Hail, Caesar!, the new film by Joel and Ethan Coen, starts and ends with a confession and a slap in the face. The movie covers a day in the life of a production chief at Capitol Pictures, who is played by Josh Brolin. The Coens have named him Eddie Mannix, after a real Hollywood fixer who spent his career cleaning up the messy personal lives of MGM’s stars so that scandal would not hurt the box office. But Mannix’s confessions, which bracket Hail, are not the kind that turned up in the gossip rags of 1951, the year in which the film is set — they take place in an actual confessional.

Mannix’s first order of business, after a predawn visit to his priest, is to rescue a starlet named Gloria DeLamour (Natasha Bassett) from a “French postcard situation” before the cops appear and the story leaks to the press. She balks at Mannix’s intervention, and he slaps her to make her listen to the story he has concocted for the police. Gloria is dressed as an Alpine milkmaid, but when the officers arrive to bust up her cheesecake tableau, Mannix explains that “it’s not really her dirndl.” He couldn’t care less about the threat to her virtue; it’s the threat to her virtuous image, and that of the studio she represents, that has him out of bed so early.

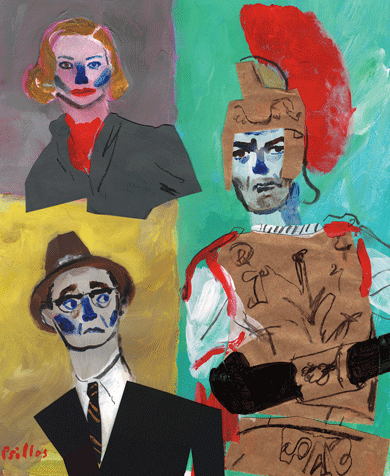

The end of the film reprises the opening, with one important variation. This time Mannix cuffs the star Baird Whitlock (George Clooney), who, dressed as a Roman centurion, is in the midst of explaining how the studio is a microcosm of the exploitative capitalist economy. He has picked up this line of thinking from a group of Communist screenwriters — modeled on the blacklisted Hollywood Ten — who have been holding him captive in a Malibu beach house. When the hyper-scrupulous Mannix returns to the confessional, a mere twenty-seven hours after his first visit, he admits to striking Whitlock, but not DeLamour. Slapping a leading man is a mortal sin, requiring forgiveness. Slapping a starlet is not worth mentioning.

The recipients of Mannix’s tough love are in costume for a reason: a cast system determines how they dress. Whitlock — the star of Hail, Caesar!, the epic film within a film that is Capitol’s Spartacus — wears his centurion outfit because he was nabbed from the studio’s back lot. The uniform indicates his rank in Hollywood no less than it does in the fictionalized Rome of Hail, Caesar!, and it is the only clothing Clooney wears in the movie. Gloria DeLamour, of lesser importance, is dressed as a peasant because, by Hollywood standards, that’s what she is. Two extras in the film within a film (Wayne Knight and Jeff Lewis) set the kidnapping in motion by spiking Whitlock’s prop chalice with knockout powder. The extras, Hollywood’s lowest of the low, are dressed as Roman slaves. All of the actors are always in costume, and none of them own the clothes they wear.

Commie talk is not confined to Hail these days. A specter is haunting Hollywood once again — the specter of the 1950s. Ever since the idylls of Grease (1978) and, on TV, Happy Days (1974–84), each era has reimagined the high-water-mark decade of the American Century for its own purposes. During the Reagan years, movies such as Back to the Future (1985) presented the Fifties as a lost Eden. In the age of Clinton, we were sold an overpriced box-set version that leaned heavily on the slick style of the Rat Pack and the young Elvis, which was transmogrified into the present by movies such as Swingers (1996). That image soon dissolved into the sleazy Fifties of James Ellroy’s novels and the screen adaptation of his L.A. Confidential (1997), in which the swagger and polish was exposed as a facade. The cynical vision of the era peaked in Mad Men (2007–15), which saw Don Draper mask his glib predations under an assumed identity that he’d stolen on the battlefields of Korea, America’s forgotten war.

These days, it is the Fifties of the Red Scare — the years of the blacklist in Hollywood and the Rosenberg trial in New York, of Communism, anticommunism, and anti-anticommunism — that is being revived. This makes a certain kind of sense, given the privacy concerns, socialist passions, and open ideological combat of our moment. Indeed, the most recent films about the Fifties — Bridge of Spies, Trumbo, Carol, Brooklyn — are suffused with confusion and scared conformity. Authority is pervasive, interfering in people’s personal lives, bossing them around.

Hail, Caesar! belongs in this company, up to a point. The Coens have turned the Ellroy Fifties inside out; the scandal and corruption on which the plot of L.A. Confidential hinges are a given in the world of Hail — grist for comedy, the prerequisite for a happy ending. The Coens’ Hollywood is an empire, where fraud is cheerful, natural, invisible — where people can live as they want to, so long as they don’t trouble the system that keeps them employed. Everything goes fine there until the Commies show up.

In many respects, however, Hail is atypical of the current crop of Fifties movies, which, for all their paranoid atmospherics, tend to be more optimistic and earnestly liberal. Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, which opens in 1957, is about a prisoner swap between the United States and the Soviet Union that took place in Berlin. James Donovan, the fixer figure played by Tom Hanks, was a real person, not simply a character with a real person’s name. The film grapples with themes of global significance in a manner that makes it feel like an unironic version of Hail, whose hostage scenario — and the ideological conflict behind it — is played for laughs. The Coens — who wrote the script for Bridge of Spies along with Matt Charman — show a sarcastic disregard for the leftist screenwriters who kidnap Whitlock (never mind that the real Hollywood Ten served jail time for their political beliefs), but Spielberg’s film is deeply sympathetic to the plight of Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance), a convicted KGB spy who worked from an apartment in Brooklyn. Rylance, who won an Oscar for his performance, plays Abel with great solemnity, as a man who is caught between two worlds, both of which would rather see him dead.

The plot of Bridge of Spies revolves around the downing of a Lockheed U-2 spy plane and the Soviet trial of its American pilot, Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell), who was eventually swapped for Abel. Lockheed shows up in Hail as well, in the person of a company executive (Ian Blackman) who is trying to tempt Mannix away from Capitol Pictures with a job offer. Mannix sneaks off from work to meet him in a noirish Chinese restaurant with boothside fish tanks reminiscent of the Book of Jonah water ballet in the film’s Esther Williams–esque musical sequence. The whale about to swallow Mannix here is the defense industry. The Coens contrast the frivolity of Hollywood with the seriousness of nuclear Armageddon and the geopolitics that animate Bridge of Spies. The Lockheed man, with his wallet photo of a mushroom cloud and his talk of the H-bomb (“the H-erino!” he calls it), sounds nuttier, and far more dangerous, than the people Mannix already deals with for a living.

Trumbo, which stars Bryan Cranston as the blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, features several actors (John Goodman, Michael Stuhlbarg, Stephen Root) from the Coens’ stable. Its examination of Hollywood under the blacklist is manic if not madcap, with Cranston’s pro-Soviet Trumbo standing up for Communist values and beating the system on his own terms. Trumbo is the writer who, with the help of Kirk Douglas, broke the blacklist, which allowed him to receive screen credit for his work on Spartacus (a film that happens to be playing in the West Berlin of Bridge of Spies).

Todd Haynes’s Carol sets the visually exquisite surfaces of its imagined 1952 against the harsh story of lesbian lovers who are denied the freedom to be a couple. Men treat Carol (Cate Blanchett) and Therese (Rooney Mara) the same way the FBI treated suspected Communists in the HUAC years, stalking and spying on them. (Carol’s husband is gathering evidence for a divorce settlement.) In fact, there was also a Lavender Scare in the 1950s, during which McCarthyites sought to out left-leaning gay people working in the U.S. government. John Crowley’s Brooklyn, meanwhile, about an Irish girl (Saoirse Ronan) coming of age in County Wexford and in New York City, and also set in 1952, is a milder version of this — a Redhead Scare. Here, the dinner-table talk of Communist spies and loyalty to bosses foreshadows the way the girl’s former employer will threaten to expose her secret marriage and ruin her life.

The women in Carol and Brooklyn find ways to survive. They learn to accept risk and uncertainty so that they can live the lives they want. In Trumbo and Bridge of Spies there are, as Dalton Trumbo said in a speech used at the end of the film, “only victims” of the Red Scare. The men in this version of the Fifties are aging and battered. Even George Clooney looks tired of playing a Roman. He would rather kick back with the Communists.

After Roland Barthes watched the 1953 version of Julius Caesar, which starred Marlon Brando, he wrote that he saw in the faces of the movie’s Romans “the Yankee mugs of Hollywood extras.” When epics such as Spartacus were made in the 1950s, the audience was expected to identify with the early Christians, not the conquering Roman army. The conflict between empire and uprising, which was often linked to Christian faith, plays out in Hail too, in which it is the extras who try to start a revolution. They fail because, like so many other would-be world-beaters in the Coen oeuvre, such as the nihilists in The Big Lebowski, they are schmucks in cahoots with other schmucks. The Communist screenwriters they work for are so inept that when last we see them, meeting a Soviet submarine off the shores of Malibu, we find out they literally can’t handle money: a suitcase full of ransom cash falls out of their hands and sinks into the ocean.

The submarine descends back into the Pacific and back into Hollywood’s unconscious, the fantasy of a future that never came to pass. Hail is a comedy of stasis in which a new, sunnier Coenian cynicism rules. Mannix reaffirms his belief in the system (the studio system, that is) and restores its functioning order. All is for the best in this best of all possible make-believe worlds. Yet the Coens’ vision may not be as witheringly post-ideological as it first appears; the possibility of a Pauline conversion or a Spartacist slave revolt lingers after the movie ends. DeeAnna Moran (Scarlett Johansson), the film’s ironic Virgin Mary, even carries a fatherless potential savior — but a savior of what? Baird Whitlock is briskly disabused of his newfound Marxism by Mannix, who orders him to return to the set. Back on the job, however, Whitlock cannot remember to say the word “faith” at the end of his culminating speech in the film within a film. His blown line breaks the surface of the spectacle, pulling the audience out of both films, if only for a moment. When Mannix is told that the movie’s final word is not working, he offers a suggestion for finding a new one. “Bounce it off the writers,” he says, setting the dream factory in motion once again.