Peter Rasmussen was always able to identify with his patients, particularly in their final moments. But he saw himself especially in a small, businesslike woman with leukemia who came to him in the spring of 2007, not long before he retired. Alice was in her late fifties and lived in a sparsely furnished farmhouse outside Salem, Oregon, where Rasmussen practiced medical oncology. Like him, she was stubborn and practical and independent. She was not the sort of patient who denied what was happening to her or who scrambled after any possibility of a cure, no matter what the cost. As Rasmussen saw it, “She had long ago thought about what was important and valuable to her, and she applied that to the fact that she now had acute leukemia.”

From the start, Alice refused chemotherapy, a treatment that would have meant several long hospitalizations with certain suffering, a good chance of death, and a small likelihood of truly helping. As the illness progressed, she also refused hospice care, though she did accept palliative blood transfusions. She kept meticulous track of her symptoms and hemoglobin levels; when she was too sick to come into Rasmussen’s office, she sent her husband with long, detailed letters full of updates and questions. She wanted to live until January 1, for tax purposes. Then she wanted to die at home.

Six months after Rasmussen started seeing Alice, he wrote in her chart about his admiration for her and her husband: “Together they are doing a wonderful job not only preparing for her continued worsening and imminent death but also in living a pretty good life in the meantime.” But there were more fevers and abscesses; there was more bleeding and weakness. Alice sent Rasmussen a card with a watercolor of flowers on the cover. “I don’t think I’m going to last much longer,” she wrote, “so I wanted to thank you now for letting me order my medical care à la carte.” In late January, she asked him to write her a prescription for pentobarbital.

Three days later he arrived at the farmhouse with four vials of bitter liquid — a handier form than he’d dispensed in earlier years, when he’d had to break open ninety capsules of secobarbital into applesauce or pudding. Though the law didn’t require it, he liked to bring the drug from the pharmacy himself, right before it was to be used, so that there would be no mistakes. It was one of the personal rules he imposed on the process to help himself feel less terrified.

Rasmussen made himself scarce during Alice’s goodbye with her husband, which was long and affectionate. There was no rush, he told her, as he always told his patients; he’d be glad to come back anytime. But Alice was sure. Rasmussen was impressed. “There was no prolonged final statement,” he remembered. “She just drank it down.” She fell asleep, and after a few minutes he interrupted her husband’s reminiscing to let him know that Alice had stopped breathing.

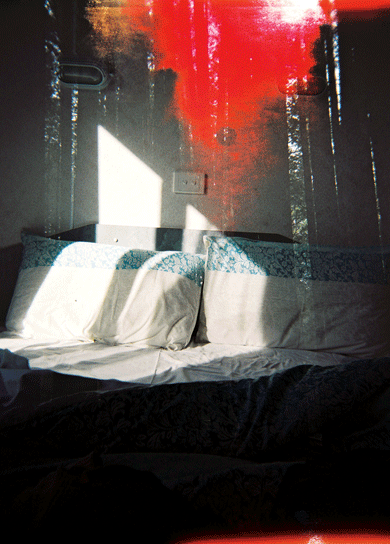

Over nearly three decades as a physician in Oregon, the first state to allow physicians to prescribe drugs for the purpose of ending patients’ lives, Rasmussen developed many strong beliefs about death. The strongest was that patients should have the right to make their own decisions about how to face it. He remembers the scene in Alice’s bedroom as “inspiring, in a sense” — the kind of personal choice that he’d envisioned during the long, lonely years when he’d fought, against the disapproval of nearly everyone he knew and all the way to the Supreme Court, for the right of terminal patients to decide when and how to die.

By the time he retired, Rasmussen had helped dozens of his patients end their lives. But he kept thinking about her. Alice’s pragmatism mirrored the image he had of himself and how he would face such a diagnosis. But while he had often conjured that image — had faced it every time he walked a dying patient through a list of inadequate options — he also knew better than to fully believe in it. How could you be sure what you would do before the decisions were real?

“You don’t know the answer to that until you actually face it,” he said later — after his own diagnosis had been made, after he knew that he had cancer and that he would soon die. “You can say you do, but you don’t really know.”

The knowledge hid in the back of Rasmussen’s mind — a flitting worry of the kind you don’t look at directly — for a few days before he really comprehended it.

He was on his way home from a meeting of the continuing-education group he had joined after his retirement. (Though he still practiced medicine at night in his dreams, he loved the chance to learn all the things he’d been too busy for during his medical career: particle physics, economic theory, world history.) One of the group’s members, a woman named Valerie, had asked him to let the others know that she had been diagnosed with a glioblastoma — a type of brain tumor, whose implacable aggression he knew well. A glioblastoma can cause seizures, nausea, memory loss, partial paralysis, even personality changes; one of Rasmussen’s glioblastoma patients confused his family when he lost all interest in bathing. You can treat the tumor with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, but it will always come back, often in more places. The timeline can be uncertain, but the prognosis never is. The median period of survival after diagnosis is seven months.

As Rasmussen drove away from the meeting, his left hand was draped on the wheel of his Tesla. It felt, as it had for several days, oddly numb, as if he’d been holding a vibrating object for too long. He’d ignored the feeling, chalking it up to spending too much time power-washing needles and pinecones off his cedar-shake roof.

Maybe it was what happened at the meeting, or the clarity of a wandering mind. All at once he focused on the sensation — on how localized it was, on the fact that it hadn’t gone away — and he knew. Something was wrong. It was wrong in a way whose ramifications he fully understood. “I’ve either got MS,” he thought, “or I’ve got a brain tumor.”

One of the things that he had come to believe about death was that hiding from it was a waste of time. He passed his own first test: his first thought after his realization was to wonder whether it was too late in the day to go to his doctor. Instead of driving home he went straight to an urgent-care clinic, where a doctor sent him to a hospital emergency room, where another doctor gave him an MRI, which showed a tumor. It was, he learned later, a glioblastoma about an inch in diameter. Barring an accident, it would be the thing that killed him, sometime in the suddenly too-near future. He was sixty-eight, and a lament floated through his mind: that he would most likely die before reaching his seventies. Sixtysomething sounded so young for dying. But he considered himself lucky that the tumor was in a part of his brain where it caused early symptoms, and that it was cancer at all — something whose progression he could predict and recognize.

Many doctors think of themselves primarily as healers, dispensers of drugs, even miracle workers, but Rasmussen was never one of them. Sometimes his physician friends would ask how he coped with the relentless loss of so many patients, but the truth was that he’d chosen his specialty precisely because there was so much death in it.

At the beginning of his career, when he worked as a primary-care physician in rural Maine in the 1970s, he sometimes felt like a glorified public-service announcement; he was forever telling people with hypertension to eat less salt. Treating dying patients for the first time was a revelation: the medical field had not yet fully embraced hospice or palliative care, and offering support in death was seen as inimical to healing. “We could give them a shot of morphine for a few hours of comfort,” Rasmussen remembered. “Otherwise, we just sent them home to die. It was terrible the way we abandoned those patients.” Making dying easier felt like a meaningful way to help, so he decided to train as a medical oncologist: “Medical oncology was the closest to caring for dying patients, because so many of the patients die.” He became board certified in hospice care and palliative medicine. Unlike many of his colleagues, he kept seeing patients after it was clear that chemo would be of no further use. He thought of his job, at its heart, as helping people to die — just slower and better than they otherwise would have. He moved to Oregon, set up a practice, and revived a local hospice organization, volunteering for years as its medical director.

Medical oncologists make the majority of their money from dispensing chemotherapy drugs — a common joke at conferences is that they stop only when they can’t pry the lid off the coffin — but Rasmussen often found himself discouraging patients from going through treatments that he thought would wreck the precious time they had left. “There’s a hundred percent chance of this hurting you,” he might say. “Maybe a five percent chance of success, and success means three more months.” But many patients seemed not to hear him. “Oh, there’s another chemotherapy I can do?” they’d ask. “Let’s do it.” He respected their wishes, but privately he told himself that he’d do things differently if the cancer were his: “I’m not one of those who will go grasping at straws for cures.”

At Salem Hospital, Rasmussen and others formed a medical-ethics committee, one of whose roles was to weigh in when patients, families, and physicians disagreed about which treatments the terminally ill should undergo. One day, several E.M.T.’s came to the group with a problem that Rasmussen later described as “one of the saddest examples of misguided medical legality” he’d seen. The E.M.T.’s were sometimes called to the bedsides of dying people, often by relatives in a moment of panic. Even if patients had advance directives requesting no CPR or their spouses objected, fear of legal repercussion forced the technicians to go ahead with efforts to resuscitate. They “had to do what they recognized as abusive to this poor, old, dying body,” Rasmussen remembered. The eventual solution, spearheaded by Oregon Health and Science University, was the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatments, or POLST, a legally potent doctor’s order enabling patients to avoid resuscitation. Brightly colored and meant to be hung prominently in the house, the POLST is now used in all but five states. Rasmussen was as proud of his part in the development of POLST as anything he’d done: “It saved who knows how many million dollars and how much heartache.”

In the early 1990s, the Salem Hospital medical-ethics committee faced a new question. The Oregon Death with Dignity Act — a law that would allow people with a diagnosed terminal illness to get a prescription for a fatal drug, which could only be self-administered — was headed to the ballot. At first Rasmussen wasn’t sure what to think of it. Like many doctors, he’d had plenty of patients over the years tell him that they were ready to die, to stop suffering — “I just want this to be over,” they’d say — but being the person who wrote the fatal scripts sounded like a terrifying responsibility.

He vividly remembered a patient he’d treated before the law was proposed, a woman in her fifties with both Alzheimer’s and a malignancy who told him she wanted to die.* The woman’s son was desperate to end his mother’s suffering. He’d read that a certain antidepressant that can cause cardiac arrhythmia was fatal in large doses, and he began to stockpile it. He told Rasmussen how much he’d saved, and asked whether it would work. Rasmussen told him that there could be unfortunate side effects, that it was untested, but that, yes, the drug might be fatal. The man’s mother took the drugs and spent hours in wild agitation before she died. “There was a whole lot of suffering in that death,” Rasmussen told me. “I obviously hadn’t helped in a way that I was satisfied with.”

Death with Dignity would provide a better option in such a situation, and Rasmussen believed that it needed to be discussed, at the very least. The committee began organizing debates at local churches, the library, and the Salem City Club. But there was a problem: “We could find no end of people who were willing to speak against it, but we couldn’t find any medical professional who was willing to speak for it.” Similar laws had already failed in Washington and California after opponents maligned them as the first step on a slippery slope toward death camps, and few doctors were willing to lose business by associating with such a controversial idea.

“Nobody else would step forward, and so Peter did,” said Joan Stembridge, a patient counselor at Salem Hospital who was a close friend of Rasmussen’s; she had helped start the ethics committee. “He wasn’t thrilled, he wasn’t eager, but he was willing.”

Some of the debates were ugly. “People would come up to the microphone and say, ‘I’m not dead yet!’ ” Stembridge told me. Doctors sent Rasmussen letters saying that he was a disgrace to the field of medicine. Patients, too, sent letters — one even scheduled an appointment — to tell him that they didn’t want him to be their doctor anymore. Some started seeing his partners instead, and avoided his gaze when they passed him in the hallway. Rasmussen imagined that he could hear their thoughts: “If he’s willing to kill patients, I wonder if I’m safe around him.”

The law passed with 51 percent of the vote in 1994, but it was stayed by a judicial injunction for three years before being reaffirmed by a higher margin of voters. When it finally went into effect, in 1997, there was no immediate demand for its provisions in Salem; only fifteen patients in all of Oregon used the law to end their lives during its first year. Many reported having trouble finding a physician who would write the prescriptions that the law had made legal. Patients from Salem told Rasmussen that he was the only doctor they could find who was willing to prescribe the fatal drugs; he struggled to locate pharmacists who were willing to fill the scripts. The hospice on whose board he had volunteered for so long would not accept patients with plans to make use of the law. For the first several years, Rasmussen had to send his Death with Dignity patients out of town for hospice services.

Rasmussen began as an ambivalent defender of the law, but the more he made the case for a patient’s right to die, the more he believed in it. In 2001, John Ashcroft, the U.S. attorney general, announced that assisting suicide was not “a legitimate medical purpose” and that any Oregon physician doing so would no longer be allowed to prescribe controlled substances. Rasmussen joined the state, a local pharmacist, and a group of terminally ill patients in a lawsuit to protest the ruling. After four years, the case was decided in their favor by the Supreme Court.

Within a few years, Washington and Vermont passed similar laws. Seventeen years after Oregon’s law went into effect, more than 1,300 people have gotten prescriptions and nearly 900 have used the drugs to die. The vast majority had cancer. Most died at home, and most said they chose the drugs because they feared losing their dignity, their autonomy, and the things that brought joy to their lives.

In 2015, legislatures in twenty-six states and the District of Columbia considered allowing some form of physician-assisted suicide. California’s version, which will become law this year, got a publicity boost when the family of Brittany Maynard, a twenty-nine-year-old woman with terminal cancer who ended up on the cover of People after announcing that she was moving to Oregon in order to use its Death with Dignity law, released a video of her advocating for a similar law in her home state. Maynard took the drugs in November of last year. Per the terms of the law, her death certificate listed her brain tumor, not the medication, as the cause of her death. It was a glioblastoma.

Eight days after his MRI, Rasmussen went to the hospital to have part of his skull cut away and his tumor sliced out. He had considered whether having surgery violated his usual advice about not wasting one’s final months seeking painful and unlikely cures, but because his tumor was localized and fairly accessible, he and his surgeon decided that the odds were good enough to try. Still, it was a risky surgery and he believed in being prepared, so before going to the O.R. he wrote his own obituary. “My Obituary,” he called it, and gave it the subtitle, “An Admittedly Self-Centered Tale.”

Rasmussen knew that his wife, Cindy, and his two adult stepchildren would write about his role as a husband and father, so he focused on the story of his professional life: the POLST, his hospice work, the fights over Death with Dignity. “This thing called life is quite a gas,” he concluded, “and mine has been filled with many advantages and good people. As an atheist since age 20 I hope that people will save their prayers for others, and use their money to help their neighbors across the street and across the world. I only hope that all can be as blessed and happy as I have been.” He filled out a POLST form and hung it on the refrigerator.

The surgery was a success — though Rasmussen lost the use of his left arm, the entire visible tumor was removed, and he was able to leave the next day. Of course, success was only a slower form of failure: he was still going to die. He never let himself, or anyone around him, forget that his reprieve was temporary. He tolerated no speaking of the abstract future as though he would be present for it, no euphemisms. “It’s not if I pass away,” he corrected his lawyer, his accountant, his friends. “It’s when I die.”

This didn’t mean that he was eager for the day to come any sooner than it had to. Chemo and radiation to keep the tumor from growing back right away were, in his case, reasonably good bets, and he underwent both treatments. Between them and the corticosteroid he was taking to keep pressure from building up in his damaged brain, he was frequently fatigued, nauseated, and weak. It was hard to get out of a chair, hard to climb the stairs to his bedroom, impossible to work in the elaborate flower gardens to which he’d devoted so much of his time since retirement. One day he took his dog for a short walk down the street and found himself too exhausted to make it home. He flagged down a passing car and asked for a ride.

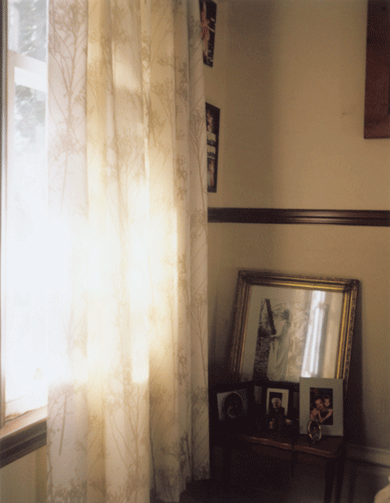

Before he retired, Rasmussen had often tried to help his patients and their families think of the process of dying as an opportunity, a chance for clarity and forgiveness, for thoughtful, meaningful goodbyes. (“That seems to be an important human interaction, to have that conversation.”) He hoped to hold on to that belief for himself, to think of his coming dependence not as a loss but as a chance to “experience a process different from what we’ve experienced all our lives.” When he pictured a good death, the image was simple: calm and peace, without much physical suffering, and his family with him in the house where he’d lived for eighteen years with Cindy, where the kids grew up, where the windows looked out on his bird feeders and his flowers.

It wasn’t time yet. Five months after the surgery, he stopped using the steroids and stopped the treatments. He began to feel better, stronger, and was even able to use his left hand a little. Still, every time he had a headache or nausea he wondered whether the tumor was growing back. Sometimes he got lost in sadness or worry, but he tried to think of those moments as transient accidents, something to snap out of. Whenever he started to feel sorry for himself, he’d administer a stern mental shake: “We all die,” he’d tell himself. “It’s never fair to anybody. So buck up.” He didn’t go to therapy. “I don’t think I need it,” he said. He knew he was in good shape, statistically speaking, with family and friends to lean on and no major financial stress accompanying his death. Besides, he laughed, “I’m one of those strong, silent people. They’re usually the worst.”

He talked to his family about what he was willing to endure in order to stay alive. Some of his patients had loathed being bedbound, and considered it the ultimate indignity. Though he was pretty sure that with his stubborn independence he’d hate it, too, he felt that he’d be able to handle it. He’d still have access to books and lectures, to his friends and family, and as long as he wasn’t in a lot of physical pain, those things would be the barometers of his quality of life. He appeared as an expert witness in Canada, where in February 2015 the Supreme Court cleared the way for physician-assisted suicide, and he wrote an op-ed for the Sacramento Bee supporting California’s physician-aid-in-dying law. “Personally,” he wrote, “I take comfort in knowing that when my glioblastoma produces symptoms that can’t be controlled by even the best hospice care, as an Oregonian I will retain the final human dignity of control over the circumstances of my death.”

Privately, he had no idea whether or not he’d take advantage of the law. It depended on how his tumor and symptoms developed, of course, but also on a version of himself he had yet to meet. He consulted a list that he’d begun to keep of his Death with Dignity patients once it became clear there were going to be more than a few dozen of them. At first most were urgent cases: people with all kinds of terminal diseases, not just cancer, who were suffering intensely and wanted to take the drug right away. As time passed, people began coming to him sooner after their diagnoses, before they knew how their diseases would develop. Death with Dignity was one of a list of options they were looking into. Some only asked questions, some prepared the forms, and others wanted to have the pentobarbital handy, a just-in-case comfort that made them feel more in control. The majority of his patients never took the medication. Still, by the time he retired, he had helped about sixty of his patients end their own lives over the course of a decade.

Every death was different, though most had details in common: reminiscing in advance, goodbyes filled with love, family members offering permission and saying that it was okay to stop struggling. He wanted to remember it all — and especially the people who had navigated those deaths, some of his most remarkable patients — so he held on to piles of charts. Now, a little more than a year after his surgery, he found that they also offered lessons, reminders of how others had faced their own harsh decisions. He pulled thick stacks of folders from their white plastic wrapping and spread them out on his dining-room table. He flipped through death certificates and photos and his dictated accounts of home visits and forms labeled “Request for Medication to End My Life in a Humane and Dignified Manner” — all the official detritus of dozens of complex deaths.

There was the death with the Harley-Davidsons: that was a good one, he thought. He’d pulled up to the house and there were motorcycles everywhere, people in leather drinking beer on the lawn, just the party his patient wanted.

Of course, not everyone wanted a party, and he respected that too. Often there were only a few family members, and sometimes it was just him and the patient, alone together at the last. Only once did someone ask to die completely alone, in quiet privacy behind the closed door of a bedroom.

He remembered a woman whose bilateral mastectomy had not stopped her breast cancer from metastasizing to her lungs. Her huge family came in for the weekend. They had a picnic on Saturday, went to church on Sunday, and then all the kids and grandkids filed through her bedroom to say goodbye. He waited outside the door until they were done and then he brought her a dose of pentobarbital. She drank it and died. That one stuck with him: “It was about as ideal a death as I possibly could have imagined.”

There was a woman with a brain tumor who ended her life in the summer of 2003. She was a favorite of Rasmussen’s: “She knew what she wanted and didn’t want,” he remembered. “I was impressed with her. She didn’t want to just linger on.” There was a Korean War vet who believed he’d been living on borrowed time ever since a shell landed between his legs and failed to explode. His photo shows a white-haired man with glasses and an oxygen tube staring frankly into the camera. “He is quite comfortable with how his life has proceeded,” Rasmussen wrote. “He is spiritually at ease.”

Many patients practiced swallowing six ounces of fluid to be sure they could drink all the medication. In each case, Rasmussen checked off the requirements of the law: “He has been fully informed of his options and possible treatments,” he might write. “He seems to be under no duress. He is appropriately sad at the loss of his strength and vitality and sad about his impending death, but there is nothing to suggest that he has clinical depression that would be prompting him to seek a suicide.”

He received a notice from the assisted-living facility where one patient was living, warning him that physician aid in dying was strictly prohibited anywhere on the property: “We feel this could ruin our reputation in the community.” The patient had requested a script, but two weeks later the request was withdrawn. Rasmussen believed that the facility’s staff had talked him out of his decision.

Rasmussen pulled out a Polaroid of a man in a blue sweater-vest sitting in front of shelves of medical supplies. He died in the hospital two months after being referred to Rasmussen. “I think I did him no good at all except helping him and his family be comfortable with discontinuing life support,” Rasmussen said. He remembered a long discussion among the man’s extended family before someone finally asked the patient what he thought. He was emphatic: he was ready.

Rasmussen could relate, in a way. Though he was glad to be doing so surprisingly well — well enough, even, to plan a trip to Scandinavia with Cindy, his stepdaughter, and her husband — it was hard to have his future, at once certain and uncertain, hanging over him. In a strange way he looked forward to the tumor’s inevitable return: It would be a small relief, he thought, to know more about what awaited him.

Two days after coming back from Scandinavia, in July of last year, Rasmussen went in for a new MRI. The scan showed the tumor, the same size and back in the same place it had been the year before. He consulted with his surgeon, who told him that the tumor was once again a good candidate for removal. They could even take out the same portion of skull. There would be pain and weakness and discomfort and Rasmussen would most likely lose the use of his left arm altogether, but if all went very well, he would have a one-in-three chance of living to the second anniversary of his diagnosis.

“I’ll leave tomorrow for the trip,” he told Cindy immediately after meeting with the surgeon — meaning a cross-country road trip that he’d been talking about, to try out his Tesla over long distances and to drop off his stepdaughter’s dog at her apartment in New York City. Cindy was stunned. She hadn’t thought he’d actually go, much less that he’d go with one day’s notice and before talking to other specialists about his options. But he was adamant, and then he was gone.

He drove east through Idaho, Montana, South Dakota, along long, open stretches of quiet road. He brought recorded lectures from his collection to keep him company on the drive: one about the life of St. Francis, a series on the Higgs boson, and a particularly interesting lecture about gnosticism. Despite his committed atheism, he liked learning about early Christians’ efforts to reconcile Aristotelian logic with their beliefs: “It shows how people will go to great ends to explain what they’re thinking.”

As he drove, he tried to visualize what his life would be like if he underwent surgery or radiation or chemo or stopped treatment altogether. He imagined losing more of the use of his left side — he worried that he was beginning to lose his left foot already, and sometimes felt like it was sliding away from him as he crossed hotel lobbies — and eventually ending up in hospice, bedbound.

That part didn’t bother him so much. He knew it was coming no matter what. But he didn’t like thinking about stopping treatment, not yet. It was too passive, too final. It just made him too sad.

Somewhere around the ninth day of his trip, as he neared home, he had a thought that excited him. “The task of learning to be a hemiparetic person,” of living with paralysis on his left side, could be an adventure, another learning experience, one final thing to accomplish. “So many of the options are really kind of bleak,” he explained later, “but to take on a challenge is always satisfying.” Relief washed over him. He could stop the internal debate. He had made a decision.

He wasn’t planning to have the surgery right away, but an hour after arriving home he had a seizure that spread from his left eye to his entire body. Four days later he was back in the O.R., and surgeons were once again scooping a tumor from his brain. He woke to find himself paralyzed not just in his arm, as he had expected, but throughout the left side of his body. For days he was noticeably quiet. It was a shock that neither he nor Cindy had planned for; they hadn’t even thought about preparing the house for that level of disability. After three days he moved to a nursing-care facility. The first morning there, he called Cindy to tell her that he’d been very sad the night before. After eighteen years of marriage, Cindy was surprised to hear him talk about his feelings unprompted. “Did you cry?” she asked.

“No, I didn’t cry,” he replied. “But I was mourning the loss of my independence.”

He assured her that he had come to terms with the loss. She thought that he might regret having the surgery, but Rasmussen insisted he didn’t. She visited him every day, and together they celebrated little victories — involuntary movements in his hand and leg, the return of his appetite, taking his wheelchair into the building’s little garden — and focused on the immediate future, the goal of getting him back home. “To have to watch him like that, just struggling to sit up in bed, it’s really hard,” she said. “For someone who’s used to being so independent, this is a very difficult thing.”

Ten days after arriving in the facility, Rasmussen lay in his room across from the nursing station. Its walls were decorated with shots of his Scandinavia trip and of the koi pond in his front garden, both of which seemed far away.

“Progress seems so scant, so slow,” he said after a morning during which he’d worked with a physical therapist to practice rolling over in bed and sitting up without falling. “It’s turning out to be much harder than I thought.” Then his internal pep talk kicked in, and he added, “But I’ve had such a good life. I’m satisfied with it.” His voice broke, just barely enough to notice. In the previous day’s paper he had seen the obituary for his friend Valerie, the one from the continuing-education club whose glioblastoma was diagnosed just before his.

Before heading into surgery he’d bought several series of educational DVDs to prepare for the downtime that he knew would follow. One was about the American Civil War, another about the history of Africa. “I’m still curious about things, so that’s good,” he said. “That’s part of your quality of life,” Cindy told him.

The phrase had become a touchstone, to be monitored alongside his temperature or blood pressure. “If there is any reasonable quality of life, I want to continue life,” Rasmussen said a little later, lying back in his hospital bed. “Life is hard to give up.” For more than a year, there had been two things about the future that he felt he could know for sure. One was simple: “It’s still all going to come to a crashing end at some point.” The other thing, more complicated now than ever before, nevertheless remained true: when the end came, he said, “I have the courage to let go.”

In the afternoons, he got his daily shot in the stomach, a drug to keep his blood from clotting while he was immobile. An occupational therapist helped him practice taking a shirt on and off with one hand. Then she helped him slide along a wooden board to move from the bed into a wheelchair. “Are you tired?” she asked. “Are you feeling dizzy?”

“Just a little bit,” he replied. The strain was evident. “But let’s keep going.”

Down the hall in the therapy room, he practiced his balance, moving colorful plastic cones from his left side to his right with his good arm as Cindy and a visiting niece cheered him on. “We’re ready to watch him do cartwheels,” Cindy said. “Or face-flops,” he replied.

Sometimes he came close to falling over, and the therapist would catch him. Sometimes he paused mid-movement, marshaling his strength for the next effort. But every time the therapist gave him an out, a chance to quit, he shook his head. “I can do more,” he insisted.

“You’re pretty brave,” Cindy told him, referring to his decision to undergo surgery and embrace his paralysis.

“Well,” he said, “the options were kind of limited.”

A week later, both of his stepchildren came in from out of town to celebrate the seventieth birthday he hadn’t expected to see. With Cindy, they surprised him in a conference room of the nursing center, bringing pizza and a pie and a dozen of his friends. Rasmussen blew out the candles and felt hope: there was slight muscle action on his left side, and he’d been advancing in rehabilitation. Ten days later he was strong enough to move to a rehabilitation center in Portland for more intensive therapy, several sessions a day, with the goal of living independently again, under Cindy’s care.

As his “graduation” date approached, Cindy and a pair of therapists took him out in his wheelchair for dinner in downtown Portland, a practice run for the modified normal life he was training for. They took him to the assisted-living facility where he would soon be going. He and Cindy also visited the wheelchair-accessible house they planned to borrow from friends who were out of town for six months. Cindy practiced moving him from his wheelchair into a car, onto the non-hospital beds, onto the commode. It was late September and the weather was beautiful. “We both felt like — yeah! We can do this,” said Cindy.

In retrospect, though, that weekend was the beginning of the end. Rasmussen slept the whole way back from Salem. He still seemed exhausted days later. He moved to the assisted-living facility, but within a day it was clear that he needed more care than could be provided there. He began saying things that didn’t quite make sense; he seemed to think he was at the therapy center. Later in the day he remembered his confusion and was afraid. Throughout all that had happened, he’d always stayed sharp. This was new.

On October 1, he was admitted to the hospital for a new MRI, one he hadn’t expected to need until the spring. He moved back to the nursing home that he’d left excitedly a few weeks before and waited for the results. They showed that his tumor had not only grown back but expanded into the middle of his brain. The next morning, Rasmussen’s friend Joan Stembridge found him at the facility, not eating or drinking. “I want to go home and have hospice,” he told her.

He returned not to the wheelchair-accessible house but to his real one, where Cindy set up a hospital bed in the living room looking out over his gardens. His stepchildren arrived from New York and Seattle. Rasmussen asked about taking secobarbital, and Cindy and Stembridge exchanged a look. They thought he was too close to death to need it, and possibly too weak to swallow it. For four nights Cindy and the kids stayed by his bed, each night thinking it would be the last. Instead, he grew stronger for a time — a month that Cindy calls “one of the most meaningful experiences I’ve ever had and probably will ever have.” He visited with friends and family, watched a slide show of old pictures, listened as music therapists, brought in through his old hospice program, played his favorite songs on his favorite instrument, the ukulele. Cindy and the kids sang along just as they used to when he could still play. They turned him every few hours to prevent bedsores. He ate small bites of food and sipped juice or water or beer. When he wanted ice chips, he had a joking gesture: whirling the index finger of his working hand imperiously in the air.

Rasmussen had already started the paperwork for Death with Dignity, getting the approval of two doctors, but he didn’t want to add the final touch, his own signature. Near the end of October, he was speaking only a few labored words at a time. One day he asked Cindy to help him stand so he could get up to go to the bathroom, something he hadn’t done in weeks. He was so weak and frail that Cindy told him it was impossible. She says she saw the realization happen then: “This is it.”

On October 29, Rasmussen signed the paperwork and asked Cindy to call his siblings, who flew in from Wisconsin, Illinois, and North Carolina. He planned to take the drug the next week, after what Cindy calls “a memorial service while he was still alive.” Stembridge asked the minister from her Unitarian Universalist church to facilitate it. Sixteen people gathered around Rasmussen; one by one they told him what he had meant to them and what they would remember about him after he was dead. Rasmussen was drowsy — he’d had a seizure earlier in the day and had to take a sedative to control it — but he managed eye contact and a few whispers.

He was alert but not talking much on the morning of November 3. His family intertwined their arms in a circle around him and put piano music on the stereo. He raised the cup of secobarbital mixed with juice — papaya, orange, and mango, his favorite — and drank it down. His eyes closed. Cindy, sobbing, realized how similar the scene was to what he used to describe when he came home from someone else’s death. “It was awful,” she says. “But at the same time, I was glad that he was able to end his life on his terms.”

Half an hour later, he quietly stopped breathing.