Discussed in this essay:

4 3 2 1, by Paul Auster. Henry Holt. 880 pages. $32.50.

Is there a more equivocal legacy for an American artist than being loved by the French? As reputations go, there’s something suspect about it. Maybe it means that such artists operate at a level of sophistication that eludes the booboisie. Or maybe it’s just that they represent some gimcrack Gallic notion of American authenticity. Edgar Allan Poe, Josephine Baker, Jerry Lewis, Woody Allen, Jim Harrison. It’s a peculiar subset, encompassing the sublime and the ridiculous, often both in the same figure.

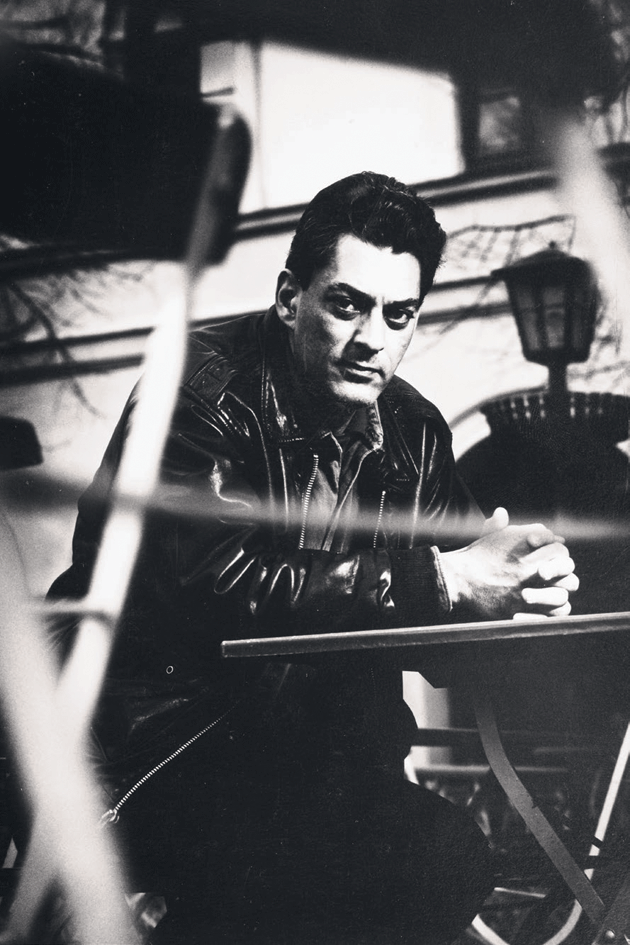

Paul Auster is a case in point. On the basis of the postmodern mysteries that make up The New York Trilogy, published in 1985 and 1986, Auster joined a short list of living writers whose place in the contemporary canon (and on the university syllabus) seems secure. The man himself is almost iconographic of serious literature — the black clothing, the sunken eyes and penetrating gaze, the smoker’s growl, the ready quotations from Beckett and Blanchot. (One of Auster’s college classmates recalled that he “would wander around in his long overcoat clutching French poems and translations of Tristan Tzara.” Auster was Auster before it was cool.) But what to make of him, really? Is he a major writer or does he just dress the part? Has his secret merely been to import the gimmicks and poses of the French avant-garde to the streets of New York, or has he absorbed and transformed those influences in such a way as to become a true American original? There’s something tauntingly indeterminate about Auster’s books. Cover one eye and what had seemed innovative suddenly looks like imitation, and vice versa.

Auster began his writing career as a poet, but the place to start if you want to try to figure out where you stand with him is The Invention of Solitude (1982), his first published work of prose. The book’s two parts reflect the double nature of Auster’s writing. The first assembles his memories of his estranged father, a real-estate speculator who had recently died of heart failure. The portrait of this miserly, emotionally stunted man forms an American tragedy in miniature, a succinct, devastating outline of repressed trauma and the soul-emptying wages of capitalism.

The second part is more conceptual. Auster confines himself to his tenth-story studio in downtown Manhattan to compose a series of third-person meditations on solitude — solitude as it relates to his upbringing, to his role as a new father, and to his vocation as a writer. Meshing stray recollections with excerpts from touchstone authors, the essay moves irresistibly toward the conclusion that it is impossible to fully understand a person’s life — and therefore impossible to write about it in any traditional way. “At his bravest moments,” Auster writes of the Auster who is writing, “he embraces meaninglessness as the first principle.”

The Invention of Solitude announces all the themes that have preoccupied Auster throughout his career: his issues with his father, his Jewish-American origins and suburban childhood, his deep-seated feelings of alienation and his compensatory enthusiasm for baseball and books, and his fascination with uncanny coincidences. But most important, it introduces the image of the solitary writer inside a locked room, ransacking his mind and his favorite texts to simulate the kind of plenitude he might evoke if he were out describing the world. In a locked room, the only observable action is the writer sitting at a desk, and in this stripping away of the elements that typically furnish a scene, the distance between thinking and composing contracts.

The result is the first instance of the archetypal Auster sentence, the sentence that watches itself being created: “He lays out a piece of blank paper on the table before him and writes these words with his pen. It was. It will never be again.” Later, in Travels in the Scriptorium (2007), we find: “Without another thought he picks up the pen with his right hand and opens the pad to the first page with his left.” Or again, from Man in the Dark (2008): “The night is still young, and as I lie here in bed looking up into the darkness, a darkness so black that the ceiling is invisible, I begin to remember the story I started last night.”

This claustrophobic self-awareness receives its purest expression in The New York Trilogy. The books belong to the lineage of metaphysical detective stories by nouveau roman authors such as Alain Robbe-Grillet and Michel Butor, who subverted the genre by devising unsolvable crimes, and by Patrick Modiano, who used it to investigate historical amnesia. But Auster’s open-ended detective tales are really extended metaphors about the agonies of writing. His gumshoes doggedly follow their marks, waiting for them to reveal their importance to the drama. (It never happens.) They stumble upon arcane patterns and allusive clues that they try to force into larger meanings. (That never happens, either.) Inevitably, they wind up alone in a room with a journal full of notes that add up to nothing — except, that is, the circular story you’ve just read.

Auster is sometimes celebrated as a chronicler of New York, but in the trilogy the city is flattened to the two dimensions of paper. Even the system of gridded streets is likened to the quadrille-ruled notebooks favored by Auster and his fictional stand-ins. Indeed, one of the most obnoxious things about Auster’s locked-room fables is that they fetishize writing paraphernalia, as though the art of writing were identical to the physical act of doing it (or pretending to do it). In book after book, stationery is endowed with ludicrous talismanic properties. The hero of Oracle Night (2003) effuses:

The Portuguese notebooks were especially attractive to me, and with their hard covers, quadrille lines, and stitched-in signatures of sturdy, unblottable paper, I knew I was going to buy one the moment I picked it up and held it in my hands.

The summa of this posturing may be The Story of My Typewriter (2002), a series of paintings of Auster’s Olympia portable typewriter (by Sam Messer) alongside a chin-stroking homage to the device.

It’s stuff like this — bullshit, in a word — that casts so much suspicion on Auster and his work. The self-mythologizing, portentous symbolism, and murmured cod philosophy conjure an ageless overcoat-wearing undergrad, a Peter Pan of pretentiousness. Yet Auster’s zealous productivity challenges this impression: for decades, he really has gone into small rooms and come out with intellectually searching manuscripts. He possesses an apparently inexhaustible need to immerse himself in the material of his youth. Much like Modiano, Auster is essentially writing the same book again and again, and these endless variations lend his writing its haunted intensity. The ghosts of earlier books are always knocking around inside the walls of the new ones, and the more he writes, the louder their banging becomes. The power of his best work is largely due to repetition and accumulation — to his faithful pursuit of the mission proposed in The Invention of Solitude, to explore the “infinite possibilities of a limited space.”

At nearly nine hundred pages, 4 3 2 1 tests this proposition at greater length than ever before. Auster’s new novel imagines four versions of the life of Archie Ferguson, a Jewish boy growing up after World War II in the working-class boroughs of New Jersey (his goyish surname is the result of an ancestor’s mix-up at Ellis Island), where his father, Stanley, runs an appliance and furniture store and his mother, Rose, works at a portrait-photography studio. After a prologue about their marriage and Archie’s birth, the novel splices its four parallel story lines, following its hero to early manhood.

The book uses the Catch — Willie Mays’s legendary over-the-shoulder grab of Vic Wertz’s fly ball in the 1954 World Series — to propel Ferguson’s lives along their forking paths. In part 1, Lew, one of Stanley’s brothers, makes a killing betting on Mays’s Giants, which tempts another brother to make his own fortune by robbing the furniture store’s warehouse. Stanley forfeits the insurance money by refusing to prosecute his brother, which consigns him and Rose to a lifetime of difficult but self-respecting economic struggle and instills in Ferguson a pragmatic professional ambition that complements his natural artistic bent.

In parts 2 and 3, Lew bets against the Giants, falls into debt with gangsters, and puts in motion a plan to burn down the family store for the insurance. In part 2, Stanley goes along with the arson but becomes so ashamed of his collusion that he shutters the business. In part 3, he tries to stop the scheme and is killed in the fire, and Ferguson and his mother move to Manhattan, where she remarries and he grows up to be more solitary, vulnerable, and prone to anguish than his other incarnations.

Part 4 skirts the problems with Ferguson’s feckless uncles altogether. Stanley buys out their shares of the store, which allows him to grow rich, join a country club, and move his family to the swank outer suburbs. His rise in station, however, makes him vain and tightfisted, planting the seeds for a divorce from Rose and a falling-out with his disaffected son. This Ferguson is marked by a defiant rejection of his father’s materialism.

It’s hard not to notice that the Stanley of part 4 has a lot in common with the father depicted in Auster’s memoirs. The new novel may sound like a high-concept, formally pyrotechnic book, yet Auster’s approach to his material is hardly out of the ordinary — he draws on his own life experience, tweaking details and outcomes as it suits him. The pleasures 4 3 2 1 offers are fairly traditional as well. As a time capsule of New York and New Jersey in the Fifties and Sixties, it is consistently engrossing. The backdrops of Ferguson’s early lives are filled with sports events and news items, TV shows and pinup girls and product logos. (In one thread, his first stirrings of sexuality are kindled by the drawing of the topless goddess Psyche on the White Rock seltzer bottles.) There are fond evocations of the Thalia, the beloved Upper West Side art house, and of the Horn and Hardart automats; of New Jersey’s poky Erie Lackawanna commuter train, with its “antiquated wicker seating,” and of shabby-chic Gauloise cigarettes, “overstrong, brown-tobacco fat boys in the pale blue packages with no cellophane around them.” Ferguson’s branching lives take him to Columbia University, Princeton, and Paris, and these settings, too, are documented to an encyclopedic degree. The bygone hazing ritual for incoming Columbia freshmen? Wearing powder-blue beanies during Orientation Week. The cost of airmailing a package from France to London in 1966? More than ninety francs, or around twenty dollars.

Auster’s late writing has shown something of a mania for inventories — his recent non-fiction works Winter Journal (2012) and Report from the Interior (2013) are free-associative catalogues of bodily sensations and mental images, respectively — and in 4 3 2 1 at times this tendency metastasizes into unwieldy historical checklists. (“The wall going up in Berlin, Ernest Hemingway blasting a bullet through his skull in the mountains of Idaho, mobs of white racists attacking the Freedom Riders as they traveled on their buses through the South.”) But more often the surplus description is born of generosity and exuberance. Auster has radically recast his prose, stretching the clipped, oracular style of his early books into unbuttoned run-on sentences like this one, about the weekend trips Ferguson number 4 makes with his stepsister to see the city’s museums:

The most memorable experience they shared together didn’t happen in a museum but in the more confined space of a gallery, the Pierre Matisse Gallery in the Fuller Building on East Fifty-seventh Street, where they saw an exhibition of recent sculptures, paintings, and drawings by Alberto Giacometti, and so pulled in were they by those mysterious, tactile, lonely works that they stayed for two hours, and when the rooms began to empty out, Pierre Matisse himself (Henri Matisse’s son!) noticed the two young people in his gallery and walked over to them, all smiles and good humor, happy to see that two new converts had been made that afternoon, and much to Ferguson’s surprise, he stood there and talked to them for the next fifteen minutes, telling them stories about Giacometti and his studio in Paris, about his own transplantation to America in 1924 and the founding of his gallery in 1931, about the tough years of the war when so many European artists were destitute, great artists like Miró and so many others, and how they wouldn’t have survived without help from their friends in America, and then, on an impulse, Pierre Matisse led them to a back room of the gallery, an office with desks and typewriters and bookcases, and one by one he took down from the shelves of those bookcases a dozen or so catalogues from past exhibitions by Giacometti, Miró, Chagall, Balthus, and Dubuffet and handed them to the two astonished teenagers, saying, You two children are the future, and maybe these will help with your education.

If Auster finds freedom in verbal profusion, he also finds it in conceptual restraint. It’s impressive how rarely he indulges in his usual brand of gimmickry, given that 4 3 2 1’s premise would seem worrisomely ripe for it. Perhaps he’s realized that the mainstream by now has co-opted most of the novelties of postmodernism. The idea that time can be cleaved in two is the stuff of romantic comedies like Sliding Doors. A character who continuously repeats his existence gives the impetus to Kate Atkinson’s thrilling (if incoherent) page-turner Life After Life. Ian McEwan and Haruki Murakami have forged book-club-friendly careers by playing cute games with narrative artifice.

In 4 3 2 1, Auster goes easy on the metaphysics. The resonances between his four Fergusons rarely feel overdetermined; they are glancing, circumstantial. To be sure, there are some gently ironic instances when the Fergusons muse about the role of chance or the variable nature of identity — “One of the odd things about being himself, Ferguson had discovered, was that there seemed to be several of him.” But such thoughts are natural to an intellectually rambunctious teenager, and Auster lays no more emphasis on them than he does on Ferguson’s flights of fancy about baseball, classical music, and sex.

This marks a significant change from The New York Trilogy, in which the connections are forged by cryptic coincidences. Volume 1, for instance, introduces a mysterious character with the initials H.D.; in volume 2, a detective comes upon a copy of Walden published by a company that shares the name of the man he is investigating; in volume 3, the narrator mentions a friend named Dennis Walden. You can parse these clues as much as you like, but because they don’t correspond to anything except other inscrutable symbols, the only meaning they enforce is their fundamental non-meaning. The point is to screw with you. “Nothing was real,” Auster warns, “except chance.”

Here’s how Thoreau appears in 4 3 2 1, from the point of view of Ferguson number 4, an aspiring novelist:

the thrill of reading such prose was never knowing how far Thoreau would leap from one sentence to the next — sometimes it was only a matter of inches, sometimes of several feet or yards, sometimes of whole country miles — and the destabilizing effect of those irregular distances taught Ferguson how to think about his own efforts in a new way, for what Thoreau did was to combine two opposing and mutually exclusive impulses in every paragraph he wrote, what Ferguson began to call the impulse to control and the impulse to take risks. That was the secret, he felt. All control would lead to an airless, suffocating result. All risk would lead to chaos and incomprehensibility. But put the two together, and maybe you’d be on to something.

Auster’s tilt away from the stifling control of locked-room mysteries toward the hail-mary risks of interwoven shaggy-dog coming-of-age stories is rejuvenating. He returns to many of his old hobbyhorses in 4 3 2 1, but here they are restored from the level of abstract metaphor to their rightful place in the real world. He plays around with pen names, not because he has a message to convey about the instability of labels and signifiers but because Ferguson is embarrassed to go by the comic-book name of Archie. (He chooses A. I. Ferguson in one version and Isaac, his middle name, in another.) Puns are plentiful, but they’re jokes Ferguson tells when he’s goofing around with friends, not indicators of recondite linguistic connections. And notebooks, rather than being some kind of sacred regalia, are just notebooks.

There’s even a clever adaptation of Auster’s recurring locked room. While at Columbia, Ferguson number 1 is trapped in his dormitory’s elevator during a thirteen-hour citywide power outage. It’s a revealing scene, in which Ferguson takes stock of his life, the Vietnam War, and his ambitions as a student journalist — all while trying not to piss himself. It also produces an eerie feeling of disassociation:

So dark in there, so disconnected from everything, so outside the world or what Ferguson had always imagined to be the world that it was slowly becoming possible to ask himself if he was still inside his own body.

Grounded in the real, his captivity regains its metaphoric possibilities.

The sensation of possibility is the most satisfying feature of 4 3 2 1. Of the many quotations that the four Fergusons single out from their extensive reading, one from John Cage’s Silence captures the novel best: “The world is teeming: anything can happen.” Because Auster takes each of Ferguson’s lives seriously as a vessel for experience and meaning, they build on one another rather than canceling one another out. The effect is almost cubist in its multidimensionality — that of a single, exceptionally variegated life displayed in the round.

Anything can happen, but what actually does? Though the book’s plots are by and large little more than scaffolding for Auster’s lavishly appointed memory theater, they’re still fairly lively. Rose is one of the few constants in Ferguson’s life, and the vicissitudes of her various existences are rich and intriguing — particularly in the story that sees her transform into a highly regarded photographer with Paris gallery shows. Ferguson’s foil is the passionate, politically active Amy Schneiderman, whose grandfather employed Rose at the photography studio. In one story the two fall in love in high school, and Ferguson’s maturation is directly tied to the ups and downs of their relationship; in another, because of Rose’s remarriage to Amy’s uncle, they become on-again, off-again kissing cousins; in a third, Rose’s divorce and remarriage makes them stepsiblings, devoted confidants, and museumgoing companions.

But the main developments have to do with becoming a writer: these are all portraits of the artist as a young man. The Ferguson of part 1 pursues journalism while translating French poetry on the side. The tortured, bisexual Ferguson of part 3 writes dark, confessional memoirs from a garret in Paris. The fellowship student at Princeton in part 4 is attracted to metafiction:

A book about a book, a book that one could read and also write in, a book that one could enter as if it were a three-dimensional physical space, a book that was the world and yet of the mind.

That nearly all these forms draw on aspects of Auster’s own career is not surprising, given the novel’s sources in the author’s life, but it does begin to hint at the book’s major limitation. For a while, Ferguson’s futures are unrestricted; then it quickly grows clear that he will be a writer, of one kind or another, and the task of the novel is to track the different routes to this destination.

These latter portions flag. This is perhaps symptomatic of all coming-of-age stories, which address the process of relinquishing cherished attachments; the arc they describe moves toward loss and isolation. But it’s especially true for an author as single-minded as Auster. As the Fergusons become increasingly preoccupied with the written word, the book’s side characters — Rose, Amy, a motley cast of friends and relatives — fade from importance. Politics comes to the fore of the narrative but doesn’t fill the space. Like Auster’s memoir Hand to Mouth (1997), 4 3 2 1 depicts the student demonstrations that beset Columbia in 1968. (Amy is a member of Students for a Democratic Society, a radical protest group, and takes part in the occupation of Low Library.) The account is thorough but bloodless because Ferguson remains a bystander. His friends are starting a revolution, he thinks, but he is “only watching it and writing about it.”

Ferguson, in all of his guises, has begun to look at the world as a writer does, from a cool, self-conscious distance. He’s observing what happens, but most of all he’s observing the way he thinks and writes about it. The blank sheet of paper has taken primacy over the landscape of experience. In each version, Ferguson manages to avoid being drafted into the war, even though such a turn would have taken the novel to wildly new terrain. It feels anticlimactic to see the boundaries of Auster’s imagination impose themselves quite so clearly. After all, he didn’t go to war; he became a scrappy, impoverished writer, and so, too, must Ferguson. Auster believes in the randomness of the universe, the contingent nature of fate, and the abundant possibilities of living — up to a point.

A familiar sense of inevitability gathers over the novel as it draws to a close. The paramount lesson of Auster’s books is that writers’ experiences stop at the end of youth, the moment they embrace their vocation and settle down to work. It’s at this point that this impressively ambitious novel, which begins with the broadest of vistas, retreats to the place in which so many of Auster’s books begin and end — a closed room with a man, alone, writing the words that you are reading.