In the nineteenth century, while the European novel was becoming the preeminent narrative form for grown-ups working through the grown-up problems of marriage, adultery, and career, Americans were writing adventure stories for boys. The classic plot featured a white man — or boy, or man-boy — on the run from the “sivilizing” effects of mothers and wives and responsibility, headed straight for the hearts of dark forests and the open arms of a dark-skinned man. Natty Bumppo had his Chingachgook; Ishmael, his Queequeg; and Huck, an older, wiser, tenderer slave named Jim. It’s almost impossible to overstate the importance of Huckleberry Finn. The great grinding gears of American literary history more or less depend on the myth that Huck and Jim are genuine buddies, and that their friendship is a symbol of golden childhood, homoerotic bonding, the love of the black man for the white, and the utopian pleasures of a floating world free of women. “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey!” was the title of Leslie Fiedler’s unforgettable 1948 essay on our “national myth of masculine love,” which today survives, in whitewashed form, under the moniker “bromance.”

In “Rivers,” from his new collection COUNTERNARRATIVES: STORIES AND NOVELLAS (New Directions, $24.95), John Keene takes aim at this sacred cow and shoots it straight in the face. The story tracks Jim’s life after the journey down the Mississippi — his domestic arrangement involves not one but two women, an excess of “sivilization” that proves its undoing — and culminates with the former raft mates fighting on opposite sides of the Civil War. Maybe the idea sounds a little corny in summary, but the execution is sure. “Rivers” ends with Jim lying hidden between Montezuma cypresses and raising his sights to an open eye. Huck had

his gun aimed at me now, other faces behind his now, all of them assuming the contours, the lean, determined hardness of his face, that face, there were a hundred of that face, those faces, burnt, determined, hard and thinking only of their own disappearing universe, not ours, which was when the cry broke across the rippling grass, and the guns, the guns, went off.

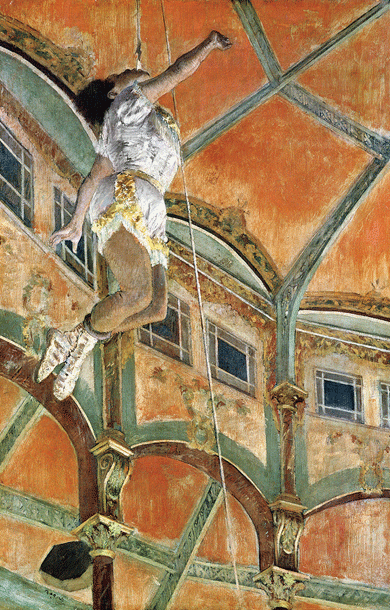

Counternarratives is an extraordinary work of literature. Keene is a dense, intricate, and magnificent writer. He was an early member of the Dark Room Collective, which in the Eighties and Nineties incubated a significant group of African-American poets whose ranks included Thomas Sayers Ellis, Sharan Strange, Kevin Young, and Natasha Trethewey, and he has translated Brazilian writers as well as texts from French and Spanish. Keene’s first book, Annotations (1995), was an experimental autobiography about growing up in St. Louis. In 2006 he collaborated with the artist Charles Stackhouse on Seismosis, an illustrated book of poems. Counternarratives is his first prose book in twenty years. An encounter narrative is usually a letter or diary entry written by a colonizer about his so-called discovery of native peoples, but Keene’s narratives meld fact and fiction, speculating about events that happened, or didn’t happen but could have, or didn’t happen but should have. Some of them are narrated as interior monologues of historical persons: the African-American composer Bob Cole, who cowrote the musical A Trip to Coontown and drowned himself in a stream in the Catskills; the Mexican poet Xavier Villaurrutia; Miss La La, a circus performer of the 1870s known for being hoisted seventy feet in the air by a rope she held between her teeth, who was also the subject of a painting by Edgar Degas. “I aim to exceed every limit placed on me unless I place it there,” La La says of her constrained acrobatics, “because that is what I think of when I think of freedom.”

It’s a line that could apply to many of Keene’s characters, but La La is the only one who states it so baldly. Most of the stories in Counternarratives evade such clarity of theme, and many of them forgo conclusions, leaving off with em dashes or ellipses, suspended in a moment of indeterminacy. In “The Aeronauts,” for example, a Philadelphia freedman with an uncanny memory joins the Union Army Balloon Corps. The story ends with him in the balloon, feeling “something not quite fear and not quite elation, I can’t put a name to it, I try to utter it but cannot.” Naming it, Keene suggests, would only contain the moment, and make it less than what it is. His characters refuse to accept freedom that is given by others — they either take it by force or resist it altogether. In this way they are also the avengers of Twain’s Jim, who wasn’t aware of his freedom until he had gone to great trouble to gain it a second time.

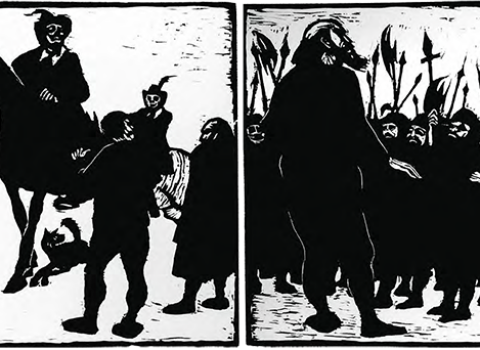

The first and best section of Counternarratives contains psychosexually intense stories about colonization, slave rebellion, witchcraft, sorcery, and Catholicism. “A Letter on the Trials of the Counterreformation in New Lisbon” begins when a priest named Dom Joaquim D’Azevedo is sent to take over a monastery in Alagoas, Brazil. What D’Azevedo finds is not unlike what the sea captain Amasa Delano discovers in Melville’s Benito Cereno: an invisible order of black slaves controlling, through violence, the visible hierarchies and rituals of daily life. In “Gloss on a History of Roman Catholics in the Early American Republic, 1790–1825; or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows,” a young Haitian slave named Carmel suffers fits of possession during which she draws scenes of mayhem that come to life. What Carmel wants is more complicated than revenge or freedom: she wants to escape, to follow her mother, a voodoo priestess who is long dead and residing in the next world.

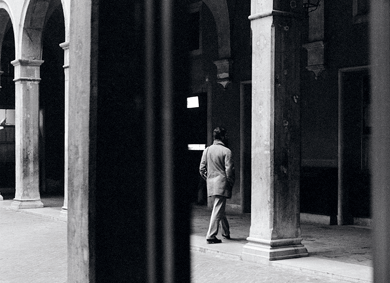

Not all encounter narratives take place at the barrel of a gun; some require only a telephoto lens. In the winter of 1979–80, the French artist Sophie Calle began tracking strangers through the streets of Paris — “for the pleasure of following them, not because they particularly interested me.” She took their photographs. One night, at an art opening, she was introduced to Henri B., a man whom, coincidentally, she had followed earlier that day. When he mentioned that he was leaving soon for Venice, Calle decided that she would go, too. She packed a set of disguises, including a blond wig, a veil, and a scarf, along with a mirrored camera attachment called a Squintar, which allowed her to point the camera away from the subject she was photographing. She departed on a night train that left the Gare de Lyon from Platform H.

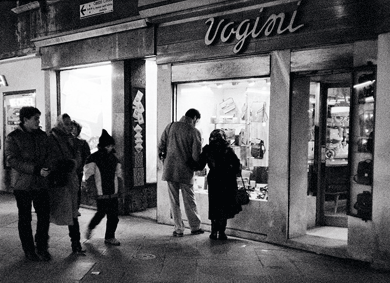

Serendipity gets Calle started, but stamina makes art. She rings up 125 hotels until a voice at the Casa de Stefani, a hundred meters from her pensione, tells her that M. Henri B. is out for the day. Part private detective, part femme fatale, part psychopath, Calle spends days stalking her subject and his wife up the calli and through the campi of the city; when they board a vaporetto, she boards the vaporetto; when he crouches down to take a photograph, so does she, several seconds behind. She grows reckless, and one day, when Henri is alone, she follows too close. “Your eyes,” he says to her. “I recognize your eyes; that’s what you should have hidden.” Henri takes a picture of her. But when they part and she lifts her camera to capture him dead-on, he blocks his face with his hand. “That’s against the rules,” he decides, cheerfully claiming the power due his position — no longer the hunted, but an able co-conspirator.

Three years later, in 1983, Calle published the record of her twelve days in Venice. SUITE VéNITIENNE (Siglio Press, $34.95), which is being reissued this month, is a handsome deep-blue hardcover, quite slim, in which brief, diaristic entries are interspersed with grainy black-and-white photographs and orange-and-pink maps. Calle, who had already arranged for a private detective to follow her for another project, The Detective, would go on to make other artworks about strangers. For The Address Book, she met the people listed in a stranger’s address book; for The Hotel, she took a job as a maid and documented the rooms she cleaned. To make Take Care of Yourself, she asked 107 women to analyze the last email Calle’s lover had sent. Calle’s work is a record of intimate events from her life, but the meaning of those events is stylized — aestheticized and detached.

Suite Vénitienne is a simple and haunting document, a record of madness and opportunism and unmotivated obsession. Henri B. could be any man. He is any man. Calle did not follow him to know him, or because she loved him. She acted like a lover in order to manufacture pure desire: desire not of an object but of desiring itself, which she pursued from dream into life.

Reality wasn’t directly relevant,” one character thinks, all too relevantly, in Nell Zink’s manic new novel MISLAID (Ecco, $26.99). The fun begins in the hazy 1960s at the all-female Stillwater College, a former plantation decked out with Virginia creeper: “A mecca for lesbians, with girls in shorts standing in the reeds to smoke, popping little black leeches with their fingers, risking expulsion for cigarettes and going in the lake.” One of these lesbians is a would-be playwright named Peggy, and before you can say “freshman orientation,” she’s shacked up with the resident campus queen, a gay male poet and professor named Lee Fleming who lives down the lake and paddles to class in a canoe. Their eventual marriage isn’t exactly a sham — “vestiges of heterosexuality . . . cosseted like rare orchids” produce two children — but neither does it provide what you might term fulfillment. Peggy drowns Lee’s car and runs off with their daughter, Mickey, leaving Byrdie, the boy, behind. Comic disguises ensue. Where some require wigs and scarves, however, Peggy makes do with paperwork and chutzpah. After she steals the identity of a dead black child for her daughter, she and Mickey pass as Meg and Karen Brown. No one questions it. “To be perfect (adorably wee and blond) yet marked for failure (black and dressed in rags) — don’t we all know that feeling?”

The Browns follow the local migratory pattern, first squatting in Virginia swampland and then moving to a housing project. Karen’s best friend is the school’s only other black kid, a bespectacled boy named Temple who loves James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, and My Dinner with Andre. Eventually Karen and Temple head off to the university in Charlottesville, where Byrdie also happens to be enrolled. The result is pretty much the miraculous reconciliation that you’d expect, with the additional complication of a sheet of acid and a fraternity drug bust. The inevitability of the finale isn’t unsatisfying, but it’s too bad that the last chapters of Mislaid devolve into a patter of dialogue, because Zink’s energy pulses in narration. Her voice is the main attraction.

Zink is original, unsentimental, erudite, and something of a naturalist. Her vocabulary is tremendous. In Mislaid, as in The Wallcreeper, her other published novel, her characters drop knowledge of twentieth-century novels and Romantic poetry, and can reliably identify specimens of flora and fauna. Her narrators always speak French. Her sentences are penetrating and agile. “Like many fresh human beings new to the world, Karen assumed people’s thoughts resembled the things they said.” “Meg felt more strongly than usual that many thoughts life had taught her to articulate were not her own, while many of her thoughts went unexpressed for lack of a suitable audience.” “The dean recalled the one Black Student Alliance party he had attended as a bleak affair. It was hard to say what had depressed him more: the studied footwork of the couples on the dance floor, or the heartrending petty bourgeois piteousness of cucumber sandwiches passed around by accounting majors whose overly colorful bow ties had been expressly chosen to keep them from looking like waiters.”

Too much? It’s certainly the kind of sentence that a more cautious white writer wouldn’t risk. Zink — who grew up in Virginia but has lived in Germany since 2000 — unpiously revels in her grotesque New South fantasia, where gays and lesbians fall in love with each other and white people pass as black and black people don’t notice racism until someone gives them a copy of Coming of Age in Mississippi. It’s hard to say whether the reverse-passing plot is a prank to push buttons or a satire of white privilege — maybe neither. Whatever it is, the stunt has the weight of fictional truth. The social meaning of race trumps the fact of skin color with the ruthless inevitability of cliché. When Peggy is a white lesbian, she’s a housewife trapped in a decaying gothic compound; after adopting a black identity, she becomes a single mother dealing drugs to get by. But to say that reality is not relevant isn’t the same as saying that things are unreal. A blue-eyed, blond black girl would have been an exaggeration, not an alien, in midcentury Virginia, where the one-drop rule determined legal identity.

Passing, of course, is a subject as familiar to American literature as the fabled journey down the Mississippi. In Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson, a slave named Roxy switches her son Chambers, who is one thirty-second black, with a white baby named Tom. Only fingerprints can restore each to his rightful place, but what is that? Put back in their proper places, the white boy raised black is an illiterate, ill-mannered misfit, outcast and nowhere at home; the black boy raised white is a murderer but valuable property — too valuable to be sent to jail. Instead, he’s sold down the river. Karen Brown’s restoration as Mickey Fleming is less traumatic, but that’s just another way of saying that Mislaid isn’t realism or counternarrative or even comedy. A hidden child, a magical reunion, the triumph of innocence — it is, in a word, romance.