Archie Randolph Ammons, one of the great American poets of the twentieth century, never became as widely known as his contemporaries. He avoided reading his poems in public (“I get stage fright,” he wrote), and even when he received the National Book Award in 1993, anxiety precluded his appearing in person to collect it. I was one of the judges that year, and he asked me to read his acceptance speech at the ceremony. “As you’ll recall,” he wrote to me, “I show off but not up.” In spite of this intense emotional fragility, he wrote tirelessly.

If poetry is a perpetual standoff between tradition and the individual talent, Ammons always emphasized the latter. And unlike T. S. Eliot, whose allusive, multilingual poems established his individuality against the European canon, Ammons defined himself explicitly as an American poet writing of American places and American people. His goal, it seemed, was to reinvent lyric poetry for contemporary America.

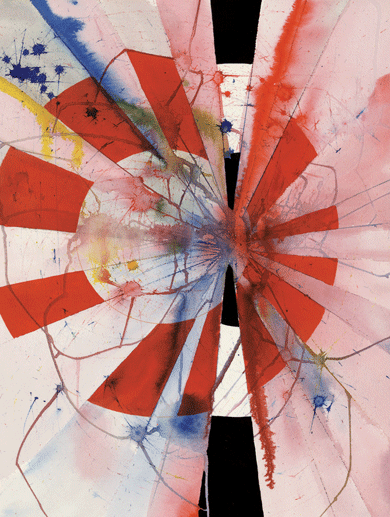

Ammons’s America stretched from the magma underneath the continent to the expanding universe above. He extended Walt Whitman’s generous conception of the country by incorporating into his work not only the vocabulary and the formulas of modern scientific discovery but also the revolution of the imagination that followed in its wake. In place of Whitman’s terrestrial, geographic idea of poetic structure, Ammons adopted a geometric one, drawing on forms such as crystals and spheres. With each new volume, he revealed a surprising phase of creative experimentation. He had the rare good luck of remaining a striking poet into old age, revealing in every decade fresh and original impressions on social, cultural, and personal phenomena.

Ammons’s America stretched from the magma underneath the continent to the expanding universe above. He extended Walt Whitman’s generous conception of the country by incorporating into his work not only the vocabulary and the formulas of modern scientific discovery but also the revolution of the imagination that followed in its wake. In place of Whitman’s terrestrial, geographic idea of poetic structure, Ammons adopted a geometric one, drawing on forms such as crystals and spheres. With each new volume, he revealed a surprising phase of creative experimentation. He had the rare good luck of remaining a striking poet into old age, revealing in every decade fresh and original impressions on social, cultural, and personal phenomena.

Ammons grew up poor.* His family lived near Whiteville, North Carolina, in a frame house that lacked both electricity (they had kerosene lamps) and indoor plumbing. They scraped by as subsistence farmers, raising pigs and chickens. Later, his parents attempted commercial tobacco farming, but they fell into debt and eventually sold the fifty-acre farm.

When Ammons was four, his little brother died of an allergic reaction to peanuts. The poet-to-be had a traumatic breakdown, which he recounted years later in the unforgettable elegy “Easter Morning”:

I have a life that did not become,

that turned aside and stopped,

astonished:

I hold it in me like a pregnancy or

as on my lap a child

not to grow or grow old but dwell onit is to his grave I most

frequently return and return

to ask what is wrong, what was

wrong, to see it all by

the light of a different necessity

but the grave will not heal

and the child,

stirring, must share my grave

with me, an old man having

gotten by on what was left

“To see it all by / the light of a different necessity” is a manifesto that accounts for Ammons’s persistent redefinition of the relation of poetry to life.

In his childhood home, Ammons once said, there were only three books: the family Bible and two others. There were also (who knows how) eleven pages of Robinson Crusoe, which, along with the sermons and hymns he encountered at the charismatic Pentecostal Fire-Baptized Holiness Church, helped to form his literary imagination. He was in the eighth grade when a teacher recognized his verbal gift and praised his first composition. He began to read voraciously in a wide range of subjects (the sciences, anthropology, ancient history, and, of course, poetry), a habit he maintained throughout his life. It was thanks to this reading that when, in his late teens, his dramatic Christianity failed him, Ammons quickly found a system he could credit intellectually — the inflexible laws of the universe, described in disciplines ranging from the bacteriological to the astronomical. The conflict between those lofty, inhuman laws and the phenomenal life of the body generated much of his poetry. As he wrote in 1970 to Harold Bloom, his first academic admirer, he was trying to pull off a “secularization of the imagination”:

The spiritual has been with us and will remain with us as long as we have a mind. . . . I don’t feel the desertion [Wallace] Stevens felt [when the gods disappeared], but how could I; I never felt the comfort he imagines before the desertion.

What Ammons had chiefly felt during his early exposure to religion was terror — the dread of hell and the fear of the Rapture.

After high school, Ammons worked in a shipyard in Wilmington; when World War II began, he enlisted in the Navy to avoid being drafted into the Army. He never saw combat, but as a yeoman, doing a clerical job, he was given access to a typewriter, a machine later indispensable to some of his poetic effects. During his service, Ammons kept a journal, amassed vocabulary lists, and studied materials from the Navy’s courses in speech and composition. Around night watches, he wrote his first poems — inept pieces in standard rhyme and meter, by turns sentimental and comic. More essential to him than these early attempts at verse were his awed shipboard observations of the interactions between land and sea. As he told The Paris Review in 1996:

The whole world changed as the result of an interior illumination: the water level was not what it was because of a single command by a higher power but because of an average result of a host of actions — runoff, wind currents, melting glaciers. I began to apprehend things in the dynamics of themselves — motions and bodies. . . . I was de-denominated.

The multiple separate actions absorbed into ocean swells and affecting the bordering shore tutored the young sailor in the vexed relation between multiplicity and unity, a theme that would preoccupy him throughout his career.

After the war, Ammons returned to the United States. The recent passage of the G.I. Bill enabled him to enroll at Wake Forest University, where he took English and premed classes and earned a B.Sc. in general sciences. Following graduation, he married his young Spanish teacher, Phyllis Plumbo; from his letters to her during their courtship we learn of the agony he felt trying to arrange his future so that he could support a family and still write. The couple went to Cape Hatteras, where Ammons taught (and acted as principal) at an elementary school. After a year, he decided to risk the uncertainty of a poet’s life, and started an M.A. program at the University of California, Berkeley. There, for the first time, he found encouragement for his work, from the poet Josephine Miles (although he silently chafed at her poetic taste). When he left Berkeley, his wife’s father offered him a job as a salesman in his scientific-glassware business in Millville, New Jersey; realizing that he and Phyllis could not live on his writing alone, Ammons accepted the position. Somewhat to his surprise, he became a successful sales manager, rising to executive vice president. He seems not to have been beset in that role by the anxiety that typically attended his self-presentation as a poet.

Despite the job, Ammons continued to write and to send poems to literary journals. They were almost uniformly rejected, and he grew so discouraged that in 1955, at the age of twenty-nine, he self-published a small book, Ommateum. In a letter to The Hudson Review, he explained that the volume’s perspectivism stemmed from his profound distrust of ideological prescriptiveness, whether religious or political. An ommateum is the compound eye of an insect, each facet of which, he wrote,

perceives a single ray of light, the whole number of facets calling up the image of reality. Each of the poems is to be a facet, of course, and the whole collection to call up the stippled outlines of the image of truth, truth, from the human point of view, as a growing thing, filling out.

Ommateum did not sell (the royalty for the first year was four four-cent stamps), and Ammons decided that he needed further instruction. The Chicago poet John Logan was offering a correspondence course in poetic composition, and Ammons sent him the book. He found an enthusiastic reader who understood his achievement: “I have read your book several times and I find it completely beautiful,” Logan wrote.

In 1961, Ammons attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where he met another poet, Milton Kessler. Through Kessler’s sponsorship, Ammons got his second book, Expressions of Sea Level (1964), accepted by the Ohio State University Press. On the basis of its aesthetic and critical success, Ammons was appointed to the faculty at Cornell University and moved to Ithaca, in upstate New York, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Around this time, Ammons recorded in his journal a crucial change in his idea of poetry, tracking his evolution from an overly intellectual writer into one who had come to respect feeling. This passage marks the watershed in his work between an “objective,” abstract, scientific language of thought and a more flexible language in which feeling — the larger entity summoned by experience — incorporates the intellect:

I wish I could put into words the coming-round I have experienced (intellectually) the last few years. I once despised feeling as worthless, evanescent, of no “eternal significance.” I thought only of the “permanent” outside, the revolving galaxies, the endless space, and man on his tiny speck seemed meaningless. Can I now make the shift to humanity? Can I feel again? Can my blood stir at last? I now see feeling as incorporating the intellect — I once thought them separate. Intellect is the slow analytic way — the unexperienced way to action: feeling is the immediate synthesis of all experience, intellect as well as emotion.

A decade later, in a 1971 letter to Harold Bloom, he put his creed somewhat differently. When he gave up the Neoplatonic One (a “saving absolute”) in favor of the Many (the vicissitudes of human life), existence took on luster, presence, significance:

I ran my motor fast much of my life seeking the saving absolute. There is no such item to be found. I had known these thoughts for a long time, and they meant very little, until I experienced them. I remember the hour I experienced them. Nothing changed, and yet everything changed. Grief, fear, love, life, death, everything goes on just as before, but now everything seems lifted, just a bit, into its own being.

But neither end of this continuum ever definitely won out. Ammons continued to vacillate between the One and the Many, a process manifested in his alternation between short and long poems. A volume of short lyrics — Briefings (1971), for example — was as characteristic of his aims as a book-length meditation such as Garbage (1993). The worry he felt about the long poems — into which he deliberately inserted as much manyness as possible — arose from the doubt that he could carry off such a degree of arbitrariness and multiplicity and still call the result a poem. Meanwhile, he fretted that the short poems could not represent the grand inclusivity of thought and language to which he aspired. And Ammons, who was musical, a fine pianist and singer, always worried about what sort of music the lines would convey.

Many vocabularies, scientific and psychological, remained active in Ammons’s poetry throughout his life, and he played constantly with possible attitudes toward nature, the body, marriage, loss, and death. In spite of its occasional awkwardness, Ommateum found a style, at once philosophical and colloquial, that allowed for appealing dialogues with items in nature — the indispensable sun, the poetic moon:

I went out to the sun

where it burned over a desert willow

and getting under the shade of the willow

I said

It’s very hot in this country

The sun said nothing so I said

The moon has been talking about

you

and he said

Well what is it this timeShe says it’s her own light

He threw his flames out so far

they almost scorched the top of the

willow

Well I said of course I don’t know

Comic diffidence before supreme forms of nature remained a part of Ammons’s later work, as did the truculence of the moon, here mutinously (if incorrectly) declaring her light to be her own. In his work, poetry — immemorially connected to the moon — exists side by side with solar nature, and claims its own inspiration.

Ammons never forsook the delights of the colloquial; his last book, Bosh and Flapdoodle (2005), like his first, makes ordinary speech a fundamental principle of style. Nonetheless, he was the first American poet for whom the discourse of the basic sciences was entirely natural. He had been saturated in it as an undergraduate at Wake Forest, and it had for him a moral intimation as well as an intellectual one: It spoke provable truth, and so became an object of alliance in his disaffection with Christianity. However, Expressions of Sea Level contains some rather unintegrated science-speak of aridity later to be disavowed:

honor the chemistries, platelets, hemo-

globin kinetics,

the light-sensitive iris, the enzy

mic intricacies

of control,the gastric transformations, seed

dissolved to acrid liquors, synthe

sized into

chirp, vitreous humor, knowledge

Besides their scientific inquiries, both Ommateum and Expressions of Sea Level contain poems of tender pathos, among them “Nelly Myers,” which commemorates a woman with an intellectual disability who lived with the Ammonses, and “Hardweed Path Going,” an elegy for Sparkle, the young Archie’s pet hog, slaughtered by his father. “She’s nothing but a hog, boy,” says the father as he holds the axe, but to the boy she is a friend, and her execution is horrifying:

Bleed out, Sparkle, the moon chilled

bleaches

of your body hanging upside-down

hardening through the mind and night

of the first freeze.

It was in his third book, Corsons Inlet (1965), that Ammons developed the two central tenets of his poetics: that life is motion, and that there can be no finality of expression, no absolute vision. Walking the Jersey Shore in the title poem, he realizes that he is not satisfied with “narrow orders, limited tightness,” but hopes to describe the “widening scope” of perception:

enjoying the freedom that

Scope eludes my grasp, that there is no

finality of vision,

that I have perceived nothing com-

pletely,

that tomorrow a new walk is a new

walk.

Various structural experiments occur on the page — the poet prolongs a single sentence into an entire poem (“Prodigal,” “The Misfit”) or, as in “Configurations,” turns to writing in columns:

The errant comma, the use of lowercase at the start of lines, and the absence of final punctuation recall E. E. Cummings; the careful downward progress of the words resembles the tentative steps of the cat in William Carlos Williams’s “Poem.” These lines directly contest the long Whitmanesque lines to which Ammons was intermittently attracted. And although both choices — short and long — offer freedom from ordinary lineation, Ammons was still not truly free. He continued to rely on such assertive conclusions as “I faced / piecemeal the sordid / reacceptance of the world,” the kind of conventional summing-up that his mature poetics would not permit. Such conclusive terminations are incompatible with the ever-anticipated “new walk” promised for tomorrow. The poet celebrates the casual tone of the placid “new walk” but has yet to accept, intellectually, that the outbreak of violent feeling is one of the indispensable and inevitable ingredients of his lyric world, confronting the pastoral of the seashore with a furious wind: “Song is a violence / of icicles and / windy trees,” “violence / brocades // the rocks,” “a / violence to make / that can destroy.” Acknowledging hostility in himself, and seeing an equivalent violence in nature, Ammons is preparing for the emotional explosions of his later poems.

In 1965, Ammons published Tape for the Turn of the Year, the first in a series of winter diaries. Convinced that a poem aspiring to true manyness must be cut off at a perfectly arbitrary place, he shaped his journal-poem to the narrow breadth and unforeseeable length of an adding-machine tape fed into his typewriter. At its most extreme, Ammons’s winter improvisation becomes a concrete poem:

*

***

*****

***

*clusters!

organizations!*****

*****

*****shapes!

)/(/(/)/)/)/(/(/)/(

designs!

Since Ammons saw forms visually, we can infer that these instances represent, first, a single module (*), repeated in self-mirroring triangular shape (and interrupted by an excited interpretation declaring such assembled forms to be “clusters!”). A rectangular form follows, composed of identical repetitions of the same module (preceded by a new triumphant announcement: “organizations!”). Then a more complicated and varying pattern of four ingredients is established (concave parenthesis, virgule, convex parenthesis, and underline), upon which the poet bursts out in sheer pleasure that he has at last seen “designs!” — a word implying a mind behind such configurations, as “clusters” and “organizations,” being biological forms, do not. From this example we may deduce the way in which Ammons views the accreting form of his poems: first an intelligible module in a recognizable shape; then a repetition of the same module in a new shape; then a more complex set of new modules, unintelligible at first glance but interpretable as a whimsical and intended design. His writings find equivalents for the abstract module-arragement in such traditional poetic shapes as alliteration (“clusters!”), anaphora (“organizations”), and quatrains (“designs!”).

In the winter of 1970, Ammons opened a new diary, Hibernaculum, with a Keatsian landscape (“I see a sleet-filled sky’s dry freeze”). Later, parodying Keats’s “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” the hibernating poet narrates his “studies” of a comically comprehensive world always assembling itself into design:

much have I studied, trashcanology, cheesespreadology,

laboratorydoorology, and become much enlightened and

dismayed: have, sad to some, come to care as much for a fluted trashcan as a fluted Roman column: flutes are

flutes and the matter is a mere sub-stance design takes

its shape in: take any subject, every-thing gathers up around it

Although Hibernaculum exhibits Ammons’s preferred end punctuation, the colon (which manifests the unbroken continuity of sentence-thoughts in a stream of consciousness), the poem still appears relatively conventional, with 112 stanzas, each containing nine broad lines laid out as three tercets, with the stanza breaks seemingly arbitrary. Without an artificial container, Ammons fears, shapelessness will overtake his poetic diaries. Toward the end of Hibernaculum, he mocks his own irrepressible inclusiveness:

if there is to be

no principle of inclusion, then, at least,

there ought . . .to be a principle of exclusion, for to go

with a maw atthe world as if to chew it up and spit

it out again as one’s own is to trifl e

with terribleaffairs: I think I will leave out China

In the Nineties, Ammons published two ambitious long poems, the single-sentence Garbage and the tragic Glare. They continued his pursuit of improvisation — a form of art, as he would have known, long accepted in music. About the eighty-page Garbage, he wrote:

I’ve gone over and over my shorter poems to try to get them right, but alternating with work on short poems, I have since the sixties also tried to get some kind of rightness into improvisations. The arrogance implied by getting something right the first time is incredible, but no matter how much an ice-skater practices, when she hits the ice it’s all a one-time event: there are falls, of course, but when it’s right, it seems to have been right itself.

Ammons is speaking here of the constant will-to-represent in the maker’s mind, urged by a command that seems to emanate from within the object itself rather than from “outside.” Of course, as the will to form evolves, so, too, do the creative results. The extraordinary geography of Ammons’s inner world changes as the reader moves through his work: There are hills and declivities, creeks and snowstorms, high altitudes and swamps. Whether the first impulse of the poet was technical (“a vague energy”) or intellectual (“an intense consideration”), it moved invariably toward a fusion of nature and sensibility:

Nature is not verbal. It is there. It comes first. I have found, though, that at times when I have felt charged with a vague energy or when I have moved into an intense consideration of what it means to be here, I sometimes by accident “see” a structure or relationship in nature that clarifies the energy, releases it. Things are visible ideas.

Although Ammons, with his compound eye, was one of America’s most original nature poets, we must not forget that a geometric “seeing” creates his templates. In “Figuring,” a strange essay published posthumously in 2004, Ammons makes the startling admission that a prior geometric element is present in everything he writes: “Since I ‘see’ what to say and then attempt to translate the seen into the said, and since every translation distorts, I thought I might try by figuring here to get close to the given mental images themselves.” “Mental images” follow, of which the first is a straight line going in a direction indicated by its final arrow:

This is flow, movement, motion. . . . The flow here is unidirectional, one-dimensional, unbounded: it is uncontested, unobstructed flow. It is motion “homogeneous,” meaningless. It is what the poetic line (except for special effect) should never be — loose, fluent, uninformed, unstructured.

This linear forward motion, without volume, is of course the basic motion of prose, “meaningless” in the realm of lyric.

After the repudiated figure of the advancing straight line, Ammons offers a succession of fascinating geometric alternatives, all directed against conclusiveness: “The poem, if it is to stop, must carry heterogeneity all the way to contradiction.” His penultimate geometric shape, too complex to reproduce here, is a double-shelved sphere with five named radii, providing Ammons with his ultimate belief and reassurance:

If the earth, the mind, and the poem share a common configuration and common processes within that configuration, then it ought to be possible for us to feel at home here.

The lyric theory in “Figuring” will in time modify critical discussions that until now have fastened chiefly on the immediately appealing thematic dimensions of Ammons’s poems — emotional, philosophical, and epistemological. The dilatory “progress” of the long poems can seem exasperating until one recalls the active geometry of utterance subtending the author’s words; one knows that he wishes, at all costs, to avoid complacency, conclusiveness, and conclusion. Weather, as he realized, is his perfect aesthetic counterpart: It cannot be arrested, never repeats itself exactly, and remains unpredictable in its changes. But underneath the formal geometry, underneath the symbolic correspondences, lie the strata of personal suffering that the poet must understand and, for his art, transform. Poetry, Ammons wrote in a 1989 essay, moves

the feelings of marginality, of frustration, of envy, hatred, anger into verbal representations that are formal, structuring, sharable, revealing, releasing, social, artful. . . . Poetry dances in neglect, waste, terror, hopelessness — wherever it is hard to come by.

Every reader of Ammons will recognize the dance of geometry among emotions.

At one time, I had thought that by reading all of Ammons, from the epigrammatic Briefings and the shapely lyrics of A Coast of Trees (1981) through the “epic” meditations (embodying “minor forms within larger motions”), I had seen all his qualities. Then, four years after Ammons’s death, Bosh and Flapdoodle was published. Though he composed it in the late Nineties, Ammons chose not to release it during his lifetime. By retaining his last book, he kept his poetry alive, cryopreserved, so that he would not be dead as a poet while still living in the flesh. Reading his final volume, I felt so disconcerted that for some time I could not find a way to write about it. Its subject is death, faced directly and dismissively: “Fall fell: so that’s it for the leaf poetry.”

Bosh and Flapdoodle is the most transparent of Ammons’s books. Although it seems airy on the page because of its couplet-stanzas, it is generated by a bizarre poetics in which pathos is bathos and vice versa, all often confined to an arrantly simple diction. “Why?” I asked when I read it. I can answer only by giving a sample, which sees the poet in old age recalling an interview with a cheery hospital nutritionist. With barefaced inclusiveness, Ammons names the poem “America,” since everyone in the country is dieting and backsliding, fasting and slipping.

Eat anything: but hardly any: calories are

calories: olive oil, chocolate, nuts, raisins—but don’t be deceived about carbohydrates

and fruits: eat enough and they will make youas slick as butter (or really excellent cheese,

say, parmesan, how delightful): but you mayeat as much of nothing as you please, believe

me: iceberg lettuce, celery stalks, sugarlessbran (watch carrots, they quickly turn to

sugar): you cannot get away with anything:eat it and it is in you: so don’t eat it: &

don’t think you can eat it and wear it offrunning or climbing: refuse the peanut butter

and sunflower butter and you can sit on yourbutt all day and lose weight: down a few

ounces of heavyweight ice cream andsweat your balls (if pertaining) off for hrs

to no, I say, no avail: so, eat lots ofnothing but little of anything: an occasional

piece of chocolate-chocolate cake will be allright, why worry

The preposterousness of dieting when one is dying (or nearly so) suits Ammons’s gift for delightful social satire. But by including himself with the rest of us, he writes a humane satire, not a scornful one.

Ammons’s final aesthetic aim, as he states outright in Bosh and Flapdoodle, is to say the most with the fewest words: This sparse poetry, which he wryly called “prosetry,” can express the hellish as well as the comic. The rage and frustration that were so constitutive of Ammons’s earlier years never vanished; they were in fact the fire from which the poems erupted, poems that warmed readers while consuming the author. He reproaches himself, saying:

did I take my bristled nest of humiliations

to heart: what kind of dunce keeps a firegoing like this: what do people mean coming

to hell to warm themselves: well, it iswarm

Yes, the troubled hell of Ammons’s poetry is warm, but it has innumerable other qualities as well: sympathy, anger, love, irritability, patriotism, sadness, humor, risk — and, most of all, original perceptions, rhythms, and cadences. “In View of the Fact,” one of the most touching poems in Bosh and Flapdoodle, turns the Ammonses’ address book into a paradigm for the poet’s work. Everyone, it seems, lives life pell-mell, with circumstances that change as friends marry, have children, move away, or die:

The people of my time are passing away: . . .

it was once weddings that came so thick and

fast, and then, first babies, such a hullabaloo:now, it’s this that and the other and somebody

else gone or on the brink: . . .our

address books for so long a slow scramble now

are palimpsests, scribbles and scratches: ourindex cards for Christmases, birthdays,

Halloweens drop clean away into sympathies

Ammons’s poems, from the first to the last, are a record of American life, speech, and imagination in the twentieth century, a master inventory of the vicissitudes of human existence, worked by genius into memorable shapes.