“Welcome to my office!” Bob Matthews shouts with a smile part friendly and part crazy. We are near Rabideau Lake just off the Leech Lake Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota. It’s late August, the pinecones coming in, and Bobby has taken me out for white spruce cones. We each carry a five-gallon bucket, a shallow white Tupperware tray, leather gloves with the fingers cut off, and a tube of Goop. The Goop is so the cones won’t stick to our fingers and slow us down. Bobby’s about to say something else when we hear a pickup rumbling over the washboard road. “Get in the woods,” he calls, before diving into the trees.

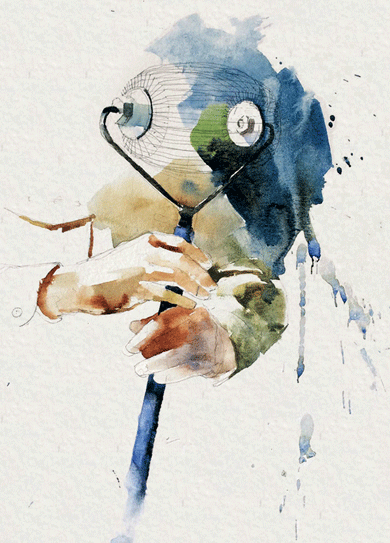

12:20 p.m., crossing a meadow to a small lake to set leech traps. Illustrations from the Leech Lake Indian Reservation by Stan Fellows

These northern Minnesota woods, once virgin white pine with an understory of spruce and birch, have been logged many times since the timber boom of the late nineteenth century. In place of the sterile majesty of old growth is a wild patchwork of birch, jack pine, Norway pine, poplar, and spruce in the uplands and ash, basswood, elm, ironwood, sugar maple, and tag alder in the lowlands. The whole region is scrubby, dense, in places impassable, united by vast swamps and slow-draining creeks, rivers, and lakes. The land — desolate in winter, indescribably uncomfortable in summer — is easy enough to love in the abstract. Up close there is a roughness to it. The spruce grow close together and block out the sun. The forest floor is dun, and the varicose roots stick out of the soil.

Bobby finds crescent-shaped cones about an inch and a half long. He drops to his knees to pick them off the ground, putting them into his tray with astonishing speed. The cones rattle in his tray until it’s full, and they rattle again as he empties the tray into his bucket. To me it sounds pleasant. To Bobby it sound like money.

You’d hear Bobby’s name whispered a lot when I was growing up on the Leech Lake Reservation. Who had the best rice? Who had the most? Who knew where the best boughs were for picking? Who was the damnedest trapper in northern Minnesota? At funerals and picnics and feasts and Memorial Day services, when talk turned to hunting or trapping or general woodsiness, Bobby was always mentioned as the best. I think of Bobby whenever a new book or movie or magazine article comes along urging a back-to-the-land movement as a cure for what ails America. Nostalgia for a direct, uncorrupted relationship between people and the animals and plants that sustain us may be as old as civilization itself, and it cycles into and out of fashion, but it seems particularly potent in times of economic crisis, when people respond to want with a Thoreauvian “simplify.” Such times bring forth a familiar set of precepts (nuanced, inflected, but there all the same): nature does it best; living off the land is healthier; we need to return to the Earth Mother; we should find and collect rather than modify and improve; instead of conquering the wild we need to conquer our own insistence on improving on nature’s offerings and design. Hidden in this reorientation is the idea — sometimes explicit and sometimes merely notional — that perhaps American Indians had it right all along. The Indian way of life, and activities such as hunting and gathering that are coded as Indian, are healthier and more sustainable. What I hear in these narratives is the persistent notion that American Indians and our associated lifestyles are not just more authentic or noble but more practical.

Meanwhile, things at Leech Lake — home to more than 9,000 Ojibwe Indians, including much of my family — aren’t so bucolic. While the rest of the world tries to starve itself back into shape, nearly half the reservation lives below the poverty line, with unemployment as high as 60 percent, little to no infrastructure, few entitlements, a safety net that never was, no industry to speak of, and a housing crisis that has been dire not for five years but since the reservation’s founding in 1855. On Leech Lake, subsistence — living off the land — is a way of life for many, though it doesn’t look the way it does in the popular imagination.

Hunting, gathering, subsistence living — not as an experiment to curb the excesses of the modern way of life, but as its own way — is often thought to have died out in North America around the time the American bison was largely exterminated and most tribes wound up on reservations. I went back to Leech Lake to see whether that’s true. I knew that if I wanted to learn what subsistence really looked like, I had to find Bobby Matthews.

Bobby is not that tall, maybe five foot eight, but he has the arms and shoulders of a much larger man. His hair is thinning and gray, pulled back in a ponytail. He shaves once a year, on his birthday. His eyes are powerful and deeply set. His voice, calm in one moment, will rise to a shout in the next. He speaks rapidly and has the habit of always using your name when he speaks to you. (On the phone: “Hey, it’s Dave.” “How’s David doing?”) Many of his comments begin with “So I says, ‘Look here.’ ” As in: “So, Dave, so the guy says to me, ‘Where’d you get all those leeches, Bob?’ And Dave, I says to him, ‘Well, look here, goddamnit, I got ’em in the getting place, that’s where.’ ” He laughs a lot, but under all his energy and excitement there is the threat of violence. It is the deep violence of the tribe: there if necessary but usually held in check. There is something about him that remains thoroughly undomesticated. But there is something else in him, too: a real curiosity about how all of it (“it” being the woods) fits together. He is plagued by wonder.

“I begin each day like this, Dave. I get up at 4:30 and I turn on the coffee and I throw one of those rice bags you get at the drugstore in the micro. When the coffee and the rice bag are done, I sit in my chair and drink my coffee and heat up my back a little and smoke a joint and look at my books. I look at my books, Dave, going back five, ten, fifteen years. I keep notes on everything I see. The temperature. The barometric pressure. Where is the wind coming from? What little flowers — I don’t even know what they’re called — are in bloom, and how many leaves are on the trees? I keep track of all this stuff in my books, Dave. So I can know the patterns. So I can compare one year to the next. When I’m done smoking I head out and get to work. I’m out the door by 5:30.”

Bobby’s life follows a seasonal cycle. In the spring and early summer he traps leeches. Late summer he begins picking pinecones and then stops to harvest wild rice. When the wild-rice harvest is done he goes back to pinecones. After cones comes hunting and trapping. After the ground is frozen hard he goes out in the swamps to cut cranberry bark. By the time that’s all done he starts leeching again. It’s hard to say how many people live this way — hunting, trapping, and harvesting their way through the seasons — because records aren’t kept for many of these activities. Some harvests are for consumption only — like hunting. There is no official market for game (it has been against the law to sell game since the early ninetenth-century). Commercial fishing is also restricted, though black markets do exist for meat and fish. Most everything else is officially for sale. The state of Minnesota keeps good records on killing and poor records on gathering, with the exception of wild rice: the number of ricing licenses issued each year by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has fallen from an average of more than 10,000 in the Sixties to around 1,000 today. More than half of all ricers who buy licenses are older than fifty. Harvesting wild rice is arguably the most efficient, easiest way to stock your larder with a supremely nutritious source of food, yet the art and practice are dying out.

The DNR sells several thousand trapping licenses each year, but a quarter of those who buy licenses don’t trap any animals, and judging from the trappers I know, few make any real profit. As for harvesting bait (mostly leeches and minnows), a few hundred bait-harvest licenses are sold in Minnesota annually. There are no licenses required for many of the principal subsistence activities in the north. Cutting balsam and cedar boughs for wreaths, harvesting pinecones, cutting cranberry bark — all of these activities are unregulated, so no one really keeps track. From what I can tell by talking to bough, bark, and cone buyers, there are quite a few casual harvesters, those who do it for pocket money when they get the chance or are out of a job, or as a sunny afternoon activity with their kids in the woods. In all, there might be a few thousand casual hunter-gatherers (more like hobbyists), a few hundred who spend most of their time living off the land, and a proud few like Bobby Matthews who do it exclusively.

Bobby sells his cones to an outfit called Cass Lake Tree Seed, which extracts the seeds to sell to the U.S. Forest Service and sells the dried cones to craft stores like Michaels. Cass Lake’s owner, Rick Baird, buys cones from around fifty different pickers, most of whom are Indian. “Pickers run the range,” he told me. “Some people come in with half a bushel. I write them a check for fifteen dollars. Bob Matthews is one of the best pickers. I don’t write him many fifteen-dollar checks. He brings in five hundred dollars’ worth of cones at a time. No one knows the woods like Bobby.” Baird’s best pickers can make around $5,000 for the season, and he’s confident that more people could make that kind of money. “If a guy wanted to start picking he might get skunked in the beginning — he wouldn’t know where to go or what was in season — but after he got the hang of it he could make fifty dollars a day without working too hard.”

After about half an hour we have picked a little less than a bushel. We stand and stretch before separating to look for more. Another hour passes. Bobby shouts and we meet back at the truck. He dumps all the cones in a tub. “One even bushel. That’s thirty bucks, Dave. Two hours, two guys, and maybe twenty dollars in gas. We broke even. But if you really get into the cones and you pick steady all day, a guy can clear maybe fifty to eighty dollars, depending on the type of cone.” Spruce are paying thirty, Bobby says. Norway pine and white pine, a little less. Black spruce pay around fifty, but they won’t be ready till late fall. “The Forest Service was buying oak last year. So Julie and I are driving around, looking for oak trees. You ever try to find a bunch of acorns underneath all the leaves and brush and whatnot? It’s not easy, Dave! And so I says to Julie [his wife], ‘Come on, this is a waste of time,’ and I drive over to the cemetery and find the caretaker, and I says to him, ‘Hey! Let me borrow your rake.’ ‘What for?’ he says. ‘I’m gonna rake your cemetery for you,’ I tell him. You know the nice thing about cemeteries? Let me tell you: no leaves! We made, I’d have to check my books to say exactly how much, but I think last year we made about five thousand on acorns alone.”

After we’re back in the truck, Bobby and I go to Rabideau Landing to check on the rice. The heads are nowhere near full. Bobby lights up a joint. He gets contemplative. “You know, Dave. The creator or God or whatever you call it made the universe and all the beings in it and put this tree here and that bush there, and he made the beavers and the deer and the plants that are good to eat and the ones that are good for medicine. He made all of it, and it is beautiful! And I look out over that creation and sometimes I don’t see it like other people do. I look out at all of it, and what I see is money. And by God I am going to find a way to liberate it out of there.”

Much of what Bobby knows he learned from his father and grandfather. Bobby’s father, Howard, was one of seven kids born to Izzie Matthews in Bena, Minnesota, on the Leech Lake Reservation. Izzie was a full-blooded Ojibwe. Her husband, Harris Matthews, was a lumberjack, bar owner, and bootlegger, originally from Chicago. He wore an eyepatch and drove a Model A. By all accounts, he’d try anything to make a buck. He’d rice. He’d bootleg. He trapped on ice skates because it was faster. Howard and his brothers and sisters grew up fending for themselves. Most of them were sent to Tomah Indian Boarding School in Tomah, Wisconsin, where they spoke in English and fought Ho-Chunks. By the time Bobby, Mikey, Jimmy, Lynette, and Shelley were born, their father had inherited Harris Matthews’s roving, hard-driving, not entirely legal way of putting money in his pocket and bread on the table. Bobby remembers that Howard would cut pulp by hand and that when Bobby and Mikey got home from school they’d put down their bags and go out in the woods and help him and their mother, Betty, peel and stack the logs. In the summer they all traveled to Ray, Minnesota, near the Canadian border, to pick blueberries.

When he was eighteen Bobby and his cousins broke into summer cabins, mostly for the whiskey and beer. Near Judd’s Resort on Lake Winnibigoshish they broke into a cabin, and on his way out Bobby grabbed an old shotgun, among other things. He got four years’ probation. The criminal life was exhilarating. He joined a crew that specialized in burglary. Bobby was the safecracker. He did time. When he got out he resumed the life of an outlaw. Bobby’s run in this line of work lasted seven and a half months. By then he’d had enough. He got work as a concrete finisher, more work as a carpenter. He quickly moved up to being a crew boss and ran crews that built some of the first housing tracts on Leech Lake Reservation. He moved to Alaska and worked as a roofer. He hooked iron on the tallest building in Minneapolis. Worked for U.S. Steel. “I apprenticed in Minnesota,” he explained. “But they sent me out to North Dakota to build fences around missile silos. They jerked me around and I had words with the foreman. I had a hard time working for anyone.” He got in a car crash in Alaska and came back to the reservation right when leeching was going big in the early Eighties. “At the time I was selling weed — I’d run it from the cities up north, a trunkful of it. We’d do all sorts of things — night ricing (illegal), night trapping (illegal), and that was only the half of it. And finally, well, I turned to Julie and I said to her: ‘I think I can make more money on the straight and narrow leeching than I can doing this other stuff.’ ”

Of all the things that a person can kill, collect, scavenge, trap, or snare in northern Minnesota, leeches might well be the most lucrative. More than balsam boughs (for wreaths), pinecones, furs, cranberry bark, or whatever else, leeches can be a real job. Leeches sell for anywhere from eight to twelve dollars a pound wholesale. A wholesaler divides them into dozens and packs them in styrofoam containers to be sold at bait shops and convenience stores throughout the region. In 1980, the leeching industry took in only $1.5 million, but as recreational fishing went through a boom in the Eighties and Nineties across the northern United States, the search for bait came fast on its heels, and by 2010 Minnesota anglers were spending $50 million annually on bait.

Nephelopsis obscura, the common bait leech, is found in shallow lakes, ponds, and flowages in the Great Lakes region and southern Canada as far west as the Rocky Mountains. Genetically related to the earthworm, it has a segmented body and is hermaphroditic. It is carnivorous but does not suck human blood, feeding instead on dead fish, turtles, leeches, and drowned land animals. It burrows in the mud during the day and emerges at sunset to hunt.

Leech traps are fairly basic. People use tin cans, plastic buckets with holes drilled in them, perforated plastic bags, and, most commonly, folded aluminum. Bobby baits his with beaver, beef liver, beef kidney, and other additives he doesn’t care to mention. When set in the water, the traps hang from styrofoam floats with the trapper’s name and license number tied to them.

Bobby looks at one of his books. “By April 11 of this year I had a thousand traps out. My first yield was one hundred eighty-two pounds. Not too good. By April 23 I had two thousand five hundred traps in the water. I got one hundred sixty-two pounds. What does that tell you? Tells me it’s getting shittier.”

During the leeching season he and his partner are on the water collecting traps by 5:30 a.m. They pick them up by hand, one by one, from a canoe with a small trolling motor. The traps are stowed in tubs balanced mid-thwart, and then when all two or three thousand are picked up they head back to Bobby’s shop. Once there, a crew of workers called strippers removes the leeches, sorts them, and drops them into stock tanks. Bobby pays fifteen cents a trap, which works out to around $7.50 an hour. By 11:00 everything is out of the water, the leeches are swimming in the tanks, and the baiters have begun re-baiting the traps. By early afternoon Bobby and his team are back on the water setting them. “I can set a lake in one hour. It takes me two hours to pick up all my traps. That’s three hours a lake. We work hard and we work fast. We don’t go to the landing and smoke cigarettes and talk about how much fun it was. A lot of leechers quit. They can’t figure it out. Why is this lake producing and that one isn’t? Why are these traps empty and those other ones full? The biggest thing, the most important thing, is they have to stick to it. Day in, day out. They gotta be on the water.”

Bobby won’t tell me how much he makes a year from leeching, but it is more than enough to live well on. He owns his home on the Leech Lake Reservation outright. His trucks and cars too. During leeching season, he employs sixteen people. Though it didn’t start out that way, what Bobby has now is a small business. All this runs counter to the usual mythology of subsistence: the man who turns his back on society and enters into a direct relationship with the land. In Bobby’s case, the “state of nature” is paid for by the state of man. To live off the land is still to live in relation to other people.

Bobby Matthews makes subsistence seem logical, easy somehow — something any of us could do if we just tried hard enough. But maybe not. DM, like Bobby, has worked a lot of jobs. He’s been a carpenter, a logger, a sawmill operator. He’s Ojibwe from Michigan and has lived in Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and California. He recently returned to his reservation in northern Michigan, where he opened a bait shop in his front yard. His house is small — more a cabin than a house. Fiberglass insulation covered with plastic sheeting bulges from the ceiling. When I visited, in the spring of 2012, the regulator on his gas range had gone out and the stove stood in the middle of the kitchen. He and his wife were cooking for their two children on a Coleman camp stove set up on the countertop.

DM, who asked me to refer to him only by his initials, is tall and thin, his hair — most of it anyway — pulled back in a ponytail. His hands are large and knobby and look very strong. “I’ve been all over,” he tells me. “I used to hitchhike back in the early Eighties. It was okay then. You got rides. The cops were friendly. People were friendly. I was in my early twenties then. I picked up basic carpentry skills by the time I was twenty-one. That’s what carried me through life. I could always bend a nail and hit my thumb and get paid for it.” He grew up far away from his reservation, on the outskirts of Detroit. But he didn’t like city living, and he moved north to the Upper Peninsula, where he got a job at the wood mill. “Everything up there is wood-related,” he says. “Pulp, lumber, wood fences. We were green chaining and I stacked it. We all got laid off a week before Christmas. I come back here, to the rez, and I guess I accomplished that. I’ve done something with my life. I’ve been back here seven years. If I was a flower, it’s kind of like I didn’t even begin to bloom till I came back here. I don’t want to make it sound romantic. It’s still really hard.”

DM has struggled to get hired on the rez. “Fuck it,” he says, of working for the tribe. “I did one time go down there to the tribal offices looking for a job. Everyone told me that’s what I had to do. All I know how to do is to pound nails. That was four years ago. Housing has my application. I used to go down there every six months and shake their hands and check on it. All the things I had to do — kiss ass, sell myself — and at the end of the day it was a no-go.”

There was a guy up the road who kept stopping in. He had a regular job working for the tribe, but he also dabbled in carpentry and logging. Frozen out of a tribal job, frozen out of tribal housing, and freezing in his own house, DM began to help him with his side work. They cut firewood and sold that on and off the rez. “Basically,” he says, “the outlaws rescued me. You look at all these guys — these trappers and woodsmen, these hunter-gatherers: they are all outlaws. No matter what you’re doing — whether you’re logging or cutting firewood or getting bait or whatever — you need start-up money. You need support. No one’s supporting them, no one’s giving them loans for that stuff. So all these guys gotta be outlaws. And that guy down the road, he gave me a chance and taught me stuff.”

Eventually, DM’s partner brought him into the bait business. They set minnow traps and leeched a couple of lakes and DM set up the shop near his house. They sell minnows for six dollars a scoop and leeches for five dollars a dozen. He tells me he isn’t sure how much he nets — maybe a hundred or a hundred fifty a day during a three-week stretch in the spring. The rest of fishing season is hit-or-miss. As much as moving back to his reservation was the defining moment of his life, there seem to have been many smaller moments that have wiped away that definition. Unlike Bobby he is relatively new to the woods. He is also new to the people who make the business of hunting and gathering what it is — the buyers, trappers, store owners, licensing bureaus, suppliers, and clients who together make up the subsistence market.

For all the time that someone like Bobby is in the woods, someone like DM is trying to find his way in there. And it’s grueling and depressing to be rebuffed again and again. “You know,” says DM, getting reflective again, “all those guys who hunt and trap and collect. All those guys do a lot of other things too. All of them sell weed. Nothing harder than that. Nothing more damaging than that. But they do it.”

DM’s tribe in Michigan, and mine in Minnesota, don’t seem particularly interested in supporting subsistence living, even though it could be a boon for historically depressed reservation economies. There is room for co-ops (for pinecone pickers and bait harvesters and ricers) and for expansion of markets (trucks and warehouses to transport and store the goods).

All the buyers I’ve talked to have said that the bait market will bear a lot more product, and there is also room for more pinecone and bough pickers. There is demand for all these products. There just aren’t that many people bringing them in. Which is just fine with the people who are. For most of them subsistence activity is a supplement at best. To make it full-time, as DM has learned, requires knowledge and a network of support. For DM the problem isn’t mother nature; the problem is people.

I left DM’s cabin feeling as he seemed to feel: that subsistence living was not all that different from what we think of as the regular economy. It is controlled by a few, and success is only partly determined by one’s ability. It helps to be born into it, to grow up around it, and to have the right connections. For hunter-gatherers as well as for a majority of Americans, to exist is to be a part of the service economy, to be in at the bottom, and to wish and wonder about the wants and needs of others who control the real money and live with real security.

During the fur trade the Ojibwe near the Great Lakes could make a killing because they were sitting on the greatest concentration of beavers in the world. In exchange they took payment in trade goods. Wool was light, warm, and supple. Metal pots were strong, versatile, and made food preparation much easier. A metal axe lasted for generations and saved tremendous amounts of energy compared with the manufacture and use of stone or bone axes.

Think boots, gloves, needles, thread, waterproof food storage, bullets, guns, oil, grease, kerosene, matches. Of course, people lived without these things for millennia, but they didn’t live well or long. Pre-Columbian tribal people had an average life span of not more than thirty-five years. The civilization we leave behind when we head into the woods hasn’t been left behind at all. Mankind is written into the things it makes, and when we carry matches or a gun or even a pot out into the woods, we are bringing civilization with us.

You can’t eat pinecones, but you can sell them. Same goes for leeches. Some subsistence products like wild rice and pine nuts, fruit and mushrooms, furs and meat, can be consumed as well as sold. These have a double value. But most things don’t. They only have value insofar as someone else wants them and has trouble obtaining them. So subsistence living is doubly plagued: you have to rely on nature to provide the leeches, cones, bark, fur, and so on, and you have to rely on a market determined entirely by other humans and human wants. So Bobby Matthews is just as careful with people as he is with his black books that detail all his “getting places.” “I sell my leeches to Todd Hoythya down south. I won’t go to nobody else. He’s been good to me and I’ve been good to him. He knows my leeches will come to him healthy. I’ll never short him on my count. I always get him the leeches when I say I’m going to. Same with my cones. I put an extra tray in each bushel. So he’s getting a little extra. I do the same with my leeches, I add ten percent. My buyers know what they’re getting from me. And I tell you what: it saves me time, David! I don’t have to wait around while they count out my stuff. I drop it off, they pay me, and I’m on my way, back in the bush to get more!”

Subsistence, as practiced by people like Bobby, isn’t a philosophy of quiet, inward-turning wonder about how we relate to the land. It’s a mad, violent pragmatism intent on extracting calories and advantage.

It is March, and winter is bone-deep in the north woods. It seems like forever ago that there was anything green and giving out in this world. The snow isn’t deep at all, and so the ground is frozen hard. Bobby and I are driving along an abandoned railroad grade on the south edge of Leech Lake Reservation looking for cranberry bark.

“It’s something new for me, David,” he says. “Guys have been doing it a while, and I was against it at first. I thought it destroyed the cranberry trees, but it doesn’t. They spread through their roots; they grow in clumps. If you cut it they send up new shoots. Leeching is a long way off, and I go a little crazy sitting around, and so I thought I’d try getting bark.”

Of all the things Bobby does, cutting bark is the most relaxing. You drive around until you find a stand of high cranberry bushes. “Cut ’em cock-thick, David.” We cut with long-handled pruning shears and we keep cutting until we have a few armfuls. These we load into a sled and haul back to the truck until it’s full to the top, then we head back to the house. The swamps and lowlands are frozen solid, and you can walk wherever you need to go. At the house we have coffee to warm up and then go to Bobby’s shop, turn on the radio, and peel the bark off the saplings with potato peelers. The bark is sold and used as an herbal remedy for menstrual cramps.

“Does it work?” I ask him.

“How the hell should I know?”

Even though this is a new activity, a new revenue stream, he’s gone all in. “There’s a guy around here who buys bark from the pickers. And he sells it to another outfit out of state. He doesn’t pay much; he’s keeping the price down. But what if we could do this and the pickers got a living wage?”

So in addition to cutting his own bark he buys from other pickers as well. People drop by with garbage bags full of green bark, and he weighs it and pays them in cash.

“I did some research and found out who buys this stuff, and I started dealing with him. I asked him how much he’d need to buy from me, and he told me. And I asked him what kind of quality — how much bark and how much wood — and he told me. And I gave him exactly what he needed.”

Bobby converted the back bedroom in his house for the bark processing. He has racks that run from the floor to the ceiling with large wire trays. He dumps the bark on the trays and turns on a dehumidifier and a fan and dries the bark until it is crispy. Then he crumbles it up by hand, packs it in bags, boxes these, and ships them to North Carolina.

“My guy in North Carolina will buy all sorts of stuff. Iris root. The buds from balm of Gilead. I don’t know who he sells his stuff to. Probably drug companies, places like that. We got a lot of stuff we can sell. A lot of stuff people want.” We had cut bark for a total of three hours and got just short of ten pounds. “I want people to know they can do this, David. They can do this. They can live off the land, just like I do. It beats working at Walmart or McDonald’s. What could be better than spending the day in the woods, getting exercise, and getting paid for it? It’s what we’ve done for centuries. We’ve always done this. And we can still do this. But we have to change our thinking. We have to work together, and we got to want it. I just wish our people wanted it more.”

I called Bobby in September. He had just dropped off two pickup loads of jack pinecones, $917 worth. Before I rang off he said, “Hey, check this out: I was out in the woods checking for cones and I saw the beavers and they’d been pulling up roots and cutting branches, putting fresh mud on their lodges in August. Then they stopped. They just stopped. No new feed piles. No new mud. I thought to myself, ‘Well, this is a damn strange thing! I wonder what the beavers know that we don’t?’ Maybe we’ll get some more warm weather before it gets cold, David. Maybe they know what the weather is gonna do. Think about that. Amazing, huh?” The beavers were right. And so was Bobby. The weather was warm for another six weeks, and Bobby was out there picking cones.