There were dozens of hippie acts in Haight-Ashbury in the late 1960s, but most people have only heard of a few: Jefferson Airplane, Santana, Janis Joplin, and the Grateful Dead. At the time, Jefferson Airplane was the most commercially successful, and the Dead the least. The Dead never had a Billboard number-one single, though the Library of Congress eventually declared “Truckin’ ” a national treasure. Shakedown Street went gold, but nine years after its release. They toured for thirty years, but didn’t become the top-grossing band in North America until 1991, their twenty-sixth year together. Why?

That’s the question behind Peter Richardson’s new book, No Simple Highway: A Cultural History of the Grateful Dead (St. Martin’s Press, $26.99). Jerry Garcia’s own explanation was cute — he said the band was like licorice: not everybody likes it, but people who like it really like it — but hardly enough to satisfy a historian. As you might expect from the author of books about the Bay Area radical magazine Ramparts and progressive intellectual Carey McWilliams, Richardson’s story of the Dead is a story of the Sixties and its aftermath. One strand of the Sixties, anyway, whose benchmarks include Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters; Woodstock and the Summer of Love; the Whole Earth catalog and the Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link (WELL) bulletin board, which spawned digital communities of Dead Heads as well as Wired magazine. By the time of 1995’s Tour from Hell, this version of the Sixties was a marketable commodity, and Bloomingdale’s had sold hundreds of thousands of $28.50 neckties from the J. Garcia Art in Neckwear collection.

Photograph of Jerry Garcia by Jim Marshall © Jim Marshall Photography LLC. Marshall’s new monograph, The Haight: Love, Rock, and Revolution, was published in October by Insight Editions.

Richardson writes with the enthusiasm of a recent convert, which he is. (He’s also a card-carrying member of the Grateful Dead Scholars Caucus — they’re like tapers, only they trade conference papers.) He paints the Dead as a utopian experiment in a long American tradition; they were occasionally forced to compromise, but only when one of their ideals thwarted another one. They wanted to run their own record label, but operating a business took them away from making music. They wanted to partake of an ecstatic, intimate experience with their audience, but they also relied on a huge crew — a family, really — of seventy-five; if everyone was going to eat, they were going to play stadiums. Richardson celebrates the group’s “hedonistic poverty” but also quotes Dead historian Dennis McNally as to the band’s late-Seventies needs: “Phil [Lesh] had his Lotus sports car, [Bill] Kreutzmann had his ranch, Mickey [Hart] wanted equipment for the studio, Keith [Godchaux] and Jerry wanted drugs.” They weren’t just an obscenely gifted group of musicians: they were a social institution, an egalitarian commune, and a traveling circus — a modern-day Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. They operated on a massive scale, sometimes pouring 90 percent of their revenue into a seventy-five-ton sound system that filled four semitrailers. “We’re in the transportation business,” Mickey once said. “We move minds.”

Having your mind moved is not always a pleasant experience. (Ask Mickey’s horse, which he liked to dose before riding.) People who attended the earliest Dead shows describe them as scary, even terrifying. The band had a harder blues-rock sound then, and everyone was flying. The mix of ego-disappearing drugs and time-disintegrating jams was a heady one. In later years, when the melodies mellowed, the vibe was still heavy. Robert Hunter’s lyrics were usually about suffering and sorrow and death, while John Perry Barlow’s poems, which Bob Weir sang, were abstract — creepy in a different way. Jerry didn’t like love songs, at least not ones with happy endings. He also didn’t like politics. “For me, the lame part of the Sixties was the political part, the social part,” he explained in 1989. “The real part was the spiritual part.”

The Dead, like the Hells Angels who rolled with their crew, were fundamentally outlaws. They knew that getting high, or “getting conscious,” could get you into dark corners. “We’re kinda like a signpost,” Jerry said, “and we’re also pointing to danger, to difficulty. We’re pointing to bummers.” You can get a good sense of what a bummer is in a one-minute scene toward the end of the documentary Gimme Shelter. Jerry and Phil have just landed at the Altamont Raceway to learn that Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane has been punched out by one of the Angels, who were working security for the festival. “Oh, that’s what the story is here?” Jerry says from behind his yellow sunglasses. “Oh, bummer.” Hours later, an eighteen-year-old black man named Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death by the Angels while the Rolling Stones played “Under My Thumb.” Jerry never blamed the bikers for the melee. He attributed it to “spiritual panic,” as well as the “anonymous, borderline, violent street types” in the crowd — the kind who “may take dope, but that doesn’t mean they’re Heads” — and, perhaps most suspicious of all, “the top-forty world.”

Richardson idealizes the members of the band as exemplars of integrity who rarely feuded, but times were not always easy. Three keyboardists died along the way, including Ron “Pigpen” McKernan; Mickey took a three-year hiatus after his father embezzled thousands of dollars from the group; Jerry developed a frightening heroin problem and, after his 1986 coma, had to entirely relearn how to play guitar. By that time, being a Dead Head was less about the actual music performed by the Grateful Dead and more about college students chasing a shadow of the old, weird America, and boomers remembering their good days, forever gone. Reggae, disco, New Wave, glitter rock, and punk all came and went, and still the Dead were exploring their particular stew of white roots rock, bluegrass, blues, folk, and country. When I started high school, Bill Clinton had long made it a habit to give away J. Garcia ties, and being into the band — like being into Hendrix or the Beatles — had become ossified as a life stage. In youth culture, ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, and teenagers since the Sixties have passed through the Sixties; they just tend not to remain there. What made the Dead special was that they never left. Why would they? “We’re basically Americans, and we like America,” Jerry said. “We like the thing about being able to express outrageous amounts of freedom.”

To hear Richardson tell it, the Dead were tuned-in Kilroys, on hand to midwife the births of poster art, band merchandising, the free-form album-based radio format, the — might as well say it — Internet, and, best of all, what is now a key cultural formation: the rock-concert light show. He credits an art professor named Seymour Locks, who swirled and rotated hollow slides and plastic dishes of pigment in a projector during the Dead’s set at the 1966 Trips Festival. Something was in the air, though, because around the same time, artist Bill Ham was programming kinetic murals at the Red Dog Saloon in Nevada, and Mark Boyle and Joan Hills were projecting chemical reactions in London. (Their machine also turned colors into sounds.)

It’s not hard to trace a crooked line from these experimenters back to the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens, who in 1659 combined painted glass, a lamp, and a lens to invent the magic lantern. Within a few decades, traveling European performers were slipping and rotating painted slides to make moving projections of ghosts, angels, and battles; by 1804, “phantasmagoria” shows featuring dancing skeletons toured the East Coast of the United States. In 1895, an estimated million Americans attended magic-lantern performances in opera houses, meeting halls, and churches. Many of these shows took the form of lectures on history, science, or travel; many were Bible stories and Sunday-school lessons; others incorporated live songs, stories, and animated comedy. Children played with toy lanterns at home. “It replaced the opacity of the walls with impalpable iridescences, supernatural multicolored apparitions, where legends were depicted as in a wavering, momentary stained-glass window,” the narrator of Swann’s Way remembers. “But my sadness was only increased by this since the mere change in lighting destroyed the familiarity which my bedroom had acquired for me and which, except for the torment of going to bed, had made it tolerable to me.”

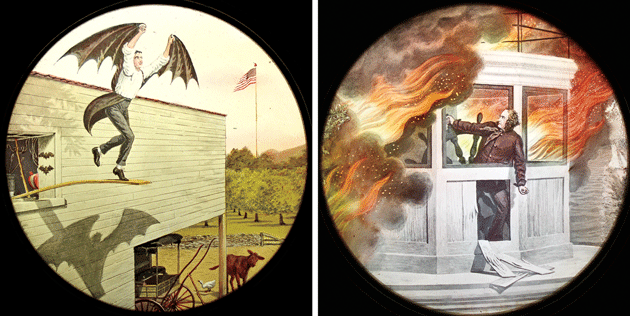

Left to right: “Darius springs into the air,” from Darius Green and His Flying Machine, and “The flames approach with giant strides,” from John Maynard. Collected in Before the Movies: American Magic-Lantern Entertainment and the Nation’s First Great Screen Artist, Joseph Boggs Beale, by Terry and Deborah Borton (John Libbey). Courtesy the Beale Collection of Terry and Deborah Borton

Proust described the magic lantern as strange, even threatening, but for many it was a quotidian amusement, and for a few, a steady job. Before the Movies: American Magic-Lantern Entertainment and the Nation’s First Great Screen Artist, Joseph Boggs Beale (John Libbey, $48) is a catalogue raisonné by Terry and Deborah Borton, independent scholars and magic-lantern professionals who have spent decades collecting, documenting, and sorting through the provenance of Joseph Boggs Beale’s slide art. Beale, the grandnephew of Betsy Ross, was born in 1841 and educated in Philadelphia, where he beat out Thomas Eakins for a job as an art teacher. He contributed to illustrated weeklies, including Harper’s Weekly (a spin-off of this magazine that ran from 1857 to 1916), and mastered architectural drawing in Chicago. In 1881, Beale returned to Philadelphia and was hired by C. W. Briggs, a wholesaler of the photographic slides, often created from etchings, that had come to dominate the magic-lantern trade. Briggs soon asked artists to execute original work, and he sold millions of these slides, although Beale is one of only a handful of artists to have signed his work or been individually credited in the catalogues. Beale also produced more original pieces than all of his colleagues combined — a total of approximately thirty-four hours, or the modern-day equivalent of seventeen feature-length films, of “screen programming.”

Briggs assigned the subject matter, most of which was patriotic or religious; there were illustrations of temperance lessons, Paul Revere’s ride, poems by Longfellow and Tennyson, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. (It’s hard to find a nineteenth-century American entertainment that didn’t involve Uncle Tom’s Cabin.) Some images were commissioned by secret societies like the Masons and the Oddfellows. For the Knights of Malta, he depicted a pitchfork-wielding devil reclining on a pile of skulls, all lit up in orange by the flames below. (He saved time by using the same images for multiple secret societies; presumably the members would have no way of knowing.) Beale had a marvelous talent for color and depth of field, and even his scenes of nature bristle with energy and movement. The Bortons are at pains to credit him with pioneering such proto-cinematic devices as eye-line matches, zooms, and dissolves, although these would have to be rediscovered by future generations of filmmakers. Those very filmmakers put magic lanterns out of business, but Briggs sold his catalogue, which made its way to stock-photo agencies, and as late as the 1970s American teachers were loading slide projectors with Beale’s images. As for the Masons, it’s said that they still use Beale’s illustrations in their PowerPoint presentations.

As the story of Beale shows, even the most popular media have limited shelf lives; they are born, they evolve, and they die. The reason why any one form or style is popular at any one moment usually involves some combination of technological possibility, organization of labor, and spark of genius. It helps if you can get more than one genius in the same place at the same time. In The B Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song (Riverhead Books, $27.95), Ben Yagoda compares the concentration of creative power in the lyricists and composers who wrote standards like “Over the Rainbow” and “I Got Rhythm” to the Italian Renaissance. And like the Renaissance, their moment ended — not in a bonfire of vanities but in an explosion of them.

Left to right: “Out she swung, far out,” from Curfew Shall Not Ring To-Night, and “ ‘Now wake, now wake, thou butcher man!’ ” from The Spectre Pig. Courtesy the Beale Collection of Terry and Deborah Borton

From the mid-1920s through 1950 or so, Tin Pin Alley flourished. “Stormy Weather,” “Let’s Fall in Love,” “But Beautiful” — the songs were written for Broadway and Hollywood and then published as sheet music, heard on the radio, and performed in nightclubs. (The name Tin Pan Alley refers to West 28th Street in Manhattan, where the music publishers clustered, and, later, the Brill Building in Midtown.) Until 1939, there was only one publishing company in town: ASCAP. It was hard to become a member, especially if you were African-American, into country, or a weirdo like the Polish accordionist Pee Wee King. But beginning in the 1930s, ASCAP raised the licensing fees it charged radio stations. Six hundred stations revolted and formed a new publishing company, BMI, in 1939, and the networks began refusing to play ASCAP songs. By the time those songs were back on the air, the way had been cleared for new songwriters, and a new sound: rock and roll. In 1939, there were 1,000 composers and 137 publishers collecting licensing fees; by 1964, the songwriters numbered 18,000, and the publishers 10,000.

This was a battle of business as well as taste, with Nat King Cole proclaiming in song that, Elvis Presley notwithstanding, “Mr. Cole won’t rock and roll.” An eighteen-year lawsuit launched by an ASCAP writer failed to prove that the networks favored BMI songs, but it did uncover payola. “What they call payola in the disk-jockey business, they call lobbying in Washington,” cracked Alan Freed, the DJ usually credited with introducing R&B to white audiences, whose career was destroyed by the scandals. ASCAP even took its case to Congress, hoping to prove that the airwaves were monopolistic and, worse, ruining music. “Yakety Yak” and its ilk did not cause the consternation among our lawmakers that one might have expected. “My daughter bought it,” said one. “What are you going to do about it?”

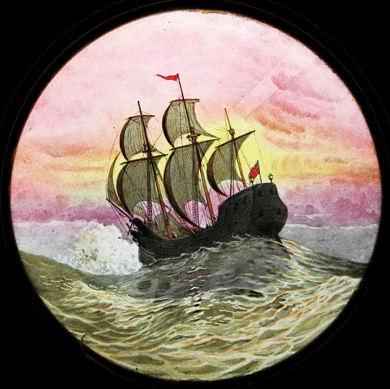

“The Mayflower,” from Patriotic Order of America. Courtesy the Beale Collection of Terry and Deborah Borton

What’s a “standard,” anyway? The journal American Speech defined it in 1937: “Standard, a number whose popularity has withstood the test of time.” Yagoda opens The B Side with a story about jazz pianist Keith Jarrett’s attempt to write a standard of his own, a song that would sound like something that “existed before.” It seems a perverse and even foolish exercise, like buying a pair of pre-ripped jeans; how could you make something sound timeless if it hasn’t existed for any time at all? Sometimes it happens that way, though. A coal miner once asked the Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter what he thought the original writer of “Cumberland Blues,” a track from Workingman’s Dead, would have said about the band’s cover of this obviously authentic Appalachian folk tune. Surely Hunter, who had himself written the words to “Cumberland Blues,” could have received no higher praise.