Years ago, I lived in Montana, a land of purple sunsets, clear streams, and snowflakes the size of silver dollars drifting through the cold air. There were no speed limits and you could legally drive drunk. My small apartment in Missoula had little privacy. In order to write, I rented an off-season fishing cabin on Rock Creek, a one-room place with a bed and a bureau. I lacked the budget for a desk. My idea was to remove a sliding door from a closet in my apartment and place it over a couple of hastily cobbled-together sawhorses.

I sought help from a Mexican-American buddy named Freddy. We lashed the closet door to the roof of my car and drove twenty miles out of town toward the head of Rock Creek. Midway there, a gust hit the front of the car, lifting the closet door with enough force to snap the rope. The door flew onto the side of the road and I steered to the shoulder. Freddy and I walked to the ditch. My future desk was now bent in the middle, not quite broken but splintered to ruin. Freddy shook his head.

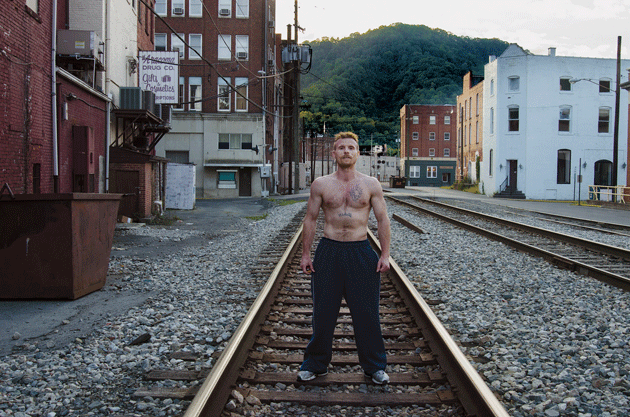

“Pine Mountain, Kentucky, 2016,” from Speak Your Piece, published by Here Press in September. All photographs by Stacy Kranitz from her ongoing series on Appalachia

“Things like this don’t happen to guys from Connecticut,” he said.

We knew it wasn’t strictly true. Bad luck happens to everyone, even in Connecticut. Still, I understood what he meant. Neither of us was a WASP, benefiting from the convergence of class, religion, race, and place. As educated American males we both had a leg up, and I was white, a boon in the grand scheme of life. In Montana, however, we banded together because cowboy culture didn’t suit us. Neither of us skied, hunted, fly-fished, rode horses, or herded cattle. I could pass easier than he could, but Freddy and I were always the odd men out.

That incident ran through my mind recently as I considered the changes that have taken place in rural America since I was a child. Country life differs greatly from state to state. Geography dictates industry: mining, logging, farming, or ranching. Each produces its own set of cultural values. The Kentucky hills where I grew up yielded clay that was ideal for the manufacture of heat-resistant bricks used in kilns and furnaces. My hometown of Haldeman began as a business enterprise, in 1903, that mined clay, turned it into firebricks, and shipped them to northern steel mills. For several decades, the place flourished: there was a train station, a barbershop, a tennis court, and public gardens. Then the workers attempted to unionize, and a “labor uprising” at the Kentucky Fire Brick Company in 1934 was big enough news to make the New York Times, which reported that the National Guard had been sent in. Eventually, the owner sold Kentucky Fire Brick, along with the town itself, to U.S. Steel, which closed down the operation in 1951.

By the time I came along, Haldeman was a zip code with a creek. Two hundred people lived there, most of them unemployed, most of them on dirt roads, surrounded by the Daniel Boone National Forest. For twelve years, during the 1960s and 1970s, I walked to school on a footpath through the woods.

Like many ambitious country people, I couldn’t wait to leave. My interests—books, film, theater, and art—were unavailable in the hills. I knew such exotic fare existed in cities. During the next three decades, I lived in Manhattan, Boston, Los Angeles, Albuquerque, and Iowa City. In my supremely naïve country mind, I assumed that cities would be just like home, except with taller buildings and more people. But I didn’t fit into urban life any better than I had at home. Leaving the hills was like being an immigrant within my own country; it required new ways of thinking and talking. I soon learned to walk differently, taking on the rapid scurry necessary to sidewalks. Twice I moved back to Kentucky, but that was no solution. The act of departure had rendered me even less suited for life back home.

A native of a city can stroll the old neighborhood and see the evidence of rapid change. The corner drugstore is now a Korean market, the old barbershop is a cell-phone store, and the alley where you smoked your first cigarette is part of a massively renovated condominium. It doesn’t work that way in the country. Our changes are less dramatic, although equally meaningful. There’s less focus on the new and more on what has vanished—where the old Johnson place used to be, or the old railroad bed, or the empty mine. The most visible change is the proliferation of chain stores, which have choked out local businesses. They are as bad as kudzu and sweet gum.

I now live on fourteen acres in Lafayette County, Mississippi, near Oxford. I’m a gun owner, drive a pickup, and fish from a johnboat. I also recycle, believe in women’s reproductive rights, and own a Prius as a second car. Politically, I don’t fit in anywhere, either.

Last fall, Kim Davis, the elected court clerk of Rowan County, Kentucky, refused to issue marriage licenses to gay couples. That’s my home county. I knew Davis, her cousins, and one of her husbands. My mother was friendly with her mother. Davis soon became a darling of the far right, while her stance led to a six-day incarceration. Mike Huckabee and Ted Cruz, both Republican presidential contenders, visited her at the county jail. Local people held mixed opinions, but many resented her behavior for its negative impact on business, tourism, and university recruitment. Most were shocked to learn that her salary was nearly $80,000—at a time when the average in Rowan County was $33,000. For that kind of money, people said, she ought to do her job!

After Davis became a short-lived celebrity, I began joking that I was the only person in the United States who had moved to Mississippi for its progressive politics. That humor ended abruptly in April, when Governor Phil Bryant approved House Bill 1523. Under the preposterous auspices of protecting religious liberty, the new law attempted to create a system of apartheid, allowing businesses and government agencies to deny services to gay people. The next week, the governor signed another controversial law, this one permitting concealed guns in churches. The local newspaper ran a photo of him at his desk with a holstered Glock resting on a Bible.

In June, a U.S. district court struck down H.B. 1523. Judge Carlton Reeves argued that it “would demean LGBT citizens, remove their existing legal protections, and more broadly deprive them of their right to equal treatment.” Under current law, Mississippians can’t legally discriminate against gay people. But they can still go to church armed.

Meanwhile, in Kentucky, Republican politicians have been attacking the education system. (Coincidentally, statistics suggest that less educated white men are more likely to vote for Republican candidates.) After taking office in December 2015, Governor Matt Bevin overhauled the University of Louisville’s board of trustees and proposed cutting $40 million in state funds to the University of Kentucky. My alma mater, Morehead State, eliminated sixty-four positions and forced all faculty and staff to take an unpaid furlough.

The governor’s crusade against public education is only beginning. In the future, Bevin says, funding for higher education will be based on performance, although it is unclear how that will be measured. In January, he did issue one clarification: “There will be more incentives to electrical engineers than French-literature majors. There just will.” The problem, in Bevin’s view, is that public schools are not supplying “things people want.” The people he’s talking about are employers, not students. The governor hopes to transform his state’s fine public universities into vocational schools.

The great irony is that Bevin attended a private college, and graduated with a liberal-arts degree. Instead of putting it to use, he inherited a family business founded in 1832. Perhaps the nation’s oldest manufacturer of bells needs more electrical engineers—what do I know? I have a liberal-arts degree from Morehead State, the only four-year school in the Kentucky hills, and it has served me well. After graduating, I worked at more than fifty part-time jobs, most of them involving manual labor. In the end, though, I became a writer and college professor. I went from painting curbs on one campus to teaching on another.

Many working-class people in rural areas do not finish college. The reasons for this are complicated. Morehead State was less than twelve miles from where I grew up, but most colleges are farther away than country people want to go. In addition, higher education is regarded with suspicion, a potential means to “get above your raisings”—that is, to forget who you are, where you came from, and who your people are. What begins as cultural pride evolves into an actual fear of education. A college graduate is widely perceived as the kind of person who takes advantage of others, who believes that visible signs of wealth are important, who might turn snobby with a little money.

In 1974, the Charlie Daniels Band released “Long Haired Country Boy,” a song that quickly became an anthem for my friends and me. With a simple eloquence, the third stanza encapsulates the rural view of social class:

A poor girl wants to marry

A rich girl wants to flirt.

A rich man goes to college

But a poor man goes to work.

There is a pragmatic element here: college is too expensive for most lower-class families, no matter where they live. The flip side is that people in the rural South who do go to college are more likely to keep it to themselves. It’s a source of personal pride, not status.

The biggest change in rural life is the same as in cities: the advent of technology. We have computers and smartphones! We watch the same terrible TV shows! For fifty years, my parents sat in front of the television and bickered over the names of the actors. My father always won, simply by wearing my mother down. One year, I gave her an iPad, which she kept on the couch beside her. My mother soon began winning these marital movie battles, irritating my father to no end.

In a big-city restaurant, you will see at least a third of the diners fiddling with their phones. The same is now true of a rural bonfire. In short, country people are far more connected to the cities—and to the global community—than was previously possible. Some of us march in gay-pride parades and believe in equal pay for women. Some of us are even vegetarian, no easy task in the land of barbecue. It’s true that we tend to own more guns than city people, but we don’t shoot one another as often.

This larger connection to the world is not a completely new development. The cultural isolation of the hills began to erode in the 1990s, when cable TV arrived. During those years, I was surprised to see country boys driving lowriders with their hats reversed, listening to Tupac. Their circumstances could not have been more different from his—but the underlying sense of rage and injustice was universal. (At age nineteen, I embraced punk for similar reasons, and never forgot the Clash’s response to economic inequality: “Career opportunities are the ones that never knock.”) Tattoos are also as prevalent in the hills today as they are everywhere else. If I were in my early twenties now, my torso would undoubtedly resemble a comic book.

In certain ways, greater access to mass media has been a drawback. In particular, it has made the young more aware of what their environment lacks. Bored people with few available jobs seek an escape—hence the spike in meth and oxycodone use in many rural areas. Drug problems in the region are not due to a genetic predisposition or a byproduct of Appalachian culture. Anyone who believes that is a damn fool who has not spent enough time in the hills. No, the rise of substance abuse stems from the same dilemma I faced as a youth: nothing to do and nowhere to do it. But today’s young people have it worse, and the popular drugs are far more dangerous.

When I was a child, the federal government “discovered” Appalachia and declared a war on poverty—Lyndon Johnson launched the entire program in Inez, Kentucky. The American solution to any problem is to throw money at it, and in 1968, television was supposed to help the schoolkids. Kentucky Educational Television had just begun broadcasting, and a TV set was dutifully placed in every classroom of my elementary school. These were the biggest televisions that any of us had ever seen, mounted on tall steel carts with heavy casters. The principal set aside time for KET, and my entire fifth-grade class was joyful about this development. At the appointed hour, we positioned our desks so that everyone could see the screen. The teacher closed the blinds and turned off the overhead lights. She flicked on the TV. We sat there and waited—and waited. Unfortunately, there was no reception. The federal administrators had overlooked a fundamental fact of geography: most Appalachian schools were built in a hollow between two heavily wooded hills. The expensive television gathered dust in a corner.

Another federal initiative of the era was the VISTA program, which mostly brought in workers from Northern cities. Viewing the hills through urban eyes, they decided that what the local children needed was a youth center. Admittedly, we were a ragtag bunch. We rode bicycles through the woods and wore threadbare clothes that would protect us from low limbs and briars. What the idealistic VISTA workers didn’t understand was that we had no interest in being indoors—we had the entire woods to play in.

Nonetheless, construction materials arrived, and VISTA began prepping the site for the youth center. Before work could begin, the concrete blocks and lumber mysteriously disappeared. In a circuitous and unintended fashion, VISTA had provided the community with what it needed: building materials to repair people’s houses.

In my part of the country, the celebrated war on poverty was little more than a skirmish. It failed to address the primary issues: geographic isolation, a diminished belief in education, and a lack of employment. (Career opportunities never knocked.) The Head Start program has been a success, and there is a welcome increase in social services. Otherwise, the same patterns keep playing out. In recent years, a nonprofit called Gateway Community Action ran a program in the hills to weatherize houses by installing insulation, replacing old furnaces, and patching roofs. One of my childhood bicycle buddies, Faron Henderson, worked on houses for the program. The pay was eleven dollars an hour, not bad for the area, and Gateway provided him with health insurance, a first for Faron. But the program was also top-heavy with office personnel. As Faron put it, “They got paid good money to give money away.”

Pride is a major factor in the lives of all working-class people, regardless of ethnicity. We are proud of diligence, of ownership, of paying our bills, of making ends meet. Proud of not cheating or lying to get ahead. Proud of not owing anyone a damn thing. Other than a house, I have never made a purchase unless I could pay cash, which I’ve been told is a foolish habit, contrary to the American way. Such pride can be a double-edged sword, of course, making it hard to accept assistance. In my twenties, I resisted generous offers that would have improved basic elements of my life because I couldn’t stand the idea of being indebted.

It was easier for me: I was single, with no kids, and had moved away seeking work. For local people with families, accepting help was often a necessity—and to this day, many people throughout Appalachia receive federal assistance in the form of unemployment, TANF, Social Security, and Medicaid. In a culture built so solidly on self-reliance, this often produces shame. I’ve seen mothers wait for an empty grocery line in order to hide their use of food stamps. The loss of pride is intolerable, as is the utter lack of a job, any job. And yet that pride can cut both ways.

When I was a child, my home county had a single movie theater. It was woefully outmoded, with clanking projectors, seats that lacked cushions, and an audio system full of static. When I was ten, a new theater with a massive screen was built on Main Street. The floors were carpeted and the wallpaper had strips of decorative flocking. Scooting the soles of my shoes on the carpet and touching the wall produced a small electrical charge. Our new theater was so lavish that the walls gave off sparks!

Years later, the theater began offering a price break for Morehead State students on certain nights. It was smart marketing. There were several thousand students with little to do in a small town. I was gone by this time, but visited often, and always saw Faron. Strong, hardworking, and smart, he had taken many tough jobs: running power lines through the hills, overseeing freight cars at a switchyard, and construction work. For more than a decade, he drove three hours a day to Lexington and back for a job as a plumber. Or, as he put it, “Ten years of making shit run downhill.”

During one of my visits, we decided to cruise Main Street in his new truck. We passed the theater and Faron reminded me that his dad had helped build it—but now Faron refused to step inside. I asked him why. He said it wasn’t right that rich college kids paid a dollar less for a movie while a poor workingman had to pay full price. I told him I’d pay his way, and he shook his head. I said I’d give him a dollar against his ticket, and he said, “That’s not it, Chris. You don’t get it, do you?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Those college kids sit in air-conditioned classrooms and live in air-conditioned dorms. I work outside all day long. Nothing I’d like better than sitting inside and watching a movie. But I’m not paying a dollar more than another man.”

“Maybe you should go into the air-conditioning business.”

We laughed for the full two minutes it took to cruise Main Street both ways. Faron had a point, but he was blaming the wrong people. The college students weren’t interfering with his entertainment possibilities. It was a business decision made by an out-of-state corporation.

In today’s world, the white working class is still blaming the wrong people. There is a painful irony here. We live in a land of white privilege: a concept it took me many years to understand. After all, everyone in Haldeman was poor and white. The only privileged people I knew were members of wealthy families who lived in nearby Morehead. As a young man, I left on foot, hitchhiking north, then west. For me, privilege meant owning an automobile.

In cities, I lived in poor neighborhoods, where the police rarely treated me as a suspect, and more often as a potential witness or victim. If I was the only white person working on a labor crew, the customers would automatically talk to me. In public situations, there was a subtle deference that came my way: quicker service at a hot-dog stand, a touch more respect in a bowling alley, less scrutiny in a mall. This, I came to understand, was the core of white privilege, a way of benefiting from my race without knowing it.

If you are white, there is some part of you that internalizes this invisible social lesson. At the same time, working-class white people from my part of the country don’t feel privileged. There are few advantages to growing up on the side of a hill, or out on a ridge, or deep in a hollow. We are a marginalized population. Mainstream society acknowledges our presence primarily as the butt of jokes, satire, and stereotype. Pouring scorn on the white underclass is always a safe tactic, because we are too reflexively independent to organize and have no real leaders to represent our interests. “Hillbilly,” “redneck,” and “white trash” are epithets as cruel as any racial slur, but they are acceptable in society—acceptable not only in popular media but in left-leaning periodicals, whose editors really should know better.

This mixture of invisible privilege, highly visible ridicule, and pride leads to resentment. White-working-class rage played a role in both the Tea Party and the Sanders revolutions. This anger is stoked in every region of the country by the steady incursion of right-wing thought, a form of cultural conversion. Wielding a populist Christian rhetoric, the G.O.P. attacks unions, education, immigrants, and minorities. Their latest theater of operations is the public restroom, where they want to restore the segregation that was typical of public water fountains until the late 1960s, with transgender people in the role once assigned to black Americans.

The rise of the Republican right amounts to the other great change in rural life, on a par with cell phones and cable TV. When Faron and I were kids, our families voted Democrat, as did most of the people in our community. The unions, traditionally Democratic strongholds, were still forces to reckon with—especially the United Mine Workers. The culture, too, was in a rebellious phase. We grew our hair long and listened to Lynyrd Skynyrd, Charlie Daniels, the Allman Brothers, and the outlaw movement from Nashville, led by Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson. Those guys wore the same clothes we did. They smoked weed, shunned the mainstream, and were decidedly progressive. Today’s country stars drape themselves in the flag and wear tight jeans, boots, and the obligatory Western hats. Their music is as homogeneous and boring as their onstage personas and carefully cultivated twang. The schematic lyrics remind me of a politician’s talking points: dog, beer, truck. I quit listening to AM radio’s contemporary country long ago, and Faron switched to an oldies station.

These days, he runs a car-detailing business out of his garage. He’s unsure who he’ll be voting for. He dislikes both candidates equally. The Republican Party succeeded in tarnishing Hillary Clinton’s image while failing to provide a viable nominee of its own. The Democrats failed as well, continuing their decades-old abandonment of the white rural voting bloc—those with college degrees and those without. Leaderless and adrift, these voters are ripe for someone who sounds confident, who is as angry as they are, and who is certain he can single-handedly fix their problems. I’m talking about a rabble-rousing strongman in the vein of Mussolini, a man proud of his multiple bankruptcies, a braggart who is blind to his own bigotry.

Donald Trump’s appeal is the illusion of strength. He doesn’t back down. He calls them as he sees them. He’s brash and outspoken. He never apologizes. He meets opposition with a stronger attack. He’s not on the payroll of the political system, not a stooge for the bosses. He pays his own way. His supporters share these values, which form a cultural bedrock of working-class life, and in many ways, I share them as well.

But Trump does not speak for any particular rural demographic, and he is not giving voice to the grievances of the white underclass. It is a peculiarity of branding that the man most famous for firing employees on camera has managed to package himself as a champion of the workingman. But his real achievement is tapping into the frustration of people who feel ignored. His popularity in the hills and in the most devastated parts of the rust belt is simple—no one else has paid attention to these voters. The only good thing to come out of Trump’s candidacy may be an increased national awareness of this population. They are as American as the people in California and, yes, Connecticut. And their votes are clearly up for grabs.

I am tired of Democrats blaming their uncertain prospects on the rural South. It simply isn’t true. Trump may enjoy strong support in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee—but his position on free trade resonates in every single state that has lost jobs in farming and manufacturing. His most commanding lead is among white voters who didn’t go to college. Education, I would argue, is the crucial factor, not social class or geographic region. Race and gender are next.

My eighty-one-year-old mother has voted in every presidential contest since 1952. I visited her recently and mentioned the election. She said she’d lately been thinking about her grandfather, a yellow-dog Democrat and career bartender.

“He’d have rolled over in his grave if he’d lived to see a black man elected president,” she told me. “But you know what’d be worse for him?”

“No.”

“A woman president. He’d just shake his head over that.”

“Is it worse?”

“Not to me,” she said. “I’m glad I’m alive to see it. I used to think landing on the moon was a big deal. This is bigger.”

I thought about her words for a long time. Much of Trump’s popularity is clearly based on the backlash against Barack Obama. His other great appeal is sexist. His opponent is a woman. Which group in this country has the lowest regard for women? It’s not poor Southern whites and blacks, many of whom rely on women to hold families together. It’s not people in the rust belt, where women have long toiled in factories alongside men, or in Montana, which in 1916 elected the first woman to Congress. The demographic I’m talking about is white conservative men who didn’t go to college and never miss church on Sundays. They are not limited to a particular region or class. They are everywhere. For a long time, I thought Trump was destroying the G.O.P. Now I think he’s exposing it.

Anyone who has lived in the country understands the brutality of nature. Animals kill to survive and fight to the death. A cornered animal experiences a surge of sudden ferocity. During its final minutes, when the animal knows it’s going to die, it will emit a specific sound, a warning to others of the same species. That sound is known as a death cry. I believe we are hearing the death cry of the G.O.P. in its current incarnation: racist obstructionists who welcomed the squalid alt-right into their midst and failed to produce a credible nominee for president. They had their chance, and blew it. They dismantled unions, systematically attacked education, and ignored the separation of church and state. They gave corporations the same rights as people while trampling the rights of actual human beings. Unlike other animals, which know the death cry as a warning, too many Americans are responding with a sense of outraged empowerment.

Will Trump make America great again? The question is absurd. The real question is this: when was the country great, and for whom? In the not-so-distant past, it was certainly better for union members who could earn a living, for educators whose jobs were not tied to test scores, for anyone who worked in manufacturing. The country is better now for people of color, for gays and lesbians, for women, and for the disabled. This progress has been grotesquely misinterpreted to mean that the country is worse for white people. Such thinking is false logic. One does not rule out the other. Straight white men, especially those who have inherited family fortunes, are doing just fine in America. The problem is that some of them are trying to ruin it for the rest of us.