cannot be taken away from the mind’s physical neurobiological system, which serves as script writer, director, and cast combined. The self, despite the illusion of its independence created in the scenarios, is part of the anatomy and physiology of the body.

The power to explain consciousness, however, will always be limited. Suppose neuroscientists somehow successfully learned all of the processes of one person’s brain in detail. Could they then explain the mind of that individual? No, not even close. It would require opening up the immense store of the brain’s particular memories, both those images and events available to immediate recall and those buried deep in the unconscious. And if such a feat were possible, even in a limited way, its accomplishment would modify the memories and the emotional centers that respond to those memories, causing a new mind to emerge.

Then there is the element of chance. The body and brain are made up of legions of communicating cells, which shift in discordant patterns that cannot even be imagined by the conscious minds they compose. The cells are bombarded every instant by outside stimuli unpredictable by human intelligence. Any one of these events can entrain a cascade of changes in local neural patterns, and scenarios of individual minds changed by them are all but infinite in detail. The content is dynamic, changing instant to instant in accordance with the unique history and physiology of the individual.

Because the individual mind cannot be fully described by itself or by any separate researcher, the self — celebrated star player in the scenarios of consciousness — can go on passionately believing in its independence and free will. And that is a very fortunate Darwinian circumstance. Confidence in free will is biologically adaptive. Without it, the conscious mind, at best a fragile, dark window on the real world, would be cursed by fatalism. Like a prisoner serving a life sentence in solitary confinement, deprived of any freedom to explore and starving for surprise, it would deteriorate.

So, does free will exist? Yes, if not in ultimate reality, then at least in the operational sense necessary for sanity and thereby for the perpetuation of the human species.

Excerpted from The Meaning of Human Existence, by Edward O. Wilson. Copyright © 2014 by Edward O. Wilson. With permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.