Discussed in this essay:

Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs, by Douglas Smith. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 848 pages. $35.

The Romanovs: 1613–1918, by Simon Sebag Montefiore. Knopf. 784 pages. $35.

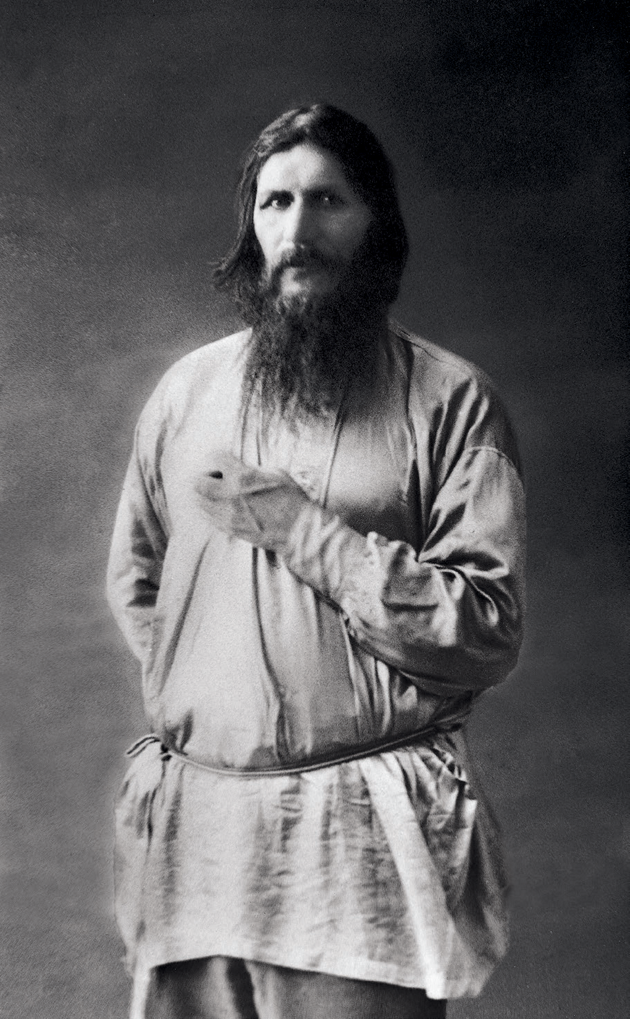

He is the mad monk, the holy fool, the man whose mystical powers enthralled the tsarina and cured the tsarevitch. It is said that he was a hypnotist, a rapist, a cultist, a charlatan, a seer. Allegedly, he was immune to poison; when his murderers tried to drown him, his body floated to the surface. In the century since his death, Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin, the Siberian priest whose relationship with Nicholas II and Alexandra, the last tsar and tsarina of Russia, helped bring down the entire Romanov dynasty, has been the subject of countless myths — so much so that it has become nearly impossible to disentangle the man from the legend.

The myths were no less pervasive when he was alive. During the final years of the Russian Empire, the holy man was at the height of his power and influence. Alexandra was convinced that he could cure her son’s hemophilia and gave him unprecedented access to the royal family. Nicholas saw in Rasputin an embodiment of the peasantry, the real Russia, in whom he had so much faith. (Right up to the moment of his abdication, he expected the people’s love and adoration to save him.)

But Nicholas’s subjects hated Rasputin and resented his influence over the imperial family. The press published extraordinary accounts of his sexual escapades and his supposed corruption, of his political machinations and his sway over the tsar; and the public — the peasants, the workers, the aristocrats, and the intellectuals alike — lapped them up. In a diary entry from 1916, Lev Tikhomirov, a Russian intellectual and recovering revolutionary, grappled with the problem of Rasputin:

People say the Emperor has been warned to his face that Rasputin is destroying the dynasty. He replies: “Oh, that’s silly nonsense; his importance is greatly exaggerated.” An utterly incomprehensible point of view. For this is in fact where the destruction comes from, the wild exaggerations. What really matters is not what sort of influence Grishka has on the Emperor, but what sort of influence people think he has. This is precisely what is undermining the authority of the Tsar and the Dynasty.

Douglas Smith, the author of the definitive new biography Rasputin, takes this comment to heart. Writing that “there is no Rasputin without the stories about Rasputin,” he devotes more than 700 pages to unraveling each yarn. He looks at letters and memoirs, including the many fake memoirs, in addition to short stories and plays that were written about Rasputin and his entourage. He consults the voluminous archives of the Okhrana, the tsar’s secret police, which was carefully watching Rasputin, as well as his family, associates, and friends. He has used new documents and reread familiar ones, comparing sources in order to establish what actually happened during Rasputin’s lifetime.

The outlines of his early years are mostly agreed on. He was born in 1869 in the western Siberian village of Pokrovskoye, the son of relatively well-to-do peasants. He was the fifth of nine children, and never attended school. He married at eighteen, had seven children of his own, then drifted away to a monastery, where he became a fanatical believer and a wandering preacher, joining a long Russian tradition, and soon developed a reputation for spiritual healing. He traveled, rendering his services from Kiev to Kazan, and around 1905 wound up in St. Petersburg, at a time when the monarchy and the empire were experiencing a series of crises: a failed war with Japan, a popular revolution, economic turmoil.

Friends recommended him as a spiritual counselor to other friends, and eventually to the emperor. Nicholas recorded their first meeting in November of that year: “We made the acquaintance of a man of God — Grigory, from Tobolsk province.” The imperial couple had recently broken ties with another spiritual huckster, a Frenchman named Philippe. Rasputin took his place. Within months, he had become an intimate of the family. After Nicholas and Alexandra became convinced that he could help cure Alexei, their hemophiliac son and heir, he became impossible to remove. And the closer he grew to the family, the more outrageous the rumors about him became.

Smith concludes that some of the most damaging stories were accurate. During his time as a Romanov insider, Rasputin saw prostitutes, slept with some of the aristocratic ladies in the imperial court, and frequently got drunk. He also tried to guide some of the tsar’s personnel appointments, especially after the outbreak of the First World War; he opposed Russian involvement. In the spring of 1915, he held a long meeting with the minister of finance, whom he was hoping to have replaced with a candidate of his own preference.

But it also becomes clear that his political role was exaggerated by the climate of hysteria and suspicion. Early-twentieth-century St. Petersburg was a breeding ground for odd cults and mystical groups, theosophists and seers who claimed they could speak to the dead. After the Japanese debacle, the Russian elite was pessimistic about the future of the empire. Rapid modernization and industrialization had shaken the social structure entrenched over centuries, leaving both the peasantry and the new working class cut off from their religious and spiritual roots. As casualties mounted in the First World War and the economy suffered, many Russians began to believe that they were the victims of a secret conspiracy, as Smith explains:

Shadowy actors, hidden from view, were the ones truly in charge of the situation. Tyomnye sily, they were called, “Dark Forces.” They could be different things to different people — Jews, Germans, Freemasons, Alexandra, Rasputin and the court camarilla — but it was taken on faith that they were the true masters of Russia.

In this atmosphere, plenty of people in St. Petersburg had an interest in feeding the exaggerations about Rasputin. That becomes clear when Smith dissects one of the most scandalous tales: the incident at the Yar restaurant in Moscow. According to the rumors, Rasputin showed up at the restaurant with his friends late on the evening of March 26, 1915. He got drunk, danced, and lunged at the Gypsy girls who were there to provide entertainment. He bragged about his clout over the royal family and said obscene things about the empress. At one point, he took off his trousers and exposed himself, “as if to prove the source of his hold over the empress and society women.” What started as a rumor evolved into a series of newspaper stories before finally achieving the status of historical fact.

Robert Bruce Lockhart, a British diplomat and spy who wrote a memoir of the period, claimed to have seen the police arrive and drag Rasputin away. Except that he didn’t: Lockhart wasn’t in Moscow at the time, didn’t mention the incident in his diaries, and probably boasted about it later only to add to his own renown. Nor is there evidence that the Okhrana observed the scandalous events that evening, despite having multiple agents following Rasputin around the clock. Smith writes that these agents shadowed him across the city. They recorded each of his meetings, investigated his contacts, and telephoned his movements back to headquarters. They even noted that on March 27, he was led “in an intoxicated state” out of an apartment and driven around in a cab, possibly in order to get sober. On March 26, they did spot him entering the Yar restaurant, but noted no alcohol, Gypsy girls, or lewd boasting.

Two months later, however, Smith says that under orders from Vladimir Dzhunkovsky, an official in the interior ministry and a political enemy of Rasputin’s, the Okhrana concocted a new account. Their report included the names of people who had not been previously mentioned, as well as the sordid anecdotes that were doing the rounds in society. It alleged not just sexual misconduct and drunkenness but political intrigue: Rasputin was quoted offering to use his connections to “High Personages” to set up a corrupt deal.

Dzhunkovsky took a copy of the report to the tsar, adding that Rasputin was the “weapon of some secret society,” probably the Freemasons, “bent on the destruction of Russia.” Nicholas showed it to Alexandra, who called Dzhunkovsky a liar and a traitor. The tsar dismissed him. But the legend lived on, much longer than the monarch himself.

The holy man may have inspired an abundance of lurid and fantastical stories, but the Rasputin phenomenon was in fact the final act of a much longer story — that of the Romanov dynasty. As Simon Sebag Montefiore’s gossipy, intimate new history well demonstrates, the extreme emotions that gripped the Russian capital in the early twentieth century were nothing new. Montefiore, who has a knack for finding long-lost love letters and digging up forgotten figures, reminds his readers in lush, lucid prose that the Romanovs had been cultivating hysteria, anger, and conspiratorial thinking since their earliest days in power. The Romanovs is very much the history of a family — of relationships, rivalries, love affairs — and not a history of Russia. But as Montefiore reveals, even the smallest quirks and whims of such a powerful clan could have a devastating impact on the world at large.

He opens his account with an ironic parallel, observing that the Romanovs launched their reign in the same kind of chaos that would ultimately engulf them. The previous dynasty, the Rurikids — a family with Slavic and Scandinavian roots stretching back to the ninth century — ended when Tsar Feodor I died without an heir. Several pretenders, some backed by foreign states, tried to take power; the neighboring Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth invaded. The Russia of 1613, much like the Russia of 1917, had collapsed into civil war:

Famine and war had culled its population. . . . Swedish and Polish–Lithuanian armies were massing to advance into Russia; Cossack warlords ruled swathes of the south, harbouring pretenders to the throne; there was no money, the crown jewels had been looted; the Kremlin palaces were ruined.

Michael Romanov was only sixteen, a prisoner and a fugitive. His father, a relative of the last Rurikid tsar, had been captured and imprisoned by the Poles. But because he was too young, sickly, and uneducated to have any enemies, Michael was chosen by an assembly of boyars and Cossacks to rule this ravaged kingdom. He is said to have wept and wailed on being told of the arrangement. Still, he made his way to the Kremlin, the fortress-palace of Moscow, where he discovered burned-out buildings, rubble, and corpses.

Michael’s coronation didn’t end his travails, or those of his family. The woman he selected as his wife was poisoned. He eventually found another, who gave birth to ten children, many of whom died. However, the eldest child, Alexei, managed not only to outlive his father but to survive without much difficulty the inevitable infighting after Michael’s death. This relatively painless succession would prove unusual — in the centuries that followed, the Romanovs would regularly turn to regicide and parricide. Alexei’s two sons battled against each other; the victor became known as Peter the Great. Peter’s death in 1725 was followed by yet another battle, this time between his daughter, his widow, and his grandson, Peter III. The reign of Peter III was, in turn, brought to an abrupt end by his wife, an obscure German princess who organized a palace coup against him. (She would be remembered as Catherine the Great.) Each time power changed hands, careers rose and fell, rumor and gossip spiraled out of control, and emotions seized the court and the countryside.

At times, important noble families or influential priests would help shape the succession. But at no point during the dynasty’s existence did any of the Romanovs seriously entertain the idea that the public should play a role in decisions about who should rule and how. Nor was there any attempt to bring greater transparency to a monarchy that made its most important decisions in secret.

This was not because the Romanov tsars were unaware of the existence of democratic practices or constitutional monarchies in other countries. Peter the Great journeyed across Europe in the late 1690s, stopping in Amsterdam, Vienna, and London. He admired the technical accomplishments of the Europeans and became particularly enamored of Dutch and Italian shipbuilders, many of whom he hired and brought back to Russia. In Britain, he saw his first wheelbarrow, which impressed him so much that he held wheelbarrow races in the garden of the palatial house that he had rented, destroying the elegant topiary. Inside, his men wrecked the paintings, which they used for target practice, as well as the furniture, which they burned for firewood. The British, like other Europeans at the time, laughed off the antics of this obscure leader of an uncivilized land.

Although he visited a session of Parliament, even the limited British democracy of the era made no impression on Peter. None of his descendants showed much passion for it either. Catherine the Great’s interest in the Enlightenment led her to launch some educational projects and commission works of art, but not to share power. Alexander II, a relatively liberal nineteenth-century tsar, went so far as to liberate the serfs, the enslaved peasantry, but he did so unenthusiastically, declaring it was better “if this takes place from above than from below.” His son, Alexander III, abandoned his father’s reform plans altogether. He agreed with one of his courtiers that reform would lead to “the end of Russia” and that a parliament “based on foreign models” would lead to disaster: “Constitutions are weapons of all untruth and the source of all intrigue.” In the early twentieth century, Tsar Nicholas II also visited Britain and sat through a session of Parliament, but, as his ancestor had two centuries earlier, he drew no conclusions from the democratic process he observed.

Like his grandfather, however, Nicholas II was eventually forced into change. He allowed the creation of a parliament, the Duma, following the protests and strikes of 1905, and he appointed Russia’s first prime minister, Sergey Witte. He was not happy about it. He told a confidant that he would never forget the “evil days” when Witte tried to take him “on the wrong path” — that is, to create a constitution and a government — but he “hadn’t the strength to oppose him.” (Witte himself described the tsar as “this interlaced body of cowardice, blindness, craftiness and stupidity.”)

Only a few weeks after he was forced to share power with the commoners, Nicholas had his first encounter with Rasputin — that date in November 1905 noted so laconically in his diary — a man who, unlike Witte, treated the imperial family as the representatives of God on earth. As Montefiore points out, his sycophancy must have confirmed Nicholas and Alexandra’s “belief in the masses just as they feared they had lost them.”

In the end, Nicholas faced the same problem as all the other Romanovs: in the absence not just of democracy but of a constitutional system and rule of law, how could the tsar maintain power? As we learn from Montefiore’s colorful accounts of the succession battles, they often didn’t: tsars who were unable to keep control of their country — to say nothing of their courtiers, wives, and relatives — were often murdered. The more successful Romanovs often used patronage to secure support. As they expanded the borders of Russia to incorporate Siberia in the east and Poland in the west, they acquired land and estates, which could be bestowed on loyal retainers. Of course, this practice also made the succession battles even more bitter, since the friends of any potential tsar had a huge material stake in seeing that he or she actually took power.

Force and subterfuge were always part of the story, too. Peter the Great participated in the investigations and tortures carried out by Prince Romodanovsky, his chief of secret police. Catherine the Great used the Preobrazhensky Regiment, which Peter had created as her personal bodyguard, to carry out her coup against him. She showed her critics no mercy: when one young nobleman published a critique of her extravagance and despotism in 1790, she had him arrested and sentenced to death, though the punishment was later commuted to exile.

As revolutionary movements gained strength over the course of the nineteenth century, so did state-sponsored violence and the apparatus of invigilation. In 1881, Alexander II, the liberator of the serfs, founded the Okhrana, which he relied on to monitor protesters. The secret police were empowered further by his autocratic son, Alexander III, expanding from twelve people in 1866 to several thousand and creating exile colonies for criminals and political enemies alike. The first official use of exile as a punishment was in 1649, under the reign of Tsar Alexei. In 1825, Nicholas I sent the Decembrists, a group of high-ranking aristocrats, to Siberia for their feeble attempt at rebellion. (That punishment — the men were forced to walk the entire route, draped in chains — shocked Europe.) But by the end of the century there were thousands of people in exile, including many Bolshevik leaders, several of whom showed real talent for staging escapes.

From the beginning, the Romanovs also understood how to use pomp, circumstance, faith, and ideology to retain their dominance. To police his noblemen, Peter the Great imposed what Montefiore calls a “tyranny by feasting,” forcing his court to participate in elaborate dinners and games: “Between 80 and 300 guests, including a circus of dwarfs, giants, foreign jesters, Siberian Kalymks, black Nubians, obese freaks and louche girls, started carousing at noon and went on to the following dawn.” Montefiore explains their political function:

Here he was able to balance his henchmen, whether they were parvenus or Rurikid princes; he could play them off against each other to ensure they never plotted against him. Here he policed their corruption in his own rough way while he assigned duties, prizes and punishment. The horseplay was often more like hazing, humiliating his grandees, keeping them close under his paranoid eye, promoting his own power as they competed for favour and for proximity to the tsar. His games of inversion simply underlined his own supremacy. . . . At any moment Peter might switch from jollity to menace.

Peter also created spectacles for the general public. On his return from a military victory against the Turks in 1696, he staged a Roman triumph in Moscow, which included statues of Mars and Hercules, and himself dressed in a black German coat and breeches, a costume that would have mystified his subjects. Catherine the Great toured her empire on a trip organized by Grigory Potemkin, her lover and chief adviser. (The journey would provide the origins of the phrase “Potemkin village.”) Her entourage included fourteen carriages and 124 sleighs; when the ice melted on the Dnieper, the royal party moved on to “seven luxurious barges, each with its own orchestra, library and drawing room, painted in gold and scarlet, decorated in gold and silk, manned by 3,000 oarsmen, crew and guards and serviced by 80 boats.” It was designed to impress, and it did. One observer compared it to Cleopatra’s fleet.

These lavish displays expressed the power of the tsar, and by association the strength of the nation. As their grip on Russia began to loosen, the Romanovs kept up appearances — at a spectacular ball at the Winter Palace in 1903, guests came dressed in seventeenth-century costumes encrusted with jewels — and began deliberately fomenting national pride, xenophobia, and chauvinism. After the empire acquired Jewish citizens with the annexation of eastern Poland at the end of the eighteenth century, anti-Semitism became a tool of state policy. At first, Russia confined the Jews to the old Polish territories, the Pale of Settlement. Though they were allowed to move from the middle of the nineteenth century, they were never safe. Alexander III expelled the Jews from Moscow in 1891, and shuttered the main synagogue. Jewish women were allowed to remain in the city only if they were registered as prostitutes.

Nicholas II was a particularly enthusiastic anti-Semite, welcoming extreme ethnic nationalists to his palace at Tsarskoye Selo, outside St. Petersburg, with the words “With your help, I and the Russian people will succeed in defeating the enemies of Russia.” Jews symbolized everything he hated about the modern world. A newspaper, he once said, was a place where “some Jew or another sits . . . making it his business to stir up passions of people against each other.” Prime Minister Witte was a member of a “Jewish clique.” Alexandra felt the same way, speaking of “rotten vicious Jews” and disparaging people with Jewish-sounding names. During Nicholas’s reign, the Okhrana produced The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a notorious forgery that depicted a Jewish plot to govern the world, and had a hand in inspiring a particularly vicious wave of pogroms in 1905. Thousands of Jews died in these massacres, which were a precursor to the even worse pogroms during the civil war in 1918, as well as to the Holocaust several decades later.

In other words, Nicholas himself had helped to cultivate the fear of “shadowy actors, hidden from view.” He paid the price for it too, as well as for the fanaticism and suspicion instilled by the Romanovs over the centuries. In 1917, Rasputin was finally murdered by two noblemen who hoped their plan would save the monarchy. Though one of them, Prince Yusupov, later wrote a gruesome account of the killing, the holy man was in fact shot squarely between the eyes — possibly, intriguingly, with the help of a British spy. Nicholas and his family were killed less than two years later on the direct orders of Lenin. The assassins stripped their corpses, in preparation for cremation — they didn’t want their graves to become a place of pilgrimage — and discovered the jewels that had been sewn into the lining of their clothes. They also found four amulets, one around the neck of each of the imperial daughters, with a portrait of Rasputin and the words from one of his prayers.

Like the first Romanovs, the Bolsheviks took power amid chaos, famine, and destruction. And like the Romanovs, they continued to promote the hatred, fear, and envy that plague Russia to this day.