Denis Johnson’s heart beats for the lowlifes and fuck-ups, drunks and speed freaks, the losers who are on their last score and the scavengers feeding on the edges of foreign wars. His failures have a way of talking like poets, and, once in a while, they commit acts of grace. In the short story “Emergency,” from the 1992 collection Jesus’ Son, a man shows up at the hospital with a hunting knife lodged in one eye. While the doctors stand around worrying, a doped-up orderly named Georgie goes into the OR and comes out with the blade in his hand. Everything’s okay: vitals normal, reflexes check out. “There’s nothing wrong with the guy,” a nurse says. “It’s one of those things.” At the end of the story, an AWOL soldier trying to hitchhike to Canada asks Georgie what he does for a living. “I save lives,” he says. When Jesus’ Son was turned into a movie, Johnson played the guy with the knife — Jesus would have called it a beam — in his eye. This could be a comment on the nature of authorship, although something tells me that he just thought it was funny.

Johnson’s newest is The Laughing Monsters (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $25), a thriller narrated by Roland Nair, a spy of indeterminate nationality who has been sent by NATO intelligence to Sierra Leone to meet up with his old buddy Michael Adriko. Michael is a handsome, graceful ex–child soldier currently AWOL from a U.S. Special Forces unit commanded by the father of Davidia St. Claire, his fiancée. (Johnson has never been much for female characters, and gorgeous Ph.D. dropout Davidia is the only false note in this plausibly improbable chain of events.) Nair is supposed to be collecting intel on Michael, but instead Michael enlists him in a deal that involves selling phony uranium to the Mossad.

Nair is a drunk. He’s also something of an amateur anthropologist. He, Michael, and Davidia catch a flight to Kampala, where they board a crowded bus to Arua. The passengers

smelled of liquor and urine and armpit. Michael now placed himself among them, resuming the mantle of African poverty — the way a civilized African does, relaxing the shoulders and calming the hands and letting down the veil over his heart.

The bus’s woman conductor stood in the aisle and addressed us, giving us her name and town and then bowing her head to pray out loud for one full minute in the hope this journey wouldn’t kill us all. She invited everyone to turn to the next passenger and wish him or her the same thing, and we did, fare ye well, may this journey not be your last, although one of those journeys, surely, will send us — or whichever parts of us can be collected afterward — to the grave.

The grave threatens to open more than once. In the market in Arua, Michael and Nair show two South African middlemen the bogus uranium. One of the South Africans pulls a knife, and Nair stands by, useless, as Michael is stabbed to the bone. Undaunted, the trio sneak into the Democratic Republic of the Congo; the plan is for the happy couple to wed in Michael’s ancestral village on New Water Mountain. This optimistic itinerary is delayed, first by the Congolese army, then by the Green Berets. “There’s no sense calling it a mess until we see how it all turns out,” Nair writes to his girlfriend. “Sometimes you just get stuck. That’s Africa. Then you’re on your way again without any idea what happened, and that’s Africa too.”

On the mountain, Nair meets a white missionary who explains that Michael’s village is refusing a medical evacuation. The new water is toxic, but the village’s queen — a buzz-cut lunatic named La Dolce who rules from a wooden chair that dangles from the treetops — won’t let them go. Nair arrives in time to see Michael attempting a coup by hacking at La Dolce’s throne with a machete, but the rebellion only seems to make her stronger. Nair can’t get home without Michael, so he spends the night passing a gourd of fermented plantain and sugar cane with three cattle herders who “have the puffy look of corpses floating in formalin.” Davidia has long since gone home.

Like Nobody Move, Johnson’s last book, The Laughing Monsters is a quick-and-dirty genre read. (He’s been blowing off steam ever since conquering the quagmire of the 600-page Tree of Smoke in 2007.) But while Nobody Move was all zingers and grindhouse fun, The Laughing Monsters echoes with real violence and despair. One can’t help but recall Johnson’s own frustrated, terrified reportage from Liberia’s civil war. He crossed paths with the small boys’ unit. He tried to bribe the wrong people. A man being tortured begged him for his life. He met Charles Taylor. But by the time all that happened, Johnson had long since unraveled. It was the sheer impossibility of getting a simple ride across the border that did it. “My parents raised me to love all the earth’s peoples,” he wrote. “Three days in this zone and I could only just manage to hold myself back from screaming Niggers! Niggers! Niggers! until one of these young men emptied a whole clip into me.” Before The Laughing Monsters ends, Nair calls Michael the same name. It spumes like lava, the last desperate gasp of uncomprehending white panic.

The rough sentimentality Johnson often has at his disposal is missing from these pages. I won’t say whether Nair and Michael make it down from New Water Mountain alive. It hardly matters. Johnson’s characters have found something like salvation in the prefab pits of Phoenix and up the California coast, and even, perversely, in the jungles of Vietnam. In Africa, though, the most they can do is cheat death.

In the late Nineties, after a tour as a tank commander in Desert Storm, a West Point graduate named John Nagl went to Oxford to write his dissertation. Most military professionals were riding high on the victory in Iraq, studying peacekeeping or planning for the Future Combat System, a proposed set of vehicles that would allow firing on the enemy from greater range. Nagl wasn’t convinced. “The rest of the world had seen the ease with which America’s conventional military forces cut through the Iraqi military,” he thought. “They would have been crazy to fight us that way again.” He turned to counterinsurgency, researching the British victory in Malaysia and comparing it to the American mess in Vietnam. His work was ignited by a quote he found by T. E. Lawrence that “war upon rebellion was messy and slow, like eating soup with a knife.”

Nagl devoted the next twenty years to teaching the Pentagon table manners. “Eating Soup with a Knife” inspired the title of his dissertation and his intellectual rallying cry. Knife Fights: An Education in Modern War (Penguin Press, $27.95) is the story of his career and an intellectual genealogy of contemporary counterinsurgency doctrine. He experienced the soup firsthand in Al Anbar province in 2003, where he and his unprepared men taught themselves how to make inroads with Iraqi police and gain the tatters of trust from locals. (The Army hadn’t updated its counterinsurgency manual since Vietnam.) Nagl wasn’t allowed to drop cash for information, so instead he dropped napkins; the informants picked them up and were paid for trash collection.

Knife Fights, however, isn’t a war memoir. It’s a window into how the Pentagon thinks and, crucially, how it — slowly — changes its mind. The military is an intellectual class as well as a war-making machine, and Nagl tracks counterinsurgency as it finally, through panels and dissident journals, breaks through. Around the time that he contributed to General Petraeus’s new field manual, Nagl heard Condoleezza Rice on the radio advocating the counterinsurgency mantra of “clear, hold, and build” before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He pulled his car off the road to cry.

Counterinsurgency doctrine has been necessary to all empires, of course, though it used to be a rather more straightforward matter. Nagl reminds us that

when the Romans confronted a rebellious province, they would first build a road to it, then methodically slaughter the men and boys in sector, sell the women and children into slavery and salt the fields so that nothing would grow. It was an effective counterinsurgency technique . . . but this technique was obviously not a viable option in an era ruled by CNN and the Geneva Convention.

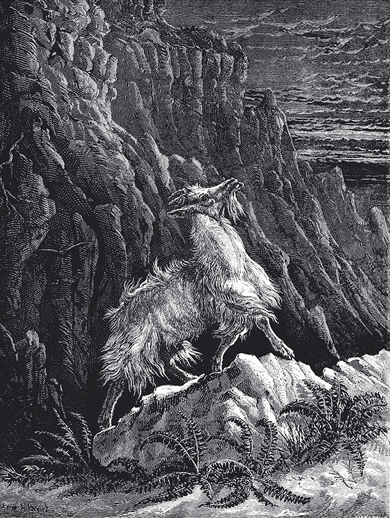

Karen Armstrong’s Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence (Knopf, $30) opens with the story of the scapegoat — the animal that the Jewish high priests made the symbolic bearer of all the people’s sins, before releasing it to die outside the city gates. She writes that today religion itself acts much like this scapegoat did, bearing the blame for all manner of brutishness and persecution. Armstrong is a former nun who has published more than twenty books on the Abrahamic traditions, and she often writes on compassion, tolerance, and interfaith dialogue. In Fields of Blood she argues that it is the agrarian state, and not any conception of the divine, that is the root of bloodshed. She returns often to the story of the emperor Ashoka, who ruled an Indian empire between 268 and 223 b.c. “Appalled by the suffering his army had inflicted on a rebellious city, he tirelessly promoted an ethic of compassion and tolerance but could not in the end disband his army. No state can survive without its soldiers.”

The idea that religion causes violence is too shallow by half, but it’s doubtful that this book will win many converts to its worthy cause. A history of violence may be too much history. Armstrong covers ancient India and China; the dawn of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam; the Crusades; the Hundred Years’ War; the Thirty Years’ War; the French Revolution (during which the state became the religion); and contemporary jihad. There’s a brief spin through Puritan colonies in New England, a few paragraphs on Partition, as well as the Inquisition, the American Revolution, and all of ancient Mesopotamia. It’s a grueling march of names, dates, and battles, brightened by the occasional trivium. Did you know that in the wars of the eleventh century, the Chu “bullied” their enemies with “acts of outrageous kindness” like throwing pots of wine over battlements and walls? “When a Chu archer used his last arrow to shoot a stag that was blocking his chariot’s path, his driver immediately presented it to the enemy team that was bearing down upon them. They at once conceded defeat, exclaiming: ‘Here is a worthy archer and well-spoken warrior! These are gentlemen!’ ”

Armstrong is at her most persuasive when she argues against separating religion from politics at all, but this notion falls away around the sixteenth century, when Martin Luther established religion as a separate sphere of faith rather than a set of customs that suffused the world. Sometimes Armstrong holds on to a definition of religion as social practice; sometimes she writes about it as a matter of belief; sometimes she talks about the “real” meaning of sacred texts. It all gets a bit woolly. As corrupt as religious institutions have been, Armstrong clearly prefers them to secular ideologies, which are “less adept than the ancient religions at helping people face up to the grimmer realities of human existence for which there are no easy answers.” That humans are naturally prone to violence she chalks up to our “reptilian brain,” which hardly gives us credit for our creativity. I’ve never seen a lizard with a knife in its eye.