Jed came downstairs. He worked mostly in the sleeping loft, writing serious journalism. His current project was about a friend’s imprisonment on charges related to terrorism. He said, “Laurie.”

“What?” She was sitting at the table, eating cereal and using the Tor browser on her encrypted laptop to read a friend’s personal newsletter. This week it was a funny-unfunny story about breastfeeding in a parking lot.

“We have to go.”

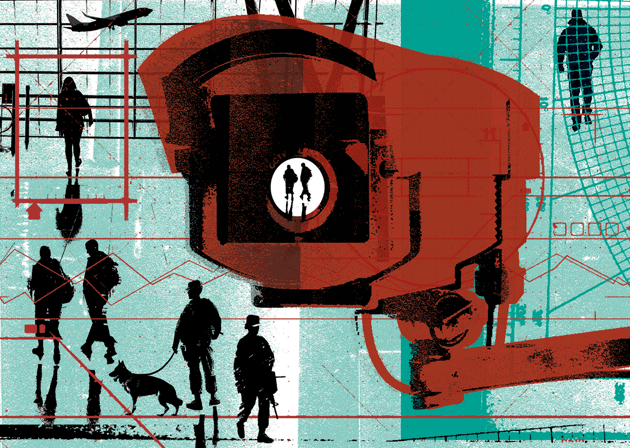

Illustration by Shonagh Rae

He had already counted their money in his head: $15,000 in cash, a premature inheritance from Laurie’s mother; $40 in fungible drugs; $200 in a PayPal account he couldn’t access. Getting locked out is what had told him it was time to go. They were renters in Detroit and owed $8,000 on the lease. They had $17,000 in credit card debt and $90,000 in student loans. None of it mattered but the cash.

They took a walk by the lake and talked about how to go.

Nonstop to London, obviously. Europe and Canada had great liberal reputations, but no borders. Any agent of any government could just come and get you.

It wasn’t hard: buy tickets with Laurie’s credit card, roll the money up very tight, put the money inside Laurie. Serious journalists live with their bags already packed.

Legally, they could have split the $15,000 between their wallets. But not in real life. The officers would ask about cash. Whether they lied or not, it would be taken away for safekeeping.

They drove to the airport and abandoned the car in the long-term lot. On the bus to the terminal they shared excited smiles like newlyweds on a honeymoon.

They checked their bags and got new boarding passes, because the airline was making everybody do it, for security reasons. The guards flanking the security chute had dogs. Jed and Laurie looked at the dogs and at each other. Some dogs were trained to smell money. Laurie imagined a body-cavity search. She looked at her phone and said, “Oh, my God! Mom thinks Dad’s having a stroke!”

Jed said, “Not again.” They rushed back to the check-in counter and told the ticket person that they had to cancel their vacation because of an emergency. He tore up their boarding passes and said they could come get their bags the next day.

After they were back on the highway, Jed said, “Now I guess they know we’re idiots. But we’re not dumb enough to want our bags back with their chips and software all over everything.”

“We could fly from some little tiny airport that doesn’t have dogs,” Laurie suggested.

“Nonstop to London? And besides, that’s where all the drugs go through. Civil aviation, home of drugs and dogs. They knew we were coming, that’s why they were checking bags!”

“We could upload our money to Bitcoin or something.”

“I know zero about how that stuff works, and I’m not about to start looking for information now. We need to turn the internet off and leave it off.”

“We need to wire money to ourselves using banks. I mean, like the old kind of banks that are institutions based in different countries, like —” She couldn’t think of an example. “We need the English version of a credit union.”

“One of us could go first and open an account.”

“No,” Laurie said. “We go together. They might stop one of us and not the other!”

“That would be bad,” Jed said, touching her hand.

“Don’t you know some NGO that could wire the money for us? Like Amnesty or Reporters Without Borders?”

“We would be so no-fly if we contacted them right now. Come on, we have cash. Let’s try again.”

It was hard to find a way to pay for new flights with no accounts working. But their neighborhood travel agent said, “The problem isn’t that we don’t take cash. It’s that you’re no-fly. Sorry!”

Jed felt called on to explain, so that the agent wouldn’t think they were terrorists. “It’s just that we had to ditch a flight with checked baggage when Laurie’s dad got sick,” he said. “With him sick, we ended up maxing out our credit cards. It’s a bureaucratic thing.”

“They screw up all the time and put people on the list who don’t belong there,” the travel agent said. “I’m putting in a review request. There.”

“Okay,” Jed said. “When do you think you’ll know whether we can go?”

“We could think about vacationing somewhere else,” Laurie said. “Like a train trip to the Rockies.”

“Wow, that was fast!” the travel agent said. “You’re approved!”

“Weird, but hey,” Jed said. Laurie hesitated. It was too easy. Why would federal agents invite you to come to an airport on a certain day at a certain time? Maybe not because they want you to fly away. The police don’t throw the nicest parties. But they get offended when you reject their invitations.

She counted out $1,800 and took the receipt for the e-tickets. The travel agent said, “Have a nice flight!”

Outside on the sidewalk, Laurie said to Jed, “She told Homeland Security we were flying to London with cash, and they offered to meet us at the airport. Did I understand that right?”

“Yes, ma’am. That’s what happened.”

“I am not going anywhere near that airport.”

“And what airport do you have in mind?”

“Is fifteen thousand enough for the barges?”

“No way,” Jed said. “I am not getting on a barge.”

They packed light and slept one night in the car. They left it in a vacant lot outside the old port of Biloxi, unlocked, with the keys in the ignition. They joined a crowd of people standing on a pier at midnight. They had $12,000 in cash.

According to the flyer, the price to ride on a barge being pushed out past the twenty-four-nautical-mile limit into international waters was an affordable $60 per person. For those who didn’t have a helicopter or a boat to meet them, the helicopter ride to the ship was $500. The ship to a beach in British territory was between $2,000 and $3,000, depending on which island they were anchoring at that day. Direct flights to London were available from each island.

Their “barge” proved to be a tugboat, and the fare was $300 per person, including babies. They were told the barges ran only on guaranteed windless days, and it was December — hurricane season.

Laurie and Jed boarded the crowded boat and went below. It was constructed like an iceberg, mostly underwater. They descended three slippery ladders, hitting people’s faces with their backpacks every time they turned. The hull was jam-packed with Americans from around the Mediterranean, the kind who turn brown in summer, fleeing to Europe, where they would still be considered white. “No way can they land a helicopter on this thing,” Jed said.

Some people paid with passports or drugs. One lady said she wouldn’t climb that ladder for a million dollars, so she got to stay on the tugboat for an extra two grand. It was a free market.

Up on the ship, thousands of people were already standing on the decks. It was more or less a tanker ballasted with rotting meat. Rusted cranes swayed overhead while sulfurous diesel fuel roiled from the smokestacks. Boarding completed, the contraption lurched eastward under murky skies. Laurie and Jed stood on a frail staircase near a huge, scary-looking windlass and held tight to a stiff cable attached to some kind of spar. There were sounds of metal slapping metal hard. People down on the deck were yelling, but Laurie and Jed couldn’t see why. It was too dark and windy to know anything.

The sun came up to starboard. Only one passenger out of the thousands, a fugitive drug dealer, had a phone with the kind of GPS that talked to satellites instead of Wi-Fi networks or cell towers or transponders on the ground. The passenger confirmed to everyone that the ship was headed north. A delegation went up to the bridge.

The captain said he was in big trouble with his higher-ups because the passengers hadn’t paid what they were capable of. His organization wanted him to dock in Pensacola and make the passengers shake down their families by phone before proceeding.

The drug dealer argued her case, pointing out that her organization was friends with the captain’s organization. The ship let down its only lifeboat, with about forty people standing in it, and turned southward again toward the Cayman Islands. The forty people were the passengers that the captain and crew had adjudged most likely to have relatives with money.

As Jed and Laurie watched the lifeboat wink away on the horizon, they felt a crippling fear that made them want to sit down and hold on to something solid. Holding each other didn’t really work because they couldn’t stop slipping and swaying. They stood on the steps and gripped the cable on the spar by the windlass.

Jed’s mistake had not really been his mistake — not personally, anyway. He would never have done anything that naïve. He had worked for the wrong magazine. That was all.

He had a colleague, a friend, who was a really great guy, but not cautious, and this guy had written a long article about Boko Haram. He went to northern Nigeria to interview girls who had married Boko Haram guys, and one girl, named Batula, made him extra sad.

She had been abducted with her mother when she was thirteen. Neither was very good-looking, and Batula didn’t know how to cook, so they had been assigned as wives to the same penniless, unpopular twenty-year-old. One day a French fighter jet zoomed in low over their camp. A tree was torn apart in an explosion and a piece of its trunk struck the girl, breaking her right arm near the top. Everyone, including the fighters, ran into the swamp, which was the core zone of a national park and had thus never been drained or logged and was still full of snakes, and there a mamba bit her mother, who died. The girl Batula kept running, holding tight to her loose arm. She hid in the swamp for weeks. The arm healed, but not straight or stable. She told Jed’s friend, through an interpreter, that she needed to get back to her village to see the bonebreaker. He would break and reset her arm. How she dreaded that moment.

Jed’s friend had used a journalistic forum — the pages of their struggling magazine — to raise money to get her to a hospital for a proper operation. The funds he raised, including $50 from Jed’s PayPal account, were clearly intended to benefit a terrorist’s immediate family. All the magazine’s assets were therefore forfeit under the law.

The publisher appealed the decision with help from the A.C.L.U. His magazine returned to business under its old name, but without its other assets, and was sold to a conglomerate. Nearly the entire staff was rehired, even Jed. But Jed’s friend stubbornly refused to provide Batula’s last name or the names of any sources who might have verified her story independently. He was sentenced to a year and a day for propagating fake news.

Everyone involved felt bitter, even Batula, who knew nothing about the ruined magazine or the prison sentence, or even the fund-raising campaign that had been supposed to help her. When she returned to her village, former neighbors who had moved into her home threatened to kill her in revenge for what Boko Haram had done. Her arm withered to baby-thickness and seemed frozen. She tied it to her side with a shawl. She wished it were gone.

Jed hadn’t been arrested or questioned or anything. But when he imagined his friend on his best behavior, bunking with strange convicts — assuming he was lucky enough to stay out of supermax or solitary, of which there was no guarantee, his being a terrorist supporter and all — it made him nervous.

What made him nervous, and who was at fault? Either it was something global that had spread from China to Russia to Turkey to Hungary to America, or it was something American that was latent all along. Or certain individuals were doing it, and they could be held accountable.

That had been Jed’s theory. Even a global sickness was made up of specific crimes committed by particular human beings, and if enough journalists told the story the right way, those individuals would feel ashamed and stop. That’s what he’d thought. Now he suspected himself of having been profoundly deluded. He’d been preaching a general strike, something like the one in Germany in 1933. It didn’t take down Hitler, but it ended the careers of the strikers — approximately a hundred textile workers in a single village. In the time it took them to demonstrate against Hitler, they could have walked to France.

The Coast Guard cutter was not supposed to be out that far, by law. It was sailing in clear violation of treaty as its loudspeakers demanded the smugglers’ surrender.

They were escorted to the port of Havana, where the passengers were given sandwiches and bottled water. Women with babies were allowed off the ship, along with a diabetic man in a coma and the drug dealer, whom American soldiers arrested.

Without warning, the ship was cast loose from the quay and continued to Miami. There the remainder disembarked to sit on hard chairs in a waiting area for cruise-ship passengers. Two thousand hungry people were crying, screaming, and yelling into their phones. Private security guards watched them all the time, even in the bathroom stalls, which lacked doors.

One by one they were interviewed. Two social workers alternated talking to the passengers. They were more talkative that way, and it was cheaper than law enforcement. Laurie and Jed said they had eighty dollars left and wanted to go home.

After four days, an old school bus carried them with some other similar passengers, young couples, to a prefab courthouse in a suburb that looked like a cornfield. They repeated the lie about the eighty dollars to the immigration judge. They still had four thousand. But there were no dogs at the courthouse, and no public defenders to advise them on whether being caught with cash was worse than advertising it. So they lied, and it worked.

They were set free, Laurie first.

She waited outside for Jed. She folded up her coat and put it on her backpack and sat on it in the shade of the trailer where prisoners were booked. The crabgrass had been mowed so short it was nothing but runners, like a white net to trap the soil. In the sunlight it was more blue than green, and the soil was hard gray clay. There were no bugs or weeds. It looked beautiful to her, like the earth from space.

“I’m so fucking hungry,” she said when Jed appeared.

They walked down the glaring asphalt road together. “We’ll just fly,” he said. “We can trade the cash for something valuable that doesn’t smell.”

“Everything smells.”

“Maybe diamonds?”

“Listen. Forget about the money. We’ll leave with what’s in our heads. We have education and skills. We even know English! That’s more than most people when they get to England.”

“I don’t know anything of value. I’m a complete loser. Didn’t you notice?”

“Get out of here. What are you talking about?”

“I’m a reporter with no information I can sell. I research powerless people who’ve been wronged, but nobody can sell that shit. You can barely give it away! What people want is leaks. And my research skills aren’t worth shit. I couldn’t even find out how to flee the fucking country like a rat. I should have been a conceptual artist. Maybe I am one.” He squeezed her hand affectionately, with a touch of contrition. She frowned.

Their feet started to blister from walking on the hard road without socks. At last, near the immense intersection that marked the middle of the suburb, they saw a lone bus idling. After an hour, the driver took his seat and the bus started to move. It stopped ten times a mile for thirty miles before reaching a light-rail station on the outskirts of Miami in the early evening.

Flying was easy this time. They were surprised how easy. They booked two seats from Miami to London, no luggage, paying in cash, and instead of saying, “I’m sorry, you’re no-fly,” the ticket agent said, “Goodbye, and good luck!”

“That was eerie,” Laurie commented. “It’s like he knows.”

Five hundred per person was not a lot for a weekend in London, so they carried five hundred each in their wallets, stashing the remaining fifteen hundred inside Laurie’s body. There were dogs all over, but they hadn’t showered since Baton Rouge. They didn’t smell like money anymore.

Nobody in the airport at that hour smelled like money. The four-in-the-morning flight to London was filled with people too poor for the barges. The media had failed, so they didn’t know how lucky they were. People with money schemed and suffered and failed to get out of the country. Emigrants who couldn’t have raised $10,000 to save their lives left on comfy planes, filled with hope. It was as if America were an addiction, and you had to reach rock bottom to start recovery.

At Heathrow, half the passengers halted before the immigration booths, looking around for the posters that explained how to apply for asylum. The others went through immigration as tourists.

For Jed and Laurie, it was a tough decision, but easy — easy to make, but tough to live with, like the decision to let your arm wither rather than see the bonebreaker. Nobody in Britain was allowed to switch from a tourist visa to refugee status. You had to decide before you crossed the border. Tourists had to leave after six months, but refugees might be able to stay forever. Jed and Laurie chose the line for refugees.

Finally their turn came. They were surprised when the immigration officer offered them a first-class train ticket to Belgium, hot lunch included.

“We want to stay in England,” Jed protested. “We’re not safe in Europe.”

“Any health problems?”

“No,” Laurie said. “We don’t need health care! We just want to stay safe.”

“Would you be interested in Berlin? I have a flight to Berlin leaving in an hour.”

“No,” Jed said. “We’re applying for asylum in the U.K. God save the king!”

“What about a tourist visa for three months, and you’ll come back and see?”

“No,” Laurie said. “We want asylum.”

“Are you wanted by the police in connection with a crime of any sort?”

“Of course not,” Jed said. “They let us go.”

“You’d be surprised,” the official said. “Lately it’s as if they finally realized it’s cheaper to let nonviolent offenders emigrate than to lock them up for life.”

“That would be funny,” Laurie said. “Like Castro letting the criminals go to Florida.”

“You’ll be in separate cells for weeks, then living in containers in a very bleak section of the country until we review your application. It can take years.”

“It’s like Hurricane Katrina,” Laurie said. “Americans are tough.”

“I like you,” the immigration official said. “I do. But you haven’t presented evidence of persecution, or even claimed it. Not feeling safe isn’t enough. Strictly speaking, feeling persecuted by one’s own emotions is a mental illness.”

Jed said, “They sent a friend of mine to prison for a year for trying to get a sick girl an operation. Now he’s a felon who can’t vote.”

“And you? What did they do to you?”

“I need asylum. Not a bunch of petitions from PEN and Amnesty International after I’m locked up.”

“They tried to keep us from leaving the country!” Laurie said.

“And here you are. Have you continued to publish your work?”

“Not in the past couple weeks,” Jed said. “We’ve been on the road.”

“Could you excuse me?” Laurie asked. “I have to go to the bathroom.”

She came back in a cloud of yeasty vagina smell with $2,000 in her front pocket. She sat on Jed’s lap. He palmed the money and shook the officer’s hand. Everybody smiled for the surveillance cameras. The officer signed his name on some forms and said, “Well, then, cheerio!”

They were official asylum applicants and free to go. While they looked for the train to London, Jed said it might have been cheaper if he’d been bold enough to whip out his wallet. He said he admired Laurie very much.

Laurie said, “Well, then, cheerio!”

They rode the Heathrow Express train without buying tickets. They told the conductor they were refugees, and he told them never to try that stunt again.

At Paddington they sat down on a bench, facing cupcake-size muffins that cost £4.50 each. “When I think of trying to live here on five hundred dollars, I think maybe we should have agreed to the containers,” Jed said.

“The north of England is the poor part,” Laurie said. “Poor places are cheap. We should go north.”

“Manchester,” Jed said, remembering the name and nothing else. They spent the night sitting next to a canal near Regent’s Park. It was very cold.

The next day they walked north. A woman working at a bakery gave them some bread as a present, and they ate it while continuing to walk. The weather got soggy. Late in the afternoon, the sole of one of Jed’s shoes started to flap around. “Why the fuck did I wear my interview shoes to become a refugee?” he asked.

“I could go into a variety store and steal a little bit of duct tape,” Laurie said.

“You smell too horrible to go anywhere indoors,” Jed said.

Through the open toe of his shoe, a burr was slowly working its way through his new tube sock. While he leaned on a guardrail to investigate, a passing car splashed his pants with greasy liquid from a puddle.

The whole trip north went like that, just one minor disaster after another. Laurie stepped in dog shit. Jed’s floppy shoe slipped into a pothole that had some kind of spiky thing in it. Laurie got caught stealing some cheese in a market and had to run away fast. The cheese turned out to be almost inedible, tasting of vinyl. When she cried, saying she was so hungry she was about to die, Jed offered her his “emergency granola bar.” They shared it, but she didn’t talk to him for two days.

They continued to walk. A hostel decided their fate. A handsome guy stood outside it, doing nothing, looking friendly. He called them over as they passed. He said they could take showers and spend the night on credit and apply for jobs in the morning. For the interview, he even lent Jed a pair of shoes.

The jobs were in a factory. From nine at night to two in the morning, Jed would shape dough by hand into artisanal pretzel shapes. From nine in the morning to two in the afternoon, Laurie would clean dough-making equipment. It was not enough money, but they could share a bunk.

Within a week, they realized that the hostel was attached to the factory and that all the employees were homeless refugees working illegally. The hostel was like the company store in the song “Sixteen Tons.” On their first day off, they hitchhiked back to London to get an address at a Mail Boxes Etc. so they could receive mail about their asylum applications.

Jed’s application was approved after seven months. Laurie’s was rejected. She was advised to return to the United States and enter Britain three months later with a different kind of visa that would entitle her to marry Jed.

He wasn’t sure he wanted to marry her. Their relationship had been ground down to almost nothing in the hostel. They were worn out from bunking with strangers who watched TV all night. To him she looked as lumpy as a pretzel, with dusty hair that didn’t belong. Her fingertips were thickly callused and when she touched him, he felt like flour. But she wanted desperately to get married. She knew their love would come back when they had real jobs and an apartment of their own.

Jed moved from the hostel to a group apartment for refugees in the East End of London, and Laurie flew to Detroit.

She stayed with friends who told her the news. She had not been in touch, but they were underwater on their mortgages, so they couldn’t go anywhere. Americans were easy to find.

All their journalist friends were still working as journalists, except for the guy in prison. They had switched to reporting on how taxpayer money was being wasted.

They wrote that the government should stop subsidizing (a) the oil industry, (e) weapons systems for export to dubious foreign regimes, (c) segregated private schools, (b) renewable energy, (f) foreign weapons systems we ought to be making ourselves with American technology, (d) public employees’ unions, and (g) ad nauseam. Taxes were down, but being wasted right and left. The story had long legs and could go anywhere, left or right. All the journalists were busy exposing waste, day and night. The newspapers were making money.

Laurie thought about the girl in Nigeria, who had never cost anybody a dime, unless you counted Jed and his friend who gave their careers. She wasn’t worth money to anyone, except maybe as kidneys and a liver. She needed to be fed and housed while she attended school, learning to be worth what Jed and his friend had paid.

Laurie was a little angry at Batula. She knew it was unjust.

She would have felt better if she had known that Batula’s arm was useless, and that she had become the eleventh wife of an old man with a street-food business frying chicken feet imported from North Carolina. No one knew Batula was sensitive and kind, with a quick understanding, an excellent memory for details, and kidney and liver damage from infections acquired during her first marriage, in the context of which her current liaison was adultery, punishable by lynching. Her mother was dead, and no one else had ever really known her. She had a low opinion of herself. Her husband had asked her not to talk when he was talking, and he talked nonstop, almost whenever he was awake, like a maniac. She was dependent on him, especially when she got sick. When he passed, his three sons would divide the property among themselves and put her out on the street. They were not good Muslims. They were total crap Muslims, the kind you read about.

In Laurie’s mind, Batula had been saved. She would receive asylum wherever she went, living in chaste freedom in women’s shelters, helping out in the kitchen until she learned to read and write and teach preschool or whatever short road self-actualization takes underprivileged girls down, and one happy day she would get married, truly married, at thirty, like a free woman, like Laurie.

After three months, Laurie returned to Britain with a visa that gave her permission to marry Jed. He wasn’t interested. They fought.

They stood on the close-mowed crabgrass between his ground-level room’s barred windows and a dirty canal. Potato-chip bags floated motionless in the water, mouth downward, like jellyfish. The fence encircling them was made of green plastic clothesline strung low between stakes, like a trip wire. Between them stood an ornamental pear tree that had died.

“Getting married would cost you literally nothing, and it would save my life,” Laurie said. “After everything we went through, and what I went through getting my visa and getting back here! This is incredibly shitty of you, Jed!”

“You didn’t go through that for me,” he said. “You did it for Donald fucking Trump and his shit-ass administration.”

“I what?”

“What I said! They made you get that visa, not me. We never planned on getting married. We wanted to work as journalists. That’s our life. That’s what they took away, not our failing relationship.”

“You can’t say that. You quit your job and made us leave the country! All our friends are still reporters!”

“Well, get this, sob sister. Their fake reporting is sad. When’s the last time you saw an article about a human rights violation?”

“That was your own mistake. Human rights aren’t real. They aren’t even an abstraction of something real. Power is real. That’s why people read your stories, to see power violate the weak. Fuck human rights, and fuck marrying you! I wouldn’t marry you for a million dollars!”

“I’d marry you for a million dollars. I’d take it and start my own magazine.”

“That’s such bullshit.”

It was, in fact, bullshit. He’d been fantasizing a lot lately about having been born rich. He liked to imagine that he had been born into a family where one set of grandparents had a ranch in the oaks near Carmel-by-the-Sea, and the other a lake of their own in the Adirondacks. His parents had been married in the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, and he was the sole heir to all of it, working behind the scenes in places like Davos to make the world more just and fair. He was way, way too loopy to start any kind of magazine, and the real reason he couldn’t marry Laurie was that he had lost his mind. Any sane man would have married her in a minute. She was beautiful and nice, and desperate to marry him. How could he fault that? There’s a time for ideals, and a time to act impulsively out of pragmatism.

“I’d do in-depth reportage about places like that bakery,” Jed said. “We were slaves there.”

Laurie turned away sadly. He had atrophied. She wished he were gone.

She didn’t mean to leave him forever, but he moved to different housing, and the next time she came by, his flatmates didn’t know where he was. He didn’t reply to her messages. She couldn’t find him without his help. She looked and looked for him. She loved him in reality, as a friend. He thought it was greed, but it was love.

She stayed in Britain as an illegal, with an unskilled job in an unlicensed retirement home. She remained a charming person, and an English accent made her even cuter than before. She volunteered with some NGOs and soon had a middle-class English fiancé. Jed was a moron to have blown her off.

In time he became a successful freelance journalist, reporting on human rights violations online, under a pseudonym, for free. He was simultaneously the kind of drunken bartender who says he’s a writer to impress girls. What he was depended on how you defined journalism. The difference was a matter of degree.