First, she tries counting. The numbers move sluggishly through her head in single file, like people in a line at the post office or at the bank or at the discount supermarket where you can only pay with cash so the line is always long and she is always frustrated by the time she reaches the counter, and so, to compensate, she always tries to be extra- friendly to the cashier, to be sure to instruct him or her to have a nice day after she gets her change back, because it seems worse, somehow, to be a cashier in a discount supermarket than it would be to do the same job at a place that sold expensive gourmet foods, although when she thinks about this now, so late at night that she doesn’t even want to look at the clock to find out the time, she thinks, Why would it make a difference whether you ran a cash register at a place where people buy brie and figs and Ethiopian fair-trade coffee, instead of at a place where people buy Pampers and Wonder Bread? In reality, she thinks, working at a gourmet market is probably worse because of the annoying people who shop there, the men and women in stylish business-casual clothing, or athletic wear because they are coming from or going to the gym, all of them buying organic heirloom tomatoes and the latest variety of ancient grain that is supposed to make you live forever and all of them exuding an air of self-satisfaction, of superiority, of knowledge that they are worthy and admirable and enlightened beyond ordinary mortals and wanting to chat with the cashier about his or her day and about the food they’re buying and the fabulous, complicated meal that they’re going to make with these ingredients, which is really just another way of showing off when you get right down to it. Do you really want to see those people every day? On the other hand, at the discount supermarket you might see people buying weird, sad, lonely food, like the man who’d been in front of her in line the other week who was severely overweight and buying twenty frozen dinners and nothing else, or the unnaturally skinny woman buying a big crate of caffeine-free diet soda and nothing else, or the mother with three children trying to figure out what she could afford with her WIC voucher, carefully watching the total as it came up on the screen, putting aside the things in her cart that she could not afford that week. For a cashier, that had to be depressing. Add to that the threat that you would be replaced any day now with one of those automatic swiper machines that don’t actually work and always require assistance before the customer can check out, and you have a pretty unhappy work environment as a cashier one way or another.

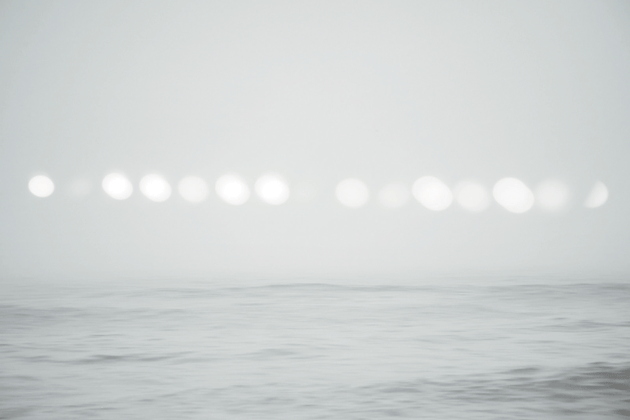

“White Dots,” by Mary Ellen Bartley, from her series Sea Change. Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York City

Or maybe she is just being a snob and actually being a cashier can be a fine job and it’s only because of her particular privileged background that she assumes it would be miserable rather than fulfilling to be a cashier, because how would she know? The closest she ever came was waiting tables at a restaurant and that job was not terrible, she still has some good memories of the characters that she met among the customers, the man who came up to the counter and asked her if she could recite any Shakespeare and she spoke aloud the prologue to Henry V because she knew it by heart, or the time she . . . well, actually that is her only good memory of that job, the rest of it was boring or unpleasant and involved mopping floors and stacking dishes and wiping down tables and anyway she knew that she was going to leave and go away to college and that this wouldn’t be her job for the rest of her life, she would be able to go on to something better or something that at the time she thought would be better. She did go to college, and she majored in French, and she lived in Paris for a few years after she finished her degree and now she works translating technical manuals and she used to be married to a man who appeared to be steady and reliable if a little dull, qualities that she told herself were a good antidote to her own tendency to fret too much about small and insignificant things, and who had a successful career in hospital administration, but who suddenly, about six months ago, came to the conclusion that he’d had enough of expending his energy and intelligence working in a health-care system organized for the benefit of for-profit insurance companies, and decided to move to France. She found this moderately ironic since, when she had been yearning a few years previously to ditch everything and go back to Paris, he had insisted that they could not do this because he’d put too much time and effort into developing his career in the United States and he did not want to throw away what he’d worked so hard to build. She pointed this irony out to him during the brief period after he’d announced that he was moving out but before he had actually departed for good, and although he readily agreed with her that, yes, there was some irony in his choice, he did not change his mind. He said that she worried too much and that he didn’t want to deal with it anymore. And she said: This won’t make me worry less. And he said: I know, but it will no longer be my problem.

For the first few months he was gone, she had seemed to be coping admirably, in fact she seemed to be adjusting to their separation astonishingly well, even to be calmer than she had been before he left. She told herself and her friends and her mother that perhaps it was for the best, they had never been perfectly matched after all, she had always longed for someone more expressive and exciting, who shared her love of literature and art, who longed to travel, who had a greater capacity for amazement. Perhaps this could be a new beginning and a chance to find a truly fulfilling life. She sold the house they had lived in together, rented an apartment within walking distance of a good coffee shop and a discount supermarket. She saw friends. She saw movies. She started taking a swing-dance class.

But then, two days ago, as she was drifting off to sleep, her phone rang. Her mind surfaced from the soft, dark pool in which it had submerged, just in time to hear the last cycle of tones die away before her voicemail picked up. Her phone was in the kitchen and at first she thought that maybe she could burrow back down and find her way to the threshold of sleep again, but no, she was awake, wondering who had called so late. Her brain began to spin and gather speed. Could it be an emergency, something seriously wrong? A friend in trouble? Her mother in the hospital? She climbed out of bed and made her way down the hall and took the phone from the counter where she’d left it and stared at the string of digits on the screen. It was not a number that she recognized, but the country code was 33, and the numbers that followed were the area code for the region where, as far as she knew, her husband now resided. She knew no one else who might be calling her from there. Right now in Europe it was early morning, well before dawn. She looked at the screen, but there was no icon telling her that anyone had left a message. She listened to her voicemail anyway, just in case. Nothing. She considered calling the number back, but she thought, suddenly, angrily, that she did not want to give him the satisfaction of having her jump to attention just because he dialed her number. Suppose he had not meant to call her at all; he’d only misdialed and that was why he hadn’t left a message? Or what if he had meant to call her but then changed his mind? When he answered the phone his voice would be dry and distant and polite in that way he could be when he wanted to protect himself. She could not bear the idea of having him treat her coolly, so instead of calling him and asking him what he wanted, she put the phone back on the counter and left it there and went and climbed into bed. She lay down and clicked off the light on her nightstand. She closed her eyes and tried to go to sleep again, but she could not, and all that night, and the one after, and now again tonight, she has lain awake, staring into the dark, her mind like something stranded on a beach, longing to swim out and get lost at sea but unable to reach the water’s edge.

Now when she looks over toward the window, there is a blue glow seeping in beneath the blind. She does not know if she is angrier with her husband for calling her and unsettling her so much or with herself for allowing something as trivial as a phone call to make her come unhinged. She sighs. She looks over at the numbers on the alarm clock on the nightstand. Soon it will be time for her to get up. She might as well go and make some coffee and get ready to start her day.

Since counting didn’t work, the next night she tries imagining the sound of ocean waves. This is what it said to do on a website she found called Overcoming Insomnia, which she read when she should have been working on her current project, a book instructing engineers on the maintenance and repair of machines that shape the steel exteriors of cars and trucks on the assembly lines of European subsidiaries of American car manufacturers. But she was too tired to concentrate and had drifted online looking for answers to the question of what to do if you cannot go to sleep.

Imagining the sound of the sea seemed like a good exercise when she read about it, even though she is extremely suspicious of the whole idea that you can “overcome” insomnia, which sounds to her too much like “overpowering,” as if you were supposed to triumph by an act of will, to wrestle your sleeplessness into submission, and which evokes intense concentration or brute force or both, when really what she needs seems like the exact opposite of those: a kind of soft dissolving of herself during which she turns from a person into a cloud of gold dust that hovers, shimmering for a minute before dispersing into the dark with a sound like somebody blowing out a candle. Insomnia seems more like something you have to sneak underneath or find a hole in the fence of or find a way to flow around than something that you can overcome. Also, the man who produced the website, Howard Francus, M.D., whose smiling photograph appears on many of its pages, has written a book with the same title, Overcoming Insomnia, and really the site is a promotional platform for his book. She can’t help suspecting that the information Dr. Francus put on the website for free is only the peripheral stuff, the least effective and therefore least valuable insights and techniques he has to offer, because wouldn’t he want to keep the really good stuff, the real secrets, the magic, surefire answers, to himself so that you had to buy his book? What would be the point of using the website to promote his book if everyone just read the website and was immediately cured and no one needed to pay $24.99 plus shipping and handling to find out how to go to sleep at night?

Nevertheless, in spite of her profound misgivings, while lying in the dark she tries to imagine the sound of the ocean. It has been a long time since she went to the ocean. As a child she used to live near the coast. Now she lives in a city that, although it is on a lake, is very far from the ocean. There are hundreds of miles of dry land in every direction. She and her husband had been planning before he left to go to the beach as soon as both of them could find time for a vacation. She loves the sea, in fact, the smell and the sounds of it, the way it throws the light back up into the air so that all the objects near the shore, the houses and the people and the trees and the grass bowed over on the dunes, are tossed around inside a storm of light. How she misses the sea! And she and her husband never did get around to going there together because it always seemed like there was some reason to postpone the trip, either they needed to go and see his family or hers, or there was some reason why he couldn’t leave work, or she had taken on too many projects to go away from home for an extended time, and so they delayed and delayed and sometimes when they were in bed at night and felt close to each other either because they had made love or just because some of the cold distance between them seemed to give way a little, they would talk again about going to the ocean, they would promise to make the time, they would get down the calendar and mark off a week and determine that the next day they would each do what was necessary to ensure that they could go away. But then something would come up and it wouldn’t happen and after a while they stopped talking about it and then they stopped talking about anything at all.

At some point she realizes that she has said to herself that “they” felt close to each other and that “they would determine” to finally take the time to spend together, but in fact she doesn’t know whether it was only she who felt these things, the closeness and the renewed goodwill toward their marriage. She supposes that her husband shared these same emotions, but it is just as likely, given what happened later, that he was feeling and thinking something entirely different, although what it was she cannot know. He is a sealed box to her now, his mind and heart entirely opaque, and what is worse she understands that he was always this way: it only seemed that she could see inside him, all the way to the bottom of him, as it is possible to see through shallow water at the edge of the sea.

Is she still concentrating on hearing the sound of the ocean, as Dr. Francus suggested? When she tries to call it back, all she can get her mind to produce is the grating sound of different kinds of engines, the hyperactive shrieking of a leaf blower or the nasal buzz of a lawn mower or the slicing, snorting sound of a motorcycle. Now the motorcycles multiply, there are many motorcycles all driving slowly through her head together. They rev their engines. There must be ten or twelve of them at least. She turns on the bedside light and fumbles on the floor for her glasses. The light coming out of the lamp is like a bouquet of knives. Is that too overwrought? How else to describe how piercing it is? It is made of levitating shards of glass. Tomorrow, if she still can’t get to sleep, she will make an appointment to see her doctor and get some sleeping pills. But she doesn’t want to do this quite yet. Because what if the phone rings again, late at night, and she is too sound asleep and she misses it? Maybe she will give it just one more night before she gets the medication. Or maybe two.

The following night, she cannot get the idea out of her mind that someone is going to come into the apartment. She cannot picture the person’s features, only his unusual height and bulk, which is masculine in a general way without taking on the concrete features of an individual man. He is not white or black, but he does appear to be wearing her father’s favorite old cardigan, which was gray with round leather buttons and leather patches on the elbows. This is his only distinguishing characteristic. She doesn’t know how he is going to get into her apartment. She has already checked that both doors and all the windows are locked. And yet every time there is a noise close by, either from the street or somewhere inside the building, she starts, convinced absolutely that it is the footsteps of this man. She can hear him coming down the hall, approaching the door of her room. He is right outside. He waits in the hall outside her door until she has almost forgotten he is there, and then he makes a noise.

She tells herself that there is no man, but the more she tries to convince herself of this, the more he takes on clear detail. His eyes are green and one is slightly higher than the other. His nose is flat and broad at the bottom, so he looks like a figure in a painting by Picasso. He does not appear to have a mouth at all, as though whoever made him forgot to give him one, but rather than being horrifying as you might imagine a person with no mouth to be, this gives him a quizzical kind of expression like he is listening to her with genuine curiosity, his head tilted slightly to one side.

What would she do, she wonders, if there really were a man outside her door? Her bedroom door has a lock on it, but she does not usually lock it at night because there is no one else in the apartment and because she worries about what would happen if there was a fire in the middle of the night, whether if she locked her door it might not make it more difficult for her to escape or for the firemen to come in and rescue her. She has to balance the concern that someone might get into her bedroom with the concern that she might not be able to get out in an emergency. She imagines the fire chief shaking his head sadly as the local news reporters hold microphones out to him in front of the burned-out husk of her apartment building, and talking about how they managed to get everyone out except for one woman up on the seventh floor who had locked her bedroom door, so they couldn’t reach her in time. Asphyxiation, the fire chief says. People don’t think about these things. Why would she lock her door like that? Was she worried about someone coming into her apartment? That is just ridiculous.

But is it so ridiculous? These things do happen, men breaking into women’s homes and stealing things or assaulting them or worse. If she heard someone outside her door, what would she do? She could call 9-1-1 and hope they arrived fast enough to rescue her. She could try running out of her room really suddenly, hoping to surprise the man so much that she had a chance to get away, run down into the street, sound the alarm. She could try talking to the man, to find out what he wants, to appeal to his human side not to hurt her.

Outside her door, there is a sudden loud creak, like the noise made by a stomping foot. He is right there. She sits up in the bed and turns on the light. The part of her that believes there really is someone in the apartment screams at her not to do this, that she has just given away her presence and now, surely, he will come in and — what? Kill her, most likely. She tries to reason with herself. There is no one there. She needs to go out of her room and make certain of this. Maybe then she will be able to come back to bed and get some sleep.

She goes to the door. She takes a deep breath. She opens it, quickly, and sees that the hall is empty. But of course he could have withdrawn into another room, he could be hidden right now somewhere out of sight but still watching her. She walks around the house turning on the lights in each room, opening the closet doors. Soon the whole apartment is bright from end to end. She sits down at the kitchen table and remembers that when she would get scared like this in the past, which didn’t happen very often, her husband would do what she has done now: walk through the house, turn on the lights, prove that there was no one hiding, no ghosts, no people, no one there but the two of them. Sometimes he would do it impatiently: Stop being so silly. But sometimes he would do it gently, quietly, showing her the rooms with nothing in them to be frightened of. When he did this, she would calm down immediately. She would sleep happily and without interruption for the rest of the night. She would be aware of his body stretched beside hers in their bed, appreciative of its presence, because who else would have cared for her in this small, absurd way, even some of the time, except for him?

Now she sits down at the table in her dining room, with all the lights blazing around her feeling extra bright, as they do late at night. She puts her elbows on the table and her head in her hands. No one comes either to comfort her or to harm her. She is all alone.

She tries, in this order: valerian-root tea, which makes her lose feeling in her tongue so then she is lying in bed awake with a numb tongue in her mouth that feels like something someone else left there promising to come back and get at the end of the day but then forgot; melatonin, which makes her more wide-awake through the night, so that even the fitful sleep she has been managing to get evaporates; a strange kind of herbal tea that she buys from a hippie herbalist store near her home, which smells like armpit and looks a bit like armpit hair but cannot, she tells herself, possibly be in any way really related to armpits. None of these things work. She keeps her phone by her bed, but it does not ring.

Then, one night, about a week later, she is lying in bed thinking about global warming. This is a topic that she has been returning to at night quite often, thinking about how the difficulty with trying to solve global warming is that anything you do, any effort human beings make, whether it is holding a conference or publishing a book or making a movie to try to spread the word and convince people that the problem is real, only adds to the problem. Almost everyone, in America at least, who goes to see the movie will have to drive a car to get there, or if they watch it at home, they’ll watch it on a TV that was made in China in a factory that uses fossil fuels and then was sent to the United States on a freighter that also uses fossil fuels, and while they are watching the film, they will be using electricity that also probably comes from fossil fuels. Similarly, if they hold a conference, all the people who travel there will have to fly and stay in hotels and take taxis. Basically, the only thing that you can do that will have a positive effect on climate change, unless you are a scientist who is working to invent some brilliant alternative to gasoline and coal, is nothing. If you do nothing, travel nowhere, eat nothing, use no light, and don’t drive, you will not be contributing to the problem. Otherwise, you will be. Is anything I do, she thinks, actually worth the damage that I cause just by being alive in this time and place? Really, the only time when we aren’t damaging things is when we are asleep, in the dark in our beds, and now she doesn’t even appear to be able to do that. Maybe it would be better not to exist, better to disappear.

What if no one was able to sleep anymore? What if we have created a world of such uncertainty and such loneliness that one by one everyone in America found that they were unable to fall asleep? Each one of us is awake in our separate apartments that we don’t share with anyone else because we didn’t want to stay with our parents and we couldn’t get along with our spouses and fewer of us than ever have children and even then our children don’t stay with us for very long. Each one of us is wandering around our lit-up rooms, our minds scurrying down corridors like mice in a maze, unable to find our way to the soft places where we feel blessed and able to stop striving and to allow ourselves to float along for a while on the currents of the world, which is so much bigger and more mysterious than we can imagine. Maybe we are lonely for a world that we do not and cannot understand, which swirls around us in a beautiful storm and for which we cannot be held responsible.

She realizes that she is falling asleep. She feels her body softening, her bed starting to sway gently like a boat on a lake. Her room is filling up, flooding, with a substance that looks like dark ink but that she knows will not drown her. It is up to the edge of her bed. Then it spills over, traveling down the channels in her sheets and bedspread, buoying her up so she starts to float away.

And then the phone rings. It slices through the softness of her dream with its hard, bright, electronic sound. She is not surprised to hear it, however; she has the sensation that she had been expecting it would ring just then, just at that moment. She gets out of bed and she feels light and certain. The leaden haze of the last week, brought on by sleeplessness, has gone and her head is clear and her movements are sure and graceful. Even though she is just walking down the hall in her apartment she can feel the swish of her nightdress against her legs in a way that is pleasant and sensuous, her bare feet on the cool floor. She reaches the kitchen as the phone is on its third and final ring and she plucks it off the counter and she answers it.

On the other end of the line, she can tell without his even speaking, is her husband. He says: “Don’t worry. You don’t need to disappear. Everything you do is valuable for its own sake. I love you and this love illuminates all that you do and everything about you. Even if I’m not there now, this is still true.”

“How did you know that I was thinking about disappearing?” she asks.

“Because you are dreaming,” he says. “Because this is a dream.”

“Then I’m asleep?”

“That’s right.”

Of course this is a dream, she thinks. He is not really calling her. In real life he never used words or phrases about love and illumination. Strangely, though, she is not disappointed. She can feel the truth of what he has said, whether he really said it or not. She wants to hear him speak again, so she asks: “Will you always love me?” “Yes,” he says, “in a way I will. I will think of you every day of my life and often I will wish that I had not left. But that does not mean that I’ll come back.”

Again this seems right to her. She happens to glance down at her feet, and it occurs to her that, since she is dreaming, she would like to float a little way above the floor, and so she does, feeling herself lift off the ground, her body growing weightless in the middle of the air. She is still holding the phone against her face, but she is no longer paying attention to her husband or what he might say next. She drifts toward the window of her living room, which is open, although she knows that is not how she left it when she went to bed. Outside, there is the nighttime street, with its pools of light, the complicated maps the trees make against the sky. Her husband asks: “Do you miss me?” and she remembers that he is there, on the other end of the line. His voice sounds like an insect. If she reaches out, she could pull herself over the sill and swim out into the night. “I have to go,” she says. She puts the phone in the pocket of her nightgown. And then she is away.