The Wooster Group, an experimental-theater company in New York, has been doing its ludic, fevered work for forty years now. Though its shows, in description, can sound like bad ideas that some smart graduate students came up with at two in the morning, in performance they are almost always very funny, and also an encounter with serious, enduring art. Often they reimagine canonical works. Sort of. House/Lights paired Gertrude Stein’s Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights with Olga’s House of Shame, an old B movie. The Emperor Jones, by Eugene O’Neill, was staged with Kabuki-like dance interludes and featured the actress Kate Valk, in blackface, as the male lead. Hamlet was performed with, and against, an edited film of Richard Burton’s 1964 Broadway production, which was shown on screens for much of the Wooster version. Valk played both Ophelia and Gertrude, while Scott Shepherd, as the prince, called out to fast-forward, pause, or skip scenes.

When I saw their Hamlet, in 2007, I was, I confess, filled for the first twenty minutes or so with a longing for “ordinary” Shakespeare. But after the dulling effects of expectation and familiarity were killed off, the similarities between Ophelia and Gertrude began to make new sense; Shepherd’s quiet and somewhat distracted delivery of the “To be, or not to be” speech paradoxically made the words feel freshly meaningful; and by the end of the show, I felt as if, for the first time, I had glimpsed the play’s true spirit. It was the best Hamlet I have ever seen. The Wooster performers are clowns running a séance. What’s wondrous strange is that the ghosts reliably turn up.

The Wooster Group is now engaged with Harold Pinter’s first play, The Room, which previewed at the Performing Garage, in New York, in October and opened in February at REDCAT, in Los Angeles. I was curious what the group might do with Pinter, who has one of the most recognizable styles of the past century. His work is known for its bated violence, and for its tense, often funny dialogue, although the audience rarely understands the sources of the tension, and the characters rarely understand that they come off as funny. Pinter’s plays are also renowned for their pauses, which are written into the stage directions; these silences seem to occupy the space where, in the past, a Greek chorus might have interjected.

First performed in 1957, The Room is a one-act black comedy, with all of comedy’s familiar features: misunderstandings, callbacks, innuendos, and arguments about whether or not to sit in a particular chair. It was written in just a few days, and the uninhibited energy of its creation was channeled into a deeply elemental structure. A woman, Rose, lives in a rented room, in what seems to be lower-middle-class England in the 1950s, with the nearly silent Bert. After Bert goes out, a young couple looking for a place to live drops by; they seem to want Rose and Bert’s room. Later, another stranger, an old “blind Negro,” visits. But the stranger doesn’t really seem to be a stranger; he calls Rose “Sal” and asks her to come home. After Bert returns and gives a bizarre speech (strongly reminiscent of Lucky’s in Waiting for Godot), he brutally beats the visitor. In a sense, the one-act’s structure is formal and classic — who’s in the room, who’s not, and is all that menacing darkness coming from within or without? The tropes are ancient: a stranger comes to town, a traveler returns.

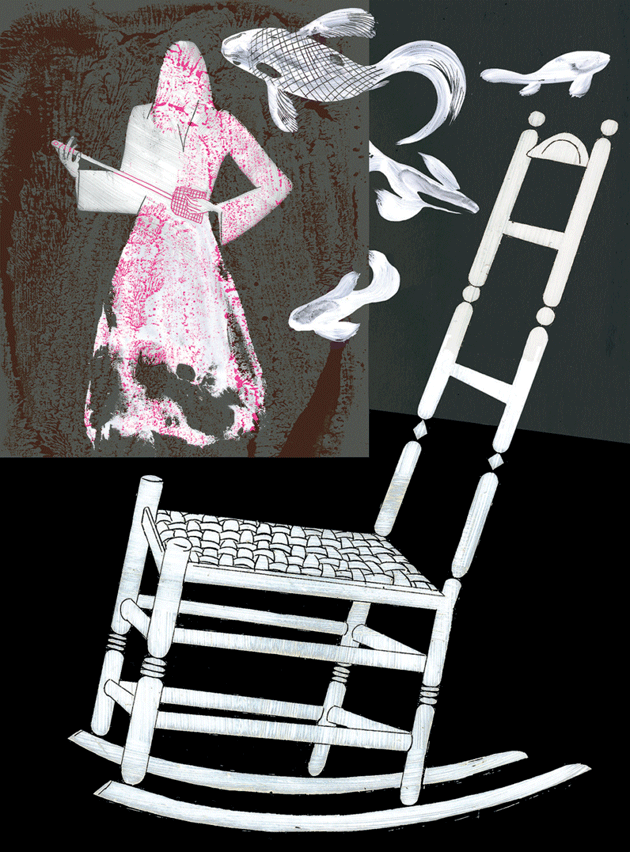

In the Wooster Group’s production, the shabby, naturalistic setting has been transformed into something altogether different: the kitchen sink center stage trails a pipe leading to nowhere, the television screens that are partially visible to the audience show what appear to be Chinese political debates, and Kate Valk, the actress who plays Rose, uses a flyswatter as a ukulele while she sings some of her lines in a tonal pattern that recalls the koi ponds one visits only in imagination. The stage directions are spoken aloud by the actors, which means that each of Pinter’s pauses is announced. The video footage is actually “crosstalk,” a kind of two-man stand-up comedy that the Wooster Group came across in its recent travels through China. While performing The Room, the actors wear earpieces that pipe the crosstalk dialogue — in its original Chinese, which none of them understand — among other things, into their ears. So the actors “surf” (their term) the speech patterns of the foreign comedians, which leads to odd cadences and surprising emphases.

Somehow it works. Consider one characteristic pause, when Rose breaks the tension that has accumulated between her and her unexpected guests by taking up the man’s mention of his wife’s name:

rose: Clarissa? What a pretty name.

mrs. sands: Yes, it is nice, isn’t it? My father and mother gave it to me. [Pause] You know, this is a room you can sit down and feel cosy in.

The awkwardness interrupted by the pleasantry — “What a pretty name” — is immediately revived by Mrs. Sands’s confusingly obvious elucidation. The pause that follows her statement is typically comic; since no one onstage remarks on the oddness of what Mrs. Sands has said, a gap is left for the audience to inhabit. This works beautifully in almost any performance of The Room; it got a laugh in the Wooster Group show too. But the actors’ crosstalk surfing introduces other pauses. These erratic silences come not from Pinter’s studied psychology but from somewhere more subconscious — a trace phenomenon that results from an actor trying to follow the script and the crosstalk at once. They make The Room feel vital again, and, perhaps surprisingly, more psychological — more evocative of the automatism and unintentional emotional disclosures of everyday life.

In other productions of The Room, some of the comic dialogue comes across as portentous, as when Rose says to Bert, “It’s very cold out, I can tell you. It’s murder.” In the Wooster Group production, these lines still attract attention, but other, softer lines also insist on themselves. A remark as simple as “We’ve not long come in” has stayed with me. The words seem to carry the weight of civilization: we human beings have not long come in from the wild. (Such thoughts need silliness to keep them honest and bearable, and that, I think, is where a flyswatter that doubles as an air ukulele helps.) Because these lines register as both substantive and slight, they gain access to the normally highly guarded emotional space of the theatergoer. The it’s-just-a-play barrier falls away, in part because the performers have taken on the burden of saying “It’s just a play” for us; they are, after all, reading the stage directions aloud.

But what can those simple Pinter lines mean? The Room is clearly “about” class and race in midcentury England, but the play has mythic qualities as well. The Wooster production, even with its conspicuous earpieces, felt like a conjuring of nervous Neanderthals (or postapocalyptic humans) who are not yet accustomed to reliable shelter. It seemed to take place simultaneously under a ginkgo tree millennia ago, in England in 1957, and in a goofy sacred garage in Manhattan. The only special note in the program mentions the company’s drive to pay for the heating and cooling system that was recently installed at the Performing Garage; so much effort goes into basic physical comforts, into finding a serviceable roof and four walls. The program offers no explanation for the crosstalk. Elsewhere, Kate Valk has explained:

A lot of how we work, with the in-ear tracks and the cues off the televisions, keeps us responding in the moment, shortening the time between impulse and action, so what we do is cued from this outside stimulus. And that can keep changing, so there is the potential for the unpredictable.

It’s as if being too attentive to the actors’ methods would be like taking their breakfast habits or working heart rates too seriously; external stimuli may fuel their performances, but they don’t explain them.

Still, Wooster Group productions tend to bring out our anxious clue-seeking drive. Obeying this instinct is occasionally thrilling. In The Room, Valk wears a strange sort of padded pouch, which looks like a cross between a misplaced bustle and a fanny pack, around her waist. Such pouches, sometimes used by other theater companies to alter the shapes of performers’ bodies in more conventional costuming, often appear in Wooster productions in ways that don’t seem to refer to any probable anatomy. Seeing these lumpy appendages evolve over time — sometimes they serve as sexual accessories that are petted and stroked, sometimes they are just weirdly there — is moving in an unexpected way. In this production, in which Rose speaks at length to a man who offers no words in return, the pouch almost seems like a visual manifestation of the unspoken emotional energy onstage.

In trying to follow the Wooster Group’s meanings over the years, I have come to think of them in relation to one of the stranger moments in the New Testament, when Jesus explains the parable of the sower to his disciples. This is the one about a farmer sowing seeds — some get eaten by birds, some land in rocky soil, but some find fertile ground and produce a good crop. When the disciples ask the meaning of the story, an irritated Jesus explains that the seeds are the Word of God, the varieties of soil are the varieties of people who hear the Word, etc. The story means just what it sounds like it means.

Is it really a parable, then? Religious and academic commentators have offered many thoughts about this passage and about Jesus’ claim that he speaks in parables so that only the initiated will understand him — a troublesome idea to many Christians. And to many theatergoers. Shouldn’t meaning be simple and clear? For myself, I like the idea that Jesus’ straightforward parable and exegesis are both about seeing the surface of what is right there — the surface is the depth. Wooster Group shows are, in their way, exceptionally faithful to their sources. In its Hamlet production, the group restored and emphasized the iambic pentameter — Scott Shepherd paused at the ends of lines, not of sentences — and it edited the Burton film to follow the same cadence. Many Pinter productions deal with his pauses, which are now almost too famous, by leaving them out — an approach that Pinter himself endorsed. But the Wooster Group, of course, leaves out none of them. True nonsense is fragile, and it follows stricter rules than the sense that it obliquely describes. The Wooster Group puts on shows that feel inevitable and random at once. They don’t translate, resolve, or grow outdated. The best response to their wondrous strangeness might be that recommended by a Danish prince more than 400 years ago, in an English play that was based on a story that had itself already been around for 400 years: as a stranger, bid it welcome.